Pete Dionne has been working in the visual effects for over 16 years. He took care of the effects of many films such as THE LONE RANGER, ELYSIUM, 300: RISE OF AN EMPIRE or THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2. As a VFX Supervisor, he worked on GOOSEBUMPS and then PASSENGERS.

What is your background?

Prior to VFX supervision, I was a CG supervisor at MPC for several years, and a CG generalist at Technicolor before that.

How did you and MPC got involved on this show?

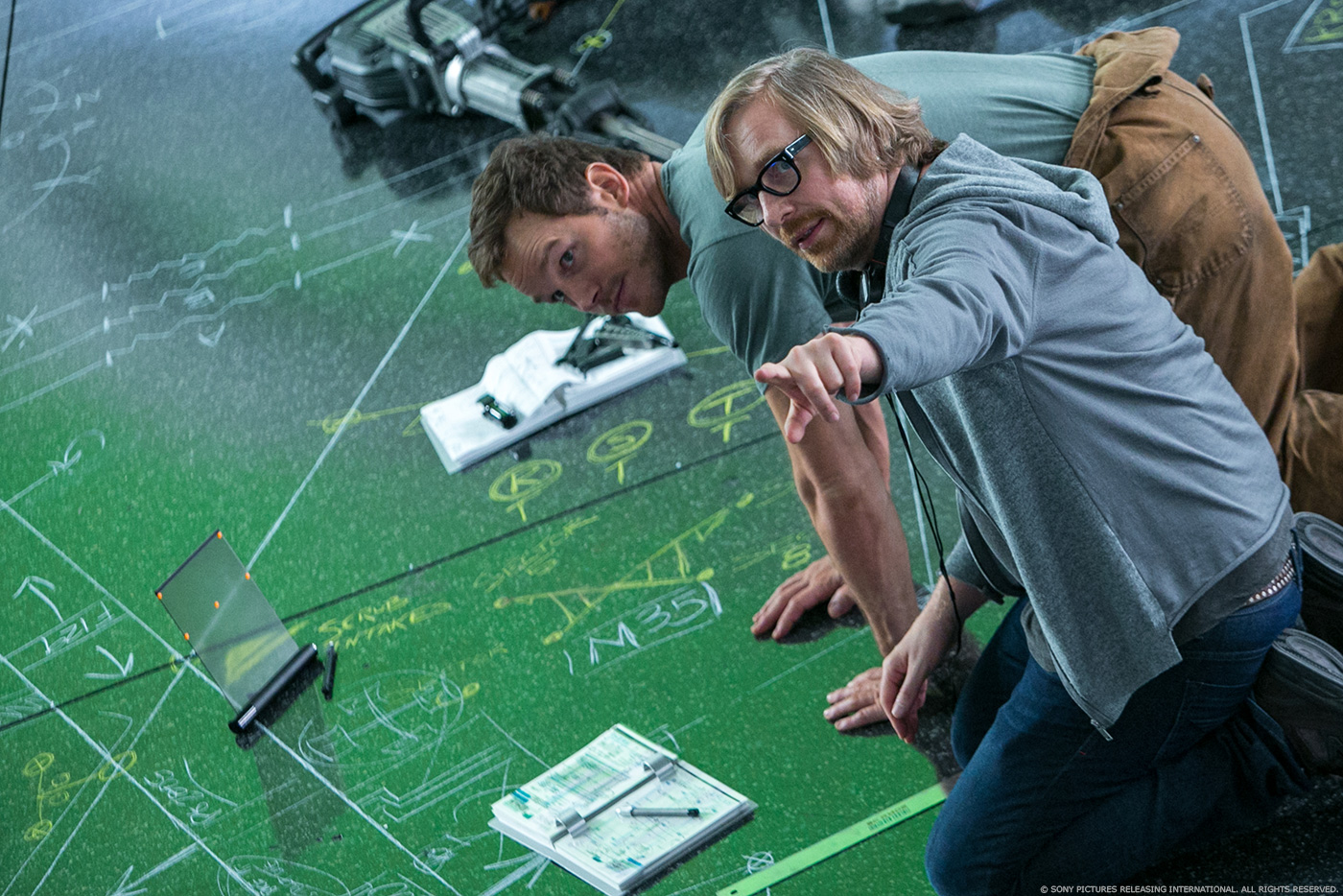

MPC’s involvement with PASSENGERS began in the spring of 2015, after production VFX Supervisor Erik Nordby and Director Morten Tyldum met for the first time and immediately formed a bond over a shared vision for the film’s visual effects. From there, I was brought onto the project as the vendor-side MPC VFX supervisor, to lead the teams in London and Bangalore. Erik and I have worked on several films together in the past, so it was a natural fit.

How was the collaboration with director Morten Tyldum?

Morten was great to work with. He’s a very open and trusting collaborator, always encouraging new ideas and outside input, but without compromising his own vision of the work.

That’s his first big VFX movie. How did you help him with that?

The great thing about Morten is that he always has his eye firmly planted on the big picture, which to him is constantly reinforcing story, character, and themes. From the very beginning, he put his trust in us to run with the minutiae of the visual effects development, yet still lead us on a high level by ensuring that every detail had a purpose, and existed in support of the story he was trying to tell. He is also a quick learner, and he picked up the nuances of the VFX development process very quickly.

What was his approach and expectations about the visual effects?

For every sequence, every shot, every detail in the frame, Morten was always clear on what the purpose and impact would be to the story. He would first figure out what he was trying to achieve, followed by figuring out the specific details or visuals after. His aesthetic definitely biased towards invisible effects, and where they couldn’t be invisible by nature, to keep them restrained and to never distract from the drama. All of this was great for us, as despite his initial inexperience with visual effects, it became easy to anticipate his direction.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer and the MPC team?

MPC took on around 1150 shots, which was a significant number considering how lean the budget was for what Morten required us to achieve. The first thing that MPC Producer Tomi Nieminen and I did was break down the shots and identify the groups of work which required the most design or technical development. Despite when the work was turning over in the schedule, we wanted to maximise the time spent on the most important and challenging work, such as the zero gravity water sequence, and of course the Starship Avalon. There was also so much design work to be done on this show; we had to be very diligent in scheduling out the work which required a lot of creative and subjective development in parallel with the sequences with much more clear and established targets, to avoid any major slow-downs or bottlenecks at any point in the schedule. It was a complex show from a project management point of view!

Can you describe to us one of your typical day during the post?

Like any film of this scope, it involved spending a lot of time sitting in a theatre, developing, strategising, and reviewing key work. I was located in London during post, so my day was mainly dictated by the overlapping of time zones with the other locations involved in the show; my mornings would be primarily focused on working with key team members in our Bangalore studio, my afternoons would be focused on working with key team members in our London studio, and then the evenings would be spent remotely reviewing and developing the work with Erik and the other filmmakers in LA.

How did you work with the art department for the beautiful spaceship Avalon?

MPC inherited an amazing design for the Avalon by production designer Guy Dyas, who was responsible for the clever rotating helical blades that encase the mechanical core of the ship. Our job upon receiving his design was to further embellish the ship with additional detail and design logic, which was in itself a mountain of work for a ship of this scale.

Can you explain in detail about the creation of the Avalon?

Our first task was to position all of the practical and digital sets inside of the Avalon, of which there were around forty. This formed a base logic and purpose for each component of the ship. For example, of the three blades, one was dedicated to habitation, sharing many design qualities with large cruise ships, one was dedicated to entertainment, sharing qualities with mega malls, and the last blade was dedicated to shipping, it’s form influenced by large shipping freighters. All of the sets relating to crew, like the bridge and crew hibernation, for example, took place in the front halo in the centre of the ship. The engine and power centre was located in the middle of the ship, with zero gravity elevator shafts connecting all components together. I could go on and on about the logic in the design; we spent the first two months of Avalon development strictly focusing on this, and it really paid off once we took our development to the next level, for both holistic and granular details of the ship.

Once this was completed, the next step was to model these details to a rough blocking level, led by Asset Supervisor Lisa Gonzalez, so that they could be discussed and developed in a three dimensional manner. This also allowed us to render still frames of this grey model and then paint finer details overtop in Photoshop, to help visualise the look of the final ship. Morten responded quite strongly to these paint-overs, which gave us the confidence to move past the conceptual stage and into proper asset development, which was an additional 5 month process of modelling, texturing, rigging, look-development, and finally lighting and comp templating.

Can you tell us more about the animation of the many parts of the ship?

The animation of the ship itself was quite straight forward, actually. Due to it’s speed and scale, we animated the world moving past the ship, with the Avalon locked at origin. The outer blades rotated at 1.8rpm to create 1g of artificial gravity, while the inner core rotated in the opposite direction at 3.6rpm, both for artificial gravity, as well to counteract and stabilise the momentum of the blades. So once this was established, it was set up as automatic controls in the rig and only required minor bespoke shot work by Animation Supervisor Gabriele Zucchelli and his team of animators, which was great, as they had their hands full with animating the complex movement of the cameras, characters, and tethers.

How did you manage its lighting?

Lighting the Avalon presented several challenges to us, both on set and in post. First, this film takes place in deep space, 30 lightyears from our sun, so Morten wanted the lighting design to reinforce how distant and isolated the ship was during this point in it’s voyage. This immediately disqualified using NASA photography within our own solar system as visual reference, as this has a very high contrast light from the sun which we needed to avoid.

It was clear that we had to invent a lighting design for deep space, but to keep it photographically plausible, so we looked to other real-world references for inspiration. We ended up taking several queues from photography of glass skyscrapers at dusk; as much as possible we would position the dark ship against the exposed band of the Milky Way to give it a strong silhouette, we motivated a very slight and cool ambient light from the distant space detail, we made the shaders of the Avalon very shiny to allow the reflections of space to provide definition of the ship’s form, and finally, we allowed the warm glow of the thousands of over-exposed windows and exterior lights to provide pockets of localised lighting, to support the overall scale of the ship and provide further fine details.

The spaceship is a massive asset. How did you handle the render challenge?

CG supervisor Sebastien Gourdal identified early on that with an asset of this magnitude, we had to be extremely diligent during it’s development, to avoid creating a beautiful but unrenderable starship. Essentially, his strategy was to cap the level of overall detail on the ship in modelling and texturing, to the top limit of what could be reasonably rendered, and work back from there. For all of the sections of the ship that the camera was very close to, we treated as additional environment assets, which were all built for specific shots and would be layered overtop of the main ship renders. This allowed us to go to town on the bespoke detailing, without compromising the render times of every other shot in the film. But even with this approach, it was still a huge challenge to manage the rendering of this asset, which required a constant and ongoing process of optimisation on every front.

How did you created the space environment and especially the Red Giant star?

To create space, Environment Supervisor Marco Rolandi and his team started with high-resolution maps of our own Milky Way, and used that as a base to build upon. We rebuilt all of the accumulated gas and distant nebula around the main band of the galaxy, and then embellished the front facing and back facing features, while maintaining the familiar gas structures that we see in long exposure photography of our galaxy. By layering space up in this way, it gave us full control to rebalance the exposure and grading of the gas layers per-shot, depending on the tonal requirements of the scene. We also rebuilt the stars into several planes of depth. The Avalon is travelling at half the speed of light, and we found that just the slightest amount of parallax between layers gave us a subtle sense of directional travel. Furthermore, layering the stars in this way also gave us some great depth in our native stereo composites of the exterior shots.

The red giant star which the Avalon slingshots around was a visual treat for us to work on. We referenced NASA photography of our own sun for both the look and the structure of the star; we developed an animated DMP map for the photosphere, then volumetric chromasphere and corona FX elements layered on top, and then further simulated erupting prominences similar to those found in the sun. One additional layer we recreated for our red giant star were visible magnetic rays arching across the entire star. Technically, these can only be seen outside of the visible spectrum of our own sun, but they’re so beautiful that we couldn’t resist sweetening our star with this element.

Inside the Avalon, there are many rooms. Which one was the most complicated to created and why?

The Grand Concourse, which was a massive build for us. The practical set itself encompassed the entire ground floor of the main area, so we had that to use as an initial structure to base our design and modelling from. We had to build extensions of hundreds of meters in both directions, as well as six stories up. The main concourse had a very minimalist design, but we were still required to build dozens of full CG storefronts, as well as furniture, holograms, and hanging banners, with enough variations to fill the entire space. Once we had the entire CG build assembled, it was quite a complete and cohesive digital set. This allowed CG supervisor Audrey Ferrara to have her team position cameras through the digital set and render them for comp, with very little bespoke shot work needed. It took many months across several departments to achieve this build, but the end result looks great.

Can you explain in detail about your work on the bartender Arthur?

Special Effects supervisor Dan Sudick built a great rig for Michael Sheen to kneel on, with additional rigging to support his back and keep it straight as he quickly slid back and forth along a track. The rig itself was very impressive. In VFX, we were tasked for a combination of rig removal, stabilisation, and retimes from the waist up, then building the CG structure below the waist which supports Arthur in the film.

There are many Zero G shots inside the ship. Can you explain in detail about their creation?

There is one great scene where the gravity cuts out as Jim and Aurora are running across the Grand Concourse. First, Jen’s stunt performer and Chris were swept up into the air and dropped hard down to the floor at full speed, to achieve the desired stunt. Jen was then strapped into the stunt rig and acting through the same stunt at half speed, to achieve the required performance plate for her face replacement. To drive home the point of gravity loss and then restoring, we also filled the environment with CG furniture and robot debris, as well as the fountain with CG water, which we then ran simulations on to achieve the desired gravity effects.

How did you created the digi-doubles of the actors?

We built CG digi-doubles for medium and wide shots of the actors in various costumes, which were created from great photogrammetry models provided to us from the folks at Captured Dimensions. For any close up shots of the actors which couldn’t be achieved in camera, we shot performance plates using a three-camera array and relied on facial projections. For all of the spacesuit replacements, the material from Captured Dimensions as well as our own polarised texture booth photography was enough to recreate the suits digitally at a very high resolution, which we relied on a lot on this show.

Can you explain more about the impressive Zero G pool sequence?

We knew this was going to be a real challenge from the start, so we immediately began R&D simulations in FX to see how water would actually behave in this environment. What we found was that at this scale, the water would move so slowly that it failed to achieve the required feeling of peril, and once we started applying stronger forces onto it, it would explode and completely lose it’s form. Luckily, There is lots of great NASA reference of smaller volumes of water and it’s behaviour in space, relative to the surface tension and friction at this scale, so we looked towards that to achieve something that was much easier to art-direct.

We shot performance elements of Jen submerged in the pool against green, and later again in a 14′ tank built of optical glass for close-ups. However, other than that the sequence was entirely CG, so we had full control over camera blocking. This really allowed us to craft the sequence on editorial, initially with Previs, and then refining it in post with our animators, including the basic animation of water volumes, which our FX simulations would later use as general reference targets.

The unexpected aspect of these effects was that as soon as we layered up too much complexity into the water simulations and shading, it would distract from Jen’s powerful performance, which was the core of this scene. So we began a process of both simplifying the overall form of the hero water volume, as well as reducing the level of refraction and distortion of the water which we view Aurora through, in order to preserve focus on her struggle. To make up for this, we would then layer as much droplets, spray and familiar water structures as possible around the periphery of her without distracting from her performance.

The movie is full of motion graphics and holograms. Can you explain in detail about their design and creation?

There were several holograms required throughout the film, many of which played a very specific narrative role. One of the most involved holograms was the Dance Machine video game, which had holographic CG dancers act out dance sequences for Jim and Aurora to mimic. For the dancers, Morten wanted them to look like futuristic technology, but still read as ‘gamey’. We looked at a lot of reference of current high-end video game cinematics, and used these for design inspiration. We motion captured professional dancers portraying the moves, applied them to the characters, then rendered them with a lot of supporting technical passes to create the holographic look in comp.

The holographic attendant who wakes Jim and Aurora from stasis was also a major holographic character for us. Morten wanted her to appear soft and inviting, but clearly projected from futuristic technology. Erik had the idea to have her face properly represented when viewed from Jim’s POV, but then deteriorate when viewed from the sides, including seeing the backside of her face when viewed from behind, like the inside of a mask. To achieve this, we created a CG model of her bust, based on photogrammetry model from Captured Dimensions, then projected plates of the actress’ performance onto the geometry, which we captured using a three-camera array set up. It worked great, and gave us a robust three dimensional hologram that we could track along with Jim’s moving pod and render trough various camera angles.

Is there any invisible or unusual effect you want to reveal to us?

One aspect of the work that I’m very proud of is the amount of VFX that actually remains invisible. A good sign that we did our job well! This involved a lot of set extension, stunt work, split comps, and work of this nature. Over 80% of this film was touched by VFX.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

The Avalon and the look of space probably gave me the most anxiety over the last year and a half. We had so many massive CG exterior shots, including and especially the climax of the film, that if we didn’t pull this off, it would have absolutely compromised the credibility of the entire film. No pressure, right?

What do you keep from this experience?

This was the most inspiring team I’ve ever worked with on a film; there was so much talent and skill both in the VFX team and throughout the rest of the film crew, and their dedication and professionalism was something that made me proud to be part of this film.

How long have you worked on this show?

I joined the film during pre-production in July 2015, and delivered the final shots in November 2016

What’s the VFX shots count?

Around 1400 total, with 1150 at MPC.

What was the size of your team?

Over six hundred artists and production staff were involved in MPC VFX alone on PASSENGERS, as well as support staff and additional crew involved in MPC Previs, Postvis, Motion Graphics.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– MPC: Dedicated page about PASSENGERS on MPC website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2016