In 2015, Kevin Baillie explained to us the work of Atomic Fiction (now Method Studios) on THE WALK. He then worked on STAR TREK BEYOND, ALLIED and the TV series, MANIFEST. Today he talks about his new collaboration with director Robert Zemeckis for WELCOME TO MARWEN.

NOTE: In July 2018, Deluxe Entertainment acquired Atomic Fiction, which is now Method Studios. The VFX work on Welcome to Marwen is credited to Atomic Fiction.

How did you get involved on this show?

I have a long-standing relationship with the director, Bob Zemeckis, and he involved me early in the process – before the project was even greenlit. I was BBQ’ing in my back yard in 2013 when Bob called me about a script he’d written based on the documentary MARWENCOL. He sent it to me and I was blown away by the interplay between the fantasy world, which take place purely in Mark’s imagination, and his somewhat sad reality in which he’s overcoming the PTSD from a hate crime he’d suffered. As we started talking about how to execute the film, I pulled together a team of concept artists to determine how to realize the doll characters and the village itself. Emmanuel Shu and Marc Gabbana did the initial village layout and developed the look of interiors/exteriors, including the how the Ruined Stocking Bar would integrate into both the inside and outside of Mark Hogancamp’s trailer, and Vladimir Todorov designed the initial look of the dolls. Then we figured out the how translate the actors’ performances to the doll characters and created test footage to present to Universal. We used that whole body of early work to get the film greenlit. The project was really interesting because VFX was spearheading initial concepts and everyone leapt off of that. Production Designer Stefan Dechant, for example, took our good set design ideas and made them better, and replaced our not-so-good ideas with great ones. Every department worked together with the shared goal of making the best-looking film possible!

How was this new collaboration with director Robert Zemeckis?

Every collaboration with Bob Zemeckis is fantastic. He is a consummate team player, and once he finds a team that he’s comfortable with, he trusts them implicitly. He leans on VFX to bring in our expertise and listens to our input, and he does that across every department. He’s a great listener and aggregates all that feedback in making his decisions, creating better results as a team than any one person could ever achieve on their own.

How did you use your experience on his previous movie for this new one?

I’ve worked with Bob for more than a decade, since A CHRISTMAS CAROL, so I’m pretty familiar with the way he goes about designing environments and characters. There are certain stylizations he prefers so we steered our character design with that in mind. I had the great pleasure of working with makeup designer Bill Corso to help guide the doll design process, and leverage Bill’s incredible ability to create doll faces that had a beautiful aesthetic, were very doll like, and would still resonate with Bob’s particular design sensibilities. Also, as I mentioned previously, Bob trusts his collaborators. When we ran into an issue during post production, we’d talk it through and I could say ‘I’ll show you the fixed version in a week’ and he wouldn’t worry about it. When a director is familiar with and trusts the VFX Supervisor, it streamlines the creative process. Bob knew that once he shared his feedback, we’d nail it and there didn’t need to be five review sessions in the meantime. That ultimately served as a tremendous asset in streamlining the process of getting this very challenging film out the door!

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

Our VFX producer, Sandra Scott, and I have worked together for ten years, much of which has been on Bob’s movies. The same way Bob’s trusts me with certain creative and technical aspects of production, I trust Sandra with production-side logistics. We have a great partnership; she’ll ask for my opinion on budgets and scheduling and I’ll ask for her input on creative or logistical problems, and I rely on her to tell me when we’re getting close to hitting limits. We’re a true team and our roles are integral.

How was the work split amongst vendors?

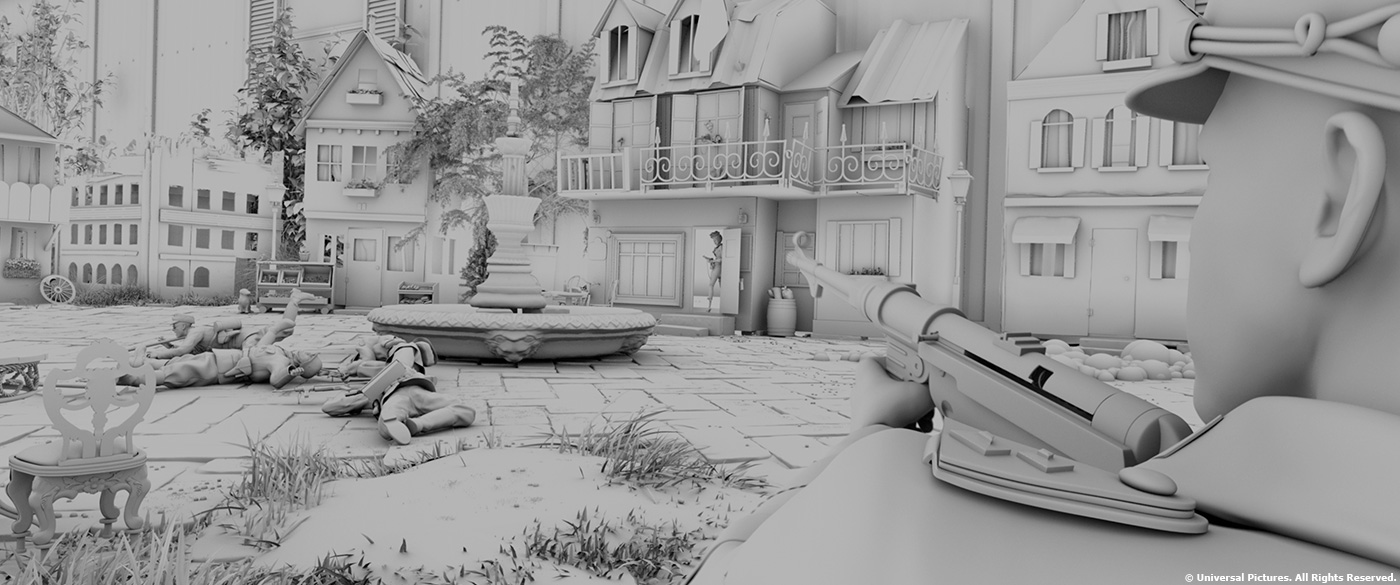

Atomic Fiction (now Method Studios) handled 509 of the film’s 655 VFX shots. We created the digital Marwen world and the CG doll versions of 17 characters. Framestore handled 82 VFX shots, focused on the opening sequences of Hogie crash-landing a P-40, and Method Studios handled 64 VFX shots, focused on performance blending, the “drunk effect” in Mark’s flashbacks, and turning sequences shot in Vancouver into New York City. Creation Consultants, led by Dave Asling, fabricated all miniatures, including 24 hero dolls comprising 17 characters, plus backup duplicates of the leads and a set of stunt dolls, the town of Marwen – 14 buildings around a courtyard with a fountain –the P-40 aircraft and a DeLorean built out of Legos. Profile Studios handled the mocap stage setup and virtual production workflow, and Day For Nite assisted with previs and postvis.

Can you tell us more about the previz and postviz work?

There were two categories of previs, with the first being to help figure out scene action like plane crash in beginning of film and DeLorean flight at end, as well as shot where Jeep comes barreling out the door of hobby shop and transitions to live action. Those were used to drive a hydraulic motion base on set that moved the actors so they physically responded as if they were in a vehicle. The other use for previs on-set was to pre-determine lighting. To bring the actor’s souls to their dolls, we determined that traditional mocap wouldn’t do the trick. Instead, we’d be projecting actual footage from the actors’ faces onto underlying digital renders of the dolls’ faces. This meant we had to light the mocap stage as if it were the final movie, and the final digital lighting would have to match exactly to what we did on the mocap stage. Talk about a moonshot! We built a real-time version of every mocapped scene and optimized it for Unreal Engine. We armed our DP C. Kim Miles with an iPad that had custom controls that allowed him to adjust sun position, sky brightness and several custom lights. He talked to Bob about the actors’ blocking and what the shooting orbits would be, then spent two weeks pre-lighting every scene so that by the time we got to the mocap stage, the crew already knew the lighting setups. During shooting, we had one monitor with the Alexa 65 feed and one with a real-time view of what the final composite would look like. In essence, it was “lighting previs” that flowed into the virtual production process. For shots that didn’t feature an actor’s face, Bob would pull up the mocap takes and frame them after the fact. Profile Studios set up a virtual camera system in his office and that allowed him to lay out camera moves for a couple hundred shots after the main unit shoot had wrapped.

How did you work with the miniature effects department for the design of the dolls?

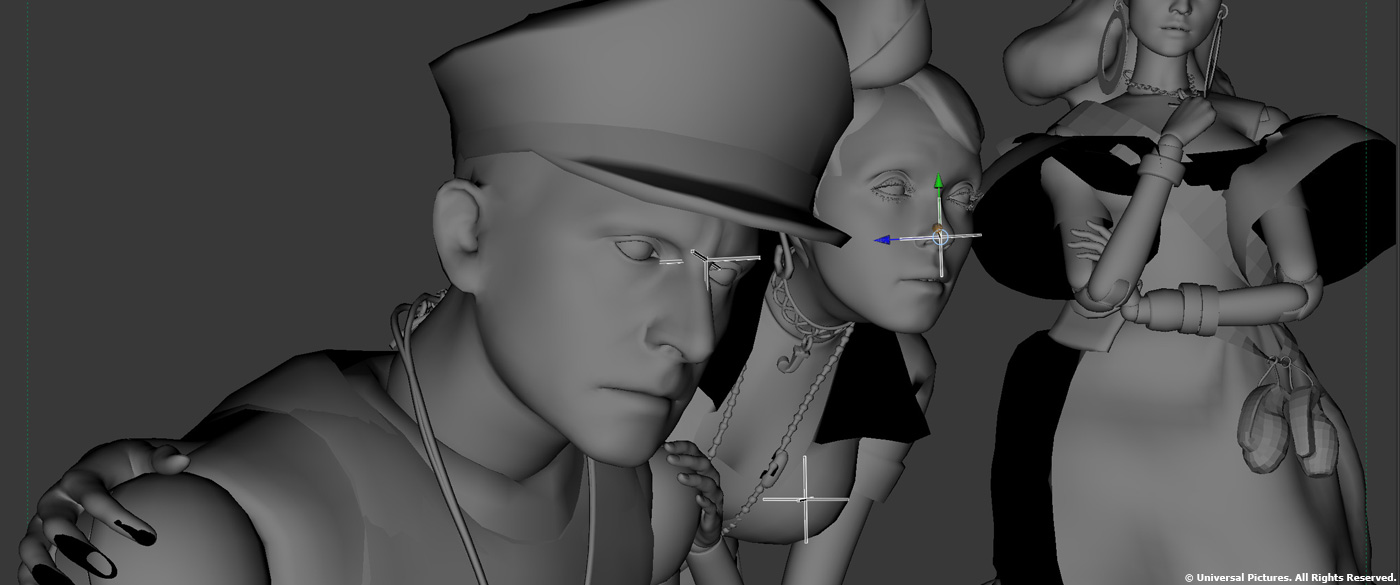

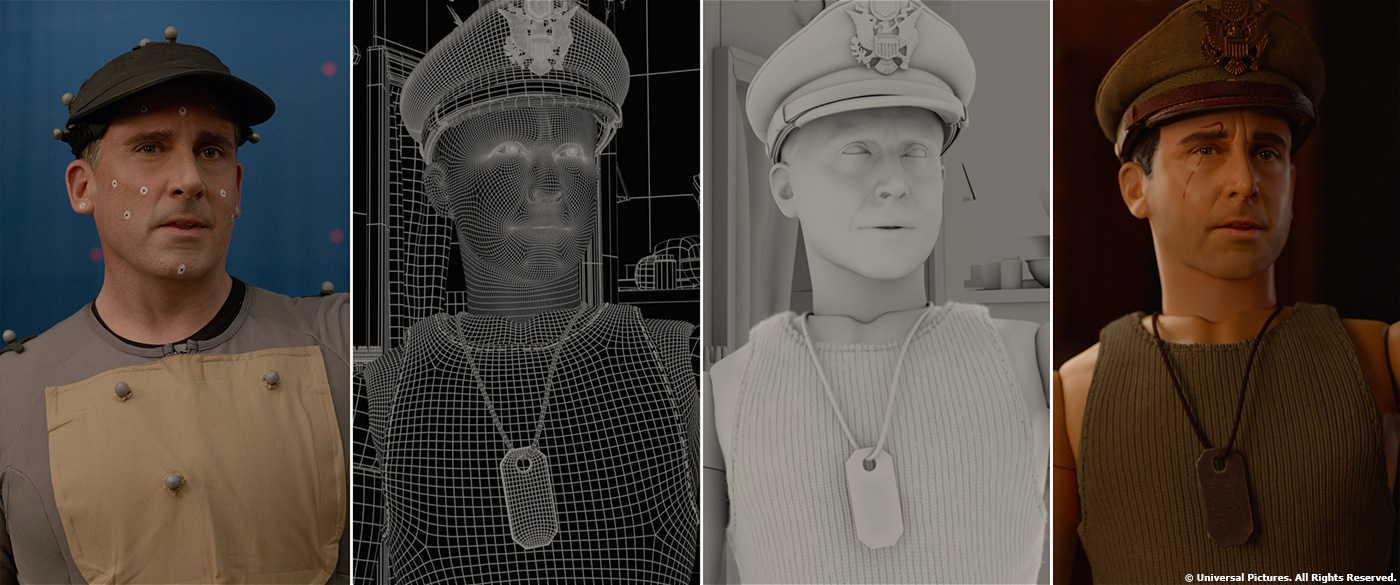

Each doll started as a 3D scan of the actor. That scan was then digitally sculpted into their heroic doll alter ego (as designed by Bill Corso) by Atomic Fiction. Miniature Effects Supervisor Dave Asling and the miniature effects artists at Creation Consultants translated those sculpts into articulated dolls that were 3D printed and pressure-cast, then hand painted to match the approved designs. The dolls’ costumes were designed and created by Joanna Johnston, who provided the patterns to our VFX artists so that we could create an exact digital replica. Atomic Fiction used the physical dolls to create the final digital assets and incorporated them into our pipeline, creating fully rigged CG versions that matched their physical counterparts down the hair follicles, scratches on the plastic and fuzz and threads on their costumes.

Can you explain in detail about their creation and especially their faces?

If you look at an off the shelf doll, they do not have neutral faces but instead generally come with a default expression that embodies their character’s attitude. Bob worked with each actor to come up with their default pose, and the they would act that pose as part of the 3D scanning process. Hair was especially interesting for the women. Dave’s miniature-making team ended up chopping off the backs of their heads and re-sculpting a foundation layer so that doll artists could insert individual hairs, often only 3-4 at a time, and style the hair to match the designs of Bill Corso and the hair stylist, Anne Morgan. One hair style took a full week to complete all on its own!

Can you tell us more about their rigging?

Real world dolls are rigid plastic so we wanted to convey that same feel. We also needed the dolls to hit certain poses and replicate what the actors did on-set, so we found ways of adding subtle stretch and deformation to certain areas like the clavicle. The double-jointed elbows and knees brought another interesting component to the rigging process. To get strong silhouettes, the animation team had to decide action-by-action how much bend to add in which section of each joint to make sure it looked good. While the actors’ movements served as the base for the animation, significant retargeting was required; the dolls are all the same height whereas the actors’ heights vary, in some cases by as much as a foot, so we added subtle squash and stretch in length to retarget the motion to the appropriate proportions. The doll faces were all created using a traditional FACS-based rig and hand keyframed to match Alexa 65 footage that would later be projected on top of them.

How was the performance capture filmed?

The performance capture stage was set up just outside of Vancouver by Profile Studios. While the mocap process itself was fairly straightforward, the challenge was lighting and filming Alexa 65 footage on the mocap stage. That meant we had to make sure the lighting didn’t interfere with the infrared tracking cameras and that we accurately captured the position of the camera on the mocap stage, even when it was mounted to a Technocrane or Steadicam. Sometimes it was a challenge to find places to put the markers so that we could avoid occlusions, but Profile and the special effects team were a great help in building the necessary mounting points.

What was your approach to the animation?

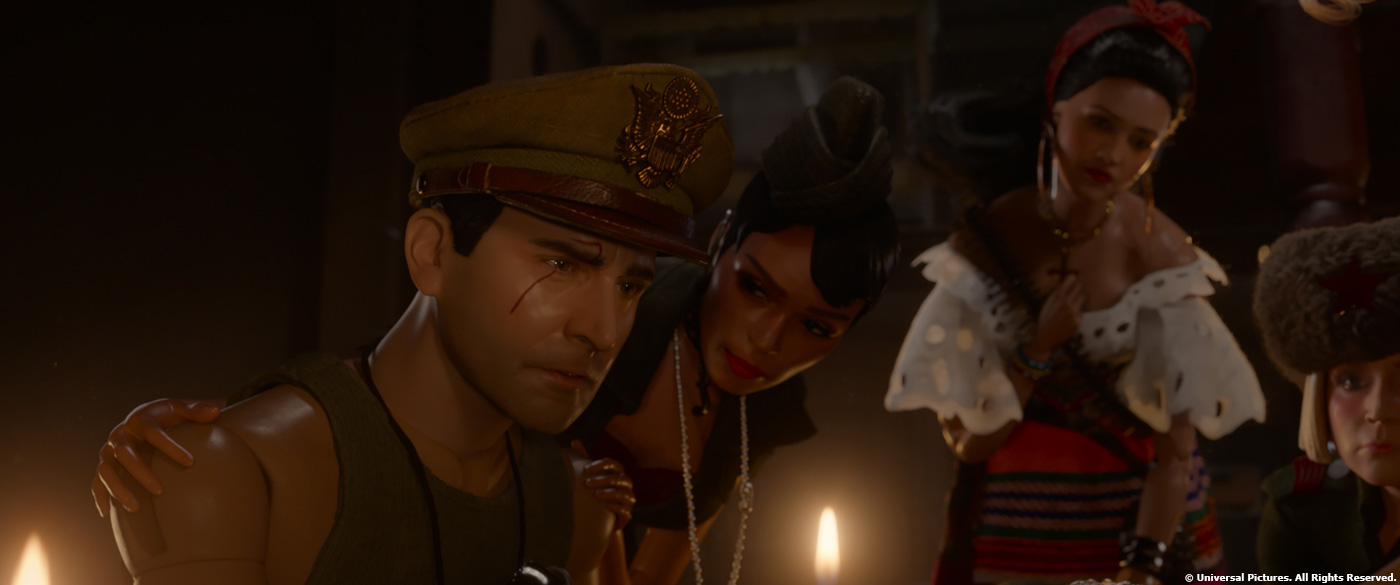

Artists at Atomic Fiction and Framestore used cleaned mocap data from Profile as the starting point, then applied the animation onto the final dolls with the goal of matching what the actor did as closely as possible within the constraints of doll movement. We added things like sticky joints and other subtle movements to underscore the fact that these characters are dolls, not people. We also took occasional liberties with the inanimate nature of the dolls. For example, at the precise moment the Nazis die during a gunfight, we turned off the mocap data and initiated a rigid body dynamics simulation so the dolls clatter to floor like a real doll would. The doll faces were 100 percent hand keyframed to match the Alexa 65 footage. While we used projections of the actors’ real faces for the doll faces, specular and reflection components of the underlying CG renders were subtly layered on top of those the projections to plasticize the result, seamlessly fusing the live action and CG doll footage. We couldn’t have done the doll faces with just animation, or with just projections – both had to work in tandem to get the perfect, “soulful” result!

Did you receive specific indications and references from Robert Zemeckis about the animation?

Bob values his actors and the performances they deliver. Anytime we needed reference, we referred back to the actors and cuts editorial was giving us.

How did you create the various materials, shaders and textures?

Atomic Fiction used RenderMan and Katana to render their portion of the film. Most of the materials we made are based on RenderMan’s PBR shaders in versions 21 and 22. The textures were made in MARI and Photoshop, and we also used Substance Designer to help with the process. The look of various materials was important to selling the appropriate scale. With every piece of clothing, you can see individual threading and fuzz break the profile of the garment, so we did custom fur grooms on almost every single piece of cloth to sell its miniature scale. In fact, there are hundreds of things in world of Marwen that needed fuzz because of the small scale, but wouldn’t have if scale was normal.

How does the size of the miniatures affect your lighting and animation work?

We built the dolls and environment at real-world (one-sixth) scale. The biggest challenge from a rendering perspective at that scale was focus; at one-sixth scale with a massive Alexa 65 sensor, things get soft really quick. We developed special workflows to allow us to keep hero actors in focus while also selling a macro, photographic look. We used digital versions of traditional optical tools like tilt shift lenses and split diopters to do that. My favorite piece of tech that we developed for the film, because it’s “new school” born out of “old school,” is something we called a variable diopter. It allowed us to sculpt and animate a curtain to set focus distance across the frame. This allowed us to keep five dolls sitting in a u-shape around the bar, for example, all perfectly in focus while the image still fell off into softness around them. From animation perspective, we had to experiment a lot with cloth simulation scale. If we simulated as rigid as one-sixth scale, it was too stiff and didn’t look like real clothing; it barely even moved. At full-human scale, the cloth looked too recognizable and the dolls started to look like people in suits rather than like dolls. We had to find a default simulation scale that looked relatable and also doll-like; that ended up being about one-third scale.

Can you tell us more about the lighting challenge?

Our DP C. Kim Miles gave us a great head start in figuring out lighting through the virtual production process. Because we were dealing with extremely shallow depth of field in most cases, we rendered shots in single pass where possible. That meant we had to focus on lighting the world like we would light a practical set and we couldn’t break things into passes and cheat. The other thing that we realized in post production is that when the light direction from the set didn’t match exactly, the characters would look really weird because we were using actual footage from the actors’ eyes and mouths on the doll faces. If the underlying renders had lighting that was even slightly off from what the footage had, then the whole illusion would break. I was very thankful for the virtual production process that we established early on because we found that, while we could change the color and intensity of the lighting to a certain degree, there was no leeway to alter the light directionality.

How did you manage the various transitions between the animated characters and their toy versions?

Every transition required a different technique. Sometimes we would paint out plate dolls and replace them with CG ones that we’d simply freeze to signify the transition. Other times we would do comp morphs between real and CG dolls, or hide transitions in a wipe of some sort. There wasn’t really a formula; each transition was a one-off.

Can you tell us how you choose the various VFX vendors?

We wanted most of the work to be done at Atomic Fiction because Bob is familiar with the team and we all work well together. We also enlisted Framestore and Method Studios to help with some pieces because we knew they were more capable; Framestore did the film’s opening scenes up until the women rescue Hogie the first time, and Method did a lot of performance blends and turned Vancouver into New York for shots. All the vendors ended up being amazing, and I’m very thankful for their tireless efforts on the film!

Can you tell us more about your collaboration with their VFX supervisors?

Framestore Montreal is fairly close to Atomic Fiction, so I could easily meet with their VFX supervisor, Romain Arnoux, whenever I felt like it was going to help the process. As we were narrowing down our methodology, we invited Romain and his team to Atomic Fiction and walked them through our approach. My personal opinion is that consistency of VFX is very important in filmmaking, more so than protecting some proprietary process, so we were very transparent. Christian Kaestner also jumped in at the end of the show; he’s an old friend and I loved working with him. Method VFX Supervisor Sean Konrad is incredibly smart and talented. He would always address every note and would provide additional suggestions to make shots even better; we often ended up going with his suggestions. Working with Sean, VFX Producer Sheena Johnson and the rest of the Method Vancouver team was a big part of what made me really excited to join Method through the acquisition of Atomic Fiction.

How did you proceed to follow the vendors work?

We conducted some meetings in person but did the majority of reviews over cineSync with Shotgun serving as the central hub for tracking notes. Bob and his incredible editorial team are located just outside of Santa Barbara, California, so we did most of our reviews with him remotely as well. These logistics, which got pretty dang complicated from time to time, were masterfully orchestrated by our VFX Production Manager, Francesca Mancini, with support from a small but very talented production-side team.

Which sequence or shot was the most complicated to create and why?

The final battle that happens outside at night in Marwen had almost every character – as well as a DeLorean convincingly built out of Legos. That’s one of the assets I’m most proud of, in fact, since it is so subtly detailed – down to the glue coming out of the seams between Lego bricks and individually-modeled filaments in every bulb of the Christmas lights that wrap around it. That scene has a lot of hand keyframed animation in addition to mocap, and required significant previs. At the end of the scene, we also had to recreate the time travel effect from “Back to the Future,” which Bob walked us through how he did in the original film. It was a pretty giddy and surreal moment for all of us artists as he explained it.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

46 minutes of the movie takes place in the doll world so the sheer volume of work was intimidating. Not only did we have to execute, but we had to figure out how to do it in the first place. We were finishing well over 100 shots per week in the final weeks to make sure everything looked consistent and amazing. From the very beginning of the project, our mandate was to bring the souls of the actors to the dolls in a way that avoided the uncanny valley. Since the uncanny valley is a purely emotional response, driven by ancient survival instincts, there wasn’t some formula that we could be sure would work, or a measurable objective threshold that we knew we had to aim for. Projecting the actors’ faces on to CG dolls seemed like it would work, and the tests we’d done in pre-production looked promising, but we didn’t know for sure how it was going to turn out until well after the movie was shot. When we saw the first shots come together, and could feel the emotions of the actors come through endearingly in the results, then I could finally sleep again!

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Towards the beginning of the movie, there’s a scene in which the women dolls are all gathered around the bar. They have a relatively normal conversation, and Hogie toasts to them with his coffee mug. It’s a subtle, dialogue-driven scene that’s beautifully lit. You can see all these dust particles floating in the air and there’s a shallow depth of field. The characters are just having a conversation and, when I watch the scene, I find myself forgetting that they are dolls. I think that’s the ultimate sign that we succeeded in the goal we’d set out for – when the audience can see characters interacting with one another, rather than a visual effect.

What is your best memory on this show?

My youngest child was born in prep! And when I finally got to see the scenes put together during the color grading session at the end of the film. We spend so much time obsessing about individual shots, pointing out every flaw in them as we go along, that to see the entire body of work assembled, and looking beautiful, was an incredible feeling.

How long have you worked on this show?

5 years.

What’s the VFX shot count?

655.

What was the size of your on-set team?

We generally had about five VFX-specific people on-set at a time then, once we spun up the mocap stage, there were about 15 people helping manage the mocap process from Profile Studios. I’d like to give a special shout out to Ryan Cook for handling VFX Supe duties for me while I was at home with my newborn.

What is your next project?

I can’t talk about it yet but, of course, it’s really cool!

A big thanks for your time.

WELCOME TO MARWEN – VFX BREAKDOWN – METHOD STUDIOS

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Method Studios: Dedicated page about WELCOME TO MARWEN on Method Studios website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2019