In 2019, Kevin Baillie explained to us the visual effects work on Welcome to Marwen. He then worked on Men in Black: International and The Witches. Today he talks to us about his new collaboration with director Robert Zemeckis.

What was your feeling to work again with Director Robert Zemeckis?

We’ve been working together for over 15 years now, so I guess one word to describe the feeling could be “familiar.” 🙂 Seriously, though every project is so different that we always have unique problems to solve. So, while the working relationship feels familiar, the challenges we tackle always feel fresh and exciting!

That’s your 7th movie with him. Can you tell us more about this long collaboration?

I feel like every project we work on together is another opportunity for me to learn from him and, on the flip side, I get to repay his trust with contributions that are ever more effortlessly matched with his vision. I feel like a large portion of the VFX Supervisor job is exactly that: to learn the Director’s personality and tastes so that one can anticipate their needs.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

VFX Producer Sandra Scott and I have been working together for nearly 15 years, so we obviously enjoy working together! Put simply, she handles schedule, budget and logistics and I handle the creative and technical aspects of the project. In reality, however, the split of work is not that clean. She regularly gives me creative feedback and ideas, and I weigh in on schedule and budget. It’s an 80/20 split for both of us, I’d say, and it feels like a great way to support one another.

How did you choose the vendors?

During prep and the shoot, we made extensive use of Virtual Production and needed expertise in four main areas: animation, assets/environments, shooting virtual cameras and on-set LED Walls and Simulcam. We searched far and wide, talking to many companies and trusted friends in the industry, and ended up with a blend of vendors; one to tackle each area.

Mold 3D, led by Edward Quintero, served as our Virtual Art Department (VAD), building environments in conjunction with our Production Designers Doug Chiang and Stefan Decant. A small team of MPC’s lead animators, helmed by Christophe Paradis, animated the real-time characters. Casey Pike’s team at Halon assembled it all together, and Kristen Turnipseed ran our virtual camera stage, serving as BobZ’s camera team for virtual camera shoots. Dimension Studio ran the on-set components, with Jim Geduldick, Steve Jelly and Callum Macmillan leading the charge there.

It sounds like a lot having four vendors involved in the one process of the film but, thanks to an open and collaborative attitude from all of them, it worked out extremely well! In fact, most of the time it felt more like one team working together than 4 separate companies!

For post, MPC was the sole VFX vendor on the film, and earned that spot by having delivered successful project after successful project for Disney, from The Jungle Book to The Lion King.

How was the collaboration with their Animation and VFX Supervisors?

I really enjoyed working with them all!

Animation Supervisor Christophe Paradis and his right hand Kaveh Ruintan were an absolute joy to work with every single day. They brought such a fun creative energy to the project, and were great partners in exchanging ideas and discussing how to bring attitude to the digital characters and generally improve shots.

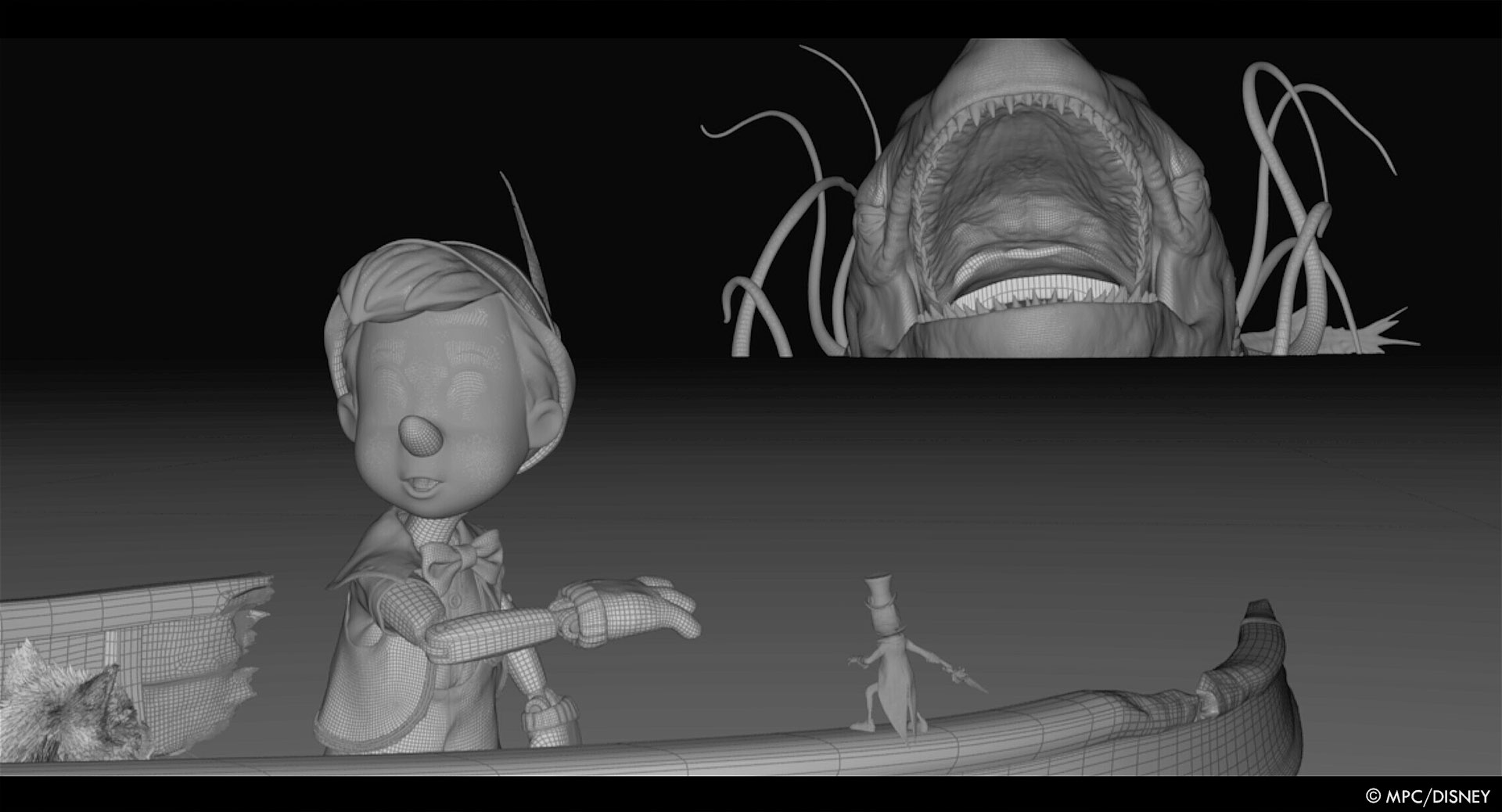

VFX Supervisor Ben Jones has been with MPC for a long time, and really knows how to get the best out of the team there. His attention to detail and technical know-how was critical in elevating the assets and shots to the next level. My mind was particularly blown by the work that he did with the character team, led by Giles Davies, did on the film. You could literally put a camera inside of Honest John’s mouth and it’d hold up at 4K! Ben also covered VFX Supervision on Main Unit for the days when I was Directing 2nd Unit, which I greatly appreciated!

Can you elaborates about the Virtual Production process on this show?

We used almost every tool in the Virtual Production toolkit for Pinocchio, and our incredible Virtual Production Supervisor John Root was critical in holding it all together (which was no small feat!). We started by Mold3D building virtual environments in Unreal, using them to scout the set builds and iterate on their designs with BobZ and our Production Designers. From there, MPC’s pre-pro animation team (we called them “The Brain Trust”) animated every scene action to cut, as if acting out a stage play, based on scratch dialogue tracks and Bob’s blocking direction. Halon would assemble the animation into the environments, tweak lighting, and get it ready to shoot in.

BobZ would then shoot every scene with a virtual camera as if he was filming the real movie. Those setups would get rendered out and sent to editorial, as if we were sending live action dailies to the cutting room. From there, our picture editor Jesse Goldsmith cut together a previs version of the entire movie, which Bob had shot and directed himself. This all happened before a single nail had been hammered into a real set!

Not only did this early version of the film serve as a sandbox for Bob to experiment in, it served as an incredibly informative communication device with the heads of all of the live action departments, from production assigned to our cinematographer, to our music composer Alan Silvestri.

Working with Dimension, we repurposed the real-time assets we’d build for the virtual camera/previs sessions for out-of-view LED walls for the Pleasure Island scenes, where large LED walls were used for lighting and reflection. By keeping the background behind the live-action bluescreen, we were able to retain full flexibility in terms of the final comp while also getting all of the great lighting benefits of LED Walls!

We also used simulcam to visualize set extensions in real time on set, which allowed the camera team to compose for something far more informative than a bluescreen void! 🙂

How did you work with the art department to design Pinocchio and the various characters?

Doug Chiang and his team designed the characters for the film, starting our with beautiful concept art and quickly progressing to rough 3D models. We used those models generated by the art department to inform builds of our final 3D models.

Can you elaborates about the creation of Pinocchio, Jiminy Cricket and the others?

For Pinocchio, we knew we would need to have a physical version of him for the beginning of the film before he comes to life, so MPC built an extremely detailed model of him based on the art department model and concept art. Dave Asling from Creation Consultants used that final model to CNC a physical Pinocchio head and all of his body pieces out of solid blocks of wood.

It’s impossible to tell what the wood grain structure inside of a wood block will look like, so it took many attempts at milling Pinocchio’s head before arriving at one that we all loved. So, in the end, there is truly only one “hero” Pinocchio head in existence!

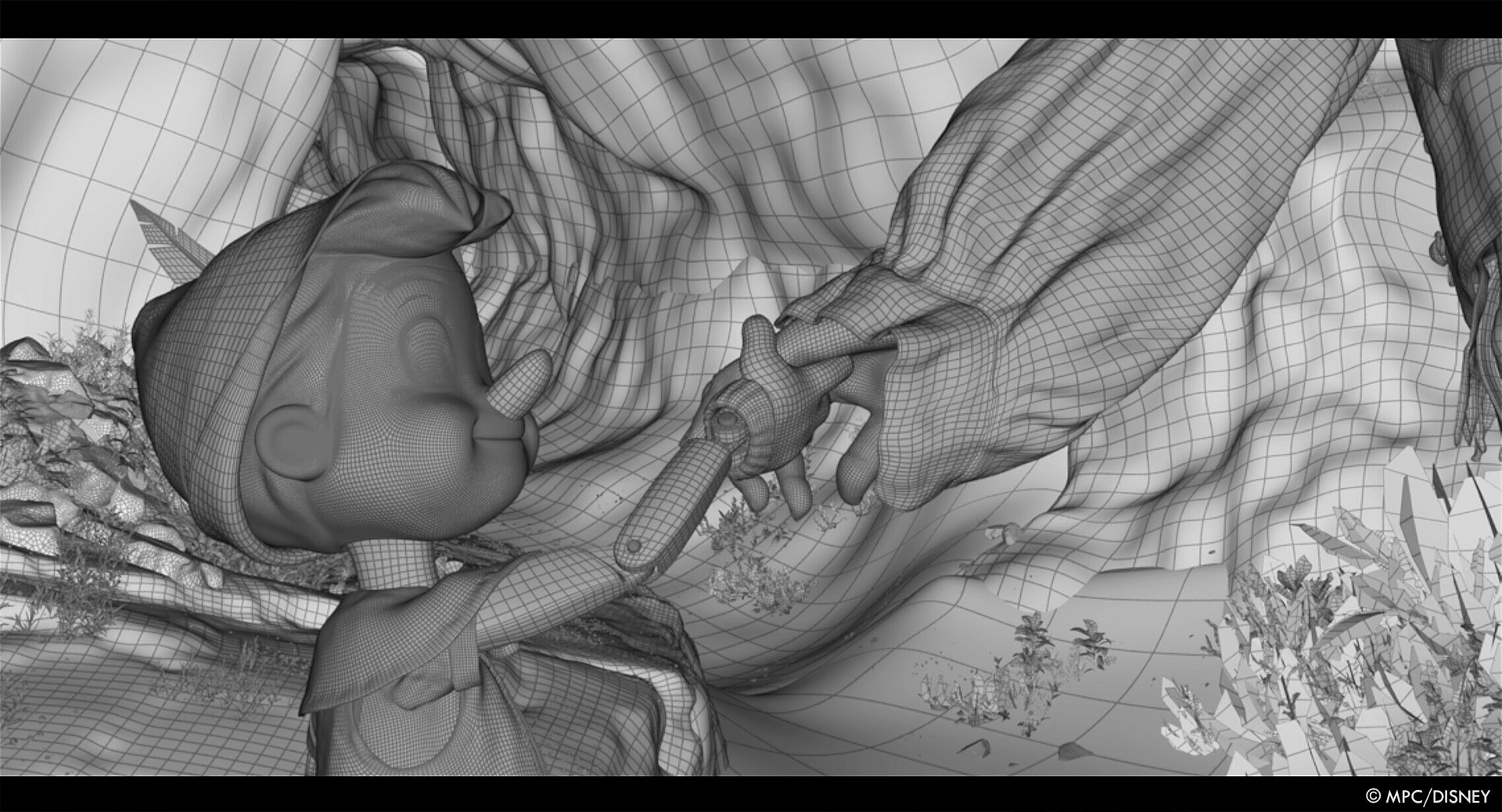

Once the physical puppet was built, Joanna Johnston and her team costumed him. We scanned the finished result and round-tripped it back into our digital build at MPC, so that the digital version of Pinocchio looked exactly like his physical counterpart. It was a really cool example of the digital and physical parts of the process collaborating!

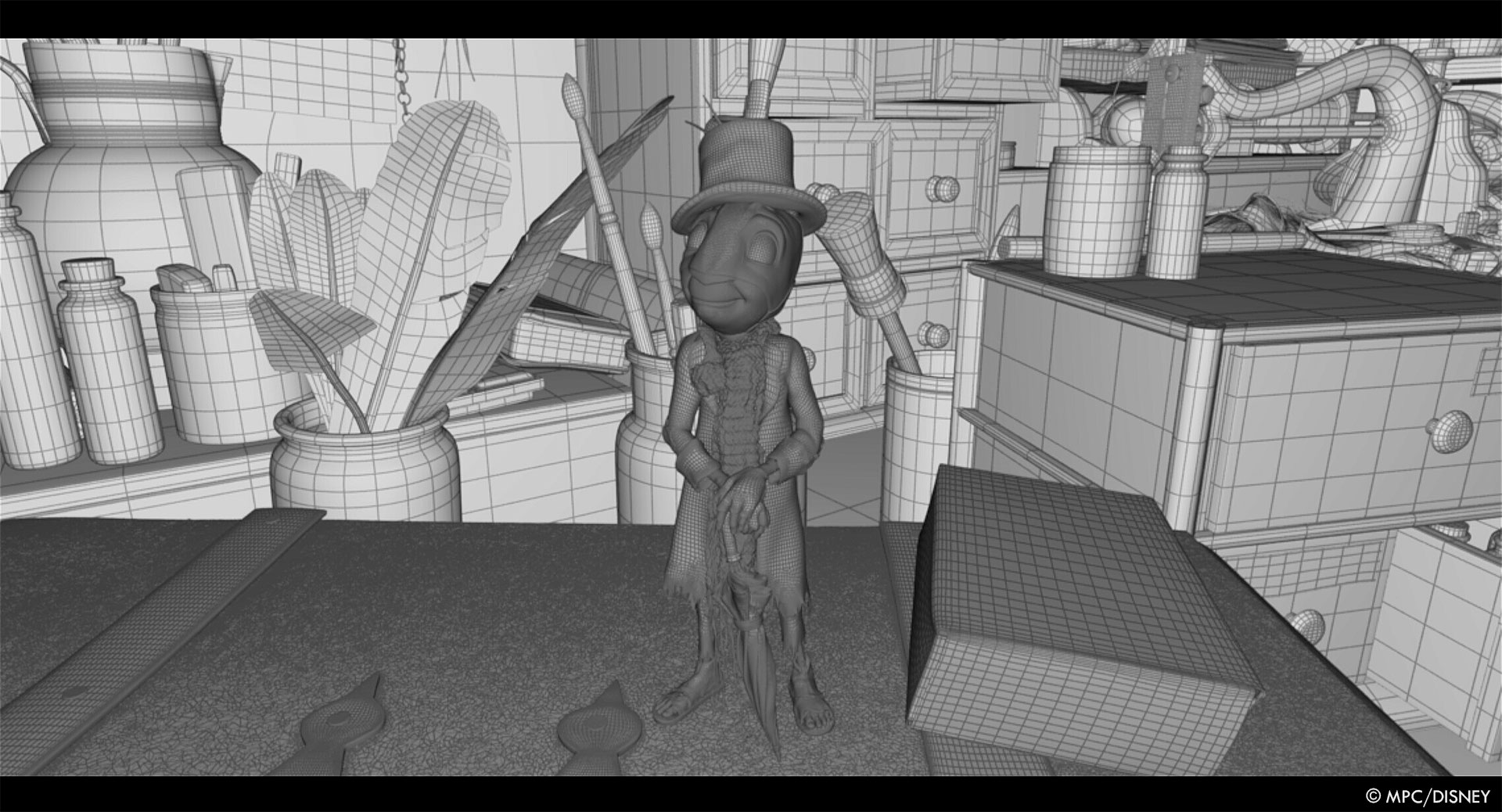

Jimmy Cricket, Honest John the fox and Gideon the cat were all designed as concept art, built as rough 3D models, and 3D printed out life-size so that Joanna and her team could costume them for real. These costumes were both scanned and physically sent to MPC for motion and texture reference.

All of the physical builds for characters, even if they never show up in a live-action scene, really helped to ground them with a physical look.

Can you tell us more about the rigging and animation?

Ben, Giles, Christophe, Kaveh all guided MPCs talented rigging ream to rig the characters. There were some complicated considerations, like cloth-on-fur interaction for Gideon and Honest John.

The most complicated thing was probably Pinocchio’s face, which is obviously covered in wood grain. If the grain moved perfectly with his face, he would look like rubber. If it didn’t move it all, it would look like an error. The character development team devised a solution by which they could paint weight maps that defined how much the wood grain would follow the movement of the face. In some areas, it stuck perfectly to his topology. In other areas, like around the eyes and eyebrows, it didn’t move at all. This helped to avoid the rubbery look while also keeping the results instinctively relatable. At the end of the day, I don’t think the audience will even notice what we did!

What kind of references and indications did you received for the animation?

The animators were inspired, of course, by the voice performances for our actors first and foremost. And, in some instances, they would reference the video from the voice recording sessions. From that point, the animators would shoot reference video of themselves acting out the body movements of all of the performances, which would then inform keyframe animation of all of the characters.

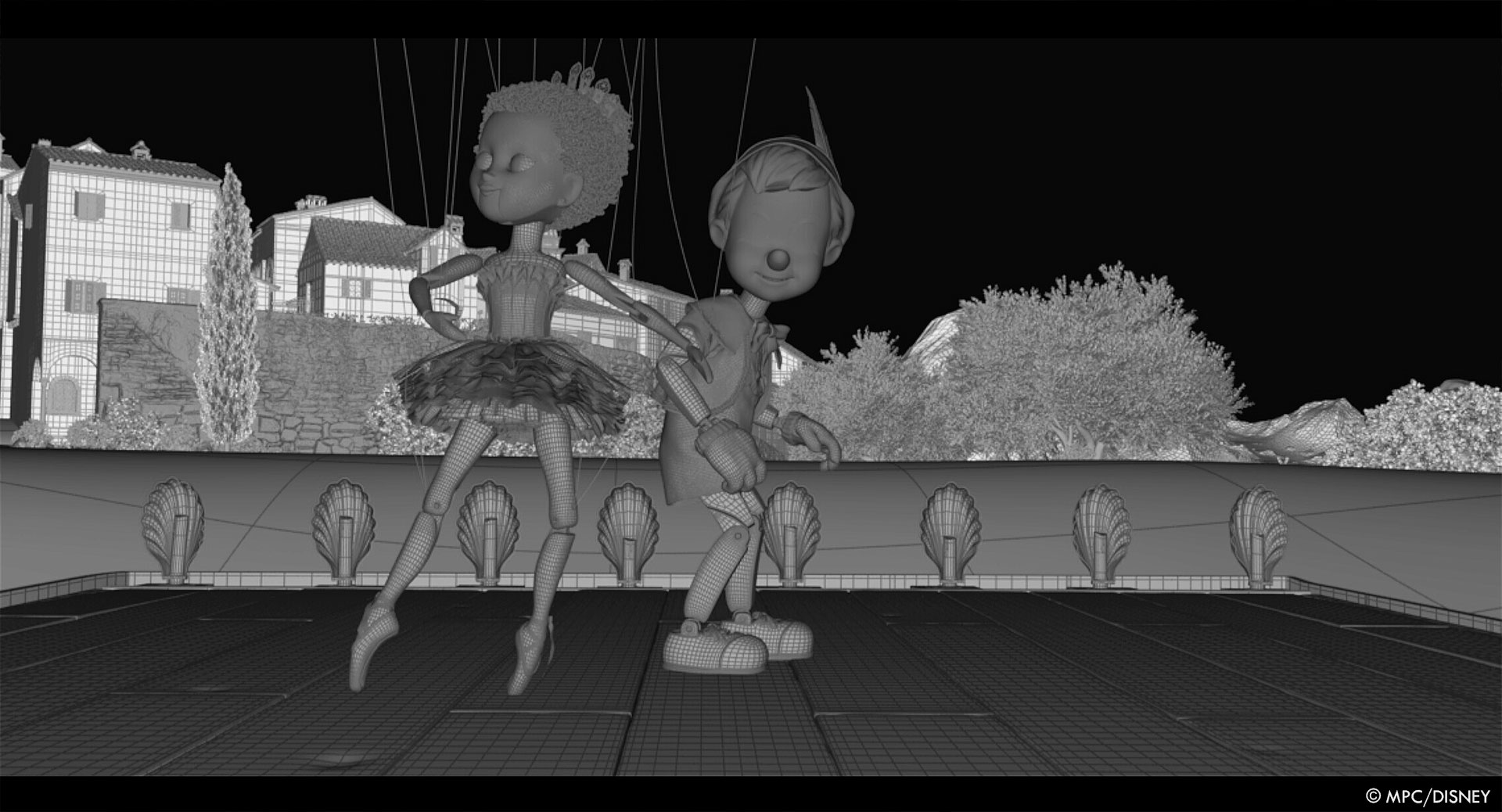

For our puppet characters, Pinocchio and Sabina, we filmed interactive reference-gathering sessions with Master Puppeteer Ronnie Le Drew. He puppeteered real puppet builds, experimenting with different actions to find the character (and limits) of each puppet. That was a really wonderful experience, pulling such a depth of traditional experience into the digital realm!

Can you tell us more about the shaders and textures for the CG characters?

Ben Jones at MPC has an amazing eye for realistic materials on CG assets. He worked really close with Giles and his asset team to make sure they all were totally believable coming out of their Katana/Renderman pipeline.

One thing that really gave us a leg up, as mentioned before, were the physical builds from Joanna and her costume team for assets that would never be seen in live action. The photos and scans that resulted from those efforts were invaluable in creating totally believable clothing on our all-CG characters!

How did you handle the challenges of the size difference between Pinocchio and Jiminy Cricket?

Our Virtual Production workflow was really critical in finding the camera angles that would work for both characters. Because it involved both the character animation team as well as Zemeckis, our DP Don Burgess and our A Camera Operator Pete Wilke shooting virtual cameras, we were able to quickly find pleasing compositions by an iterative process of collaboration.

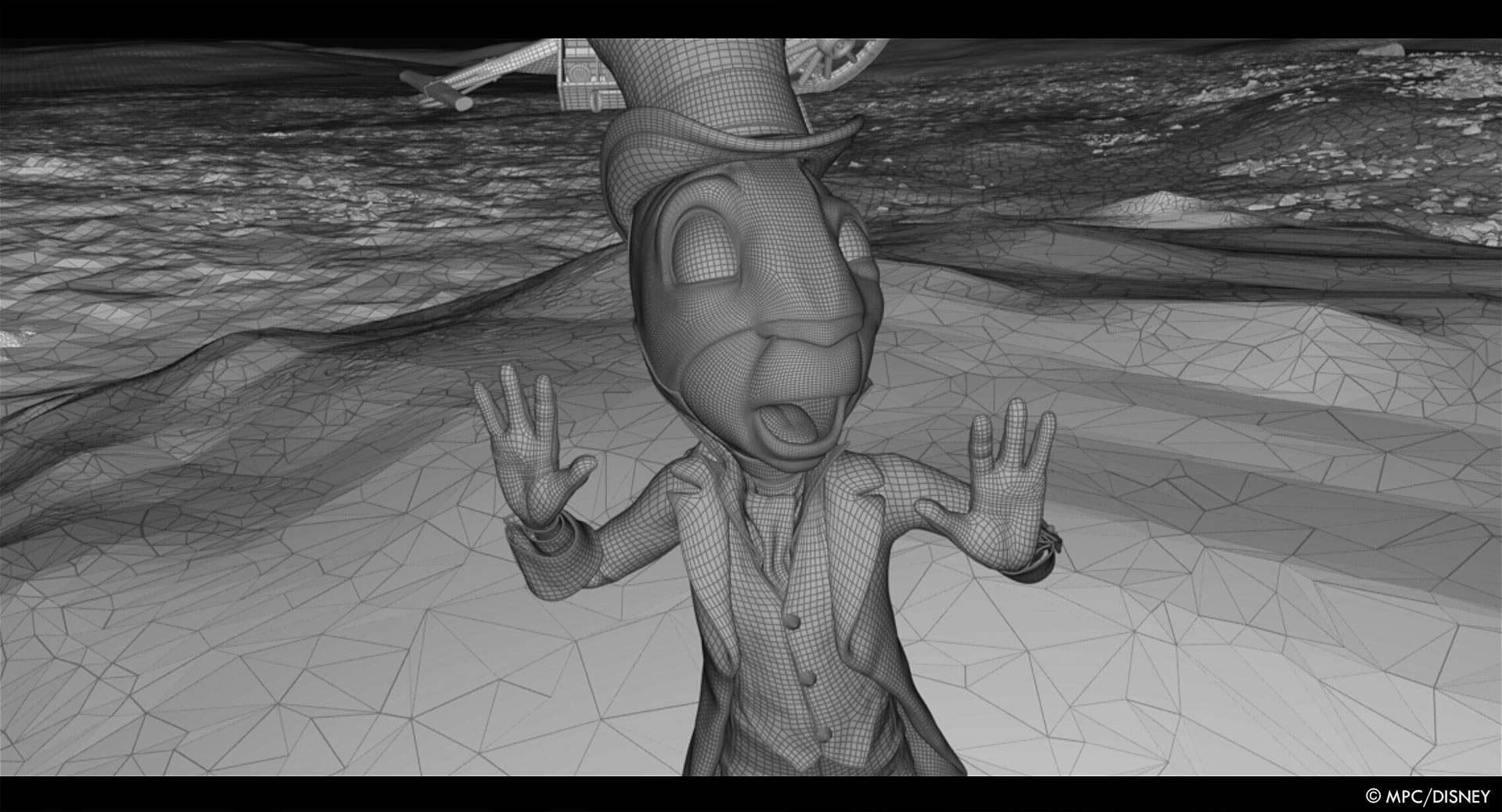

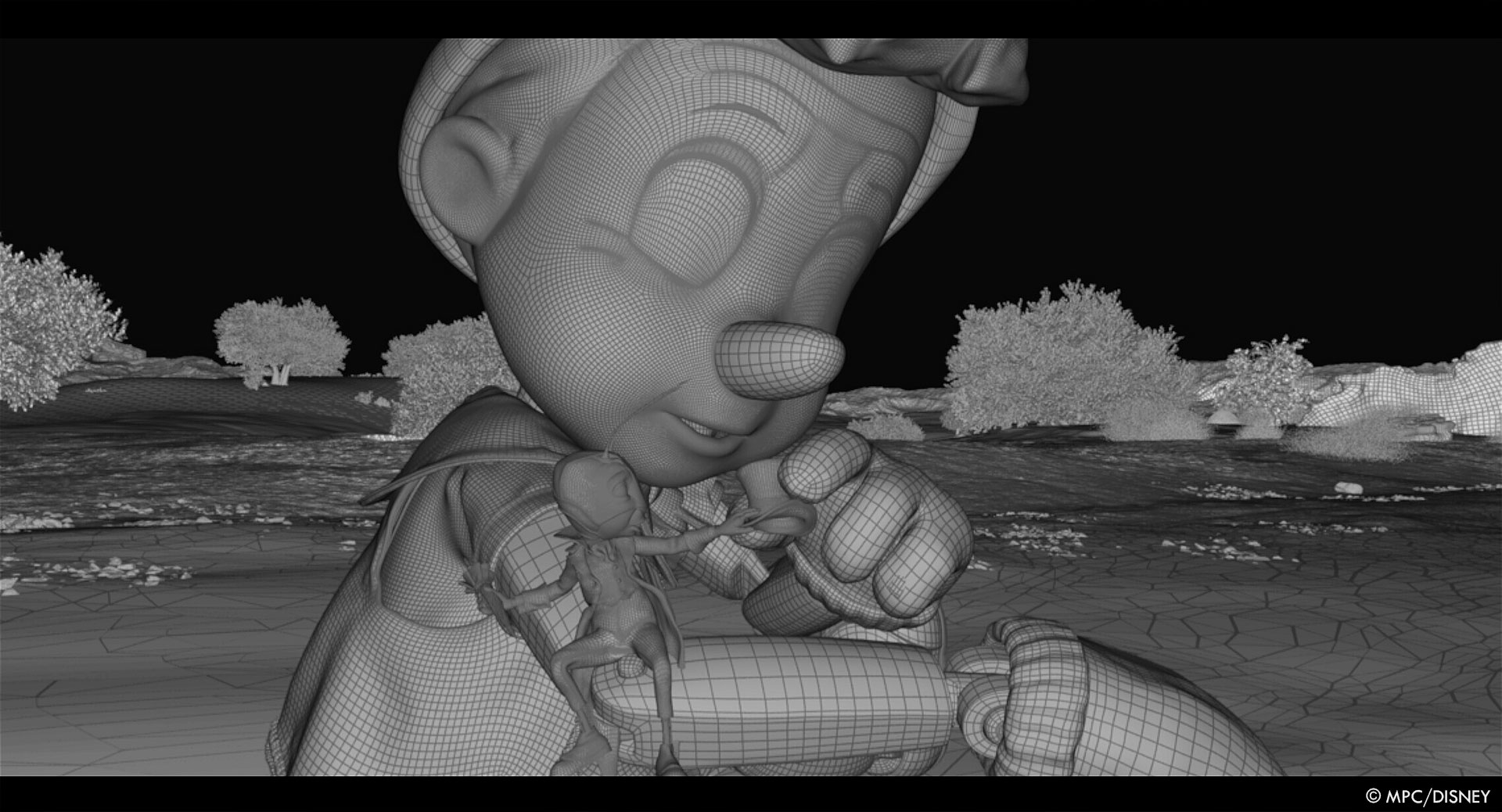

When we get close to Jimmy, Bob wanted to avoid a macro photography look which, given the large-format sensor we were shooting on (Panavision DXL2) would have been the natural result. By using much smaller apertures, sometimes as small as f/64, we could create shots where both characters were readable (not too soft) but still felt cinematic. The way we ended up thinking about this is that, when we were at Jiminy’s level for a shot, we scaled the camera down so that its sensor was in scale to Jiminy. These shots look like you’e watching a human-scale Jimmy filmed with a normal camera – which was Bob’s exact desire.

Can you tell us more about the lighting work?

Virtual Production played into lighting significantly, as it did with every other aspect of the film. Our DP Don Burgess designed the lighting in Unreal with the help of Mold 3D and Halon. This then served as a guide for the live action lighting and, because we were using raytracing and physically-based lighting in Unreal, we could use it as a pretty accurate blueprint for MPC to follow in post-production.

How did you help Tom Hanks and the cast to interact with the CG characters?

Since we had previs cuts for the whole movie, we could make guesses as to how Tom might want to engage with Pinocchio in any given setup. Using this, we worked with props to create a “playbook” for every setup where Tom and Pinocchio would interact. We ended up with a toolkit of different versions of Pinocchio (hero, soft foam, painted foam) as well as different components, like an arm mounted on a metal armature, that could stay low-profile (thus reducing the severity of paint-outs) and still give Tom what he needed to interact with. We also used eye line stands with LEDs where Pinocchio’s eyes would be, of which we could put multiple in a set and remotely turn off the LEDs on one stand and turn them on for another to indicate Pinocchio moving to another location. We also made use of laser pointers and even old-school “ball at the end of a long stick” for eyeliner and to give the camera team something to follow. It was really a “kitchen sink” approach, although a very carefully planned one!

Beside Pinocchio, which character was the most complicated to create and why?

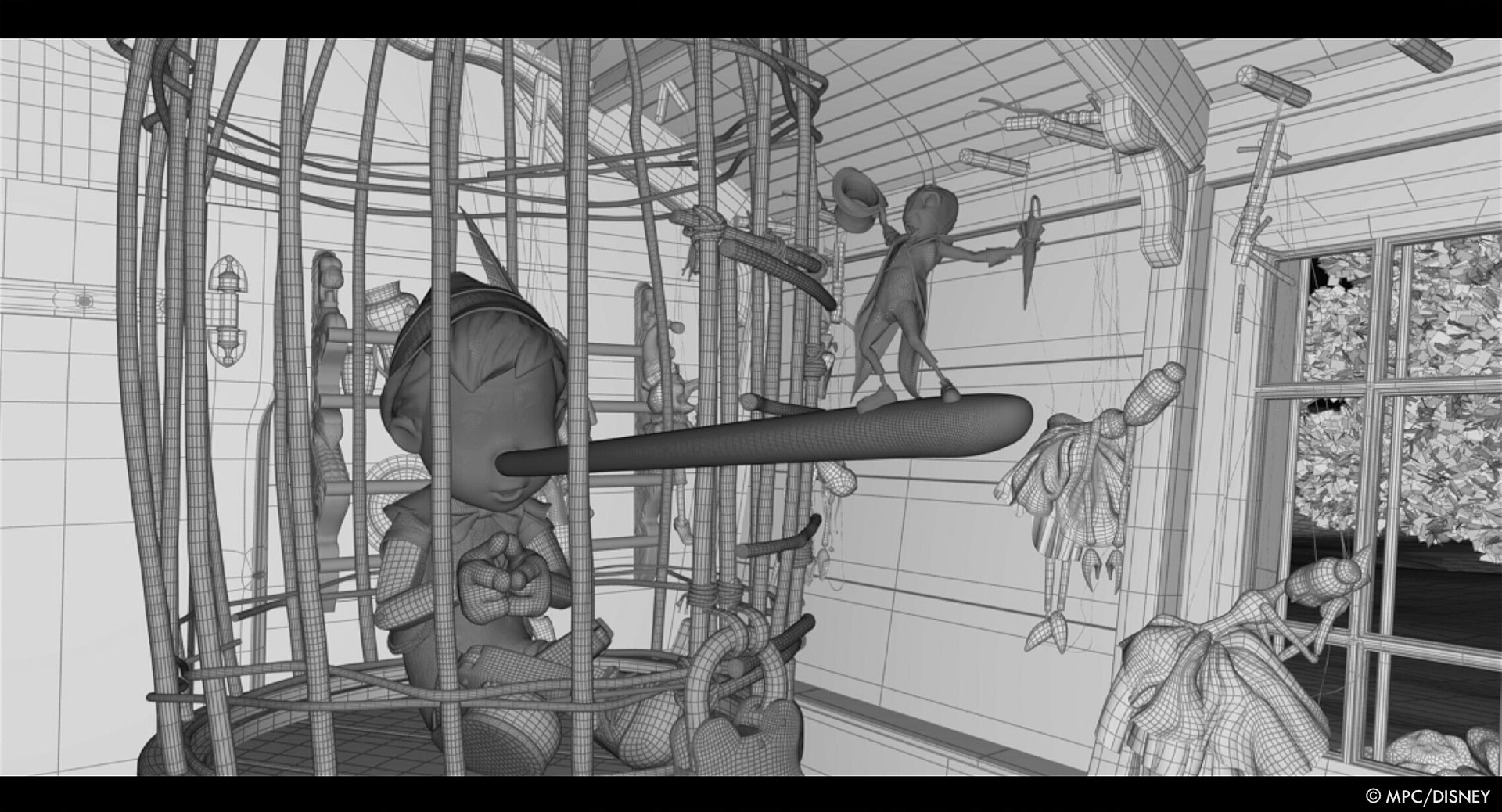

Honest John, the rather cheeky anthropomorphic fox, was probably the most complicated character, since he had multiple layers of clothing on top of fur, and moved in a very expressive manner. This fast, multi-layered motion was a complex task for the MPC CFX team, and they nailed it!

What was your approach to shoot the Blue Fairy?

Filming her was one of the many Virtual Production success stories of the film. Since the Blue Fairy needed to float through the room, we filmed her in a blue void, attached to a c-chaped metal device created by our stunts team and puppeteers by cables and stunt performers in blue suits. Shooting in a blue void is always difficult, since it’s impossible to know exactly what you’re composing for, so we leaned on Virtual Production to help. We’d already built Geppetto’s workshop entirely in Unreal, so we tracked the production camera in real time and live-composited the environment into the blue. BobZ and Don Burgess had one monitor with the raw feed, and another with the real-time comp. The compositions that we worked out on set ended up flowing through perfectly to the final product!

Can you explain in detail about her creation?

Her foundation was based off of beautiful concept artwork from Doug Chiang’s team. Once we had a target nailed down, costumes, hair and makeup and VFX collaborated to bring her final look to the screen. Bob wanted her dress to look like energy was flowing down it, and he was excited by the idea of her wings moving in a non-synchronized pattern – a bit like a cuttlefish’s fins. Her dress itself was practical, as was a the jewelry on her face, and VFX augmented it with the falling energy simulated to follow its features in Houdini, wings animated in Maya, and ribbons of flowing sheer cloth around her arms.

Can you tell us more about the massive size of the whale and how it affects your work?

Monstro was indeed extremely large! This made water simulations very challenging, since we couldn’t literally sim a perfectly realistic result without creating massive waves and spray that covered Monstro himself. The MPC FX team had to get really creative and art direct the simulations to make them feel real, without actually being perfectly true to physics.

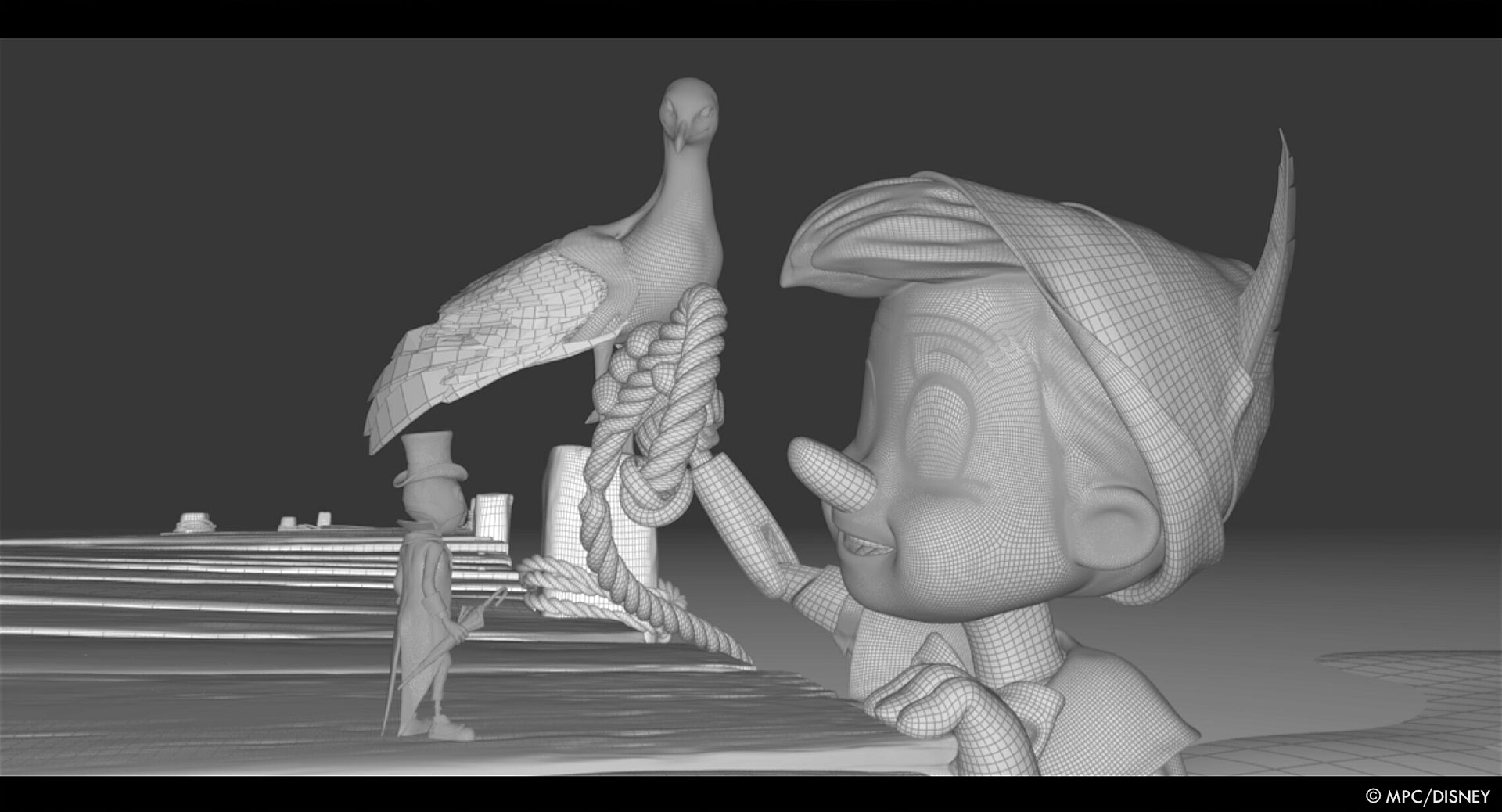

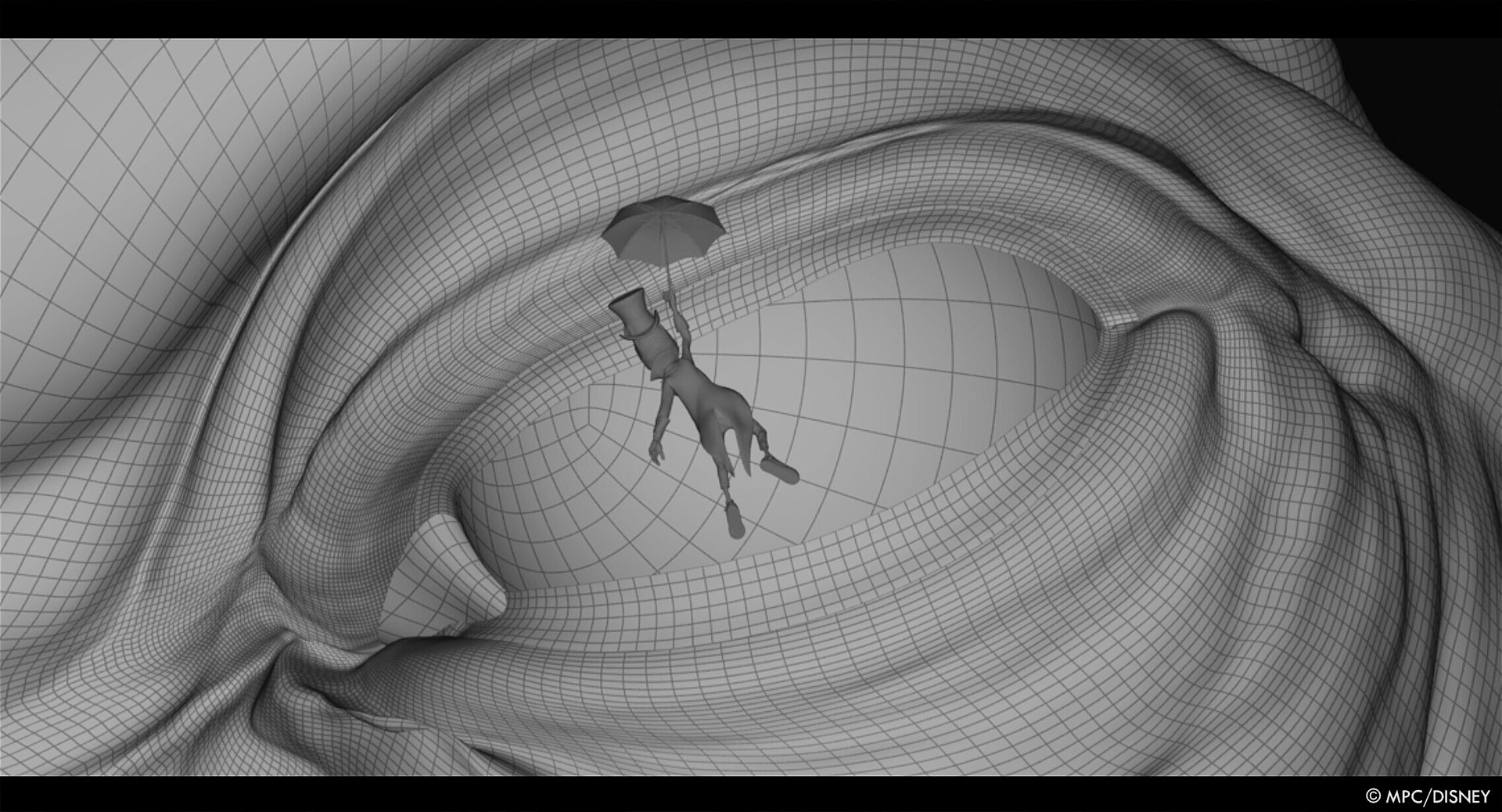

The other difficult thing was achieving pleasing camera compositions of him that also told the story, and often included other characters in the film. Sometimes we had the smallest character in the film (Jiminy Cricket) in the same shot as the largest (Monstro)! Take, for example, the shot where Jiminy floats past Monstro’s eye. Situations like these were where our virtual camera layout workflow was instrumental. We worked closely with Kristin Turnipseed running the VCam stage and Christophe Paradis and his animation team at MPC to guide the action into the zone where it was shootable, and then got the final shots in a virtual camera session. On every show it can be super challenging to manage the relationship between camera and animation, especially for a director like Bob who is always super involved in his cameras, and Virtual Production made it a relative breeze!

Can you elaborates about the environments work?

All of the environments were designed by Dough Chiang and Stefan Decant, who worked closely with their own Virtual Art Department (VAD) artists as well as our VAD team from Mold 3D. We were able to virtually scout these environments many times, and make sure they would work for Bob when seen through the lens of the camera.

Once the environments were approved, some of them would be built for real on our shooting stage at Cardington Studios north of London. Often they would be partial set builds with bluescreen extensions. Since we had the Unreal environments, we’d use various simulcam techniques (helmed by Jim Geduldick at Dimension Studio) to visualize the extensions in real time on set, giving the camera team material to help with their composition decisions.

For Pleasure Island, we build a massive array of LED walls to put our Unreal backgrounds onto. That said, we decided that in-camera LED was not a good fit for the film. Bob wanted as much flexibility in the post as possible, since being able to make decisions in the context of the edit is hugely valuable. By using big, bright out-of-view LED walls, helmed by Callum Macmillan at Dimension, and projecting our previs environments on them, we could get all of the benefits of interactive lighting and reflection without any of the lock-in of in-camera LED walls. It was truly the best of all worlds!

We would scan and extensively photograph all of our physical sets so that we could build all-CG versions of them since we knew that, particularly for shots of Jiminy Cricket, we’d often be cutting back and forth between live action plates and all-CG shots.

For the environments that never had a live-action component, our Production Designers would treat them like they were building live-action sets, and give the teams at Mold3D and MPC as much information as possible to make them look fantastic! MPC did the final builds and ran ‘em through their Katana/PRman pipeline, using physically based lighting throughout. MPC’s environment team really knocked it out of the park with ‘em, I think!

Which location was the most complicate to create?

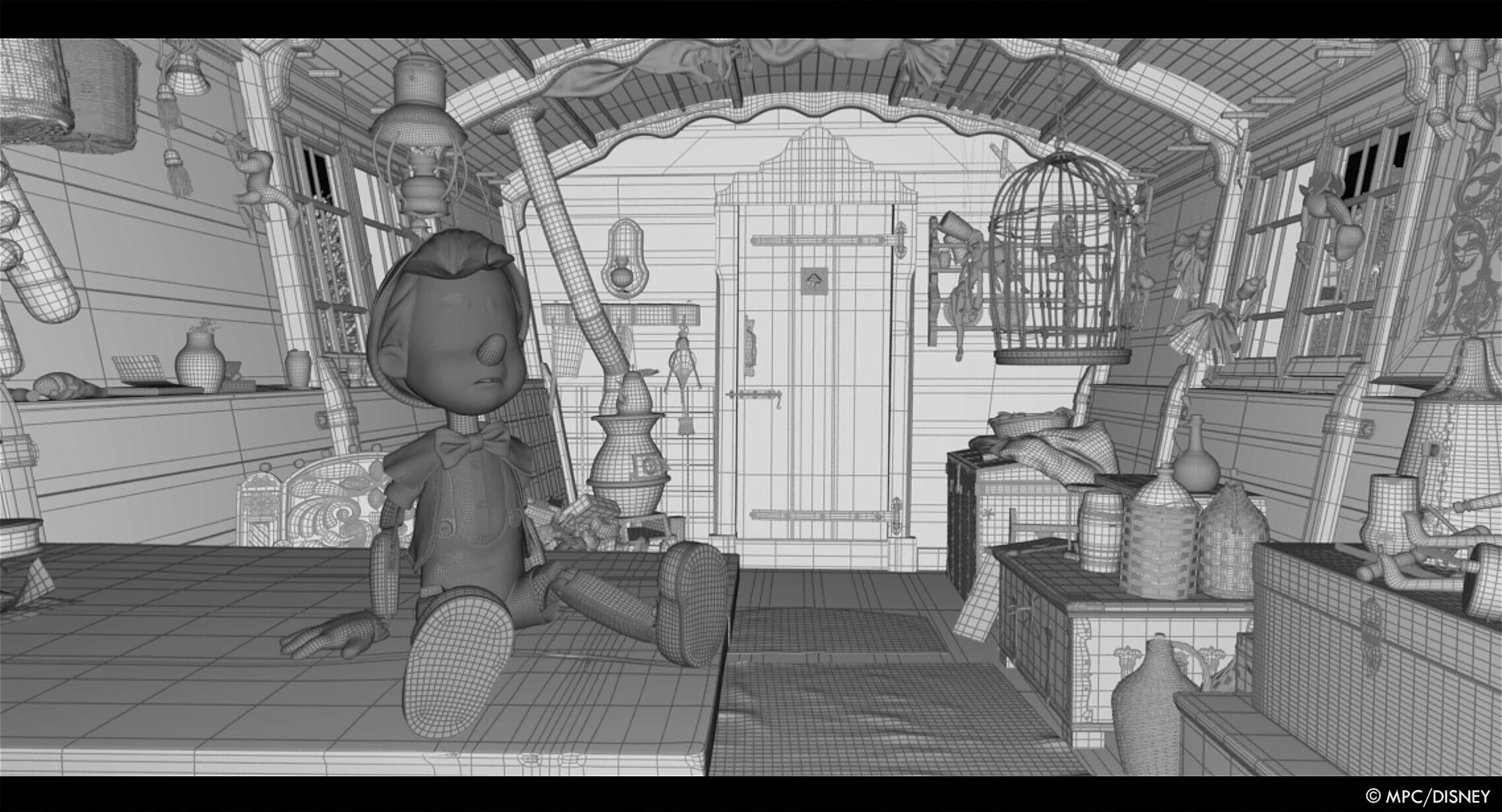

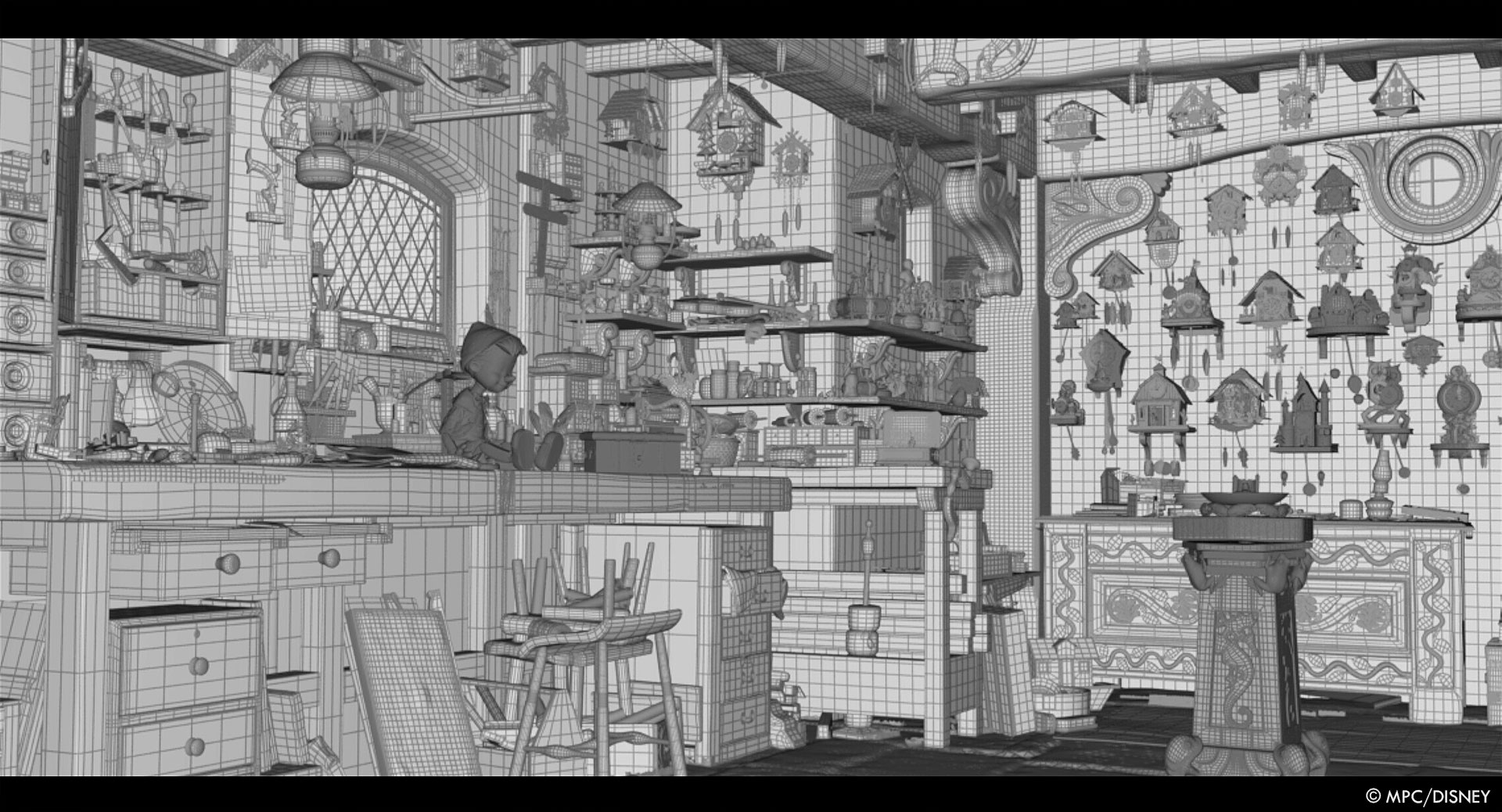

Geppetto’s workshop was by far the most complex environment to build in CG, since the love action set had so many details and tons of intricate set dressing. MPC had to build every item based on set photography and scans, which was a monumental task!

The interior of Mosntro’s belly was also pretty tricky, since water simulate, ship wrecks and bioluminescent plankton were all things that needed to be created and look every bit as cool as the concept art.

Did you want to reveal to us any other invisible effects?

There weren’t a lot of invisible effects in the film, to be honest. I would say the most invisible effects were the ones where we cut back and forth from live action shots to fully-digital ones. This happened a lot in the show, especially in Geppetto’s workshop and Stromboli’s caravan. They’d have to cut seamlessly, which is a tall order!

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

The Monstro chase sequence was probably the most challenging. Not only did it involve lots of difficult and computationally-intensive water simulations, it also was tackled towards the end of the post schedule. We had very few iterations to get the scene across the finish line, which put a lot of pressure on everyone involved.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

Time. There’s never enough time to get everything we want into a film, or make a shot perfect. BobZ has a mantra he frequently uses: “progress, not perfection.” I think it’s the thing that helps me sleep more than zero when time is running out!

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

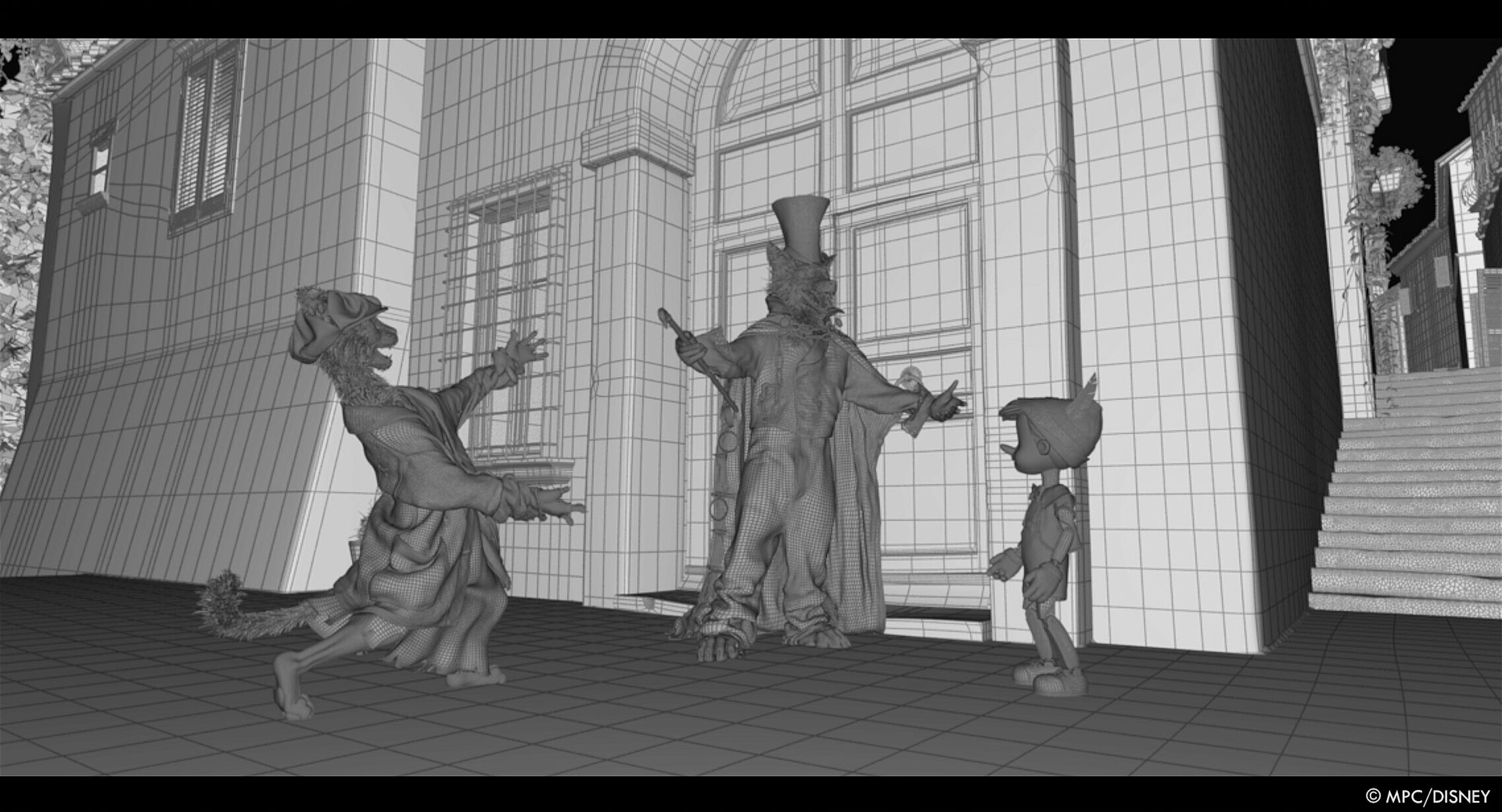

I really love the sequence of Honest John and Gideon trying to convince Pinocchio to become famous. Honest John’s performance is so expressive and fun, thanks to Keegan Michael Kee and the MPC animation team, the environment that MPC built looks fantastic, the lighting design from Don Burgess worked great, the cameras from our A Cam Operator Pete Wilke came through splendidly, and it’s just an enjoyable scene overall. It’s one of those scenes that is both a technical success and super fun overall, which makes me smile!

What is your best memory on this show?

Seeing my name on a movie slate for the first time was really special. Directing the 2nd Unit on Pinocchio was a huge growth opportunity for me, and I was already excited and nervous about that. Walking onto set for the first day of filming and seeing “DIR: Kevin Baillie” as they slated the first setup sent chills down my spine. It’s honestly something I never expected to be able to do, so it caught me off guard a bit – made it feel like it was actually real for the first time! And, honestly, I had so much fun doing it! My 2nd Unit DP Matt Windon and AD Sam Smith were such great supporters and collaborators, which made it all the more fun.

How long have you worked on this show?

I started pre-production in July of 2020, so it was over 2 years from beginning to end!

What’s the VFX shots count?

There were 965 VFX shots in the film, plus 10 shots that weren’t VFX, for a total of 975 shots in the movie. Bob like his long shots, so we rarely exceed 1000 total cuts on any of his movies!

What is your next project?

I’m working with Zemeckis again, of course! 🙂 We’re working on a film called Here, which is based on a graphic novel, and stars Tom Hanks, Robin Wright, Paul Bettany and Kelly Reilly.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

MPC: Dedicated page about Pinocchio on MPC website.

Disney+: You can watch Pinocchio on Disney+.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2022

How long have you worked on this show?

I started pre-production in July of 2022, so it was over 2 years from beginning to end!

there is a typo in the above statement. I think it is « July of 2020 »

Thanks!