In 2021, Simon Stanley-Clamp discussed the visual effects work on Fate: The Winx Saga. Since then, he has contributed to Matilda: The Musical, Lift, and True Detective: Night Country.

At what stage did you become involved and what was the director’s approach to the visual effects?

Cinesite was involved from pretty early on. After reading the script we had a session with director Alex Garland and the producers on the show, who at that point hadn’t assigned a vendor or VFX supervisor.

I had already read the script and we did a pitch presentation in that session. I had compiled a sizzle reel of relevant and related content; I was trying to get a flavour of what Alex liked and what he didn’t. Alex gave a run through of what the show is about and the factual approach, with physically plausible camera work, as if in a documentary. Cameras would be handheld or on legs moving around with the soldiers, and there would be no showy VFX or aerial shots; everything would be very much grounded in reality.

Cinesite was the sole VFX vendor for Warfare, except for the in-house team; a group of four artists from Cheap Shot who worked alongside us and VFX editorial for the production.

Who did you report into and can you describe your working relationship with the client?

Kaley Edwards was the visual effects producer on the production side. Allon Reich was the producer we worked mostly with (from production company DNA Films), and there were also the directors Alex Garland and Ray Mendoza. It was a great production in terms of communication; all of the HODs interacted with each other. There were weekly production meetings and once the production offices were set up at Bovingdon Airfield, where Warfare was filmed, most people were based there during construction and for setting up the show. So all of the departments interacted very closely together.

Can you give an overview of the premise for the film?

Ray Mendoza had been a military supervisor for Alex Garland’s film Civil War. An ex-Navy SEAL, he had fought in the Iraq War in 2006 and he told Alex about his experiences in a platoon on a mission into insurgent territory. Together they wrote the script for Warfare about an event which took place over 36 hours – SEALs are deployed to investigate and observe insurgents, but it goes wrong and the action follows the attempts to rescue the first unit and to escape. So it’s based around a real event and how the soldiers on the ground experienced it.

An example of how that approach informed VFX decisions was in the use of night vision goggles. The film opens with a nighttime assault, which we had planned to show through night vision goggles; we had tested with and captured reference in order to replicate that look, filming normally and then adding the look in post. However, when we were in post and editing, Ray asked the question, “Who is wearing the goggles?” The audience is supposed to experience the action like an observer, not a soldier. So at the end of the day, we lost all of those night vision shots and the scene plays out very darkly, as if it was seen at night and as our own eyes would experience it.

Where and how was it filmed?

Warfare was filmed at Bovingdon, a former Airfield which is now a film studio, in Hertfordshire. Soon after I came on board the production the area was still ostensibly a carpark, taped out with some painted lines and rudimentary scaffolding. We would be building out that big carpark space with a street, where the action takes place, backed with blue screens where we would be extending the set out digitally to add farther areas of Afghanistan. The build progressed very quickly once we were in pre-production.

The plan was to build as much of the street as we could, to give the camera freedom to roam up and down as far as possible. A full street of around 15-20 houses was constructed, surrounded by blue screens, some of which were floating that could be positioned anywhere we were seeing the top of the set against the sky or trees. The film was entirely shot on that set at Bovingdon.

It’s a film with lots of gunfire and explosions. How were the pyrotechnics handled and where was the crossover between physical and digital effects?

We worked very closely with the SFX team, who did a fantastic job. As far as possible, everything would be captured practically, but the role of sound was also very important to the shoot and capture process. The whole set had speakers embedded into it, throughout. So when you hear a gun go off, you would hear it on set too. When a jet flies over, that was amplified. When a dog would be barking on the street, you would hear that too. All of that gave a great sense of realism during on set capture, for both actors and crew. The guns were firing blanks, but they were incredibly loud; we all wore ear defenders throughout the shoot. There was a visceral effect to the noise and a byproduct of that is that the guns, even though they’re firing blanks, give off a shock wave which on occasion interfered with some of our lighter-weight cameras, for example the DJI Ronins. We actually mimicked that effect for some of the shots with the biggest bangs. There were also masonry squibs so that when the bullets appear to hit the walls, dust is kicked up, giving the soldiers something to react to. Sometimes, the timing wouldn’t work so we needed to reposition them or replace them with our own CG squibs to ensure continuity.

However, the tanks never fired, so that is entirely CG, from the muzzle flashes through to the puffs of dust ejected as each shell is fired. Where their projectiles hit walls, they are either entirely CG impacts or augmented SFX. I spent a whole day shooting blue screen explosions, muzzle flashes, smoke, masonry hits, sparks, a whole gambit of SFX which we could use, matching the same guns and artillery which would be used during the shoot. This ensured that our muzzle flashes matched those captured on the day.

In one sequence, Al Qaida has attached an incendiary device to the base of a lamppost on the street, which detonates, resulting in a huge explosion which destroys a Bradley tank which is next to it. The explosion was captured using 7 camera from various perspectives and the VFX span four consecutive shots. The explosion was captured in camera using SFX, so it was necessary to add a soldier shot against bluescreen in. We’ve added the distant city environment in and distant houses, as well as removing all the cameras and equipment which can be seen in the wider shots.

Another notable explosion is the show of force; a military term for when a jet (in this instance, an F16) flies a low pass overhead to intimidate the locals. It’s a big, powerful jet, so it’s loud and dramatic. On the day we filmed the plate, live sound was played onto the set rumbled through the buildings and had a massive impact. We created a full digital F16 with a dust simulation. We referenced real jets and knew that a jet flying low to the ground would kick up dust, but that would not emerge until after the jet has lifted up, with its thrusters driving down into the ground.

So it was a difficult simulation to get right and we created it four times for show of force shots throughout the film – although we only see it from the front twice. We used a full model of the street based on a lidar scan, the model we built additionally to extend the street out into the distance. It needed to be plausible, with the interaction of the dust hitting the sides of the building, bouncing back into the set and how it’s lit. We ran the jet through the space in CG to get the simulation right. It was a heavy simulation, which took a couple of days to run and few chances to make amendments before delivering. One of the only “movie” camera moves.

It was a difficult simulation to get right but the simulation is physically plausible in that we used our street model. So we have a full model of the street based on a lidar scan and then the model that we built to extend the street out. So, all the interaction of the ground, of the dust hitting the sides of the buildings, bouncing back into the set, how the dust is physically plausible. And then we ran a jet through the middle of this to create the simulation.

Can you tell me more about the smoke, haze, phosphorus?

It goes back to that ISR. So, the explosion that’s been attached to the lamp post that goes off and when that expose it throws out phosphorus which go in all directions a little bit like a firework and these land on the ground. We investigated this they burn for something like a couple of minutes. During the shoot SFX placed a white burning light bulb, it was a little LED with some smoke coming off it in the same place on the set. So we had this continuity. We always had a white phosphor. At the end of the day we still ended up replacing those adding smoke to them and occasionally actually changing the phosphor glow.

The premise behind this was once the ISR explosion has gone off the soldiers are in this very confused state. they can’t hear, they can’t see, and the whole place is covered. We shot with quite a lot of smoke, but not enough for Alex and Ray. So, in post, we probably doubled or quadrupled the amount of smoke needed for the scene so the soldiers couldn’t see each other.

So in some cases they’re standing almost next to each other, but they can’t see each other. So we’ve used a combination of the SFX elements I shot against blue screen and then some of our own simulations to add smoke to that and then the white phosphorus smoke to finish. Furthermore, quite a dramatic grade takes place across that which reminds me of sort of mustard gas. The original footage is really quite bright and normal but where it ends up this sort of nasty green sludgy colour, a smoky colour. So, a combination of really heavy grade and… our doubled quadrupled smoke elements and that clears across 40 odd shots but never goes completely clear and that smoke lingers for the rest of the show pretty much then the Bradley’s (tanks) turn up a second time.

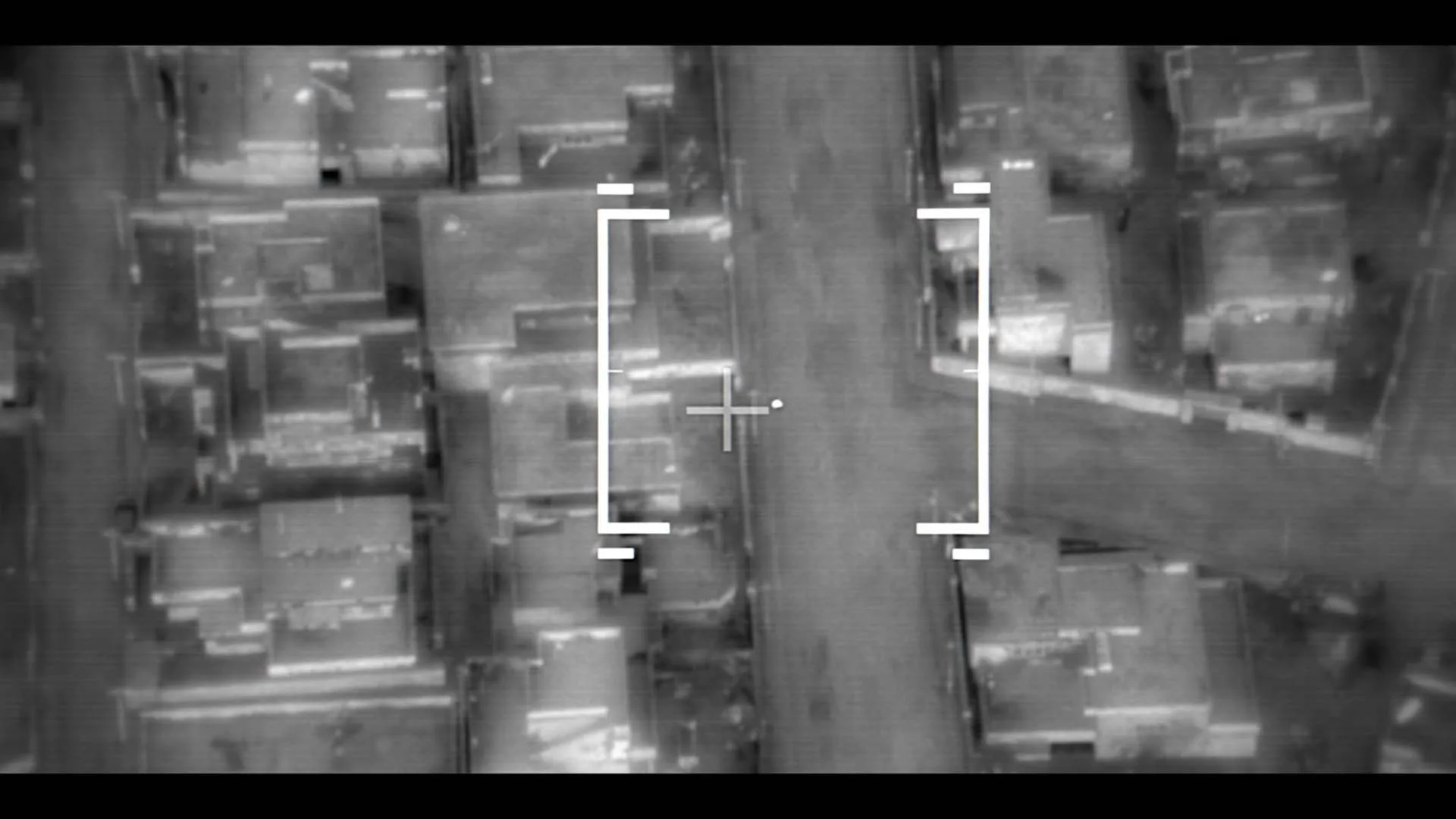

Can you tell me about the ISR / satellite type shots?

So the premise here is an observation plane circles over the target area constantly circling and they have the ability to zoom in on areas but the plane is always slightly rotating around and moving around. They can zoom on areas, target stuff, zoom out and look at specific things. So, we animated, maps to be used on set as live playback and that worked for a handful of shots.

The soldiers are interacting with a live laptop with a graphic playing out on screen. When we got into post by way of exposition really just to explain a lot more of the story the number of these type of shots grew. So we went from three shots to about 10 very specific action ones taking place on this ISR map. It’s an aerial view of our street and the surrounding streets using our 3D model. We’ve treated it very heavily to give it this ISR black and white, degraded TV look, very grainy, granular, and then added the graphics over the top of that.

The map had to be populated with people. We follow various people. You see kids playing etc, we needed life to go into these maps. Initially we talked about motion capture and hand animating because they’re very very small sprites. But the quantity and the reality of movement (even though they were going to be massively degraded and very small) that Alex wanted them to move like authentic people with the unpredictability of movement.

So, we looked into shooting that in the studio but couldn’t find a stage high enough to give us enough space for travel on this action. I did a whole bunch of simulations just to work out how big the stage should be and then suggested we shot it with a drone. So, we went back to Bovington airfield and we shot on the airfield this time, we were mercifully lucky with the weather! We had two days of brilliant sunshine.

I had a massive blue screen carpet laid out to mimic our street and shot the whole storyboarded of each of the seven different maps and seven different actions and we shot all the soldiers and about 20 civilians over the course of a day. There was a day prep set up and a day to shoot. Initially it was looking too clean for Alex and Ray. It’s not as he remembered, and I think the thing to be aware of here is this was 16 years ago. The technology is a bit fuzzy. We ended up degrading the graphics to a point where it fitted the story. We had some great feedback from the first screening because the audience thought that the ISR shots were real, which meant we’d done our job right!

We had a full Lidar of the set so all the buildings that are in the set, we had representation of in LAR and then where we’ve extended them, we have our own physical builds. Textures for those builds are based on the set. So, a combination of photogrammetry and stills were taken as texture reference. This ensured any of the buildings we took over matched the textures of the day and of the set dressing.

Can you tell me about the gore?

Prosthetics were used extensively for the damaged legs of our soldiers. Two of the soldiers suffer horrendous wounds so it’s a combination. There were holes in the floor of the main set building inside so once they’re dragged in back into the building to establish the extent of their wounds, there are trap doors in the floor. Their legs were underneath them and then prosthetic legs extended from the knees or hips of the actors. Those prosthetic limbs were severely damaged, covered in blood and guts and gore.

We enhanced a little bit of it, added some moving blood and a little bit of arterial pumping. But overall, that is all amazing prosthetic work.

What would you say was the most challenging aspect of the show?

I think the big show of force dust simulation because it’s such an unseen thing Alex described it as standing on the shore side and it should be felt like a big wave coming towards you. It’s not something anyone’s really seen or experienced, so it’s hard to gauge exactly what it should look like. But it shouldn’t look like a Marvel effect or anything unrealistic either. So yep, the big dust simulation for the show of force shots. Other than that, just keeping it real and supportive of the story and directors’ visions.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Cinesite: Dedicated page about Warfare on Cinesite website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2025