Reflecting on 2021, Olivier Cauwet enlightened us about his visual effects endeavors on the film Eiffel. Now, he sheds light on his new collaboration with director Martin Bourboulon, detailing his involvement in both installments of The Three Musketeers.

How did you feel about working on a new adaptation of The Three Musketeers?

As I was finalizing the film Eiffel, Martin Bourboulon (the director) shared his enthusiasm for his next project. It was an ambitious venture with a stellar cast, a two-part adaptation of Alexandre Dumas’ « The Three Musketeers, » and he wanted me to join the team. This XXL project led us on an equally captivating journey both on-screen and in its realization. It wasn’t just the adaptation of the novel that struck me, although it’s a French literature classic, but especially the opportunity to immerse myself in the « cape and sword » genre, something I had never done before, and that we hadn’t seen in France for years.

Of course, I read again the novel, but it was Martin’s vision, Alexandre De La Patellière and Matthieu Delaporte’s adaptation, as well as Dimitri Rassam’s enthusiastic energy that propelled us into this journey. As I mentioned, it was truly an adventure in itself, with a shoot that spanned 139 days for the two parts D’Artagnan and Milady. We even mix the filming, where, depending on the sets, we could shoot scenes from both films on the same day.

How was this new collaboration with director Martin Bourboulon?

For his previous film, which had a significant amount of VFX, our first collaboration went very well. With this new project, Martin Bourboulon and Dimitri Rassam wanted to maintain that continuity, keeping the same spirit and trust in BUF for visual effects. Martin gives a lot of freedom to his entire team, which makes the experience extremely enjoyable. We truly feel involved at every stage, whether it’s during preparation, filming, or even editing. Martin communicates his vision, his impressions of what he wants to feel, the pace, and his directing intention. He’s always open to suggestions, allowing for real freedom of choice, while having a clear idea of what he doesn’t want. It’s a collaboration where the exchange of ideas and active participation in creation are highly valued.

What was his approach and expectations about the visual effects?

Visual effects must meet Martin’s high expectations, as he doesn’t want effects that overshadow the action or narrative. They are a tool for realization and must blend into the scenery, remain invisible, and I completely align with this vision. Martin likes to challenge his teams, and VFX is part of that. So, you always have to find a way to meet his directing expectations.

The shooting was done with an AlexaLF, 1960s anamorphic lenses, SerieC Expanded from Panavision, and a chocolate filter for the hue. Alive, always in a dynamic style, the camera is constantly in motion.

How did you organize the work with your VFX producer?

Simon Beausoleil is the VFX producer for both parts of The Three Musketeers. We organized the VFX shot production schedule in accordance with the editing process and established a delivery schedule for sequences based on their complexity and production time. The editing team had to deliver them to us as a priority to meet the post-production deadlines. We enlisted the help of two other VFX studios to assist us with each part. The Three Musketeers have a total of 806 VFX shots, with 637 distributed among BUF, CGEV, and Mac Guff. CGEV worked on the shots involving ‘d’Artagnan’, and Mac Guff handled those of ‘Milady’. A fourth VFX studio, IIW Studio in Lux laboratory’s offices, worked separately on 169 VFX shots.

How did you choose these studios?

BUF expressed a desire to collaborate with CGEV. Therefore, we proposed a collaboration with them on ‘d’Artagnan’. David Brochard supervised their work, and Marion Frelat was their producer. For ‘Milady’, it was natural for us to turn to Mac Guff, with whom we had previously worked on Eiffel. I wanted to relive that experience. Dan Rapaport supervised their work, and Mathilde Sonrier was their producer.

Can you tell us how you divided the work between them?

We decided to assign each studio one of the two films so they could take ownership of the project. CGEV took charge of the first part, ‘d’Artagnan.’ They handled the opening sequence in the rain, worked on extending the streets of the Musketeers’ hotel, created CG crowd scenes to enhance the extras, and dealt with various elements such as cleaning up anachronisms and touching up sets, thereby contributing to the visual aesthetic of the film.

As for Mac Guff, they worked on ‘Milady,’ the second part. Their involvement included several continuous shots, including the fight between d’Artagnan and Ardanza, as well as the final battle between d’Artagnan and Milady in the burning outbuilding. They also removed anachronisms and made set touch-ups.

What was a typical day for you during filming and post-production?

During the 8-month filming period, I was nearly there every day. I was called in with the direction team to prepare for the day. Even though most major issues were sorted during location scouting, there were always adjustments to be made due to changes or new ideas. I was primarily in contact with Carole Amen and Juliette Crété, the first assistant directors, and their teams, as well as Nicolas and Martin.

Overall, I was alone on set, my equipment traveling with me in the camera truck. In addition to my supervisory work, I gathered camera information, took necessary photos on set, HDRI with the Theta, and I had a small Leica Lidar with me, so I also scanned the sets. But on large sets like Compiègne or Saint Malo, where there were two teams, I enlisted the help of Aurélien Marquaille to assist me and gather data (set and extras photos, Lidar, HDRI, etc.). There’s also Marion Eloy, an artist I’ve been working with for a long time, who accompanied me for 2 days on the cliffs shoot in Etretat.

During filming, for marketing and production reasons, we had to urgently start VFX work on the continuous shot of ‘d’Artagnan’ fighting alongside the three Musketeers in the St Sulpice forest. We had to deliver it before the end of filming. So, I supervised the work daily from the set, and Marion Eloy oversaw the team in Paris. I was with Martin daily, so I could show him progress regularly.

At the end of filming, back in the BUF offices, I organized the internal workflow and worked with Simon on exchanges with editing, Lux lab, and other VFX studios. Simon and I hold a review twice a week with the whole team in our screening room. Since I work on the shots daily within the team, the artists can approach me anytime. We also hold a weekly syncsketch review via video with CGEV or Mac Guff during which we exchange with David, then with Dan on the shots they worked on with their teams. Throughout the editing periods, I frequently exchanged with the editors of both parts, Célia Lafite Dupont (d’Artagnan) and Stan Collet (Milady), to build VFX sequences. We regularly presented VFX to Martin, every two weeks at the beginning of each part, then very quickly every week at Lux, where Fabien Pascal, the film’s color grader, could adjust the color grading during the session.

What are the different outdoor filming locations?

There are approximately 80 sets, so I won’t list them all. We mainly filmed in the Île-de-France region and in Paris. At the Louvre, Place des Vosges, in St Germain-en-Laye, at the Château de Fontainebleau, at the Château de Chantilly, at the Château de Pierrefonds, at the Château de Farcheville, at the Abbey of Longpont. Then in Melun, Compiègne, Troyes, St Malo, and Etretat. And others…

How did you approach the creation of the various environments, especially La Rochelle?

Always with the same philosophy, we film in an existing set, to have the playing space, the light, and then we touch up or completely remake the set in VFX. This allows us to have an atmosphere and to maintain a dynamic and realism with the camera and actors. Whether it’s for the streets of Paris, the cliffs of Dover, or La Rochelle.

To recreate La Rochelle, a port and fortified town in the 17th century, Saint Malo intra muros was the perfect location to film. We had all the sets in the same place to shoot our sequences. The town hall, the Fort National, its beaches, and its ramparts provided a base for recreating La Rochelle.

We only kept the ramparts of St Malo, then reconstructed the city of La Rochelle in CG based on topographic maps and paintings from the 17th century. It was important to instantly recognize the city by its architecture, its towers of St Nicolas, of the lantern and of the chain, as they were at that time. For the needs of the screenplay, we added a forest on the edge of the city where the musketeers’ camps are located.

What was the most challenging environment to recreate?

The cliffs for the horse chase scene in ‘d’Artagnan.’ Martin wanted to film this sequence like a car chase, very dynamic, with horses colliding and galloping very close to the edges of the cliffs. We needed a sense of vertigo, danger, and the risk of falling. For obvious safety reasons, it was impossible to film stunt performers near cliffs.

So the idea was to recreate the entire environment in CG. We found a field in Etretat with enough space to film the riders in action and modify the terrain for stunts. We were the second unit and were shooting at the same time as the main unit to match the lighting since they were filming the end of the sequence. We filmed the stunt performers (Marco Luraschi and Laura Cassagne) with a drone for aerial shots and a crane mounted on a buggy for action and ground falls.

For initial editing purposes, and to do face replacement where needed, I organized a green screen shoot with the director and François Civil and Eva Green. With cinematographer Nicolas Bolduc, we replicated the lighting and camera angle for each shot. I spent a day with a drone team (Full Motion) to film the cliffs in Normandy under the same lighting and tide conditions. We used photogrammetry with these elements and recreated a CG cliff adapted to our scene. We added all the vegetation in CG, from grass to bushes and rocks, to create obstacles and enhance the sense of speed for the camera. There was a significant amount of tracking, masking, and rotoscoping work done by BUF’s graphic artists.

For close-up shots of the actors, we filmed them at the Bry studios, riding mechanical horses that we inserted into the cliff environment. It was a very enjoyable day of shooting. The entire sequence was filmed during daylight, and then Fabien Pascal graded the night scenes at Lux with Nicolas Bolduc. »

How did you create the English ships and also their destruction?

We started from a 17th-century CG base of ships, which Yann Austin’s team modeled and textured. There are still some replicas of three-masted ships from that period today. So, we had plenty of reference photos and, of course, paintings as well. All the ship plans are fully CG, so we recreated the entire environment with the sailboats. Only the onboard explosion plans are SFX on a green screen. We shot them docked in St Malo.

For the wide shots, the destruction is solid dynamics for debris and mast breaks. The sails and ropes are managed in cloth simulations. Explosions and smoke are simulated with our pyro algorithm. I remind you that at BUF, we only work with proprietary software. We have a team of developers who continuously improve and adjust our software suites to meet project needs.

For « Milady, » we worked extensively on the development of foam dynamics (white water), which we hadn’t done before at this scale.

There are many long continuous shots, especially during the battles. Can you tell us about your work on this kind of shot?

In preparation, Martin immediately expressed his desire to stage the fights in long continuous shots. He wanted the viewer to be immersed, plunged into the action, experiencing the tension in real-time. He knows that VFX has a role to play, especially in transitions, weapons, injuries, stunts, and environments. He lets the departments work together and present proposals to him, which he then builds upon. The choreography of the fights is presented by Dominique and Sébastien Fouassier, stunt coordinators. They define the action, whether it’s the actor or the stunt performer facing the camera at a particular moment. Then the director of photography, Nicolas Bolduc, gets involved, setting up the frame, the lighting, the technique, readjusting positions and rhythms. So, between actor-stunt performer changes, stunt setups, horses, the various cameras used, Alexa LF anamorphic, DJI drone, and the length of the shots, there are many transitions to find and make.

My role was to define how to technically make the transition. Sometimes the transition was obvious, dictated by the staging, in a panel, a natural cut, etc. But sometimes we had to make transitions within the action, with the bodies, the set, so you had to find a way to address it. And then there were also changes, improvisation, which meant everyone had to rethink things on the spot. It’s intense, but very exciting to do.

For the swords, the actors and stunt performers would stab their opponents on the side, and the VFX would replace the blade in CG to make it pierce the body. All throwing weapons are in CG. For a shot that was too dangerous in the fight, the dagger blade was entirely in CG. When we shot the long continuous shots, I had a Qtake operator, Esteban Perrin, by my side, with whom I would create VFX mock-ups live on set. This allowed us to quickly readjust the action, the frame, or validate the shot. The shot was built up as we went along, and in the end, we already had the entire sequence mocked up.

For the sequence shot of the musketeers in the St Sulpice forest, there are 11 VFX transitions for a 3-minute shot, which we shot over 3 days. And since we were outdoors, we had to deal with weather uncertainties, sun, clouds, rain… One of the VFX achievements, among others, was adding sunlight to the forest shots that were too dark. I really loved those moments, where you feel like we’re building something together.

What was the most difficult cut to make during the long continuous shots?

As soon as there is improvisation in this kind of long shot, it complicates everything. It’s not due to a change in the staging, but simply due to lack of time. We were running behind schedule, and the decision had to be made to remove a part of the planned shot to shorten the shooting time. The previous part had just been shot with a horse impacting a soldier and exiting the frame for the continuation of the shot. But with this change, neither the exit from the frame nor the camera movement worked to connect to the next part. We had to redo the entire set in post-production to redo a camera movement. We reused a bad take in which the horse exited at the right place, but the impacted soldier wasn’t positioned correctly. So we had to composite another take of the soldier that I had filmed separately at the end of the day. It was makeshift. All of this for barely 3 seconds of the shot.

How was the collaboration with the SFX teams and the stunt performers?

We were very collaborative. Dom and Sébastien Fouassier, the stunt coordinators, like to challenge the VFX team because they need it to meet Martin’s demands. It was very easy and enjoyable to work with them. There are always surprises, which adds excitement. Mario and Marco Luraschi need no introduction. You can ask them anything, respecting the horses, it’s never a problem.

The same goes for the SFX team (BigbangSFX) led by Jean Christophe Magnaud. The remarkable work on explosions, debris, fire, everything was done very smoothly between us. The team for climate effects led by Olivier Nguyen was always in communication, for smoke and fire throughout the shoot. There’s also Stéphane Linet, the armorer, with whom I worked closely. Depending on the shots and safety, the gunshots were either done live or in VFX.

The production provided me with two days of SFX element shooting in the studio, to cover all the needs following the shooting of both installments. Gunshots from pistols and rifles and flames for the barn fire. Plus numerous elements for the film. There were many and significant collaborations with these departments, with a really pleasing result.

What was the most challenging stunt to enhance?

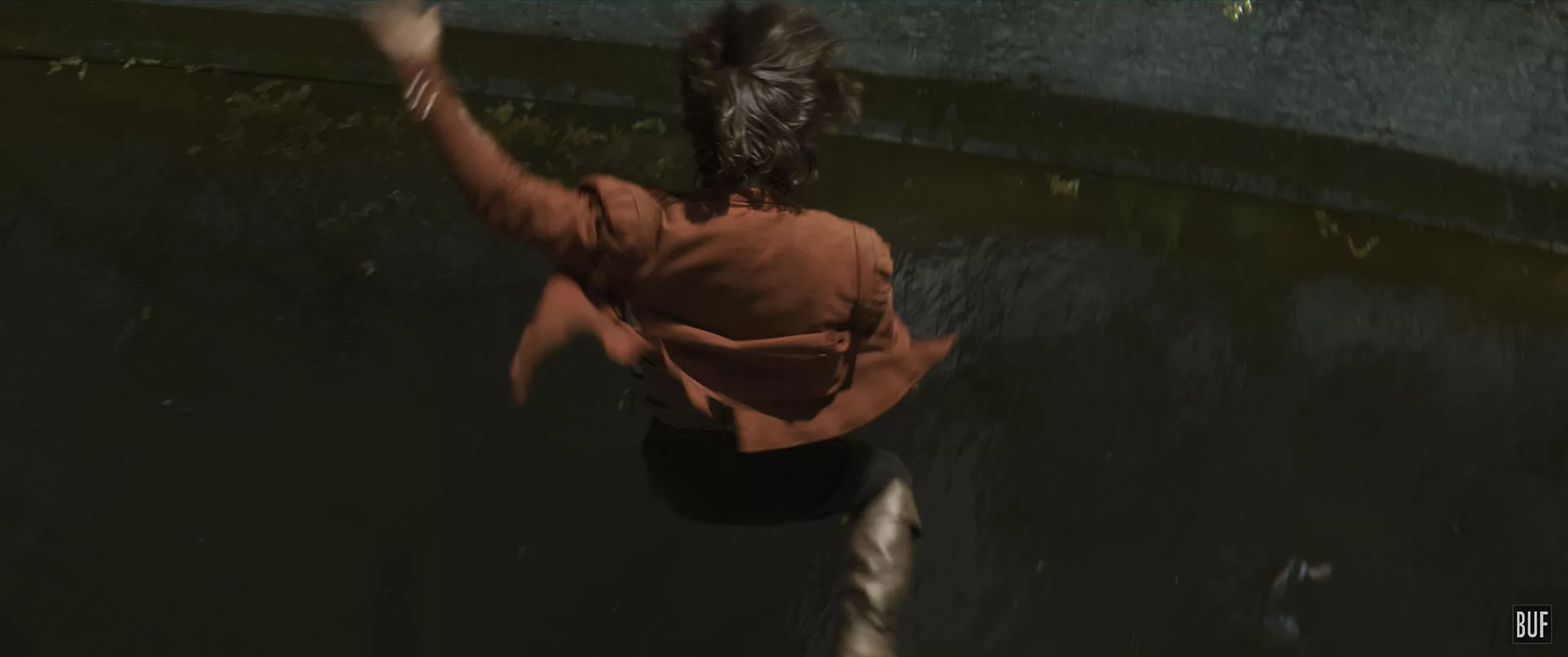

That would be d’Artagnan’s leap from the ramparts at the beginning of the Milady sequence. It’s a continuous shot where the camera follows d’Artagnan and Milady escaping their pursuers by jumping from the ramparts. The camera tracks d’Artagnan all the way into the moat.

Of course, there are several VFX transitions from François Civil to the stunt double. But also, between the moment Marco Luraschi (the double) clears the battlements and the point where he falls. We didn’t have permission to set foot in the moat, which wasn’t deep enough anyway. So, we shot Marco suspended from a crane, with Sébastien Fouassier operating the camera just above him. They were held by cables and dropped above a pool until Marco hit the water. Another constraint was that the camera must not touch the water at all… So, I stitched all of that together in post-production and recreated the entire moat and water in CG during the fall, as well as the passage through the water.

As an anecdote, the parts of the sequence with François were shot nearly a month after the stunts. So, there were different lighting and atmospheres to match.

The final battle takes place amidst a raging fire. How did you create this fire?

It was quite a challenge taken up by all the teams. It’s a 4-minute long continuous shot filmed over 2 days at the Bry studio, set up with wood and plaster.

The idea was to have a real fire base for the lighting and atmosphere. Stéphane Taillasson, the production designer, conceived the set taking into account the desires and needs of the stunt performers. He also worked closely with the SFX team so they could install their pyrotechnic network and controls during construction.

JC Magnaud (SFX) established a safety perimeter around the actors and camera crew. Any fire close to them would be CGI. The emergency exits planned by the set decoration would be set ablaze using CGI. Flying embers, heat effects, and falling flaming debris would all be CGI. We installed LED ribbons for lighting in the areas of the set where we would add fire. It helps with integration and serves as trackers.

We made 11 cuts for this shot. The fire is lit locally and only in front of the camera. As soon as the camera pans too much, a cut is necessary. The segments couldn’t be too long because it was taxing for the actors and crew. It’s worth noting that due to the carbon monoxide the fire emits, roughly speaking, you shoot for a minute, then you’re out for 10 minutes. To be able to add the fire in CGI, I filmed flame elements. We didn’t have the budget for CG fire, and I like using photographic elements. The fire composed in CGI matches exactly the fire from the shoot.

With the storyboard of the continuous shot, I analyzed the axes and requirements. The next day, I did a lidar scan of the set, and we filmed flame and fire elements alongside the SFX team. Fire-engulfed posts, barrels, the ground floor when we’re upstairs, etc… Then, I filmed fire elements against a black background to complement wherever necessary.

It’s the Mac Guff team, supervised by Dan Rapaport, who rigged all the CGI for this sequence, both interior and exterior of the set. They did a splendid job. We built this sequence step by step; it was a lengthy process. There was a lot of tracking and masking work. They created several CG set extensions with fire and smoke, integrated all the fire elements throughout the 4-minute shot, added heat effects, the CG dagger, and most importantly, handled the 11 transitions, some of which were quite tricky. There are many moments on the upper floor where we transition from actors to stunt performers and back to actors. The plan’s dynamics work very well. The end of the shot with Milady and the debris falling in flames was a beautiful challenge. All the elements filmed in spherical are reworked and composed by Mac Guff to create the illusion of the drama. The entire set is rigged and extended in CG to add the fire behind all the actors.

Can you reveal some invisible effects to us?

I hope that there is plenty that is not seen, that the viewer remains immersed in the story.

What was the main challenge on this film?

The wide variety of VFX to be produced and to maintain the homogeneity and quality of the effects.

Is there something that has given you sleepless nights?

The boat sequence.

What is your best memory about this production?

Difficult question. There are a lot of great memories from filming and post-production. I admit that I really enjoyed the team screenings, because it was the first time that I really experienced the film as a spectator, and alongside the artists who discovered their work at the heart of the film.

How long did you work on this film?

From preparation, through the 8 months of filming and the 9 months of post-production. It’s been roughly 2 years.

The 9 months cover the production of the VFX of d’Artagnan and Milady. Fortunately there was the Christmas break between the two post-productions 😉

What is the VFX shots number?

806 VFX shots.

What is your next project?

I have just finished filming and started post-production on Monte Cristo, adapted and directed by Matthieu Delaporte and Alexandre de La Patellière, produced by Chapter2 and Pathé. In between, I shot a medium-length film with Leos Carax, the post production is to come.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

BUF: Dedicated page about The Three Musketeers: Milady on BUF website.

IIW Studio: Dedicated page about The Three Musketeers: Milady on IIW Studio website.

Mac Guff: Dedicated page about The Three Musketeers: Milady on Mac Guff website.

BUF: Dedicated page about The Three Musketeers: D’Artagnan on BUF website.

IIW Studio: Dedicated page about The Three Musketeers: D’Artagnan on IIW Studio website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2024