Prior to joining MPC Vancouver, Seth Maury has worked for studios like Warner Digital Studios, Cinesite and Sony Pictures Imageworks. His career counts films like HOLLOW MAN, BIG FISH, SPIDERMAN 2 or ALICE IN WONDERLAND.

What is your background?

I studied mechanical engineering in college and worked in product design for about 2 years before moving into visual effects. I first worked as a compositor at RGA Los Angeles, then Warner Digital Studios and Cinesite Hollywood. I then moved to Sony Pictures Imageworks, where I stayed for 11 years and worked as a compositor/lighter, CG Supervisor, and DFX Supervisor. Currently, I’m a visual effects supervisor at MPC Vancouver.

How did MPC got involved on this show?

MPC had worked together with Chas Jarrett, the show VFX supervisor, before on a few shows, so Chas was familiar with MPC’s abilities and strengths. For SHERLOCK 2, Chas was very interested in our in-house destruction tool Kali, that can produce very complex physical simulations, and which was a good fit for the work, such as the watchtower destruction.

How was the collaboration with director Guy Ritchie and Production VFX Supervisor Chas Jarrett?

Chas was great to work with, he had some areas where he was very specific, and other areas where he gave us a lot of creative freedom to develop the environments and ideas for shots. Chas always has a strong focus on the intent of the shot, is it telling the point it needs to? is it giving the appropriate sense of time period and ambience? Guy has a lot of confidence in Chas in that same manner, he knows what the shot needs to convey, and for Guy, the shot either works or it doesn’t.

What have you done on this movie?

MPC worked on approximately 400 shots across 10 sequences, the main sequences being Baker Street, Paris Opera House, and the Factory Complex/Forest Escape.

Can you explain to us in details the recreation of Baker Street?

The precedent for the look and feel of Baker Street had been set in the first movie, so we had to be faithful to that same feel while working on views that hadn’t been seen in the first movie. The most complex Baker Street shot was the establishing wide shot that ran after the main titles, where we start looking across the rooftops of London and crane all the way down to street level to find Watson walking up to 221 Baker St. We started with a live action plate shot at Leavesden, with a partial set piece for the front of the building. We also shot some motion control elements of people and horse and carriages to dress along the second block. We also had an art dept layout of the intended look and feel, so we photographed many buildings around London that we could use for source texture. We modeled about 20 CG buildings that we used to extend the street, as well as some digital matte painting and projection work to take those models further. The opening wide vista was a mix of 3D buildings, 2.5D projection, and 2D paintings for the very distant buildings. The cloudy sky is a panorama that I shot from my balcony here in Vancouver. The clouds here in Vancouver have a different feel than those in London, so we worked on the pano in comp to give it a London feel, but also to retain a sense of drama. The art dept was very specific that the wide vista of London have little to no trees, and very few white window frames, all in keeping with the Sherlock feel. Then the entire shot was brought together in comp with a lot of effort and balancing and sorting of technical issues from bringing elements from so many different sources together.

What were the real size of the sets for the sequences in Paris, and how did you create those huge environments?

It depends on which angle you’re looking, but for the most part, the sets were small sets built for the actors to be on, and then we built a CG environment around them. For example, the shot where we follow Holmes and Watson out of the Opera House towards the Hotel was shot in Greenwich, and the only building we kept from that was the door and surrounding stonework from which Holmes and Watson run out from. The square was then made up of CG buildings built from reference and measurements of the practical buildings around the actual Opera House, but we then changed the geography and layout to make it feel smaller and more intimate by taking out some roads, and moving the buildings in tighter. The rooftop set was a practical set piece about 20 feet long, which we then extended in CG, based on photos we took on the actual rooftop of the Opera House. For example, the shot where we crane up over Holmes, Watson, and Sim was only a big greenscreen and nothing practical to anchor that wide vista. We populated the square with digital crowd and horse and carriages, as well as period-appropriate street furniture and lighting fixtures. We also photographed awnings, doors and restaurants all around Paris, trying to find the elements that still felt period, and then we built the lower floors around the square made up of these different practical pieces we found.

How did you take the references?

The references were mostly shot by our in-house MPC photographers. We shot as much as we could from as many angles as possible. For example, we got permission to shoot on a scissor lift in the area and roadways in front of the Opera House, so we covered it from different heights and different angles all around, and we were lucky to be out there on very overcast days, so we didn’t have to paint out hilites and shadows from the sun.

Can you tell us more about the explosion at the Hotel du Triomphe? Did you used pratical elements?

The hotel explosion was made up a mix of practical elements and a cg building. We shot 2 different explosion elements that we planned to use, but they ultimately didn’t work well enough to sell the explosion. We ended up using layered library-element fireballs and we modeled a CG version of the 2nd floor upwards of the Hotel and married that with a practical plate of the ground floor. Having a CG building allowed us to get a lot more accurate interactive lighting on the building. Initially we thought these shots would not be too difficult, but they ended up being some of the more challenging ones to sell in terms of impact and reality.

How did you create the Opera House and populated it?

We weren’t allowed to film inside the Opera House, so Chas designed the shots to be filmed on a set piece with environment set extensions. We were allowed to take photo stills inside the Opera House, so we shot panos from multiple locations on the stage looking out, and from the audience looking back. We built a 2.5D environment inside of Nuke with those high rez panos and some basic interior geometry. For the crowds, we filmed shot-specific crowd elements on a riser. The riser was fixed in place and we moved the cameras around the stage to get the different crowd plates we needed to build a full auditorium of people.

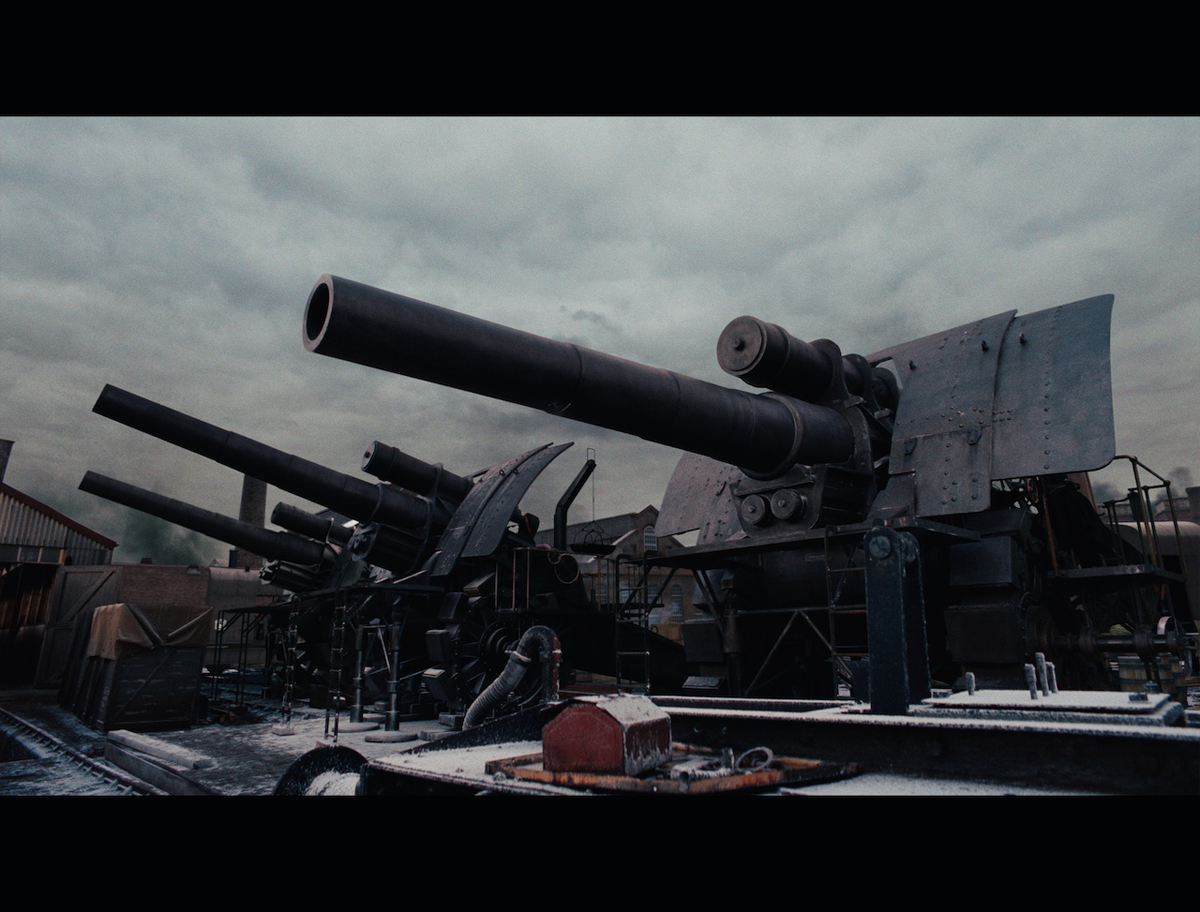

Can you tell us more about the creation of the huge weapon factory?

Most of the shots were made up of practical location plates with cg set extensions. We had a mixture of wide establishing shots and tighter set extensions. The work was in 3 main areas: the firing range and watchtower, the rail yard, and the approach to the factory. When I first met Chas, one of the first books for reference he showed me was about the Krupps factory, filled with pictures of how the factory evolved over decades, organic in shape and layout, and also descriptive of how it was essentially its own functional town with living spaces, tailors, food stores, etc. Our goal was to recreate this organic feel, to make our factory feel as if it had grown over years, and was a fully functioning small factory and city. So in our wide layouts we had areas that were more concentrated with industrial type equipment, furnaces, smokestacks, large warehouse type buildings, and then areas that were more living quarter type areas. We built about 20 cg buildings to different levels of detail, that we used to dress the different views, both wide and tight, along with many street props, furniture, and signage. Our cg buildings were all based on practical factory buildings that the art department had scouted at Sleaford Maltings, Bollwiller, Bitterweld, Dessau and Chatham Docks. Our MPC photographers photographed them in detail and then we recreated them in cg, some as full 3D models and some as more simple 2.5D buildings.

For the watchtower, we had concept art from the art department, as that building never existed practically in a location, though we had a partial set piece that we had to be faithful to. In general, for the look of the factory, we went through a lot of different permutations of a factory that was thick and dense and overhung with smoke to more thin, vast spaces with overcast semi-oppressive feeling skies. This was an area of exploration that evolved as we worked with all the different location plates, as we had to find a consistent look and feel that would work for al the practical photography. I definitely had a stage where I went over-the-top with smokestacks, the factory had veered into looking like a concrete forest, but it was all part of the experimentation.

Some shots involved impressive destruction elements. Can you tell us more about the use of Kali for those shots?

Our biggest destruction shot was the watchtower falling over after it had been hit by the Big Bertha shell. This was an all cg shot. From the early previs, we had an idea of what the shot needed to be and how it would be framed. We knew we needed to sell the scale and weight of the tower going over as it crashed into the Surgery building. Both the watchtower and the surgery building were modeled to be Kali friendly, and our fx lead Georgios Cheruvim, first started with simple geometry representations to get the timing and blocking right, and then we progressively refined the sim to get more detail. Chas was good in pushing us towards practical reference of the way smokestacks seem to bend over the length before they start to give way locally. Once we were about 90 percent happy with the general motion of this shot, we then started working on the smoke, which I felt would really be the thing that helped give a sense of scale and weight to the shot. We studied a lot of reference of building demolitions and we noticed how strong, violent and dense the first rushes of dust and debris were from impact, so we aimed to recreate that feel in our cg smoke.

How was filmed the impressive slo-mo Forest escape sequence?

The forest footage was shot on a Phantom camera, upto approximately 2500 frames / second. The editor would take the raw footage and give us mockups of the retimes he wanted, which we would match to. For some of the shots where we punch in and out in the same shot, Chas used 2 Phantom cameras mounted side by side on a speed rail, one with a wide lens, and one with a longer lens, and then we again matched the mockups the editor created to mix between the plates and then we smoothed out those transitions in comp. In addition to the raw footage, Chas shot Phantom elements of mortar and dirt and trees exploding, that we then mixed into the plates, which already had some of those effects as practical special effects. We also had practical Phantom bluescreen elements of bullets hitting wood trees, some of which we used, and then we also created some cg bullets for some shots and augmented the destruction with the bluescreen tree elements. Our comp supervisor Mark Richardson handled a lot of these shots.

Did you encounter some troubles with those slo-mo footages and Kali?

One of the slo-mo shots in the forest involved an exploding cg tree, which we used Kali for. The shot went through exploration until we landed on the shot that’s in the movie, but we decided early on that we would simulate and render all of the frames so that we could do repos and retimes in comp to make the turnaround quicker. This meant that we were rendering thousands of frames, most of which were discarded once the retimes were applied. Shots that long usually have issues even if only because they are so resource intensive.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

The most challenging aspect of our work was in convincingly recreating the wide vistas of period London, period Paris and the wartime Factory, both daytime and nighttime. We had to pay attention to all the macro ideas and concepts and more specifically to all the small details that ultimately help sell the shot, such as roof material types and construction, chimneys, city density and layout, lighting sources available at the time, appropriate street and building signage, for example. These types of shots involve first a lot of research, and then continuing research throughout the entire pipeline, as different details become relevant as the shots progress..

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

There was a period during post production where we had been working on the Opera House square and trying to do a lot of that work as 2.5D projections, but we realized that we needed to go back and do full 3D builds of those buildings to really get the flexibility and look we needed. That kept me awake a few nights.

What do you keep from this experience?

I learned a great deal about set extension work. I had previously done lots of creature and character work and some cg set recreation, like the city work on SPIDERMAN 2, but for this show, there was more variety of set extensions and they were also not meant to be present day, so it was not as immediately familiar as other set extension work. Also, it was great to work with Chas and Laya Armian, the show’s VFX producer, as they made it a very enjoyable experience for me.

Which branches of MPC have worked on the show?

MPC Vancouver, MPC London and MPC Bangalore

How long have you worked on this film?

I worked on the film for a little over a year.

How many shots have you done?

MPC worked on approximately 400 shots across 10 sequences, the main sequences being Baker Street, Paris Opera House, and the Factory Complex/Forest Escape.

What was the size of your team?

The main production team was made up of Doug Oddy, our in house producer, Danielle Kinsey, our in-house production manager, and Jennifer Fairweather, our show coordinator. Our compositing supervisor was Mark Richardson. The artist team consisted of approximately 30 compositors, 10 lighters and look dev artists, 5 texture artists, 12 DMP artists, 5 modelers, 5 fx artists, and approximately 75 people comprising roto, rotomation, matchmoving and paintouts, spread between Vancouver, London and Bangalore.

What is your next project?

Thats confidential, stay tuned!

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

JURASSIC PARK, first and foremost. I was working as a mechanical engineer at a product design firm, and I went to see JURASSIC PARK and had that moment of « Holy s**t, how’d they do that? » And so I quit my job shortly after that and eventually found an entry level job at a VFX company. Otherwise, as for movies, it’s probably the original 3 STAR WARS movies. Again, they were something that people hadn’t seen before, and on such a grand scale.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– MPC: Dedicated page about SHERLOCK HOLMES: A GAME OF SHADOWS on MPC website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2012