In 2013, John Knoll told us about his career and PACIFIC RIM. He then oversaw the effects of TOMORROWLAND before taking care of the new STAR WARS movies. Today he talks about his work on ROGUE ONE.

What was your feeling to be back in the Star Wars universe?

It was really fun. I have a great love for the original trilogy, and A NEW HOPE in particular. It came along at a time when I was starting to think seriously about what I was going to do with my life, and A NEW HOPE pushed me over the edge to go into entertainment instead of some more reputable field.

I had the wonderful privilege of working directly with George Lucas for many years as part of his team on the prequels, but being able to go back and make something that fits into my favorite film was especially rewarding.

You have wrote the story of Rogue One. How did you find this idea?

The core of the idea comes from George Lucas and the first two paragraphs of the crawl of A NEW HOPE. I’ve always thought that would be an interesting story to tell. I elaborated on that and built it into a more complex and fleshed out story with characters. As we got further into development and production, a number of other writers further matured this idea, adding new characters and events, eliminating others, evolving it to the story you see today.

You are also producer of the movie. How does that changes your work as VFX Supervisor?

The Executive Producer title can mean a lot of different things in the film industry, everything from being intimately involved in every detail of how the film is made to it being a largely honorary title with no real responsibilities. For me it meant participation in many other aspects of the production than I usually do when I’m just VFX supervising. It was a very interesting process. Of course, my role as VFX supervisor is one I’m very familiar with and is right in the center of my comfort zone.

How was your collaboration with director Gareth Edwards?

As usual, my role is to try to mind meld with the director and to use that understanding to help him realize his vision for the film. You try to get to a place where you can predict Gareth’s reactions to everything.

What was his approach about the visual effects?

Gareth brought a documentary style to the film, one that generally eschewed planning things out in too great a level of detail. Sets were lit often so that we could look in any direction at any time, and Gareth would often run the camera for 20 minute takes where he would reset the actors again and again, finding new compositions. That meant that the first time I saw the challenges of a shot was while we were shooting it and it was a little too late to bring in a bluescreen or add some tracking markers. I’ve always tried to make sure VFX maintained a small footprint on set and that we don’t put unnecessary constraints or delays on the shooting. I try to work unobtrusively with the rest of the crew to make sure the right things happen and we get what we need out of each setup. Gareth trusted that we would be doing that and he could ignore the VFX aspects of what we were shooting. If I had an issue, he knew I wouldn’t be shy about bringing it up.

How did you organize the work amongst the VFX supervisors at ILM and your offices?

ROGUE ONE was a relatively large show and ended up being fairly backloaded, meaning most of the real heavy lifting of shot production occurred in the last 3 months or so. We tried to divide up the work to minimize duplication of effort, since every sequence requires some art and technique development to make them work. Mostly we split up the work by planet. For example, San Francisco did the opening flashback planet, the asteroid city, the Death Star, Mustafar, the space battle, and we split Scarif with Vancouver. Vancouver did Scarif, Singapore did Eadu, and London did Jedha.

We also sent work to a number of other vendors. Hybride did the data vault, Ghost did much of Yavin, Whiskytree did Wobani, Atomic Fiction helped with Mustafar and Scanline helped with Jedha.

As far as the Supes go, Mohen Leo supervised the work in London as well as the post-vis effort. He helped me cover the shoot during principal photography when there were two units shooting and I couldn’t be in two places at once.

Nigel Sumner was my right hand man in San Francisco. He supervised Vancouver, Singapore, and Ghost. He filled in for me whenever I had to be out of town and did a lot of the detailed follow through of high level direction that I provided.

Dave Dally in Singapore did the heavy lifting over there.

Craig Hammack came in for the last few months to supervise the work at all of the other vendors.

How did you work with Neal Scanlan and his team for the creatures?

Actually, there wasn’t that much to do. Most of the work was in discussing approach when Gareth or Neal had an idea that was a hybrid approach where Neal would build something that needed VFX augmentation. Most of those were simple paintouts where a given creature was rod puppeted, or part of the performer in the suit needed to be painted out to complete the illusion.

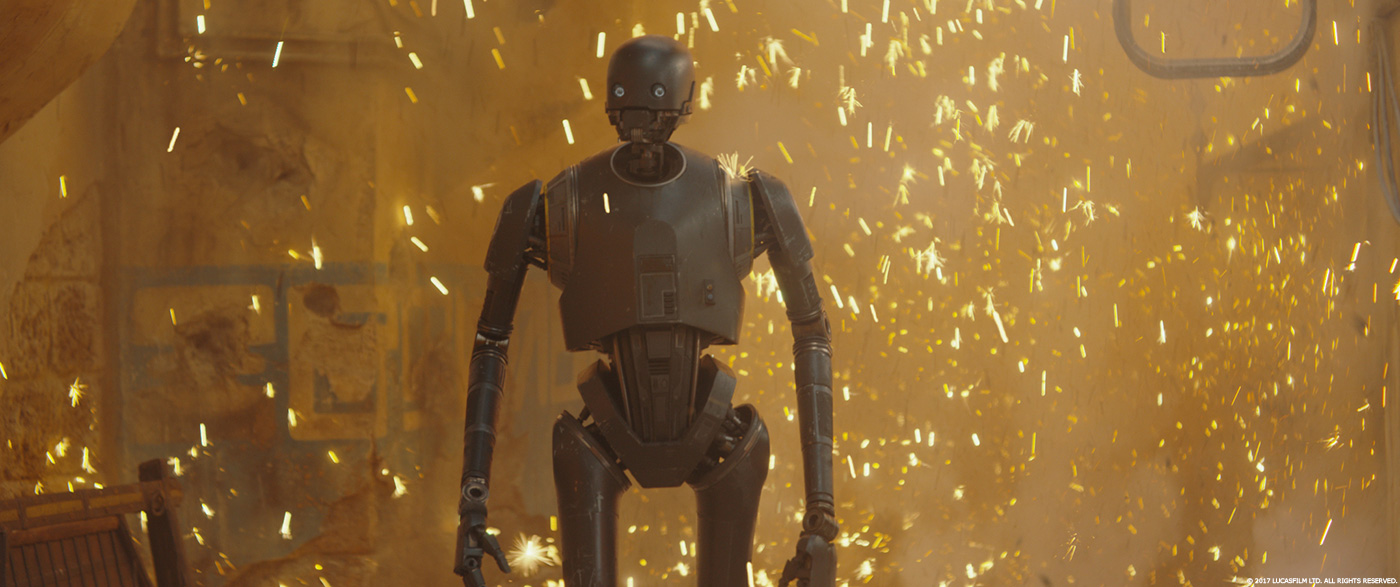

Can you explain in detail about the design and creation of K-2SO?

The Design came from Neal’s shop. They built a full size maquette as lighting reference, but it doesn’t appear in the film. There had been talk in preproduction about building a head and shoulders puppet and doing close shots in camera, but in the end it looked like it would be more trouble than it was worth and K2 would always be CG.

I felt very strongly that like we had done previously with Davy Jones, the best results for CG characters result from a close partnership with a great actor who is there to play the role on set. In that regard he was done exactly like Davy Jones. Alan wore an ILM iMocap suit and these amazing motorized stilts that Neal’s group came up with, and acted the role just like any other member of the cast. Alan’s a fantastic improvisational comedian, and many of K2’s best moments were ad-libbed. That kind of spontaneous and wonderful interaction can only happen when you create the right conditions for it, and having a CG character there with the rest of the cast allows for that.

The movie was filmed in various places like Iceland or Jordan. Can you tell us more about these shooting places?

The first day of shooting was in Wadi Disa in Jordan, right next to Wadi Rum where LAWRENCE OF ARABIA was shot. It was astoundingly beautiful. Really magical.

The Iceland shoot was pretty amazing as well. Iceland really looks like an alien planet with all of the jagged black volcanic peaks and the bright green moss clinging to the inhospitable surfaces. It rained pretty much the entire time we were there, so that made the shooting miserable, but it fit the mood and tone of that part of the film and thus was probably fortunate.

We also shot in the Maldives for parts of Scarif. I’d never been there before, and it was amazingly beautiful. In some ways it was like the Caribbean where we shot on PIRATES, but it was all flat. There are no parts of the Maldives that are more than two meters above sea level.

Many iconic vehicles are back like the AT-AT, the TIE fighters and Star Destroyers. Can you explain in detail about their creation?

That was a big part of the fun of this movie, striking a balance between the new and the old. I think the designs for those old ships were just brilliant and couldn’t be improved upon. We extensively photographed and scanned the original models out at George’s archive building, and that was a real treat just in itself.

From there, we tried to make our CG versions of them be the way you remembered seeing them even if it didn’t match exactly how they really were. An example of the is with the Star Destroyer. There were two full miniatures built of the Star Destroyer: a three footer for A NEW HOPE, and an eight footer for THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK. The models are somewhat different in their details. In principal, because of the era, we should be matching the three footer from A NEW HOPE, but that model is only really detailed on the underside. It also doesn’t have internal lights.

Everyone remembers that Star Destroyers have extensive portholes, docking bay lights, and midline trench lights, but those were all features of the eight footer from THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK. We built a hybrid that possesses the salient features of the three footer, but also includes the lights and better detailing you think you remember it having.

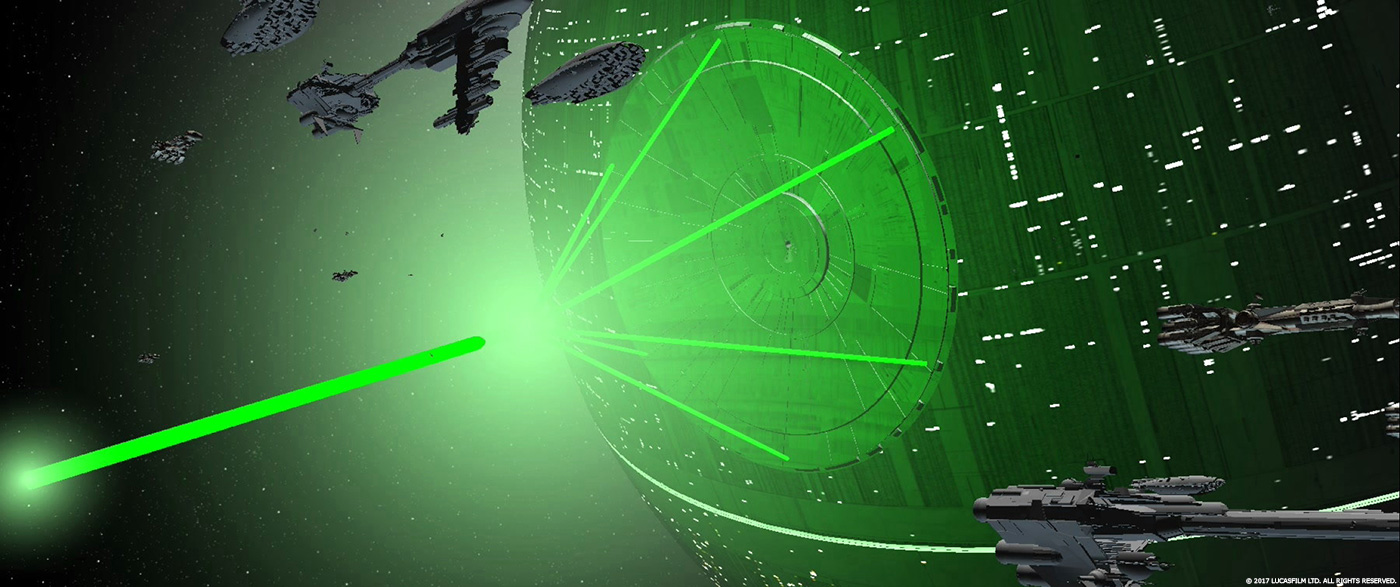

Can you explain in detail about the Death Star creation?

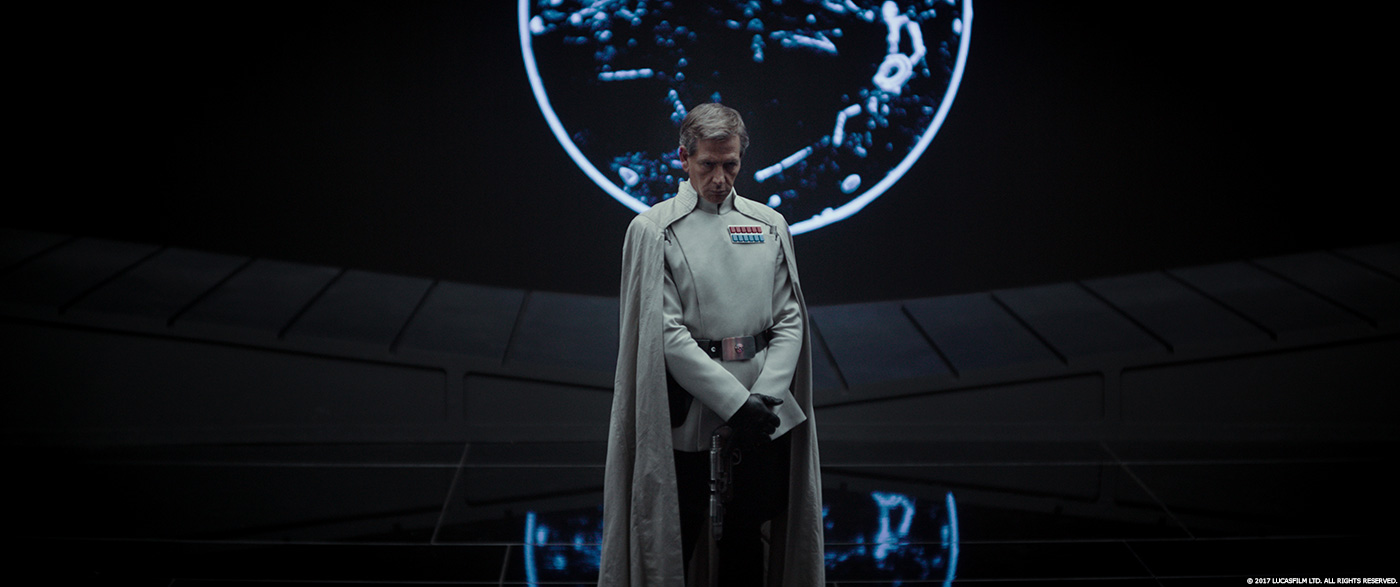

We built three scales. One was a full sphere for wide shots where most of the detail is just in texture maps. We built a medium resolution version used for shots of the superlaser dish being lowered into the Death Star that included modeled panels, and we built a super closeup section of the equatorial trench and the surface around the laser eye for the shot of Krennic departing for Eadu. That last version was a surprisingly difficult task, since it meant fusing the aesthetics of the wide views with the very close and trying to make it all feel consistent and true to the McQuarrie design style.

How did you art directed the massive destructions caused by the Death Star?

From a story perspective we had a requirement that the low power shots needed to take some time to develop and spread so our characters had time to react to it’s approach. The image we had in our minds was one of dropping a large rock into a pond and the wave that spread from that being made of broken plates of rock, eventually forming a “surf wave” of earth. We also included large static lightning bursts like you see around volcanoes to add to the nightmarish and apocalyptic feel of the scene.

For the Scarif shot, we wanted that to be a balance between the knowledge that the approaching wave meant certain death, but also that it represented in a way our heroes transcending and wanted to be etherial and beautiful. We justified the difference in look because the Scarif shot hit in deep ocean, so much of what you were seeing was water vapor and tidal wave.

Darth Vader has an impressive sequence at the end. How did you enhanced this fight?

Most of that was in camera. We added blasters, sparks, Vader’s sabre, wire removal, etc. Relatively minor stuff.

What do you keep from this experience?

We had a great crew, and they were a joy to work with. Every day they were creating amazingly beautiful work. It was like opening birthday presents every day. Such a privilege.

How long have you worked on this film?

I first pitched the core idea to a friend of mine at ILM a little over four years ago.

How many shots have you done?

We did 1697 “real” VFX shots. That’s not counting what we called “fixits”, simple paint outs, reframes, etc. There were a few hundred of those as well.

What is your next project?

I don’t know yet. We are talking to a few filmmakers about their upcoming projects, but nothing is set yet.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

It’s hard to narrow it down to four, since there are dozens, but probably the top four are:

FORBIDDEN PLANET, 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, STAR WARS: A NEW HOPE and ALIEN.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Industrial Light & Magic: Dedicated page about ROGUE ONE – A STAR WARS STORY on ILM website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2017