In 2017, Pablo Helman explained to us the work of ILM on SILENCE. He talks to us today about his new collaboration with Martin Scorsese.

Leandro Estebecoena has worked in visual effects for over 30 years. He joined ILM in 1996 and worked on films like TRANSFORMERS, IRON MAN, STAR TREK and RANGO.

Nelson Sepulveda began his career in visual effects in 1994 at Cinesite. He then worked at Centroplois Entertainment and Weta Digital before joining ILM in 2004. His filmography includes films like RANGO, THE AVENGERS, WARCRAFT and KONG: SKULL ISLAND.

Ivan Busquets started working in VFX in the early 2000s. He worked at Cinesite, MPC and ILM. His filmography includes films such as THE GOLDEN COMPASS, SUCKER PUNCH, ROGUE ONE: A STAR WARS STORY and BUMBLEBEE.

Stephane Grabli joined ILM in 2008. He worked on films such as RANGO, TRANSFORMERS: AGE OF EXTINCTION, STAR WARS: THE FORCE AWAKENS and JURASSIC WORLD: FALLEN KINGDOM.

How did you and ILM get involved on this show?

Pablo Helman // I was in Taiwan working with Martin Scorsese on SILENCE. One day we were speaking with him about technology and began discussing how we might approach making an actor younger. Scorsese mentioned that THE IRISHMAN was a project that had been on the back burner because there was no way to make it. So he emailed me the script and I read it overnight. In the morning I told him we were IN! That was in 2015.

Leandro Estebecoena // I started working on a test for THE IRISHMAN back in October of 2015. After the test, I worked on developing the hardware and software solution for the show and working on our show setup until we started full time in January 2017.

Stephane Grabli // In November 2015, I started working on the development of ILM’s Flux software to take it from a proof-of-concept to a production ready tool.

Nelson Sepulveda // I started on the project in April 2018 on some of the very first Flux solves. I also, worked on the development of the 2D tools we knew we would need and worked on all the digital to film matching processes as well as color pipeline integration.

Ivan Busquets // I started on the show during post, in June 2018. Together with the team in San Francisco, and worked on some of the first production shots, helping establish a workflow for the body of work that was to be done in ILM’s Vancouver studio.

How was the collaboration with director Martin Scorsese?

Pablo Helman // Scorsese is amazing to work with. He has an encyclopedic knowledge of cinema and, of course, a great eye and he always puts the emphasis on “feelings”. How he feels about the work you present to him, how it compares to what he felt on the set. Also, how the effects work follows his vision for the picture overall. He is a master at the craft, he doesn’t HAVE to collaborate, but he does!

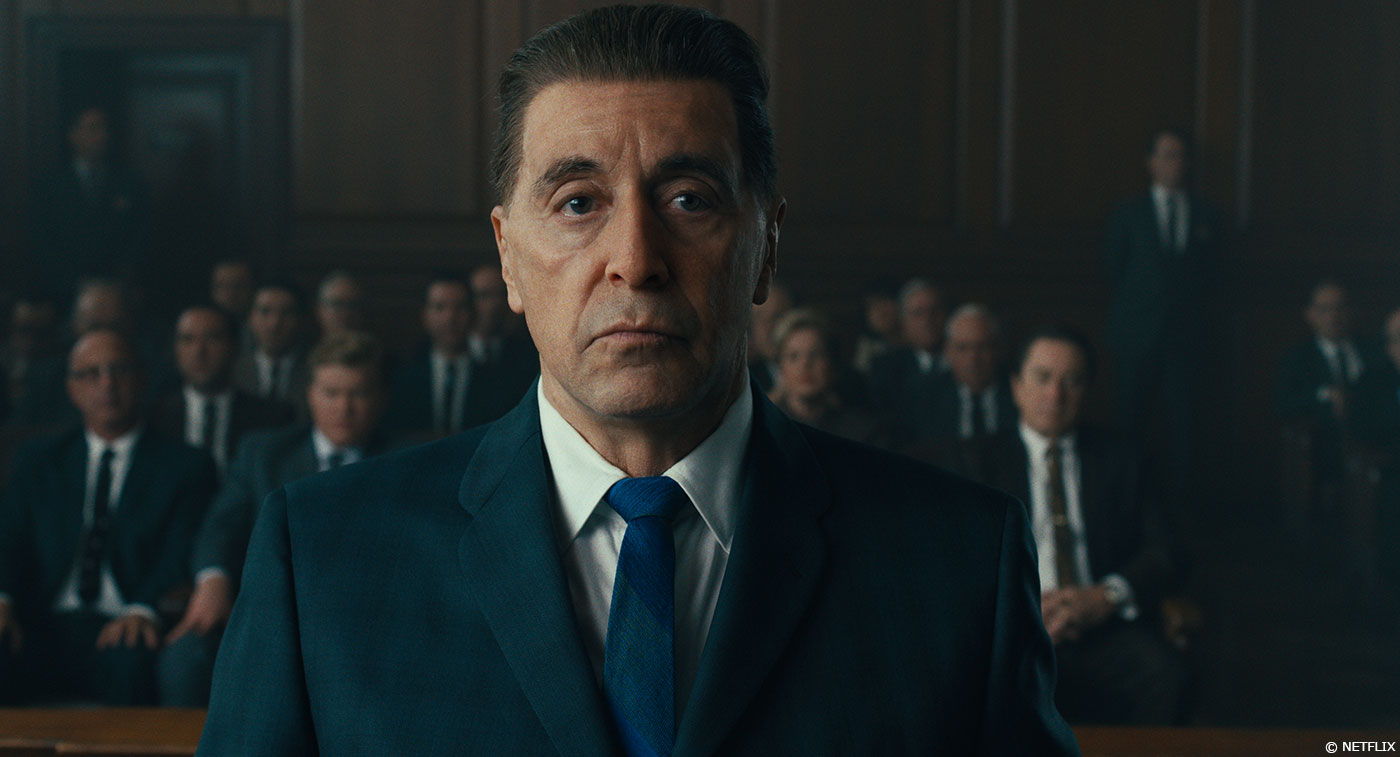

Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro had a big say in how the visual effects work was approached but also the final look of the characters. Scorsese designed these characters to be new creations rather than re-creations. He wanted to see younger versions of Frank Sheeran, Russell Bufalino and Jimmy Hoffa rather than younger versions of Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and Al Pacino. He also wanted the audience to understand where the characters came from and to further a connection to the characters throughout the narrative of the film.

Leandro Estebecoena // Scorsese has a very particular approach to filmmaking. He shoots with the whole movie in his mind, and the precision required in the performances was beyond anything I’ve dealt with in the past 20 years. I was also surprised to see how few omits we had for a movie that is 3.5 hours in runtime. And it was interesting to see that none of the shots required reframing – His compositions are very carefully considered and what you see in the film is what Rodrigo Prieto captured.

What were his expectations and approach about the visual effects?

Pablo Helman // Scorsese and De Niro both requested the greatest amount of freedom on set. The actors preferred not to wear markers on their faces or helmet cams on their heads. They also wanted to be on the set with theatrical lighting as no separate stage shoots would be scheduled. That was going to be hard. Enter, the R&D ILM team!

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

Pablo Helman // We knew there was going to be a lot of resources dedicated to research and development, so we began with the writing of the software. The R&D team spent two years writing new software called FLUX and testing it. Because of the new software, artists were retrained to use FLUX, these artists tended to come from our Layout and Simulation teams.

What was your approach for the de-aging effects?

Pablo Helman // As I mentioned above, we developed a proprietary markerless on-set software for facial capture. Dubbed ILM FLUX it allowed our actors to be on set under theatrical lighting and did away with the need to wear markers on their faces or don helmet cams. There were no restrictions of space or camera movement for either the Director or DP, Rodrigo Prieto. This system is currently the only available system in the world to allow for markerless on-set lighting facial performance capture.

To complement the software, ILM designed a three-camera rig in collaboration with Prieto and ARRI Los Angeles, which included two high-resolution ARRI witness cameras which were modified to record only the infrared spectrum attached to and synched with the primary RED director’s camera. This system captured the facial performances from multiple angles and also threw infrared light onto the actors’ faces to neutralize unintended shadows while remaining invisible to the production camera and the actors. This process provided a full set of data of every frame of each performance and all of the on-set lighting and camera positions that would be needed later.

Leandro Estebecoena // There was a lot of work done before production started… but during production, in a nutshell:

- Capture the lighting and the set topography

- Capture the performances

- Solve the camera(s)

- Solve the performance(s)

- Recreate the light rig for the sequence

- Tweak the skin materials (beyond matching the plate) following the shot’s directions

- Render and Comp

Stephane Grabli // For approximately 500 shots, the de-aging was accomplished by rendering a fully CG face of a younger version of the actor, composited over the plate. For these shots, one of the main challenges consisted in faithfully capturing the facial performance of the present-day actor, without the assistance of head-mounted cameras or markers, and transfer it to a younger-looking 3D model of that actor created by Digital Character Model Supervisor, Paul Giacoppo, and our digital model team.

Nelson Sepulveda // Digitally shot plates were prepped and modified to match film stocks 5207 and 5219. Face and body features not directly covered by the face render such as the neck, ears, chin, and shirt collar needed to be painted, removed, and/or warped to prep for render integration. Integration of full CG render. Wig/make up clean up was also needed for integration of CG renders. Bodies we modified in 2D as part of the overall de-aging process.

Ivan Busquets // There were a few different approaches depending on the age of the characters in each scene. For some of the latter scenes where the characters are in their 60’s or older, a 2D “digital makeup” approach worked best, as we didn’t need to alter the bone structure or the shape of the facial features significantly.

For everything else, full CG renders with FLUX-solved performances were necessary. On any given shot we would have to be careful to trace the right line between being accurate to the original performance, maintaining the likeness of the characters, and making them look the right age. Performance was always the main driving force, though, and the one thing that Martin Scorsese looked for on each review. So throughout all the different stages of shot production, we would constantly check what could be done to maintain the spirit and intent of the original performance.

Can you elaborate on the initial test that you presented to Martin Scorsese during Silence?

Pablo Helman // We proposed a test with Robert De Niro to make sure we were all trusting of the methodology and approach. For the test, De Niro reenacted a scene from GOODFELLAS. It was important that we “anchored” the test onto something that we were all familiar with. So De Niro, at 74 years old, recreated the famous “Pink Cadillac” scene. And in a matter of weeks we showed the test to Scorsese and De Niro. We made the 74 year old De Niro look mid-40’s. It was a key element that helped greenlight the movie.

Can you explain step-by-step about the creation of these effects?

Stephane Grabli // In pre-production, we create a present-day facial rig for each actor, leveraging the DRS’ Medusa capture system. We also capture accurate textural information using a light stage system. For each actor, a facial rig representing them at a younger age is derived from the initial one driven by our artists and their digital sculpting work. Throughout production, we preserve a one-to-one mapping between the present-day facial rig and the younger one.

On set, the performance is shot with a custom camera rig which includes two extra Infrared (IR) cameras, each mounted to one side of the director’s camera and which provides us with extra data needed to perform the facial capture in post. Additionally, for each take, we carefully measure illumination (using bracketed-exposure HDR environment capture) and, when possible the set geometry using a fast Lidar scanner.

In post, we matchmove the cameras, leverage the IR stereo data to solve for the actor’s head and construct a virtual light rig from the data captured on set. These elements, combined with the present-day actor’s facial rig are fed to ILM’s FLUX, facial performance capture solver. Leveraging texture details and shading cues, FLUX is able to solve for 3D facial rig controls which faithfully reproduce the facial expressions seen on the footage. For some shots, this geometry was further refined through a muscle simulation. The animated 3D is then passed onto our technical directors for lighting, and then it is rendered and integrated by our compositing team.

Did you use markers or dots on the actor’s faces?

Leandro Estebecoena // The ILM FLUX solver does not require markers, unlike all the other solutions out there, in which the subtle movements between the markers are usually lost before the performance is rendered. We also could not use any sort of head-mounted cameras, nor ask the actors to re-enact the performance in a separate, controlled environment after the scene was shot. The actors’ performance had to be captured on the set while they were interacting with each other (and under the uncontrolled on-set lighting)

Can you tell us more about the use of the witness cameras?

Pablo Helman // Since we did not have markers on the actors’ faces, we needed to get the greatest amount of information from the actors in front of the cameras. So having witness cameras situated to the left and right of the director’s camera allowed us to triangulate the actor’s performance and position the actor in 3D space.

Stephane Grabli // The witness cameras were ARRI Alexa Minis which were modified to be sensitive to light in the Infrared (IR) spectrum rather than in the visible spectrum. The use of these cameras was twofold: 1) To help us position accurately the CG head in space (leveraging the multiview stereo data provided by the two cameras). And 2) as redundant facial performance data: for shots with particularly challenging conditions (motion blur, hard shadows, etc), the IR footage provides dependable data to complement the solve run on the main camera footage.

Can you elaborate on the creation of the shaders and textures for the skins?

Leandro Estebecoena // We used Lightstage for the initial basic color/displacement textures. (And took hundreds of photographs as well for reference) before the shooting started. This project was a combination of artistic craft from some of our best texture artists led by supervisor Jean Bolte in collaboration with our Shaders and Look Development departments. Pore maps, micro wrinkles, in combination with blood flow, anisotropic spec, and « peach fuzz » hair (among other things) were implemented to get a proper skin look for each of the different ages for the three actors. The unprecedented level of subtle moves captured along the face also made the skin look more believable.

How did you handle the challenges of the matchmove?

Pablo Helman // First, the layout team match moved the three (and many times nine) cameras in the scene. Second, the actors’ bodies and heads were matchimated into the scene. Last, the light rig based on lidar’d scenes from the set was constructed so that the FLUX team could start the computations. The custom 3-camera rig helped the layout team immensely.

The faces are seen in various lighting conditions. How did you manage this aspect?

Pablo Helman // The use of infrared red cameras helped to get rid of shadows on the actors’ faces. Whenever we could, we worked with our DP, Rodrigo Prieto, to get as many LED light sources as possible as opposed to incandescent sources. That is because incandescent light contaminates the infrared camera intake. While much of the time it wasn’t possible, occasionally he could accommodate our request.

Stephane Grabli // Regarding the capture, it was important to carefully measure illumination on set so that we could faithfully reproduce the lighting digitally. The facial solver uses lighting as a source of information, so as long as we have an accurate virtual light rig, the variety in lighting conditions does not typically pose a particular challenge. For shots with very hard shadows, it was generally difficult to reproduce the illumination conditions with perfect accuracy so it was up to our skilled artists to create the seamless match.

What were the first reactions of the cast when they saw their younger versions?

Pablo Helman // De Niro said, “You gave me 30 more years in my career!”. Pesci and Pacino both smiled.

Leandro Estebecoena // It was great to see Martin Scorsese and the cast’s excitement after seeing our first tests and we were immensely gratified when they saw the final film and gave the crew fantastic feedback.

How did you choose the various VFX vendors?

Pablo Helman // Screen Scene (SSVFX) showed us some great de-aging tests they had done. That assured me that they were serious about getting this right. Same with Vitality, they did some tests for us and they showed the quality of the work was paramount. And both teams did great work on the show.

How did you split the work amongst these vendors?

Pablo Helman // SSVFX did extensive 2D period work and matte paintings and also de-age work on Al Pacino at age 60-62-year-old. Additional 2D work on Pacino and work on the de-aging of the hands was performed by Vitality in Vancouver.

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

Leandro Estebecoena // Early in the show, we worked on a shot in which the camera orbits around Robert De Niro (while he speaks to Hoffa for the first time over the phone) which we considered the most difficult, so we dive into it under the belief that if we could do that one, the rest would be easier. But as we dive into production, and the focus changed from the static assets looks more towards the performances, more challenging shots appeared that made the shot easier in comparison. One that comes to mind is the shot right after De Niro says to Harvey Keitel and Joe Pesci that he was « blowing up a laundry place » at the beginning of the shot, De Niro pauses for a second and looks at both. We thought we had that performance nailed but when we showed to Martin Scorsese he rejected it stating that it was too aggressive and it should be more into the « defensive » realm. The level of subtlety we went after to deliver these shots was unprecedented.

I don’t remember easy shots on this one – In fact, the conditions on most of the shots were « merciless » for digital asset work. I am talking about very long, brightly lit, close up shots, with either a very still camera or, in cases where the camera was moving, it was revolving slowly around the actor. (i.e. No « action » shots to hide behind motion blur.)

Stephane Grabli // A few shots were challenging capture-wise because of the difficulty reproducing lighting or because the expressions were particularly hard to hit for the solver. And some of the shots where he looks the youngest were challenging, not so much because of the capture (these actually worked well from that standpoint) but because retargeting would not immediately hit the right age and would require extra modeling or comp work.

Ivan Busquets // I recall one particular shot where Frank gets out of the car and threatens Deadbeat with a gun concealed in a paper bag. This was a long shot, with more extreme (anger) expressions on Frank than what we see elsewhere in the movie, and I remember it was a challenge to dial those in. In the original performance, his neck flares out in anger, so we had to find the right interpretation for a young version of that neck, too. Shots on the other end of the spectrum (very subtle performances) were challenging as well. De Niro’s performances were masterfully subtle, sometimes conveying an emotion with just a bit of chin movement, or minute eye adjustments. When rendering the young asset on those types of shots, we had to be extra careful to retain all of those details.

Did you want to reveal any other invisible effects?

Pablo Helman // Besides de-aging there were several very difficult shots that connect real world locations with sets. For instance, for the murder at Umbertos Clam House we transition from a NYC location to an interior set-piece of the restaurant. Another example is the Barber Shop murder where we transition from a barbershop set to the Roosevelt Hotel location. There were also contributions from the Special Effects team including taxis being rolled into the river, car/misc explosions, boat explosion and extensive period work to make the different cities in the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s.

Nelson Sepulveda // There was significant period work done. Building and street modifications. Removal of all modern street features, buildings and added period elements (traffic signs, street light, billboards etc.) Make-up and wig fixes in areas connecting to the digital work. And makeup fixes when they are in their eldest form.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

Pablo Helman // All of it stops me from sleeping at night. But our team is great and we rely on each other and I have great faith in the ILM process. We’ve known each other for a long, long time. So there is no room for failure.

Leandro Estebecoena // The « merciless » shots conditions for digital human work allowing for a long time for scrutinization. Very long, well lit, closeup shots with either a relatively motionless camera or, if the camera was moving, it was revolving slowly around the actor. (i.e. No « action » shots to hide behind or motion blur to conceal any detail.)

The « unknowns » at the beginning of a groundbreaking project like this. But despite crossing uncharted territory, we managed to deliver a solid, and in my opinion, seamless result.

Stephane Grabli // At the beginning of pre-production, I had a few sleepless nights. Like the first time we tried running FLUX on test footage we shot (that was back in early 2017), the system in its early beta stage completely failed. Thankfully, we were able to improve it and move forward. And generally speaking, this was a production where the tech was constantly evolving while shots were being run by artists – not always a comfortable situation to be in. Ultimately, I was lucky to work with a small team of very strong engineers to get the software completed and also a larger team of very talented artists who could put up with the lack of polish in the early versions of FLUX.

Nelson Sepulveda // For me it was knowing we had to be able to make every composite 100% believable. Also, translating each and every micro expression made by an actor in their 70’s and make the same expression believable in a younger face.

Ivan Busquets // The need for making compelling, believable digital human characters to a level where they can seamlessly blend in a dramatic story like this. There was no room for failure here. Our work couldn’t look “CG”, or it would take the audience out of the story. That’s enough to steal a few hours of sleep from anyone!

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Leandro Estebecoena // It’s difficult to pick a single one, but the extreme closeup shots of Hoffa in the courtroom, the closeups of Pacino and De Niro when they talk over the phone for the first time, and the first shot in which we see Hoffa comes to mind.

Stephane Grabli // The sequence where Frank describes how Russel operates, from the Penn drapes and Curtains storefront. You have two long splendid tracking shots (following Russel in the store first and then following mob guys in the barber shop) and one dolly shot where Russel directly addresses the audience. These are incredibly satisfying shots.

What is your best memory of this show?

Leandro Estebecoena // There are lots of really great memories but the one that comes to mind is seeing Martin Scorsese very happy (swearing-in excitement) after seeing our work’s initial tests/takes.

Nelson Sepulveda // Hands down, Pablo having to run to the restroom mid-review. I’m telling that one to the grand kids.

Stephane Grabli // When I realized back in 2017 after an extensive series of tests, that the capture methodology we had developed could actually work.

Ivan Busquets // Shot reviews with Scorsese, Pablo, and the film’s editor, Thelma Schoonmaker – Each one was a true masterclass in filmmaking.

How long have you worked on this show?

Pablo Helman // I have worked on the show since 2015… 4 years! But it was worth it.

Leandro Estebecoena // After 4 years on this one, this is the longest I’ve been involved in a show (the previous one was RANGO at 2.5 years). I am really proud to have been given the opportunity of helping on this one from the beginning – since the « How the heck we are going to do this? » early days til now hearing people asking « How you guys did that? »

Nelson Sepulveda // 17 months 1750 + shots. The difficulty of this project was as high as it gets. Arguably , it’s the most difficult task of my career and also the most rewarding.

Stephane Grabli // I was on THE IRISHMAN from November 2015 until we wrapped postproduction. It may seem like a long time but it was barely enough time to realize the ambitious R&D vision of this project. I’m so very grateful that we had that amount of pre-production time, it was instrumental in getting things done right

Ivan Busquets // 15 months. June 2018 to August 2019, and about 350 3D shots executed in ILM’s Vancouver studio. The work was very challenging, but we were fortunate to have extremely talented artists all around. Seeing how integral the visual effects work is to the storytelling has been the best reward.

What’s the VFX shots count?

Pablo Helman // 1750 VFX shots in the movie or 2 ½ hours of running visual effects footage.

What was the size of your team?

Pablo Helman // We had 500 artists in ILM’s San Francisco and Vancouver studios.

Stephane Grabli // For Flux: At the peak there were 38 FLUX artists and the FLUX R&D team scaled from 1 to 5 engineers at the peak of production.

What is your next project?

Pablo Helman // Sleep…

Leandro Estebecoena // Vacation! Well… actually – Helping a bit on THE MANDALORIAN first.

Stephane Grabli // Keep on improving ILM’s FLUX system.

Ivan Busquets // Getting some rest, then switching gears to work on a horror movie!

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Industrial Light & Magic: Dedicated page about THE IRISHMAN on ILM website.

Netflix: You can now watch THE IRISHMAN on Netflix now!

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2019