Alexander Seaman started his career in visual effects in 2004 at MPC, he then worked at Framestore before joining DNEG in 2006. He has worked on various films such as 2012, Furious 6, Zack Snyder’s Justice League and Venom: Let There Be Carnage.

Mike Duffy has worked in post-production for over 17 years. He worked at Mr. X, Spin VFX and Framestore before joining DNEG in 2020. He has worked on projects such as John Wick, Suicide Squad, Fargo and Jingle Jangle: A Christmas Journey.

How did you and DNEG get involved on this show?

Alexander: Netflix approached DNEG with a large amount of work that needed to be done in a short time. DNEG had the appetite and capacity to be able to undertake these types of projects, so we quickly got to work. We had also done science fiction projects before, so knew that The Adam Project would fit the scope of our talent pool really well. We also had a great relationship with VFX Supervisor, Alessandro Ongaro; I had worked with him before on films such as Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, as well working on a few superhero/science fiction movies myself in the past, so overall the project seemed like a good fit for us all.

Mike: The Adam Project had a very tight timeline, and required us to move at full speed right away. In August, we received confirmation about which sequences we were going to be working on, and then a few days later had a call with the VFX Supervisor and client supervisor. It was a very fast, quick-moving project.

How was the collaboration with Director Shawn Levy and Production VFX Supervisor Alessandro Ongaro?

Alexander: We collaborated predominantly with Alessandro and it was excellent; we had a very similar shorthand for understanding what the briefs were and what the energy of the film was. We got Director Shawn Levy’s rough cut of the movie with some rough sound and music scores, and it gave us a really good sense of the flavour of the movie right from the offset. It was very easy to understand the creative decisions of the movie based on the references we had been given right from the very start of the project.

What are the sequences made by DNEG?

Alexander: DNEG worked on a variety of sequences, but was mainly responsible for the Sorian jet, the time jet, and the wormhole. We worked on the opening sequence with the chase through outer space before Adam disappears into the wormhole; the scene in the forest where young Adam discovers the jet and its invisibility effect; a few sequences where the jet was parked within the forest (lots of set extensions and CG jets and trees); a big chase where the bad guys in the Sorian jet are pursuing the heroes in an SUV through the forest; a big sequence where the two jets are having a dogfight or chase through the canyons, mountains and above the clouds; and the fight scene in the backyard.

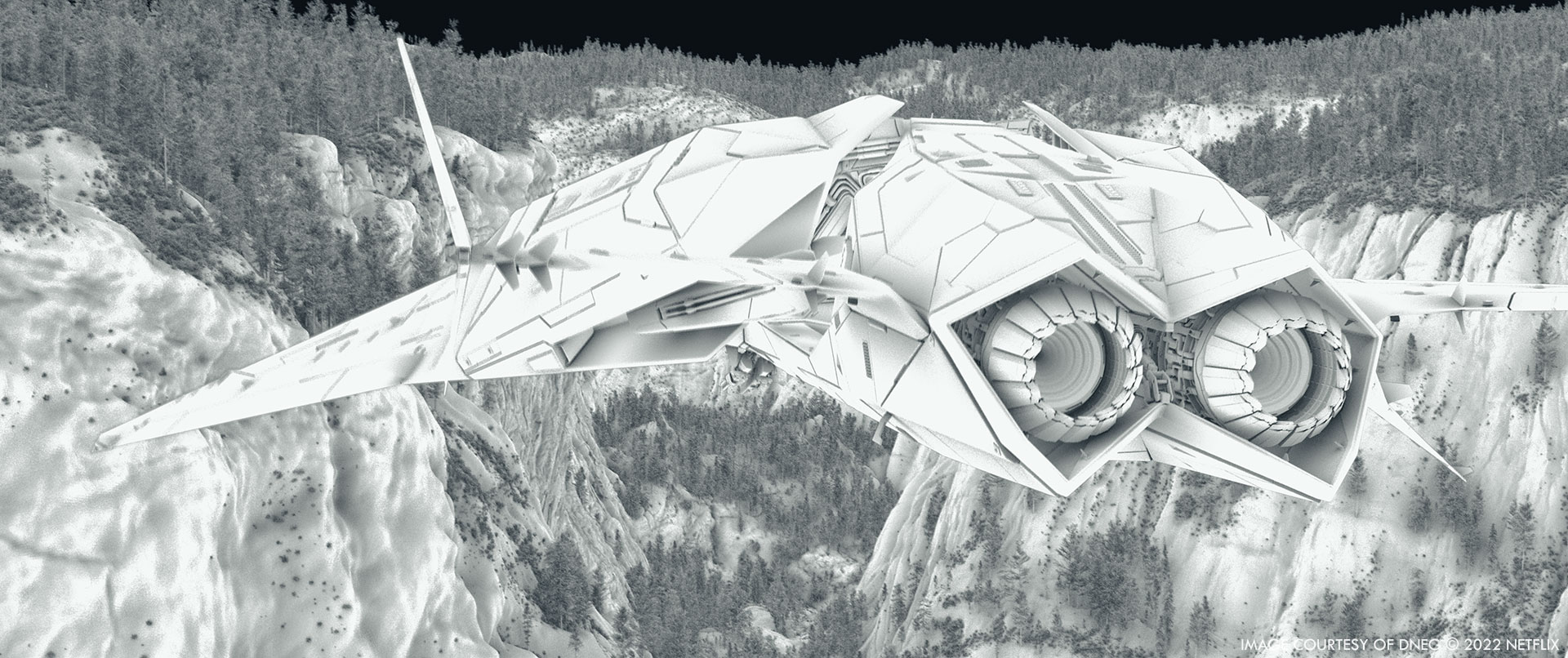

Can you elaborate about the jet’s design and creation?

Alexander: The jets were only meant to be designed slightly in the future, so we didn’t want to go too science fantasy. They had to be believable. We therefore referenced cutting edge military designs and stealth designs from all around the world and picked up ideas and inspiration from these real life objects. We then integrated them with the brief of the two real life jets. The brief of the time jet was a very fast, supersonic, nimble military vehicle. The Sorian jet was supposed to be the equivalent of a big dark tank–capable of fast flying, but with a little bit more of a sinister, ominous presence to it.

How did you create the various shaders and textures?

Alexander: We used a lot of in-house tools to create the various shaders and textures. We rendered them through Clarisse, which is our current show-renderer. We referenced real-world materials for all the textures–paint insignias, lights etc–which were then passed through a fairly standard shading tool set in order to render them the way they were presented in the film.

Mike: The Sorian time jet also accrues more and more damage throughout the film, so there were quite a few different instances of textures that needed to be developed for those story points.

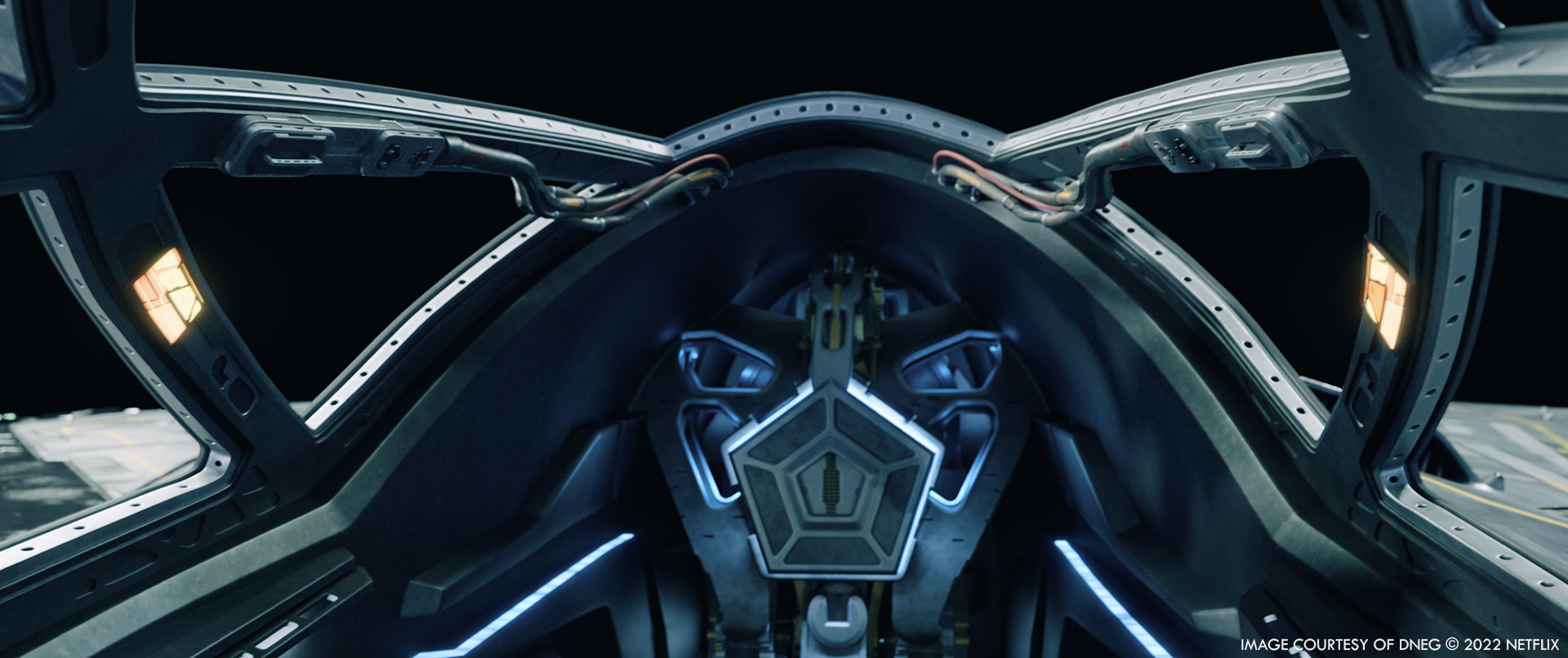

How were the shots filmed inside the cockpit?

Alexander: They were shot on a blue screen sound stage. All of the cockpit shots were shot on a motion base on a sound stage. Ryan Reynolds then sat inside it with his flight suit against a blue screen set. He was also put on a gimbal, which meant they [the filmmakers] had a certain amount of control over the amount of tilt or rumble that he experienced at any point. Then we digitally replaced the backgrounds, as well as large portions of the interior cockpit, so that it looked a little bit more science fiction-like than the original set designs.

Can you tell us more about the jets animation?

Alexander: The jet’s animation had to be believable, even though it was moving at a speed too fast to be realistic. We had to come up with numerous panels and rudders and be able to articulate them as much as possible so that it looked like a believable, fast-moving jet. One of the creative problems we faced was how to give the jet a sense of speed and danger in an outer space environment. To give the impression of a fast moving aircraft, there shouldn’t be a lot of movement in the panels and rudders, but we had to accentuate that in order to give it a sense of danger and excitement. We also added vibrations to the flutters and any moving parts in the aircraft in order to create this sense of energy.

Mike: There were also a few additional animation gags up on the aircraft, such as weapons being deployed and the time canon. We had to come up with a few different rigs with a few different scenarios and work out how to fit weapons, guns and landing platforms into the aircraft as well.

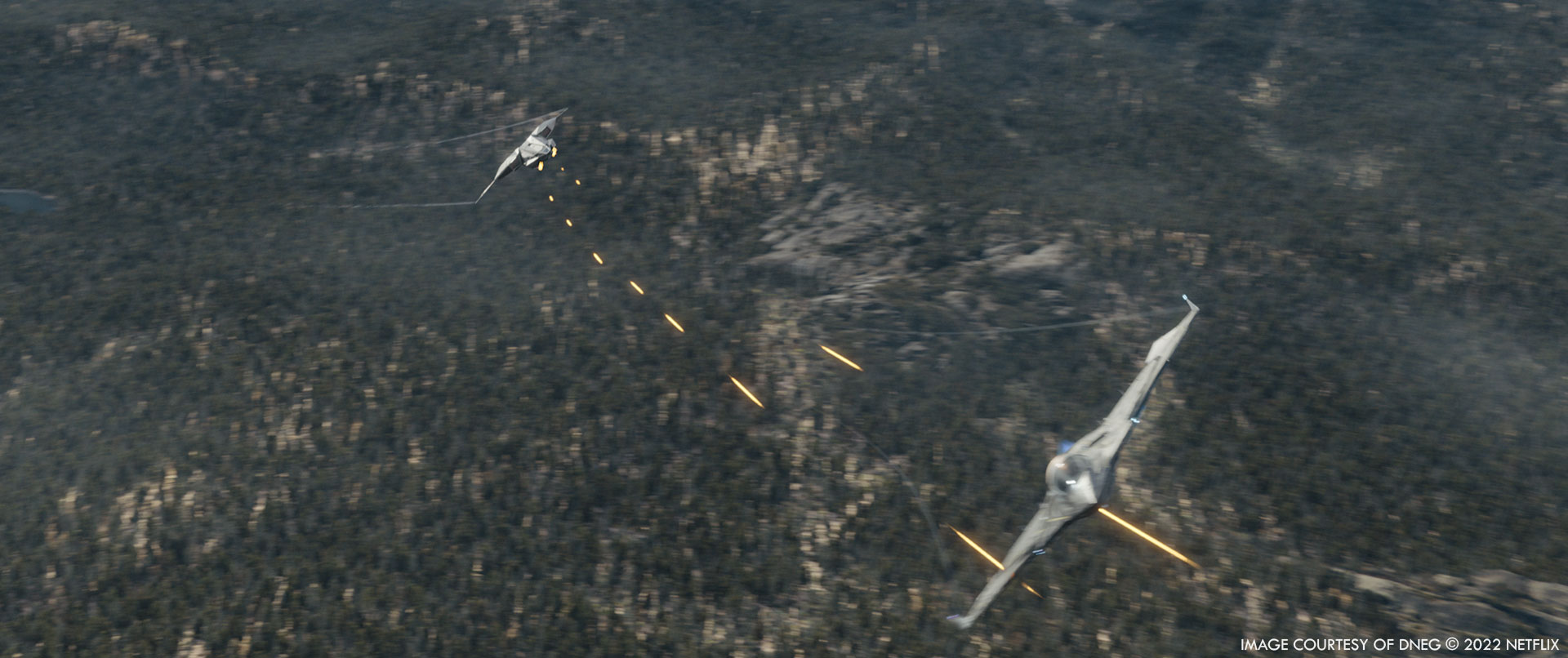

How were the dogfight sequences choreographed?

Alexander: The creation of the dogfight sequences was a fairly intricate process. There were a few rounds of pre-visualisation that were done, and they had also filmed some aerial footage and plates of mountains from above the clouds in North America. We then picked up the pre-visualisation and the aerial footage and tried to repurpose it to create the same camera angles and speeds. Where this wasn’t possible we had to digitally create an environment–a digital valley, a digital rock surface, a digital cave. We would then block all of that out and animate the chase. We would assess whether the scene was exciting or fast enough, and then augment each individual shot accordingly. In some instances, the aerial footage wasn’t high or fast enough, so we looked for methods of re-speeding plates we already had or replacing it with a CG version of the same thing from a different perspective.

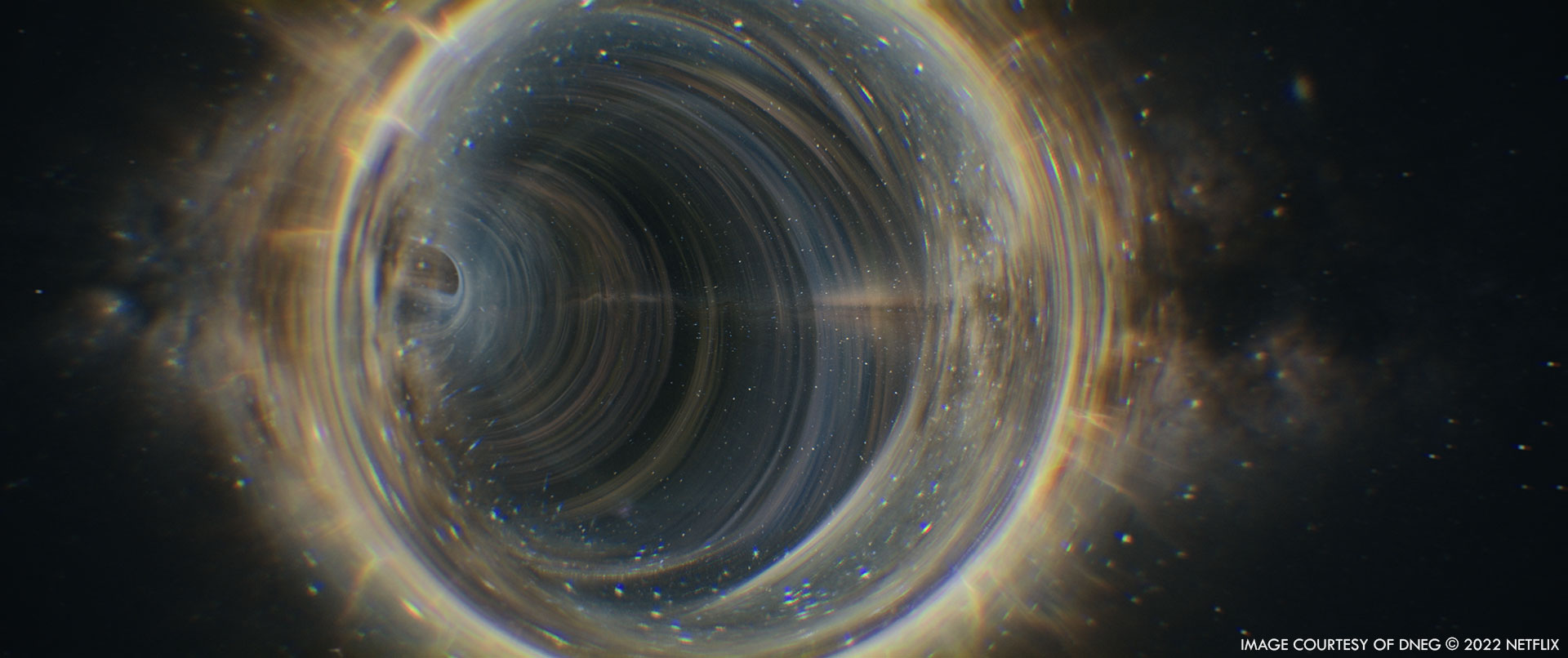

Can you explain in detail about the creation and animation of the wormhole?

Alexander: One of the key creative challenges of the film was figuring out the unique design of the wormhole, which had to disappear after the jet flew through it. Some of the references that Director Shawn Levy had been guiding us towards was optical flares and lens distortions. We used these as a basis for coming up with lens-based tricks or lens-based ways of representing a space. We looked at the way that different prisms behaved, and then ultimately determined that the wormhole needed to have some kind of funnel in the middle of it where the ship could disappear down. The creation and animation of the wormhole was actually a fairly simple 3D task with some fairly rudimentary 3D volumes and shapes which could be easily animated to be scaled up and down, but the composite of it was the most challenging aspect as well as the simulations that we emitted from the surfaces of the volumes. For instance, we had to think about what we could see behind the wormhole, and what we could see through it. In one instance, you get to see where the ship is going to be traveling to, so we used photography and distorted that through various lenses at various different times.

Mike: The main conceptual part of the movie was the wormhole. Each time a movie does something like that you want to be careful not to copy what has already been done. DNEG has a great history of doing wormholes and black holes for movies, so we had the tricky task of creating something unique that had not been done before.

How did you create the forest environment for the car chase?

Alexander: There was a real forest which had various different types of pine trees and vegetation, as well as a dirt road running through the middle of it. In order to make the sequence more exciting, they wanted to completely replace the dirt road and instead have the jeep moving to and fro between various bushes. We used the onset reference for what the trees and plants looked like and had a very talented modeling team recreate the same vegetation that we saw in the forest. We also had a very good environment team effectively fill in the forest for the pieces that were missing.

Which shot or sequence was the most challenging?

Alexander: The most challenging shot was probably the wormhole opening up in space. Here the camera starts on the time jet firing the cannon, which births the wormhole, and then does a huge move to not only see the wormhole being created but also going behind it. We are then shown the earth and the aircraft chase being distorted through the back of the wormhole. We had to cram a lot of different characteristics and visual effect styles into one shot while also making it exciting. The most challenging sequence was the dogfight through the canyons. We not only had to choreograph an exciting aircraft chase through the canyons, but also believably recreate a canyon digitally and make it look photo-realistic.

Mike: We had to be aware of continuity as we were doing a lot of the backgrounds ourselves. It was also quite difficult to keep track of and manage the increasing damage of the time jet throughout the film as well.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Alexander: The aircraft chase through the canyons.

Mike: The forest chase.

What is your best memory on this show?

Alexander: Besides from the birth of my son, we had a great moment from the feedback of a director screening of the project where we received gasps and applause from the filmmakers about how believable the canyon sequence appeared.

Mike: The show had begun with a different studio and there were a lot of nerves that the show couldn’t be completed in such a short space of time. My favourite part was witnessing the filmmakers’ excitement when they began to see that we were going to deliver their movie on time and to an incredibly high standard. To be able to put such an A-list team together and deliver that standard of work in such a short time-frame is quite rare.

How long have you worked on this show?

Around 6 months in total.

What was the size of your team?

Alexander: The work was split between sites in London, India and Montreal with a team of around 200-300, but the project was definitely a London driven show.

Mike: Yes, London did the shots that required conceptualisation as well as the most difficult sequences.

What is your next project?

Alexander: Something very different with no time travel or wormholes.

Mike: Something very different, but I can’t say any more than that.

A big thanks for your time.

// Behind the Scenes of The Adam Project | Netflix

// Behind the VFX of The Adam Project | Netflix

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

DNEG: Dedicated page about The Adam Project on DNEG website.

Alessandro Ongaro: Here is my interview of Alessandro Ongaro, Production VFX Supervisor.

Netflix: You can watch The Adam Project on Netflix.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2022