Lou Pecora began his career in the VFX more than 17 years ago. He joined Digital Domain in 2000. He worked on projects such as I, ROBOT, PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: AT WORLD’S END, TRANSFORMERS: REVENGE OF THE FALLEN or IRON MAN 3.

Note: Nikos Kalaitzidis (DFX Supervisor), Jonathan Green and Dan Brimer (VFX Producer) have contributed to this interview.

What is your background?

I have a compositing background. I started out doing morphs in Elastic Reality in the 90’s on TVs BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER and ANGEL at Digital Magic. Then I came to Digital Domain and started doing some comp work. It really hooked me and I just kept going with it. I ended up becoming a Comp Lead and then a Comp Supervisor for quite a few years before getting the chance to VFX supervisor some bits and pieces on other shows. This was my first big show as a VFX Supervisor.

How did you got involved on this show?

I got involved with the show due to some prior relationships with the studio and other key people on the show.

How was the collaboration with director Bryan Singer?

Given that Bryan created this series of films and has a distinct passion for the stories and visuals associated with them, it was very clear that he had a well-thought-out vision of what the work should look and feel like. This came across from the very beginning.

We tuned in to that very quickly and easily and it just went from there. I feel like we didn’t waste his or Production VFX Supervisor Richard Stammer’s time with iterations that we weren’t confident about. In doing so, it made for a very easy collaboration. In the end, I feel that X-Men: DOFP turned out exactly as it was initially explained to us in turnovers. Bryan’s clear vision and direction didn’t waiver or change tracks during the process. That consistency was really great and allowed us to use our time honing, refining, and polishing the work instead of iterating in circles.

What was his approach about the visual effects?

He was very clear about making sure that the visuals be both stunning and immersive, but also not distracting from the story or the performances of the actors and actresses. This cast is absolutely incredible and there was no way any of us was going to distract from their performances. The directive was clear that the VFX support the story and walk that fine line of being epic, but not distracting. That sounds contradictory, but once we hit the groove it was very easy to predict when something was going to call too much attention to itself. We would then pull back on the offending effect before submitting it to him. It seemed to work beautifully as we got very few surprises in notes from Bryan.

How did you work with Production VFX Supervisor Richard Stammers?

Richard was absolutely fantastic to work with. His direction was always very clear and articulate, and his demeanour is very pleasant and fun. One can really feel the passion and experience he brings to the work. We did most of our reviews by way of cineSync, but as we got near the end of the show, emails, quick phone calls, and even texts would go back and forth at all hours of the day and night to make sure that notes got to us in the most timely fashion.

What are the sequences done by Digital Domain?

Digital Domain was responsible for approximately 430 shots – roughly a third of the show’s VFX work. We were responsible for all of the Mystique transformations and a fully CG environment for the 1973 RFK stadium, White House, and White House grounds. The environments included structures, some set dressing, skies, and trees. We created a pristine environment and a dynamic destroying/destroyed version of each environment, plus all the accompanying FX, such as smoke, dust, debris, atmospherics, etc.

In a particularly challenging set of shots within one of our sequences, we had the task of pulling President Nixon’s underground bunker out through the front of the White House, thus destroying the entire southern face of the structure.

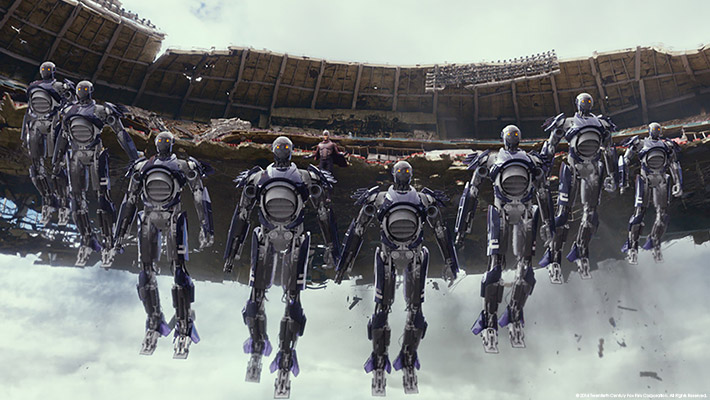

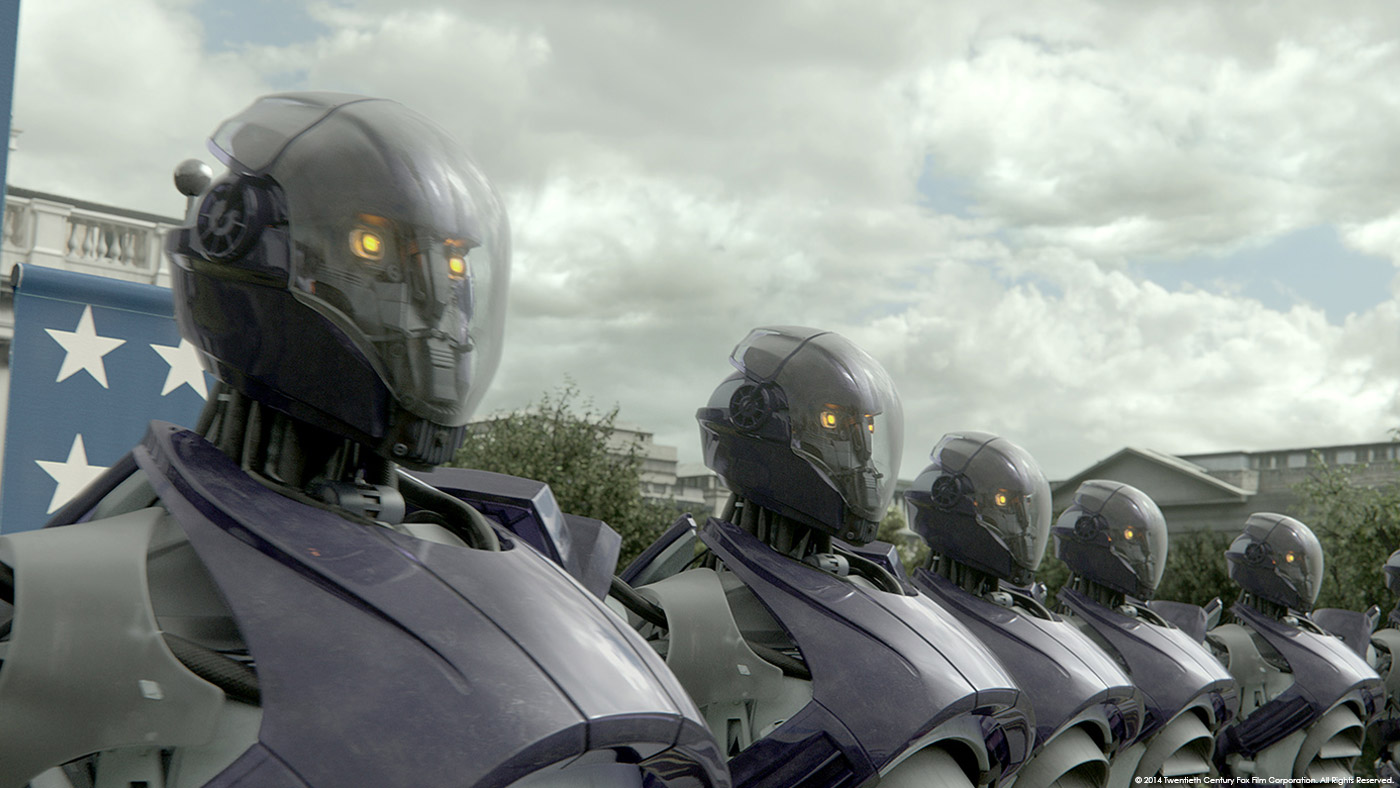

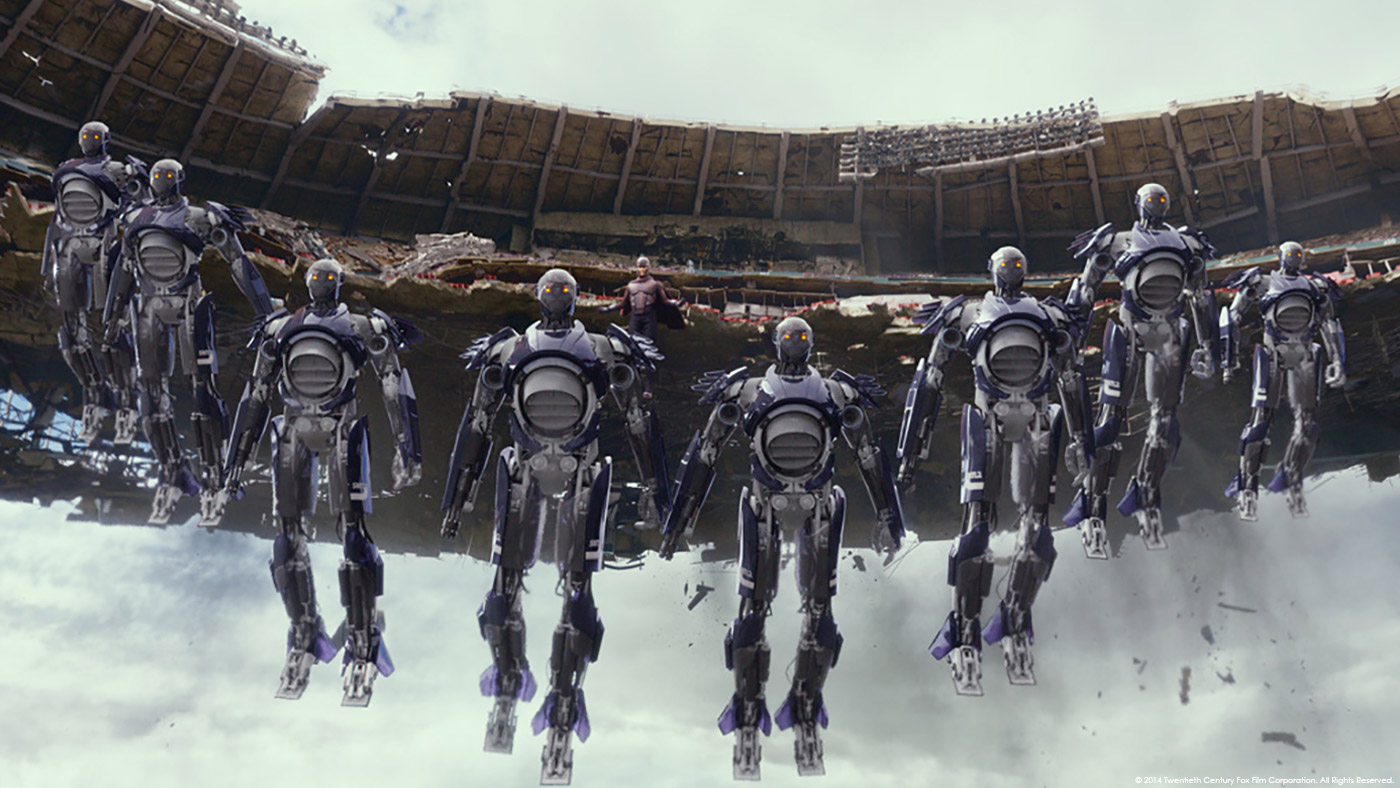

Digital Domain was also responsible for creating all of the vintage 1970’s Sentinel robots and their associated thrusters, exhaust, weapons, tracers fire, and ground impacts.

Additionally, we contributed heavily to a sequence of Mystique escaping from a Paris hotel. The sequence included a cool slow motion shot that follows a bullet from the gun, out the window, and right into Mystique’s leg. That sequence also required us to create a period Paris set extension.

There was a smattering of other challenges – like the taser wires that Striker uses on Mystique in the Paris hotel, some set extensions in Saigon and on the Potomac, numerous CG Mystique eye replacements, seamlessly blending Mystique’s on-set body stocking with her real skin, the fountain statues that Magneto uses to restrain Beast temporarily, and the vintage Sentinel-vision.

How did you approach the Mystique’s transformations?

We wanted to approach this from a physically possible standpoint. By that I mean that we wanted the mechanisms involved in the transformation to have some basis in reality.

I know that sounds crazy, so let me elaborate! We started with the concept of a deck of cards flipping over – something we have all seen and understand how it works. The idea is that on one side of the card is one character involved in the transformation and on the flip side is the other character. Then, the rig allows us to define the leading edge and trailing edge of the card flip very precisely. Any time Mystique would change to more than 2 characters there would obviously have to be a dissolve happening someplace, so we chose to have that happen off-screen on the side of the feather that is not visible at the time.

The reasons for going through all of this extra trouble was to avoid a wipe, as much as possible. We just didn’t want the effect to look like a wipe.

Can you tell us more about its rigging?

Mystique’s Rigging Developer, David Corral, built a real-time rig in Maya which was used to scale and animate the flipping of the feathers throughout the transformation process. The rigs had to be incredibly flexible, since we knew from early on that – depending upon Mystique’s distance from camera or how fine the details were on the part of the body that was changing – we would have to scale the feathers up or down and vary the speed of the actual flipping animation, as well as the specific leading and trailing edges of the transition zone. Furthermore, we wanted some variation to these feather sizes, so that had to be built into the rig, as well, to give the animator enough latitude to art direct the transformation.

Can you explain in details about the recreation of Paris for the Mystique Escape sequence?

We used some photographic reference from the 1970s to make sure that we kept everything looking vintage and period correct.

Environments Supervisor Jon Green then built geometry for the structures and projected paintings onto them. The Paris sequence was all shot in Montreal, and although the architecture could pass as European, it was missing the mansard rooftops that are so distinctive to Paris. So rather than completely replacing everything that was filmed, we developed some of these Parisian-style rooftops in 3D and added them on top of the foreground buildings. Beyond those foreground buildings, we built an expansive 3D matte painting based on photography taken from various locations around Paris.

How did you created the Vietnam Army Base environment?

There was a small set built for the Vietnam Army Base on a remote airstrip that we needed to extend to make it feel far more substantial. Unfortunately, there was no reference photography captured of this set, so the environment required extensive 3D development. We were able to gather some texture details from other plates in the sequence, but the added vehicles, helicopters, trees, and miscellaneous army base dressing all required look development. We used SpeedTree to create the animated palm trees, as well as the bamboo and smaller palm shrubs. Once we had a structured layout of the Army base, everything was rendered using V-Ray. Along with the animated palms, there are blowing flags and a jeep driving through the environment to provide the set with life.

Can you tell us more about the design and the creation for the Sentinels?

Our role in Sentinel creation started with matching the practical Sentinel built by Legacy Effects. We used that as a starting point and then added dust, radial scratches, etc to ‘dirty up’ the robots. As the sequence goes on and the Sentinels get more and more time in action, there are more and more scratches, dirt, dust, etc on them – especially the ones that see some battle!

How did you handle their rigging and lighting?

Rigging Lead Hans Heymans put a lot of really nice procedural controls in the rig – everything from vent shake to hose jiggle – and it allowed animators a lot more flexibility to focus on the overall movement of the Sentinels and let the secondary animations mostly take care of themselves. Of course, there were scaling controls to allow for more or less overall secondary movement, but for the most part animators could set these to defaults and it would work.

For the lighting, Lighting Lead Tim Nassauer was responsible for doing the look development on the Sentinels and incorporating Senior Texture Artist Chris Nichols’s detailed texture work. Tim had a lot of great ideas he put into the Sentinel look dev – things like the radial scratches or swirl marks that would come from polishing or wiping down the plastic surfaces. He added controls to amp up or reduce down the level of dirt and grunge on the Sentinels, based on how large in frame they appeared. This allowed us to maintain a consistent look for the robots.

Can you tell us more about their animation?

Animation Director Phil Cramer led our animation team. We discussed some overall concepts and rules for how we would approach the animation, and then he and his team ran with it. We came up with a strategy to deal with the size vs agility ratio we would have to straddle in order to make the Sentinels feel big and somewhat bulky but never clumsy or clunky. One of the guidelines we subscribed to was to keep the action fast in close ups to accentuate the agility and slow it down for the wide shots, in order to maintain the scale and weight.

How did you design and created the Sentinels vision?

Nick Lloyd, Digital Domain’s Art Director, came up with a bunch of initial concepts. Taking Bryan’s feedback on these concepts, we animated the text, the DNA helix, and the associated graphics to try to capture the feel of old computers and oscilloscopes. I am somewhat of a vintage computer and video game aficionado, so I spent some time with my old Atari computers to get a feel for the cadence of text scrolling and such, in order to give the Sentinel vision a period look. I also studied other vintage computers and game systems to get a feel for screen refresh rates, hum, etc. and incorporated all of that in there.

How did you created the Washington DC environment?

Environment Supervisor Krista McLean was in charge of our Washington DC environments team. We used a lot of period reference and even called the White House historian to get details about which trees were there and how big they were at the time.

We all realized early in production that the demand for a large quantity of CG foliage was required to have the White House South Lawn come alive. SpeedTree was used to create each asset. However, in order to integrate this vast array of complex green assets into Digital Domain’s pipeline, we had to write a custom application to aid in the process. For the show, we built a workflow to bridge SpeedTree with our Maya and V-Ray pipeline and dubbed it ‘SpeedBridge’. SpeedBridge allowed the Environments team to easily integrate the SpeedTree generated files (both models and animation) into the larger DD pipeline. Both a stand-alone and a Maya integrated solution were developed. SpeedBridge inside Maya allowed the textures and subsequent V-Ray materials to publish with the tree asset as a whole. This application also made it much easier to update both animation caches and models. The ease of use made it possible to generate a vast number of species – and variations of these species – at a pace that would otherwise not have been possible.

In the end, approximately 400 individual trees and bushes were meticulously laid out on the White House grounds. Approximately 200 of them had low, med, and high wind variations. The trees were incredibly heavy; we hit a poly count of up to 2.2 million on some of our Red Oaks and other really dense leafy trees. The only way we were able to view the trees in Maya was by using V-Ray’s low-res vrmesh format.

We had to revise nearly all of the tree models, in order to generate a broken, flattened, or somewhat destroyed version for the post-stadium landing environment. Krista and her DC Environments team had certainly earned their green thumbs!

We also modeled and textured the White House, the Washington Monument, and the buildings surrounding the While House. On the South Lawn, we even added a working fountain with a water simulation.

Can you explain in details about the RFK Stadium creation?

At first, we had our on-set supervisor Jesse James Chisholm and on-set environments capture technician Viki Chan go to the actual RFK stadium and photograph every angle and corner of the stadium. RFK was also recorded by extensive Lidar and an aerial unit to guide the modelers.

Knowing that this asset would be heavy to render as a detailed baseball stadium with over 65,000 seats, we designed it by quadrants, like slices of a pie. This way, if we needed to render out a small part of the stadium for a shot, we could economize the render by only using a few slices of the pie. Trevor Wide, our texture lead, used Mari to supply textures and materials to our stadium lookdev lead, Alex Millet, who would create his final renders via V-Ray. We would pass the lighting renders to our Enviro team to paint and project additional details, as seen through the camera. After the stadium was dropped on the White House lawn, the Enviro team created Digital Matte Paintings (DMP) to project back onto the Stadium to emphasize the destruction caused by Magneto.

How did you manage the destruction of the RFK Stadium?

A rough Maya-based animation was created for the timing of the liftoff and included some of the major features of the stadium (like the roof) bending in specific areas. That animation was brought into Houdini and would drive the overall simulation. DD’s senior FX Artist Daniel Stern took ownership of developing the simulations that would be used for the liftoff and dropping of the stadium. For this, we used our in-house rigid body system, DROP, which we initially developed for the disaster film 2012. Using this system, pieces of the stadium model broke or tore depending on the pressure that the driving animation put onto them. The artist was able to mark areas which were not supposed to break. After the first simulation step was approved, it was fed into a second, higher detailed one. Particles and layers of dust were then added onto the result.

The stadium’s 65,000 seats reacted (by flapping up and down) based on their rigid body simulations. To transfer the geometry for them over into V-Ray, we used the same technique DD earlier utilized to get millions of spaceships animated and rendered for ENDER’S GAME. Each rigidly moving piece was exported as an aligned point and connected to its high-res representation at render time.

Magneto took out the White House bunker. Can you explain in details about your work on it?

That bunker was a lot of fun. I would have to say one of the most complex shots we did was the initial break out of the bunker as it flies out of the White House straight at camera. Because pieces were dynamically layered – that is, sometimes a piece was in front of something and it ended up behind it later in the shot – we had to run the whole thing together. There were many aspects to this: trees, White House walls & columns, simulations of the broken White House debris, miscellaneous debris like internal furnishings, the bunker itself, and all of the associated dust & smoke. It was a beast to render, so we only got a couple of cracks at it.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

Creating so many unique simulations that haven’t been seen before. By getting people together that had various experiences, unique insights on differing approaches, and a mass of creativity, we came up with some very stunning methods that we could all ultimately visualize.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

I definitely didn’t get a lot of sleep during this one! There was just so much work to do that I feel like we were running full tilt for the entire duration of the show! Exhausting to say the least, but very fun at the same time. The team really got along well and we kept our sense of humor up, which was really the only way we had a chance to make it, in my opinion!

What do you keep from this experience?

The most precious things I will keep from this experience are some of the relationships I made with people during the process. Watching people take on challenges that they were initially unsure they were ready for, then to see their confidence grow as they met challenge after challenge, was so rewarding for me.

Seeing this in other people reminds me to keep that same spirit in myself when faced with a challenge that I think I might not be ready for.

How long have you worked on this film?

8 months.

How many shots have you done?

430 shots.

What was the size of your team?

All told, 242 people were on the show at one time or another during the course of the project, plus a lot of support people from DD’s Los Angeles and Vancouver facilities.

What is your next project?

Not allowed to say, but it is a fun one!

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD

THE TERMINATOR

ALIEN

STAR WARS

Many more have joined the ranks of these over the years, of course, but these were the ones that got me when I was a kid and early teenager and really captured my imagination. Ray Harryhausen’s work in particular really left an impression on me as a kid. I remember the sense of awe I felt when I first saw those movies.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Digital Domain: Dedicated page about X-MEN: DAYS OF FUTURE PAST on Digital Domain website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2014