Scott Farrar began his VFX career with STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE. He joined ILM in 1981 and works on most legendary projects of the studio like the BACK TO THE FUTURE trilogy, WILLOW, WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT or JURASSIC PARK. As a VFX supervisor, he worked on movies like BACKDRAFT, MINORITY REPORT or the TRANSFORMERS trilogy. He received an Oscar for Best Visual Effects for COCOON.

What is your background?

I studied filmmaking at UCLA, and received my BA and MFA from there. After graduating, I worked as a freelance cinematographer and editor on industrials, commercials, ride films and films. After working on STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE, I realized I really preferred visual effects photography over live action. I was hired by ILM in 1981 and have loved the atmosphere there that allows us to experiment. Of course I’ve been part of the transition from photo-chemical to computer graphics, and that change has given us so many new possibilities for making great images.

How was this new collaboration with director Michael Bay?

I have fun with Michael. We both strive for great photography and we both place a great deal of emphasis on lighting, composition, movement, texture, color and mood. He gives me a lot of freedom to try things- if my crew and I come up with a good idea, it’s in the movie.

You supervised the two previous films. Can you tell us what are the major changes in this new film?

The goal with any sequel is to come up with new ideas, something you haven’t seen before. Early on I suggested we go to extreme-slow-motion, go darker and moodier in some scenes and try new ways to show the transformations. I think we did all these things I tried to improve the illusion of how real we could make our shiny metal robots, so we do many things to enhance their surface textures, colors and the way light reflects from their parts. And we re-work parts of their body and face to look « cooler » or to add different pieces to act better.

But the biggest change was to make this film in 3D. We shot a large part of the movie on stereo cameras, so when we make or render a robot for one eye, we must render it again from a slightly different angle for the other eye. That may sound simple, but by the time you finish putting the

shot all together, or compositing the shot, you will add 20 to 30 percent more work to the shot.

What was your feeling to find again these robots and Michael Bay?

It’s like working with old friends. We have really gotten to know these robots and their personalities to the point where we know how they should respond as characters. It’s exactly like working with actors, knowing their differences from each other.

How did you create and animate the impressive Shockwave?

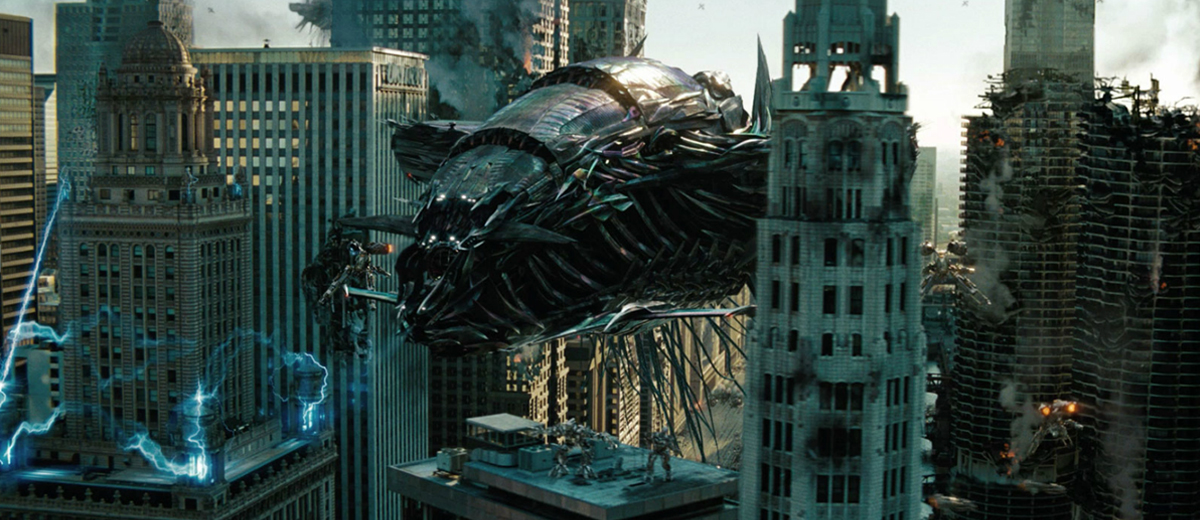

I think you mean Collosus, the 150 foot long snake-like creature. He was so complicated that he took 6 months for Rene, one of our best model-makers, to finish him. Animating him took longer because he had so many body parts.

Can you talk about his rig and the animation of its tentacles?

The hard part in rigging him is allowing the rings on his body and tentacles to spin as he moves across the ground or through the building. His animation and position on the building is done first, then we destroy the sections of the building where he is placed. That involves many computer-simulations: breaking glass, metal, cables, beams, smoke, fire, sparks, concrete, dust and liquid.

The render times for Collosus entwined with the Tilted Building were the highest in ILM’s history: 288 hours per frame! And that is just for one eye, and sometimes the computer would choke on a frame and we had to start over. That’s because both objects were reflecting the environment, and that is a complex algebraic calculation. To compare, the longest render on the last TRANSFORMER’S was 36 hours for an IMAX frame. Over 50 different specialists worked on this shot.

Have you developed specific tools for the destruction of so many environments? Such as warehouses of Chernobyl and Chicago?

Yes. Mostly, we shoot real locations and build from real photography. I shot aerial shots, or plates, from a helicopter for 6 weeks in Chicago, for instance. We also sent a crew from our Digital Matte Department to shoot a complicated assembly of all the buildings along the river in downtown Chicago, and 3 other areas as well. Our new tools are used to stitch 1000’s of photographs together to create a 3 dimensional virtual « city » in which we can fly or position a camera anywhere. It is photo-real, and you cannot tell it is a re-creation of buildings. It’s very cool.

Can you explain to us, step by step, the creation of the incredible shot where Shia Leboeuf is ejected in the air from Bumblebee on the highway and then finds himself back on board Bumblebee? How did you create it?

I knew I would need to photograph Shia for at least part of this shot, because digital doubles of actors still do not hold up well, especially in a slow-motion shot where you can study every emotion on his face. So, we flew Shia on wires in front of a bluescreen, and shot him at high speed. We also photographed a real location with the road and bridge for reference, using stills and movie cameras. And we shot a plate of Shia in the real car for the final part of the shot.

We built the background from the stills, changed the lighting, and created the camera move. Bumblebee was an animated car transforming into robot, then changing back to car, and with a wipe across screen, we end with Shia settling in his seat in the car. Real Shia switches to a DigiDouble when Bumblebee grabs him and goes into a roll. The bottle truck and all the gas bottles, debris, smoke, sparks dust flame shooters and broken glass are all separate animated elements. That’s it!

Robots are changing very often. Have you set up automatic transformations to help your animators?

No. All the transformations are custom, and are hand-done by very smart artists.

The fighting in hand-to-hand combat between robots are very numerous. How were they choreographed and how did you animate them?

On the first film, Scott Benza and Rick O’Conner, our Animation Supervisors, used reference footage from Hong Kong fight films. And Michael Bay shot reference with his stuntmen for us to copy, because our moves weren’t too cool yet.

On TRANSFORMERS 2, we were getting better, but we did have a stuntman come to our building to help shoot more reference with our animators.

On TRANSFORMERS 3, Scott and Rick were so good they didn’t need any help, and surpassed anything they had done before!

How did you create so much destruction in Chicago? What was the real size of the sets?

No sets. All real backgrounds with damage, fire and smoke tracked into the camera movement.

Can you talk in detail about the collapse of the tower cut by Shockwave?

The basic break and fracture is relatively simple. The body animation and speed of fall are worked on in simple form until it looks cool. Then the tentacle movement refined until it makes sense to camera. It’s the 100’s of layers of breakage and damage that make it look real.

What were your references for the many vessels of the film? How did you then designed and animated them?

The main production art department comes up with the designs. I think the big breakthrough was when our animators came up with the idea that the fighters could transform, just like the robots.

Some shots show dozens of ships and robots in the same frame. How did you manage so many elements?

One item at a time is placed, animated or moved, then we watch the shot and adjust speed, composition and number of elements based on composition.

How do you integrate your robots so perfectly in such a amount of explosions and dust?

Great artists do amazing things. We shoot everything, real, dirty, with lots of pyro and dust in the shots. We use roto to fit the robots in, and try intricate choreography to animate to the movement of the robots to fit in the plate. If the robot does not integrate well into the dust, for example, the compositor adds many new layers over the robot to give the illusion that our dust element is part of the original dust element. It’s a magic trick, really!

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

I always sleep well, just not enough hours sometimes. These movies are many months long, like a long-distance run.

Will your Singapore division has been working on this film?

They did more shots on this than in the past, over 150. The work was great. And they did just about everything in each shot, since they have increased their artist base.

How long have you worked on this film?

18 months, a year and a half.

How many shots have you made and what was the size of your team?

580 shots with 355 artists at the peak of production.

What do you keep from this experience?

You can accomplish a lot if you have great people on your team. And I did, I’ve worked with a lot of my crew on all 3 films. So we’ve built a lot of history, experience, ideas and reliance on one another. Creating things together is a thrill.

What is your next project?

Vacation!

What are the four films that gave you the passion of cinema?

THE 7TH VOYAGE OF SINBAD, BEN HUR, THE GREAT ESCAPE and THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY (one more FRANKENSTEIN!).

// A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE ?

– fxguide: fxguide article about TRANSFORMERS: DARK OF THE MOON

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2011