In 2010, Adrian de Wet explained the work of DNEG on THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE. He then worked on THE TREE OF LIFE, TOTAL RECALL, THE HUNGER GAMES: CATCHING FIRE, THE HUNGER GAMES: MOCKINGJAY – PART 1 and 2.

How did you get involved on this show?

I had seen the script for MEG (as it was called then, without the “the”) at various facilities in Soho every now and again over the last fifteen years. It was one of those films that just seemed to never get made. It went through many iterations with various directors – at one point I even think Guillermo del Toro was involved. At one point, Jan de Bont. Then in 2015, when it looked like it was finally going to get made, it was at Warner Bros and Eli Roth was at the helm. And then another change of directors: when I heard that Jon Turteltaub was taking over, I just had to go for it – having worked with him before, I knew the tone that he would go for, adding his own humour, taking it toward a more age-inclusive, family entertainment. And the prospect of Jason Statham beating the crap out of a giant shark in a Jon Turteltaub film was just too good to pass up.

How was the collaboration with director Jon Turteltaub?

Jon is a very collaborative guy. He encourages everyone to pitch in with ideas, and to not hold back. When we were in prep in New Zealand we would have daily creative meetings, which would consist of Jon, Tom Stern (DP), Jim Madigan (2nd unit dir.), Geoff Hansen (1st AD) and myself, locked in an office for hours at a time, going through the script, pitching ideas for sequences, which would then result in a brief to a story board artist, and eventually I would take this to one of our previs companies (either Unit 11 or Halon). In total we pre-vis’d around nine sequences like this.

What was his approach and expectations about the visual effects?

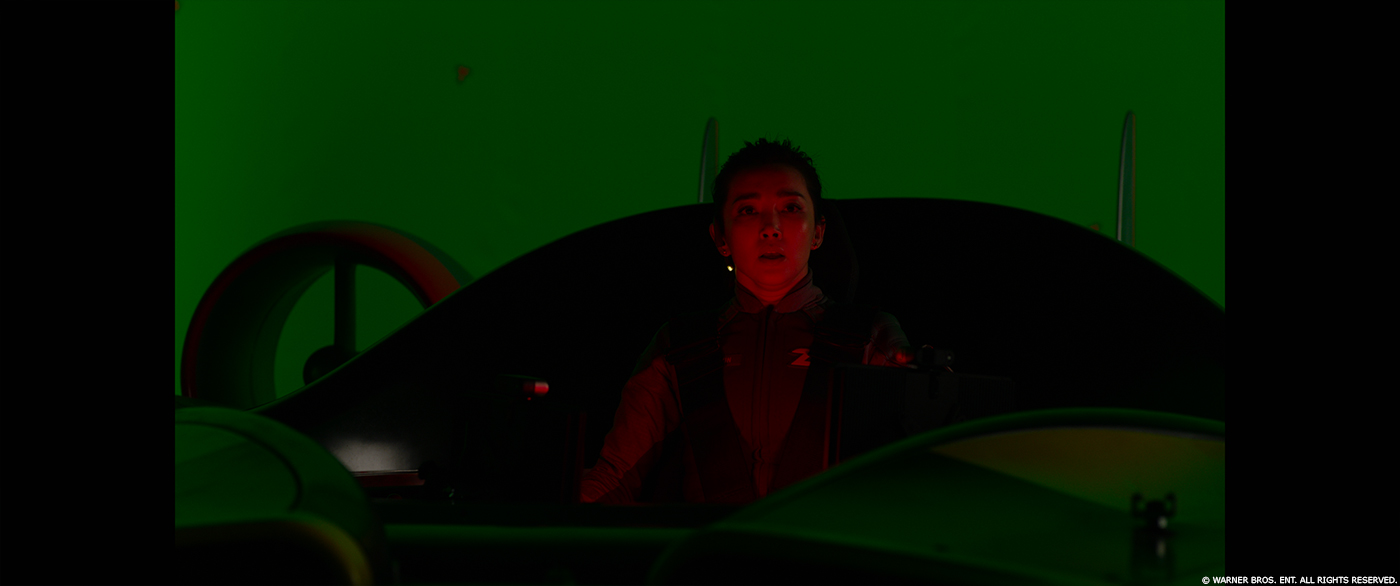

Jon has, rightfully, always held the opinion that visual effects are there to service the narrative, and a big flashy visual effect should not be an end in itself. Also he feels that VFX should always be grounded in some physical reality, and should not look like “visual effects”. Basically, he feels the same way about visual effects as every single visual effects artist out there. However, on this movie, where the overwhelming majority of the shots are big complicated VFX shots, including the eponymous Meg, we were faced with the daunting challenge in post of having to put together an entire movie based on a creature that didn’t exist yet. Steve Kemper (editor) had to rely heavily on Ray Bushey (VFX editor) to come up with some great looking temps. Otherwise we were cutting with previz, or, if we had to, we would have a title card on black. There was also a ton of green screen in the first cut – a huge portion of the film was shot in the Ocean Surface Tank, surrounded by green. All that green had to eventually be replaced with a digital ocean environment, which would eventually be created by Scanline and Soho VFX, but to get something fast and cheap for the edit, we relied heavily on our in-house compositing team. Also, the third act: the entire glider chase scene at the end of the film was shot on a stage on green, but luckily we could rely on Sony Imageworks to provide us with great looking temps for that sequence. We also enlisted the help of Halon, whom we had used for Previz, for postviz in the second and third act. So the expectations of the visual effects were two-fold: (1) To make a plausible and scary creature that would be the co-star of the movie, and (2) to create all the missing stuff that made the movie presentable. Which was, basically, most of the film. The pressure was on.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer and at DNEG?

By the time Steve Garrad (VFX producer) came on board we were already in New Zealand, at Auckland Film Studios, in prep. I’d previously broken down the script with Rhonda Gunner (VFX consultant) and we had the work divided up into three groups of various shot types: there was the deep underwater sequences that appear mainly in the first act, then all the action on the boats and just under the surface in the second act, and finally the carnage on the beach and the glider chase and the big finale in the third act. The vendor allocations were split along those lines, with the deep water environment shots and the gliders / subs being launched going to DNEG, all the shark action on the surface of the water, the shark cage scenes, and the beach carnage in China going to Scanline, and the rest of the third act including the glider chase, the breach / eye stab, and the death of Meg all going to Sony Pictures Imageworks. As we got further into it and realised how much work we really had to do, we enlisted four more facilities: Image Engine, Soho VFX, Umedia, and Instinctual VFX.

Can you tell us more about the previz and shooting process?

As soon as I was on the show, in April 2016, I was tasked with the job of getting storyboards and ultimately previz created for all the big VFX sequences. The folks at WB were very keen to prep all these big action sequences to as great a level of detail as possible, even to the extent that we could block out cameras and send pan and rotate data from virtual cameras to the motion base rig that moved the submersibles. However, Jon is always having new ideas, always looking for ways to make the action better, and that includes during shooting. This meant that the previz was used more as inspiration rather than an exact template of what to shoot.

What was a typical day on-set and during the post-production?

A typical on set day would be arriving at the stage at 7am, discussing the day’s shots with Jon, then with the VFX crew including supervisors from facilities, then meeting with Geoff Hansen (1st AD) to make sure that we could get what we needed in terms of data. The rest of the day would then be smooth sailing, with no unexpected hiccups or changes of plan. Ever.

In post, we would have a constant influx of material from facilities, which we would furiously review in the morning before Jon saw it… we’d decide what to cut in and show Jon, then the afternoons were spent in the editing suite with Steve Kemper, reviewing shots with Jon. Every day was like this.

How did you work with the art department to design this massive creature?

The art dept did some initial designs, but pretty early on, in prep, I started working directly with Scanline to move away from the concept art and get the model going.

Can you explain in details about his creation?

The main challenge was a creative one. The creature is described in the books as looking like a huge, albino, Great White. However that was really not what Jon Turteltaub wanted at all. He wanted something that looked prehistoric – and while it makes evolutionary sense for it to have ended up albino and blind after countless millennia in the total darkness of 10km deep, Jon felt that that didn’t work for his vision. Instead he wanted it to look gnarled, textured, aggressive, moody, and dark… most definitely not a great white. Great whites and other sharks can actually look a bit smiley and happy when you look at them head on – they have a big grin – so we designed a mouth that was less turned up at the sides. The shape and proportion of the Meg had to be addressed as well: when we modelled the Meg using correct shark proportions, it looked too sleek and thin, with a too-small dorsal fin. So we had to adjust proportions to Jon’s taste, which meant a fatter shark, with smaller eyes, and a larger dorsal fin. There were many iterations of the Meg body shape, from long and sleek to shorter and fatter. Too much of a bulbous shape destroys scale and makes it look like a tuna fish or a giant guppy; too lean and sleek makes it take on the appearance of an eel. To summarise, we invented a hollywood version of Carcharocles Megalodon that probably couldn’t exist – we even gave it eight gills, knowing that extant sharks either have five or seven – as something for the shark geeks to point out! But, you know, it’s a movie.

How did you handle the challenges due to his size?

We studied hours and hours of footage of great whites. Even though our beast is four or five times longer than a large great white, the topology and the hydrodynamics are similar. We had to make sure that our creature did not move too quickly or we’d lose the scale. But to keep the tension up in the final act, it had to travel quickly to chase our heroes and to provide peril. It was a fine balance.

Can you tell us more about the underwater lighting challenges?

The big question here was: do we go for something that looks completely real or do we go for something that looks cinematic, clear, deep and awesome? It was an easy question when put like that. We established a library of different looks: early in the story when Lori is at the bottom of the ocean in her sub discovering the world beneath the sulphide layer, we are really going for a beautiful deep ocean look, which is lit just enough by the exploratory lights to stop it being scary. Later, when Suyin is down there in her glider, we play it really dark, and have light only from her headlight beams which fall off rapidly into jet black. This was meant to be scary and tense for the giant squid attack. Even when the Meg shows up down here, you can hardly see it – that is the intent. Later on, when Suyin is in the cylindrical shark cage in the middle of the film, we are close to the surface, and so we can allow the tropical sun to shine through the water light the sharks, including the Meg. These scenes were meant to play as sunlit underwater scenes, intense blue in colour, and our intent here was to make the shark cage feel like this tiny little space capsule floating in an ocean of sunlit ultramarine which fades off to almost black at the bottom of frame. Finally for the glider / Meg chase in the third act, we played this like a shallow sunlit coral reef environment, which small hills and caves and coral arches to provide places to hide and visual interest.

The movie is taking us deep in the abyss. Can you explain in detail about the creation of this underwater environment?

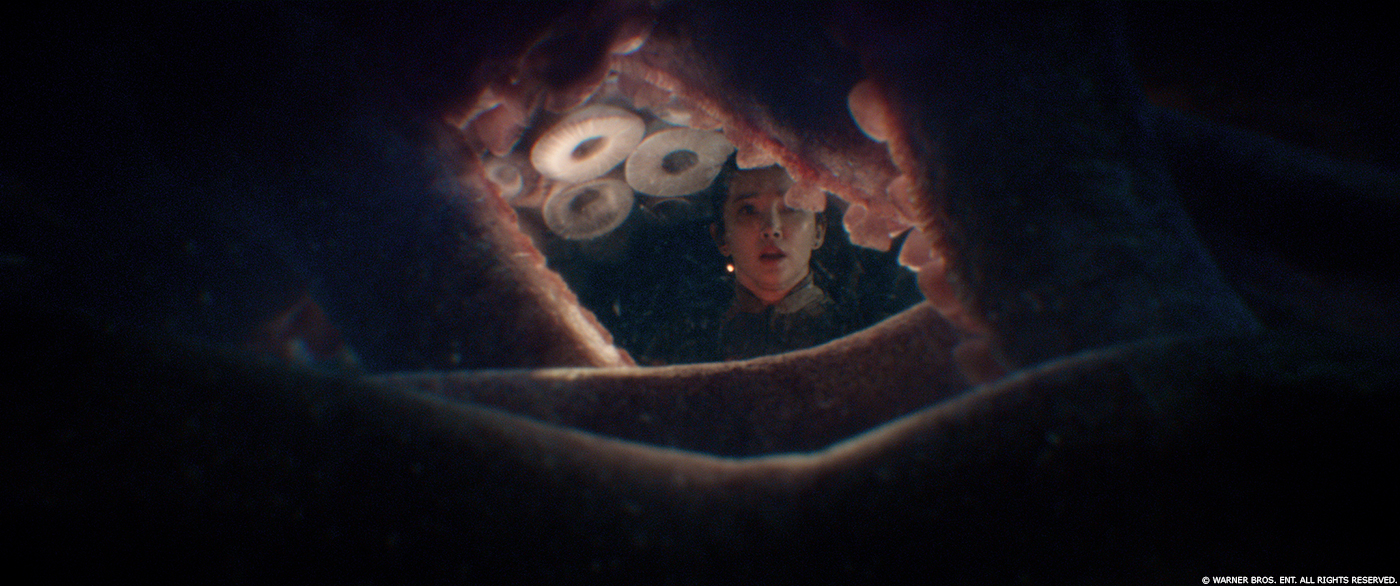

We did quite a bit of research here to try and figure out if this was at all scientifically plausible. The idea is that hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the deep ocean trench are spewing out superheated water rich in minerals and dissolved gasses, which, on contact with the colder water of the ocean, precipitate out into what looks like black smoke. This “smoke” rises up in large columns and then collects at a certain height above the ocean floor, creating a canopy, which, if you’re above it, looks like the bottom of the ocean. So that’s the idea. In the movie, the space underneath this floor/canopy in a hitherto unexplored world of mystery and wonder, and is home to all sorts of exotic hybrids and chimera, as well as the usual established deep-sea life forms such as giant tube worms, plankton, jellyfish etc. DNEG were given the task of creating everything here. They came up with a menagerie of creatures, all based on real-world animals which were altered slightly or fused with other animals to be new and unique. There are no plants down here due to there being no sunlight – everything you see is actually some form of animal!

How did you populate it with all those animals?

Ray Chen and his team at DNEG used their bespoke tools to establish the topology of the environment and populate it with the hydrothermal vents, and then tube worms, and deep sea corals. We then mapped out the sequences in this environment by placing virtual cameras within it, and then dressed in animals on a shot by shot basis.

Can you explain in detail about the water simulations and interactions work?

There was a lot of it! Almost all the ocean shots have some sort of digital water work. All the facilities had a hand in the water simulations. Obviously Scanline are famous for this, and their water simulations are some of the best I’ve seen. I particularly love their work on the capsizing boat scene. But there’s a lot of other CG water throughout the movie also, such as the scene when Jonas descends in his sub, and we see the water level rising on the screens in front of him. And, remember, a lot of the ocean surface is 100% digital when we’re on the boat. And all the wakes created by the Meg are digital. And that beautiful water surface viewed from below in the third act is really nice touch from Imageworks, as of course is their great moment when the Meg is killed and it splashes back down into the ocean.

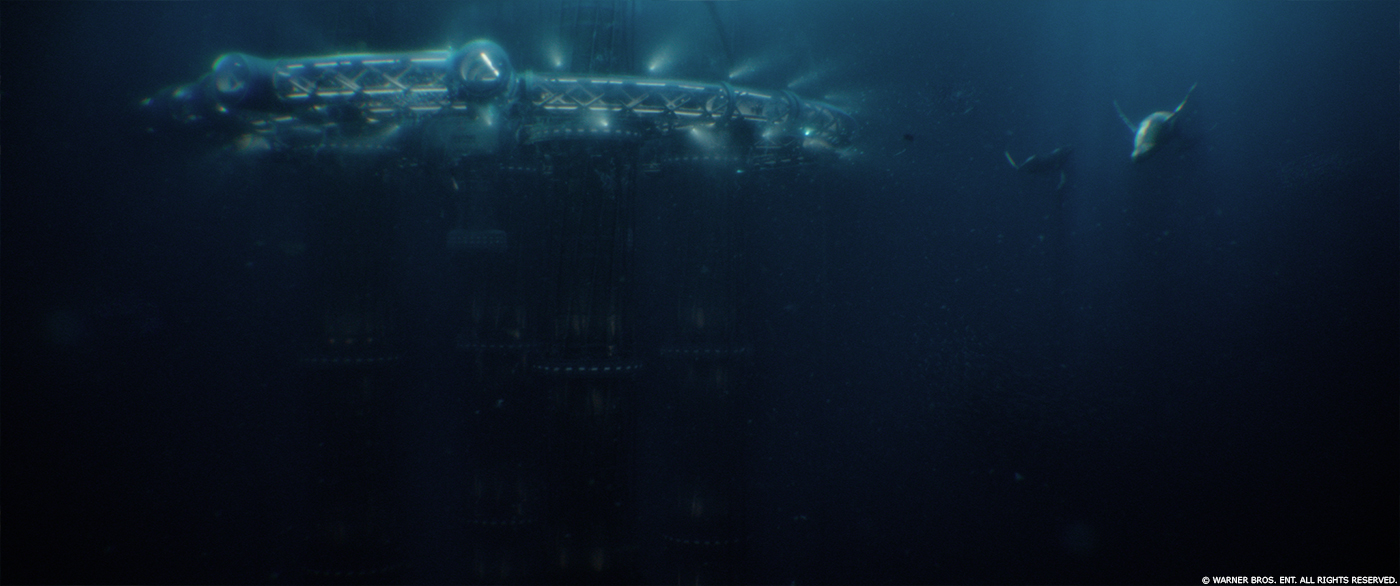

How did you create the ManaOne research facility?

This fell to DNEG. We had some concept drawings and a rough model from the Art Department. A section of the Observation Level (“O-Level”) was built as a set, but it was the struts only; no glass. We extended the set digitally and added digital glass with reflections. From the O-level we created views into the deep ocean, as well as views of other parts of the ManaOne.

Can you tell us more about the creation of the various underwater vehicles?

There were two types of underwater vehicles: the Submarines and the Gliders.

The submarines were three-person submersibles, such as the one that we see Lori, Toshi and the Wall in at the start of the film. We only really had the interior as a dressed set – whenever you see the exterior of a Sub it is always CG. The interiors were dressed, and we lined the cockpit end in blue perspex and backlit it so that we could use that as a blue screen but retain reflections of the crew and instrument panels etc.

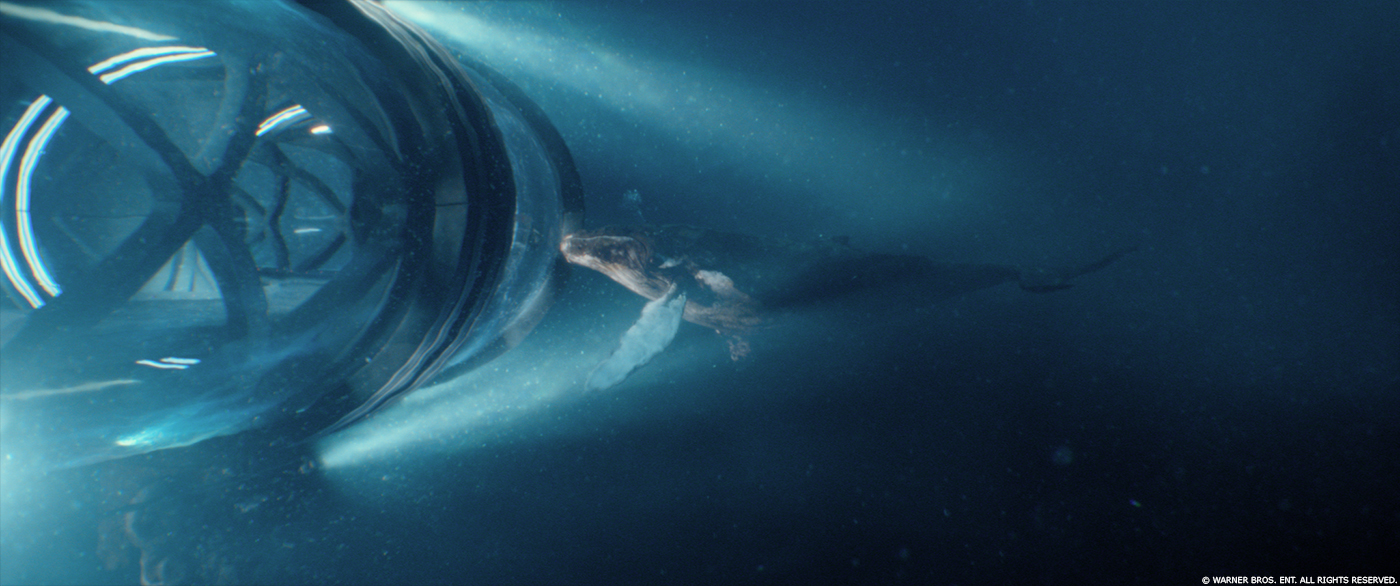

The gliders were the one-person submersibles that feature heavily in the third act, or when Suyin descends to try to save the crew. They were built almost complete, and situated on a hydraulic motion-base rig. The glider did not have a canopy – all the glider canopies in the film are digital.

How did you work with the SFX and stunt teams?

The VFX team worked very closely with the SFX teams in prep, in planning what they were going to do and what we were going to do, to make sure we didn’t double up on the work too much and to make sure that we could get all the data we needed from them such as the tilt and rotate data from the motion base rig on the Glider. For the stunts, there was quite a bit of planning for the third act, in the beach carnage scene, specifically the action on the platforms when we see people flying off as the Meg bites the platforms. All these action beats were previzzed so we could map out and rehearse the sequence.

The final battle shows literally Jason Statham fighting the Meg. How was created this sequence?

The Meg had to be killed in a way that was clearly a result of Jason Statham’s strength, resolve and skill as a fighter. In the book, the character Jonas kills the Meg in an outrageous way (I won’t say how) and we wanted something that was as outrageous and as awesome. So we chose this particular fight and method of death. But we wanted there to be a struggle, and we wanted there to be a lot of risk to Jonas, but mainly we wanted it to be an absolute spectacle of heroic man and brutal nature. We started off by beat-sheeting the entire sequence from the point at which Jonas and Suyin get lowered into the water in their gliders, get chased by the Meg, fail to blow it up, nearly get eaten, cause the helicopters to crash, right up to and including the death of the Meg. Then I took the beats to Halon, and they previzzed the entire sequence. The previz then went into revisions and finessing and was constantly being improved upon all the way into post. We used the previz on set when we shot Jonas and Suyin in their gliders; we inverted the previz glider moves to get real camera moves which made it look like the real gliders were moving through the scene when they were composited into our virtual environments. Sue Rowe and her team at Imageworks came up with a nifty way (Viewport 2) of mapping out the entire sequence using the shot footage composited into a basic 3d environment which was enough to prove that the concept was a success, and allowed us to screen the sequence.

For shooting the scene where Jonas’ glider is destroyed by the Meg and he swims out, this had to be shot in the tank, underwater, and not dry-for-wet. So we built a practical buck for the head of the shark with an eye for Jason to climb up on and stab. This had to be yanked around underwater at high speed by the SFX guys to replicate the shark’s motion, so it couldn’t be solid otherwise there would be too much impedance from the massive volume of water, so it was built like a wireframe, using steel rods. For the actual breach moment, with Jonas and the Meg in mid-air as he delivers the coup-de-grace, we built a solid buck of the shark’s face, and hoisted Jason up there and shot it in the parking lot from an extending crane arm at high speed.

Can you tell us how you choose the various VFX vendors?

I’d worked with all of these vendors, or at least people from these vendors, at some point in the past.

How did you proceed to follow their work of the various vendors?

We were posting in LA, and most of the vendors were in Vancouver. So at least we were in the same time zone. We would have cineSyncs every day.

Which sequence or shot was the most complicated to created and why?

Probably the breach shot / eye stab in the third act. There’s just so many moving parts – there’s the shot material consisting of Jonas on the fake Meg’s face, there’s the fact that it was shot at 96 fps, there’s the baked in camera move which really represents the move of the Meg plus Jonas falling away from us but only after a certain point when they’ve gone past the top of their arc – and there’s the whole physics and gravity question, plus what should the blood spurt be doing on an object that is falling away from us? There was certainly a lot of ingredients to this shot. And that’s not including the huge amount of simulated water that has to be added running all over the Meg’s face, and the muscle simulation of the shark, and a digital-double take-over of Jonas… the list goes on. All for one shot.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

The boat capsize scene in the middle of the film. It’s just a completely preposterous, ridiculous, outrageous, funny, unexpected, and totally iconic moment in the film and I love it.

What was the main challenge on this show and how did you achieve it?

The sheer scale and complexity of all the work. It was achieved by hiring the best people at the best facilities.

Is there anything specific that gave you some really short nights?

Preparing for screenings was always a little stressful. We had a lot of changes and obviously we couldn’t go into a screening with title cards on black telling us what we should be seeing! So we had to rush many hugely complex 100% CG shots through with a moment’s notice – and often we had to put version 1 in the screening. That was a little scary.

What is your best memory on this show?

Working with such amazing, talented, generous and patient people.

How long have you worked on this show?

I came on to the show full time in April 2016 and we wrapped in December 2017. So that’s 19/20 months total.

What’s the VFX shots count?

Not sure of the final number – somewhere north of 2’000 I believe.

At one point we were tracking around 2’600 shots.

What was the size of your team?

I actually don’t know! You’d probably have to ask each facility. Thing is that team size sort of varies a lot throughout the life of a project. It’s certainly the biggest show I’ve ever done, I can say that.

What is your next project?

I’m doing something exciting and very different for a new studio with a new distributor on a new platform. That’s all I can say right now!

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

DNEG: Dedicated page about THE MEG on DNEG website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2018