Mark Spatny has been working in visual effects for over 25 years as a VFX Supervisor and Producer! He has worked on a number of shows including Armageddon, What Dreams May Come, Heroes and Runaways.

What is your background?

My degree is in lighting and set design for live theater, and I did that for 10 years before moving into computer graphics as a profession. It’s been a huge help to my career in VFX, because I’m always approaching VFX elements with the goal of matching both the production designer and cinematographer’s vision, being able to communicate with them in their own language, as well as understanding their design challenges and the reasons for the choices they make. I think that’s critical for having a unified design between the practical and CG elements.

How did you get involved on this series?

Jay Worth (who is both a producer and a VFX supervisor on The Peripheral) and I have known each other since the mid-2000s, when we were both panelists on a San Diego Comic Con panel about visual effects. In early 2021, Jay was supervising multiple shows for Kilter Films simultaneously, so he needed a partner on The Peripheral who could handle both the VFX producing but also split the VFX supervising tasks. He reached out to me because there aren’t a lot of people with the experience in both roles that I have and can switch back and forth fluidly between them. I jumped at the chance to work with Jay because I’m a big fan of his.

How was your collaboration with the showrunners and the directors?

It was great. We had several months of prep before shooting to work out many of the creative challenges for the show with the directors and showrunners, and in post the executive producers made themselves available for us whenever we had questions or needed feedback or approval of work in progress. It was a fantastically collaborative project, with all sides bringing ideas to the table throughout the post process to take everything to the highest possible production value.

What was their approach and expectations about the visual effects?

Jonah Nolan very much prefers to get as much work in camera as possible, and to use CG augmentation sparingly, when something can’t be done practically. For that reason, several big scenes that most TV shows would have shot on a green screen were shot on an LED volume, with our team providing backgrounds to play on the screen. For example, all our London driving was shot on the Arri LED Volume in London, using backgrounds that were shot on London streets with a 9-camera circle rig. We stitched those plates together into 360-degree video that was 12,000 pixels wide for playing on the volume.

Similarly, for a scene in a glass elevator passing through impossibly large scientific laboratories, Rodeo FX in Montreal provided 360-degree animated plates to play back on the volume. This was critical for getting all the proper reflections on chrome, glass, and white surfaces on the set and on the actors.

But most importantly, the visual effects needed to make it very clear that the world of Clanton, North Carolina in 2032, and London in 2099, looked and felt very different.

How did you organize the work with VFX Supervisor Jay Worth?

Jay functioned as the creative lead, setting the broad strokes for all the looks with our directors and executive producers. Then together, we filled in the details. In dailies and on creative calls with our partner companies, we reviewed shots together and agreed upon the changes and refinements we would ask for. Jay led the discussions with our directors and EPs because of his long-standing relationship with them, while I was the primary contact with our on-set teams and post VFX partners. In most cases, I made the choice of which shots were assigned to which VFX company. I also worked most closely with our editors to work out temp effects and timings for shots and did any necessary concept art or mockups for our vendors.

How did you choose the vendors and split the work amongst them?

Ultimately, we had about a dozen VFX companies working with us. BlueBolt in London was our primary creative partner and provided all the on-set supervision in London. They did about 1/3 of the work on the show. Since their area of specialty is in environment work, we focused their assignments on that. They also did all the LIDAR scanning of our sets and props. Like any other show, we assigned the rest of the work based on prior relationships, and what sequences the individual companies thought they could best handle, based on their current staffing. Crafty Apes did all the shots of our triple amputee character Conner and most of our action enhancements like blood and muzzle flashes. Refuge did all of our CG robotic enhancements. Zoic, beloFX, and Rodeo handled some of our other more difficult CG challenges. I specifically reached out to Zoic because I’ve known the owners for over 20 years. And although I had never worked with them before as a client, I knew their artists can deliver amazing work on TV schedules. Other companies were picked because of work either Jay or I had done with them previously.

London is playing a huge part in the series. Can you elaborate about its futuristic design?

There are two major considerations that drove the look of future London. First, 90% of the earth’s population died in the series of catastrophes known as the ‘Jackpot, with the survivors being mostly among the ultra-rich who had the resources to survive. So, unlike most visions of the future, there was no need to show that massive construction of new buildings happened in the years between now and 2099. The few survivors are living and working in the buildings that survived.

Secondly, we eventually learn that most of what we see of London is really an Augmented Reality representation of a nostalgic, idealized version of London, hiding the decay caused by most of London being abandoned during the Jackpot.

Both of these things pretty much allowed us to play contemporary London as future London, with a few elements of futurism added, like the glass solar panel streets and the mile-high air scrubbers.

How did you create the massive structures amongst London?

The giant air scrubbers are enormous air purifiers, removing pollution and residual radiation from the air to make London more habitable. We went through many design ideas driven by the art department, starting with the idea that they were a bio-mechanical hybrid using both industrial filters and trees or algae to filter out the pollution.

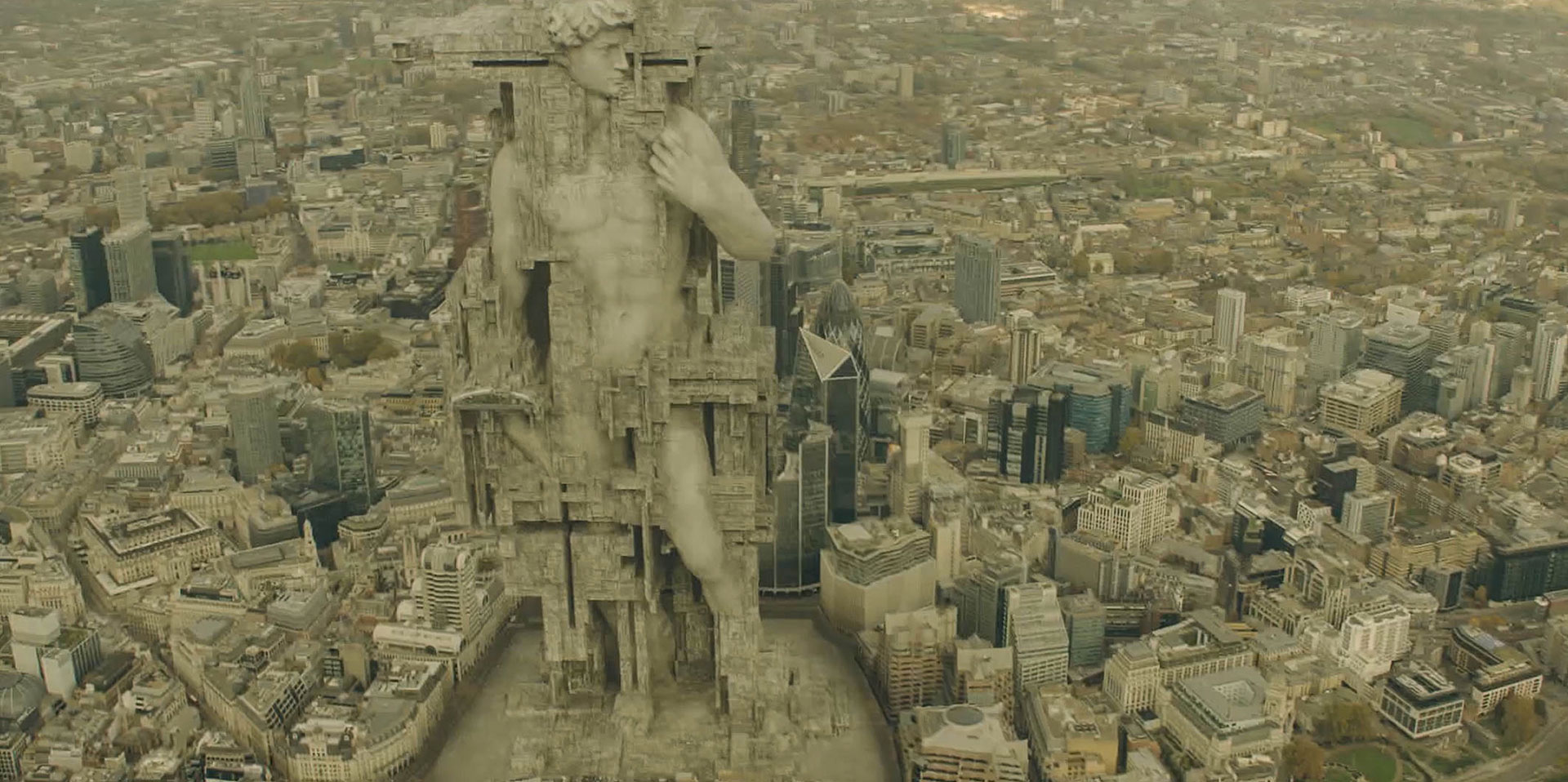

Eventually, though, our producers gravitated to an early concept design featuring Michelangelo’s ‘David’ that did away with the organic elements, and instead envisioned them as giant civic works of art that also cleaned the air. We bounced ideas around about what those works of art might be, such as representations of traditional British mythological characters like King Arthur or scientists like Isaac Newton, but eventually the producers felt classical Greek and Roman statuary would be a better match for our vision of London.

These were then modeled by BlueBolt in Maya and tracked to footage of the city. They radiate in two concentric circles around London, kind of like Stonehenge, with David being the center of the two circles. We did three days of helicopter shoots for the aerial footage featuring them.

Also, (and to be fair this was never part of the discussion with our producers, it’s a personal observation), but the British have taken a lot of heat for appropriating important historical objects during its colonial period. For example, the Rosetta Stone. So, I personally thought it was interesting to suggest that England was still doing that in the future instead of making giant works of art featuring their own cultural history.

Which location was the most complicated to create?

That would be the augmented reality ‘Jackpot Museum’ in the graveyard that we see in episode 4. We started working on that before the scene was even shot, as previz, and it was among the last sequences we finished for the show. Since it was imagined as a museum, each beat of the story of the fall of humanity had to be conceived as a unique work of art that had to be designed with its own look. We tell the story of failing power grids, plague, environmental collapse, and nuclear terrorism. All via motion graphics created by Kontrol Media in Belgium. Thankfully, our director Vincenzo Natali had a very strong vision of what those works of art should be, and his storyboards drove our designs.

How did you handle the challenge with the reflective London roads?

Honestly, that was pretty much brute force paint and rotoscoping. Removing the painted traffic lines, as well as most of the people and cars on the road, with faked reflections tracked in from the sky and the surrounding buildings to create the glass look. BlueBolt set the look of the glass streets, but the bulk of those shots were done by Bot in India.

Also, it might not be obvious, but the chevrons that light up in front of the vehicles as they travel were conceived of as a safety feature. They show the stopping distance for the vehicle, to alert pedestrians whether the car can stop in time if they cross the street. If you look carefully, you’ll see that the distance of the chevrons from the vehicles changes as they slow down or speed up.

What was your approach with the robots?

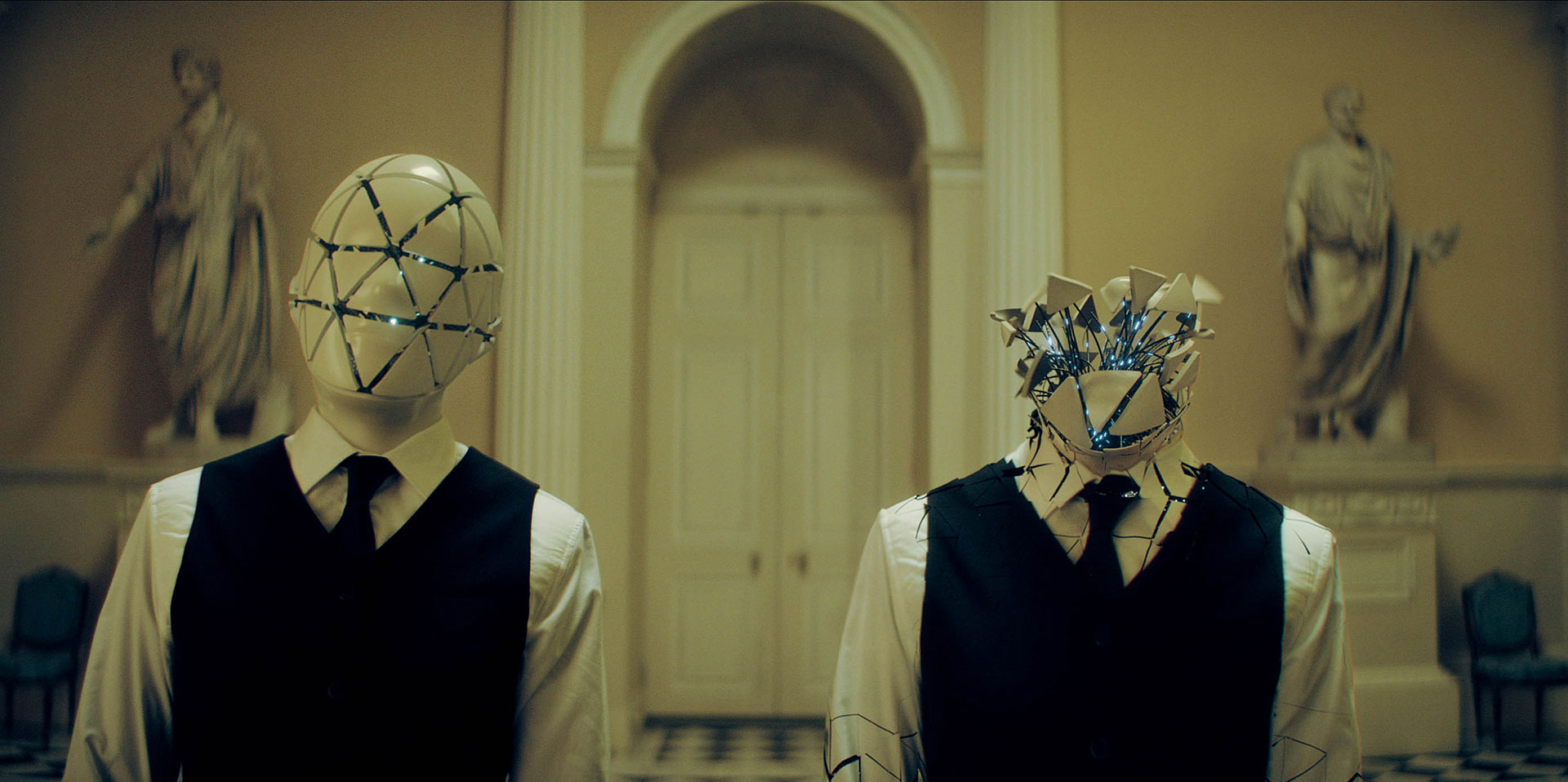

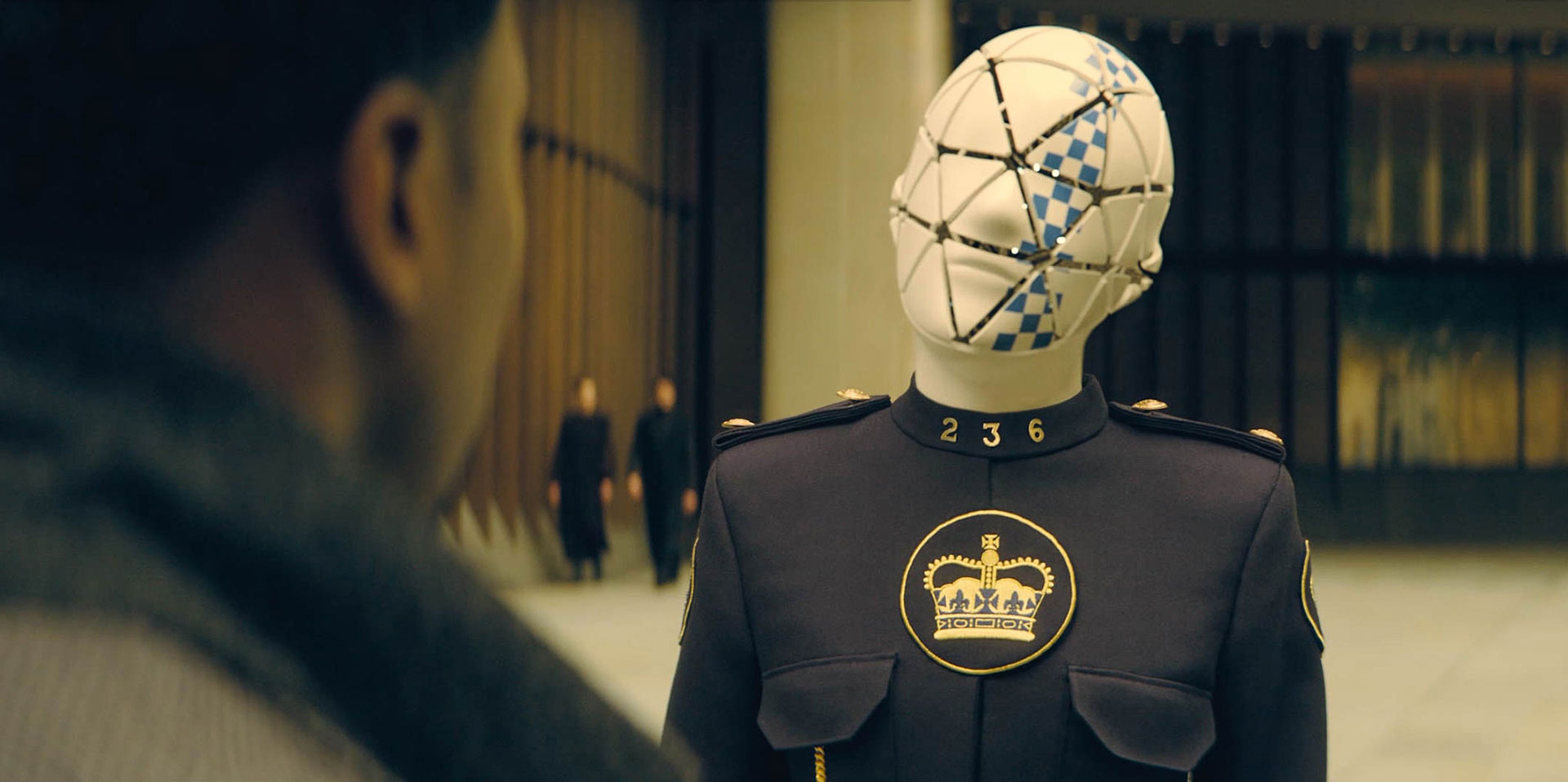

Our robots (called ‘Koids’ in the show) were originally meant to play practical, as actors wearing masks. But in post we realized that they didn’t have the futurism we were looking for. We first experimented with using 2D comp tricks to make their heads or necks out of proportion to their bodies, so they looked less human. But ultimately, we decided that CG head replacement was the answer.

Can you explain in detail about their creation?

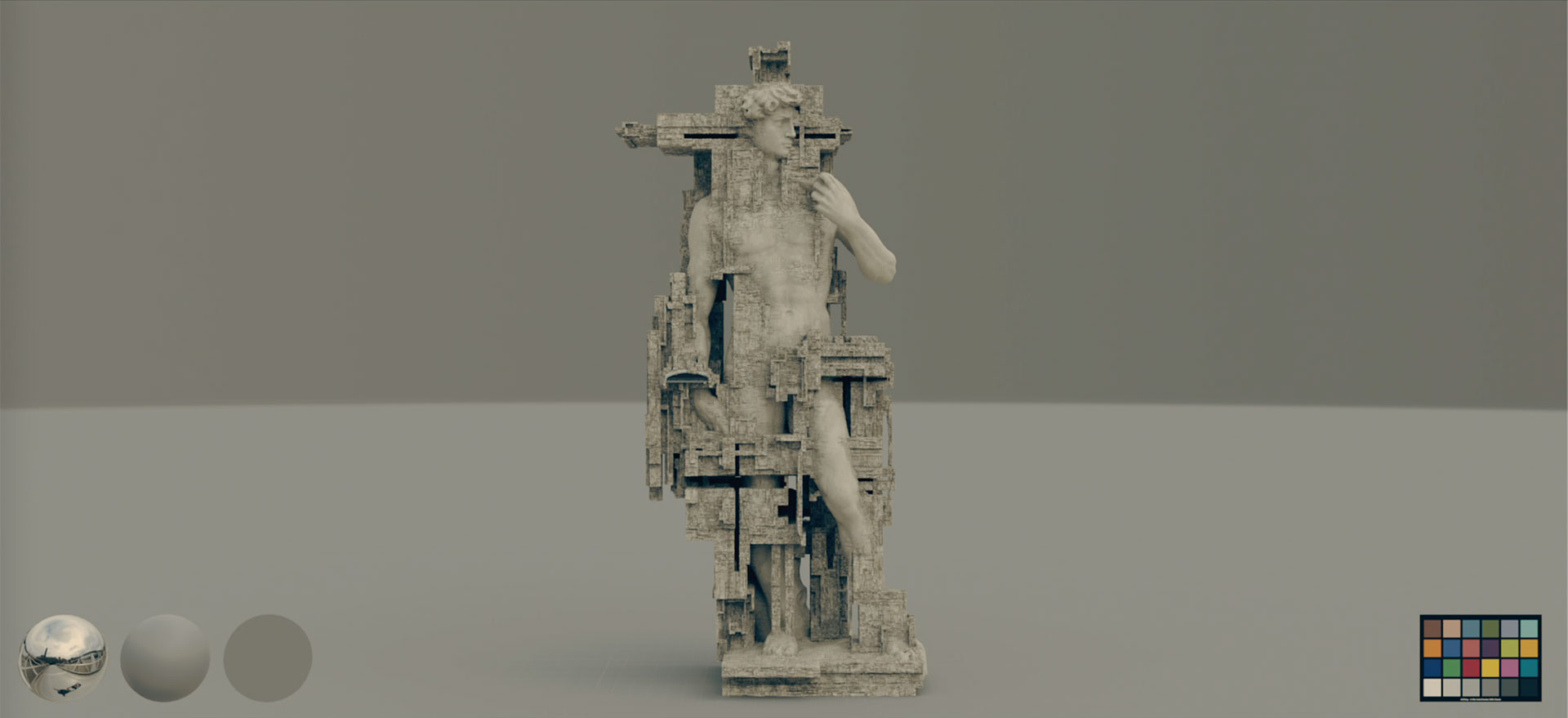

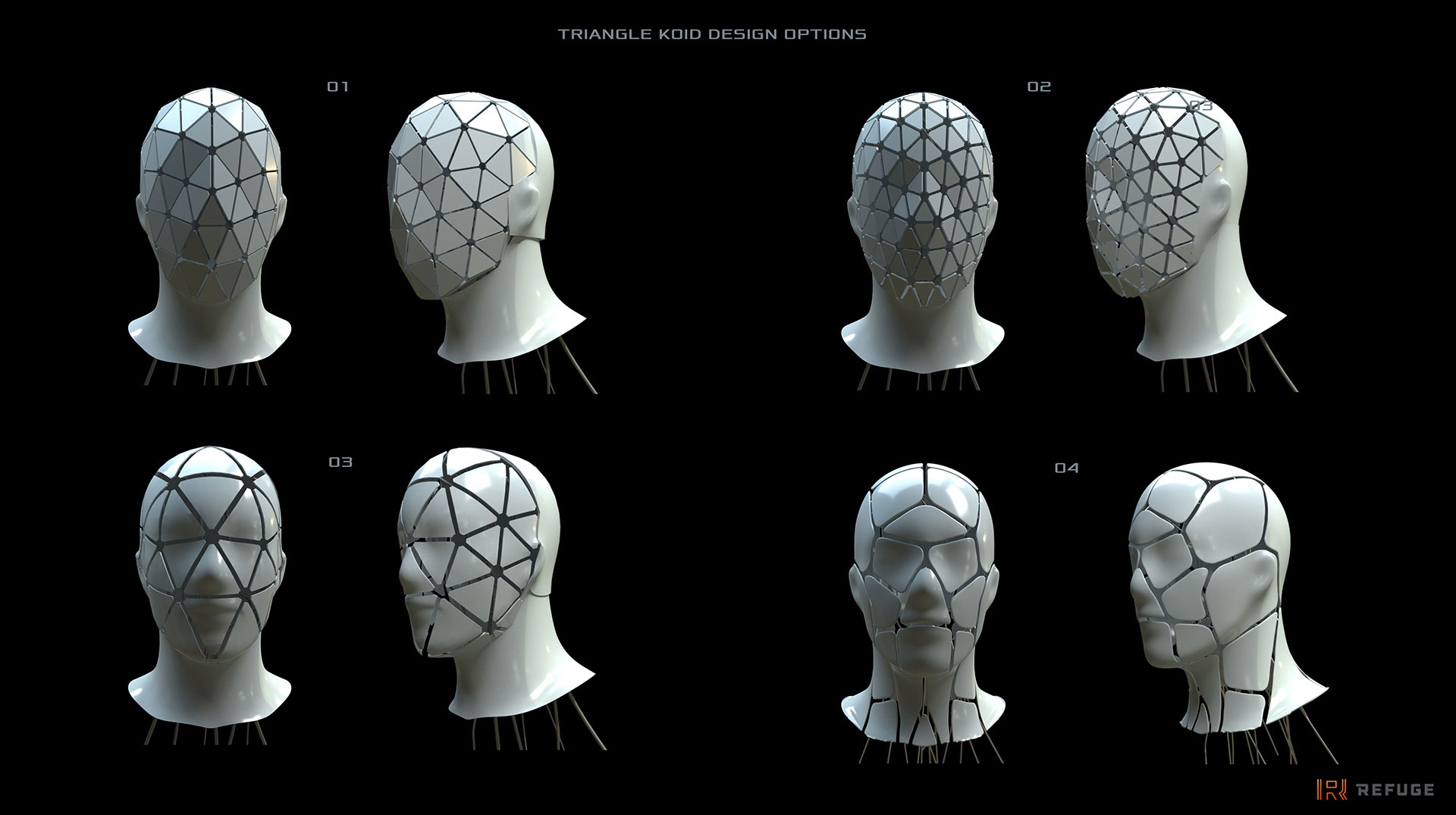

Jonah Nolan imagined them as being constructed of interconnected triangles of lenticular lenses that can project video images, with air gaps between the triangles in the head, so that we could see through them between the cracks. As with the air scrubbers, he wanted them to be a fusion of art and science. We started with painting clean plates behind each koid and doing experiments on various design options. Refuge in Portland led the koid design and execution. We finalized a design where the koids are made of nanobots that can be assembled using material from the surrounding environment, that build up along a central core of fiber optics, with the body and heads formed out of the interconnected triangles.

Can you tell us more about the face work for the robots?

Originally, all of our koids were supposed to be the generic white servant koid design or play artistic animation on the triangles. But as the concept evolved, our producers decided that two of them needed to look like 3D representations of two cast members. This necessitated making 3D versions of the actors that could be projected on the triangular lenses of the koid faces. It needed to look like each triangle was playing back video of part of the actor’s face. To do that we set up volumetric capture sessions at Dimension Studio in London with both actors to make the 3D assets.

However, the volumetric capture didn’t have the resolution to look fully photo-real in extreme closeups. The 3D models looked like video game assets. So Refuge came up with a way to use deepfake technology, using sample footage of those actors from other scenes, to add detail to renders of the CG assets. That helped us get past the ‘uncanny valley’ inherent in so much 3D character work.

The series is full of motion graphics. What kind of references and influences did you receive for that?

It was a mixture. Some interfaces, like Flynne’s game control watch and Ash’s Orb, were driven by concepts from our art department and our director’s storyboards. But a lot of it was driven by our editors, who were using the graphics to help tell the story. This was especially true in episode 2’s battle with the mercenaries. We needed to show how our heroes used their haptic implants to visualize the battle from a drone’s point of view, and then use that information to coordinate their defense of the house. So our editors mocked up demo screens with key beats that they needed, and we refined those designs with our design partners.

How did you work with the SFX and stunt teams for the action sequences?

Stunt sequences are always worked out in meetings between VFX, the stunt coordinator, special effects, and the director of photography. We start with the director’s storyboards or a previz done by the stunt team, and then figure out what aspects are best handled by which department. Will there be wires or stunt pads that must be removed? Will any weapons need to be CG for performer safety? Will the stunt be filmed on the set or on bluescreen? That kind of thing. But always we start from the point of “what’s safe for the performer to do for real, and what has to be helped by VFX?” Because performer safety is always the primary concern in any stunt.

Which stunt was the most complicated to enhance?

At one point, Tommy’s police cruiser is T-boned by a car with an invisibility cloak. There were about a dozen shots from outside and inside the SUV. There was a lot of stunt rigging on the vehicle that had to be removed, all the wires and chains that kept it rolling across a grass field. But also, the police cruiser didn’t have the damage from being T-boned, so Futureworks added that by replacing the exterior side panels of the SUV with a crushed CG version that tracked to the real SUV as the vehicle was rolling.

How did you enhance the gore aspect?

There wasn’t a lot of gore in our show. It was mostly traditional digital blood squibs for bullet hits or stabbing. And we had one scene of eye surgery where we had to composite together practical makeup prosthetics with plates of our actor and make them look extra nasty to elicit a primal reaction from the audience when they see an eye pulled out of an eye socket.

Did you want to reveal to us any other invisible effects?

There are three invisible effects we’re especially proud of.

First, Crafty Apes did a magnificent job with our triple amputee character, Conner, who moves around on a Segway-like monowheel. The work to remove his legs and arm and replace them with CG stumps, while preserving the practical special effects monowheel behind them, was very complex.

Secondly, one of our characters is an ultra-rich kleptocrat, who has genetically engineered a couple of extinct Thylacines (Tasmanian Tigers) ala Jurassic Park. They are visible in the background in a couple of scenes. We filmed trained dogs on set, and then Zoic replaced most of them with CG Thylacine parts.

Lastly, two scenes take place in virtual reality games. We filmed these as normal live action scenes. But then Kontrol Media found a way to train an AI using video game footage to use deep fake techniques on our dailies to make the actors look like Unreal Engine metahumans and give the scenes overall a more game-like look and feel.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

Because filming was done during the peak of the Covid pandemic travel restrictions, neither Jay nor I could travel to London for prep or principal photography. We’re both Los Angeles based, so filming in London, and doing the postproduction work at companies all around the globe, pretty much guaranteed that I’d be on call 24/7 to deal with various emergencies or to answer questions from our creative partners or our on-set team. All of that coordination was done via remote video conferencing.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Our first episode opens with a miniature recreation of the Battle of Trafalgar on a lake in a park. But we’re in the middle of it, between two ships, and it’s meant to feel like we’re in a movie like Master and Commander. It takes about 30 seconds before the audience realizes that it’s miniature boats in a public art piece. That was a lot of fun. Zoic used Unreal Engine to do post-viz with us, so they could set the position of the ships in real time on a zoom call, then they added all the detail and dynamics once that was approved.

Also, beloFX really hit it out of the park with the sequence of the Conner peripheral body being 3D printed.

What is your best memory on this show?

Honestly, it’s the people we worked with. Jay and I assembled a great in-house team consisting of a production manager, two coordinators, a VFX editor, two assistant VFX editors, and an in-house After Effects artist. And going to work with them each day was a joy. They were just fun people to spend your day with. But also top-notch at everything they did for the show. Consummate professionals.

How long have you worked on this show?

I just recently finished after 18 months of prep, shooting, and postproduction.

What’s the VFX shots count?

About 2,500 shots over 8 episodes.

What is your next project?

I don’t know yet. I’m just starting to talk to people about upcoming projects. And we’re still waiting to hear if Amazon will pick up a 2nd season of The Peripheral.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

Watching Blade Runner in a theater in college convinced me to switch majors from aerospace engineering to set and lighting design. But honestly, what gave me a passion for storytelling and VFX wasn’t movies, it was TV. Television was my babysitter and my inspiration growing up. Wild Wild West, Lost in Space, the original Battlestar Galactica, Star Trek: TNG, Babylon 5…all the great sci-fi series from the 60s to the early 90s convinced me that a career in VFX or animation for TV is where I needed to be. My first computer animation was trying to recreate a flying Veritech fighter from the Japanese anime Macross on a black and white 512K Macintosh Plus using Videoworks 2D animation software, around 1986. I’ve been hooked ever since.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

BlueBolt: Dedicated page about The Peripheral on BlueBolt website.

Prime Video: You can watch The Peripheral on Prime Video.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2022