In 2017, Christian Irles explained the work of Cinesite on ASSASSIN’S CREED. He then works on AMERICAN GODS and MARY POPPINS RETURNS. He joined Image Engine in 2018.

How did you and Image Engine get involved on this show?

Client-side VFX Supervisor Robert Nederhorst was really impressed with Image Engine’s work on LOGAN and wanted to work with us. He and VFX Producer Kerry Joseph reached out to us about the project.

How was the collaboration with director Chad Stahelski and VFX Supervisor Robert Nederhorst?

Throughout the project we had a good, honest collaboration with both Chad and Rob. We spoke multiple times a week. They knew that due to the duration and complexity of the shots, it was going to be a long ride involving lots of patience and trust! Chad is not the biggest fan of CG, even less so if it involves digital stunt work due to his extensive experience in stunt coordination and supervision. It took time to make him feel comfortable but once he saw the potential, we think he fully embraced it.

The longest shot we had was 1000 frames requiring copious amounts of CG, complex plate stitching and hours of comp integration. It’s difficult to visualize a shot like that until everything comes together. It’s a bit of a catch 22, really. We work in an industry in which our clients need to see visual results to feel confident, but we can’t show polished visual results without having taken all the other steps beforehand. Trust is definitely a very important ingredient in what we do.

What was their approaches and expectations about the visual effects?

Their expectation was for our sequence to look photographically real and action-packed. In terms of approach, we were asked to work within the visual boundaries of what had been filmed, while being encouraged to improve the action beats, whenever possible.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

We approached the sequence in a pretty standard manner in terms of planning: Build our assets while plates are match-moved & bikes roto-animated, followed by Layout (plate stitch), Animation, FX, Lighting and Comp approval stages.

What are the sequences made by Image Engine?

We worked exclusively on the Bike Chase sequence.

How did you approach a crazy action sequence like the bike chase?

We approached it with the same excitement as going to watch a John Wick film! The team and I were delighted to have the opportunity to work on this franchise, and also thrilled by the sequence itself and the challenges it presented to us.

Work wise, we took a pragmatic approach. Everything we had to achieve in terms of visual effects work had to be anchored in reality. As we know by the style of the first two John Wick films, there are no magical or fantastical elements. The films are pure raw action, based in a very believable world. Our work had to seamlessly blend with the photography Chad and Rob had filmed.

When planning the execution of our shots we broke it down as follows:

- Create photoreal assets that match practical ones (i.e bridge and bikes/riders)

- Create invisible camera transitions between Verrazano bridge plates and greenscreen stage plates

- Match our animation style to the stunt action shot on the bridge

- Sprinkle believable looking FX elements (again, referencing practical bike stunt work)

- And execute flawless 2D integration

Each one of these steps offered their own unique challenges, as you’ll read below.

Where and how was this sequence filmed?

The sequence was filmed in two separate locations: Verrazano Bridge in New York City, and a green screen stage aptly called ‘The Greenscreen Bike Room’.

At the Verrazano Bridge, professional stunt drivers did all the bike chasing action, riding at 100km/h. In the same location, crash stunts were performed using rigged bikes and dummies (safety first!).

All the close-up fight action involving Keanu was filmed in the Greenscreen Bike Room. He and the assassins sat on motorcycles moved around by film crew dressed in green from head to toe. A lot of attention was paid to the action choreography, the camera moves (to be able to stitch these with the Verrazano bridge plates), and the interactive lighting to make sure it felt like they were riding on the bridge at 100km/h as well.

Can you explain in detail about the creation of the CG bikes and riders?

The CG bike model was provided to us by production. Although textures were provided as well, we decided to re-texture it knowing how close it would get to the camera and the damage it’d have to endure.

Riders were modeled and textured based on cyberscan and texture photography provided by production. Close attention was paid to having accurate cloth simulation once in shot context. Our model also had to allow for one of its arms to be severed, to his disappointment.

Can you tell us more about the shaders and textures work?

Texture work on John Wick was achieved in Mari and Substance using a combination of procedural maps and texture photography provided by our clients. Shading of all assets was done in our open-source software, Gaffer. We use Arnold as our renderer.

Can you elaborate about the animation of the riders and bikes?

We animated our bikes and riders taking cue from the stuntmen in the Verrazano Bridge. The goal always was to not be able to tell the difference between the two (practical vs CG). This being said, Chad and Rob sometimes asked us to go a little over the top to give the action more punch!

How did you work with the SFX and stunts teams?

Unfortunately we didn’t get a chance to collaborate with the SFX and stunt teams as we got involved with the project once principal photography had wrapped.

Can you explain in detail about the face replacement work for Keanu Reeves?

Depending on the action, we took two different approaches for Keanu’s face replacement.

2.5D face replacement: Production had very limited time with Keanu on the Verrazano Bridge in New York City. They were only able to shoot one take of him riding down the bridge at a constant distance from the camera. This take became the base for our 2.5D face replacements as it was filmed in the correct lighting conditions.

The methodology we followed for the 2.5D face replacements was to roto-animate both Keanu’s head from the element plate mentioned above, and the stunt man’s head in the Verrazano bridge plates. In Nuke we then projected Keanu’s face onto its corresponding geo, and snapped that geo onto the stunt man’s head geo. Once the alignment in 3D was good, we proceeded with finessing the integration.

3D face replacement: we created Keanu’s 3D face replacement using his cyberscan and texture photography. His hair was created in Houdini.

How did you handle and create the various transitions between the different plates?

We stitched the plates together in our layout department; this was truly the foundation of our shots. But in order to do so, we had to match-move every plate, and roto-animate every practical bike. We also needed rough keys for the green screen plates so we could see the CG bridge behind the actors.

Once layout had all the cameras and bikes in 3D space, they began the process of assembling the shots. They made sure the practical and CG Verrazano Bridge always lined up, that the speed between plates during the transitions was consistent, and that the camera blends were seamless.

Even though we received a rough edit to match to, we had creative freedom to make the shot work timing wise (ie making the shot shorter or longer, if required). What Rob and Chad wanted in the end was for the plate transitions to be seamless while retaining the dynamic pace of the sequence.

Can you tell us more about the FX work?

The FX work on this project included blood, tire smoke, helmet, gun, and bike debris (ie smoke, sparks, and lots of flying pieces).

Can you explain in detail about the environment creation?

At the early stages of the project (when we were brainstorming on how to build our bridge) we knew we had to nail two things: 1- our bridge had to look identical to the practical one as we would be transitioning to and from it, and 2- it had to be longer than the real bridge due to the duration of some of our shots.

We modeled the bridge using the lidar provided by our client making sure we could duplicate and repeat it as many times as needed. Fun fact: in the longest of our shots, Keanu and the assassin’s drove through a bridge 3 times the length of the real one. Movie magic!

The bridge was textured using a combination of procedural maps and texture photography from Verrazano Bridge.

Last but not least, lookdev! In order to achieve a perfect match between our bridge and the real one, we camera tracked a Verrazano bridge plate and rendered our bridge using that camera. That way we could A/B between the real bridge and the CG bridge, and fine-tune any model / texture / shading / lighting discrepancies.

The distant city outside the bridge was achieved in DMP using tiles provided by production.

How did you handle the lighting challenges?

The two main challenges we encountered from a lighting perspective were location based.

Our CG bridge (and other assets) had to look identical to the Verrazano plates. We tweaked our model, textures, lookdev and lighting while A/B-ing between CG and plate until we couldn’t tell them apart. CG bike extensions in the greenscreen room had to match the interactive lighting used on set.

Which sequence or shot was the most complicated to create and why?

Although most of our shots followed the same methodology, the hardest one was definitely the longest in duration. It included one plate from Verrazano Bridge, and two from the greenscreen stage. We seamlessly stitched these 3 together to make one continuous shot. To it, we added our CG bridge, multiple bike/riders, swords, gun shots, blood, a rider getting his arm severed and plenty of FX goodness. Comp wise, we found that tackling the shot in small sections was the most successful.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

2D Comp integration. It was single handedly the most challenging part of these shots. We knew we would get there, but it felt like chipping away at it with the tiniest chisel. Let’s be honest, greenscreens are always hard. However, these were exponentially harder due to their length, constant lighting changes (ie practical bike lens flares and dynamic bridge lights), complex clean ups, and how we had to stitch these – in an invisible manner – with the Verrazano bridge plates.

Black levels, lens flare contamination, focus, edges, motion blur. All of these had to be perfect on every frame otherwise the shots didn’t look right. As we approached the closing stages of the show, we would overexpose the Comps in RV by 2 to 3 stops, crank up the saturation by 50% and literally go frame by frame to flag any foreground/background mismatches.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

I have a soft spot for two shots:

The first was our longest and most difficult shot; it had it all: invisible transitions between Verrazano bridge plates and greenscreen stage, CG bridge, bikes and riders, a big CG bike crash, CG swords and blood, gun shots, a severed arm and plenty of Keanu’s glorious action moves. Pure John Wick essence.

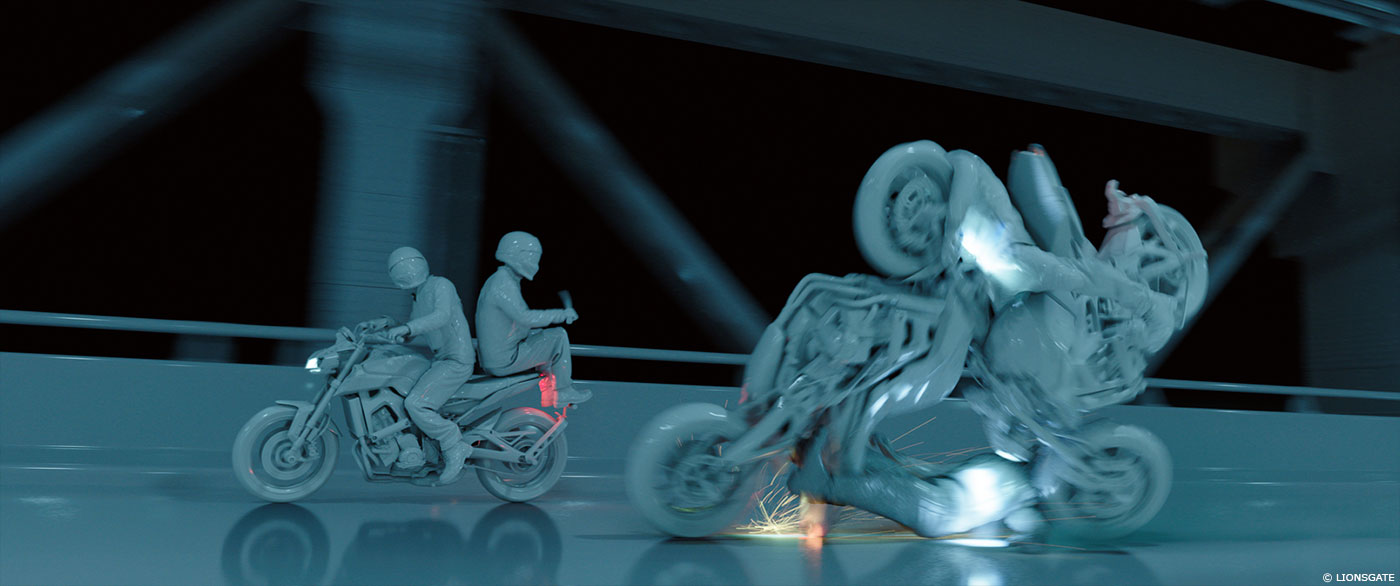

The other is the fifth shot in the sequence in which one bike flips up in the air and takes out another. The shot is fully CG. I am personally very proud of it, kudos to our fantastic team!

What is your best memory on this show?

Rob telling us in a cineSync that Chad thought our fully CG shot was plate photography. When working on photoreal projects, this is the highest compliment you can wish for.

How long have you worked on this show?

We began work in September, 2018.

What’s the VFX shots count?

Believe it or not it was only 8 shots. However, due to their duration and complexity it felt more like a 100+ shot show! We delivered a total of 1918 frames (1 minute and 20 seconds, approximately).

What was the size of your team?

79 amazing artists and production staff!

What is your next project?

Disney’s MULAN.

A big thanks for your time.

JOHN WICK: CHAPTER 3 – PARABELLUM – Bike Chase Breakdown – Image Engine

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Image Engine: Dedicated page about JOHN WICK: CHAPTER 3 – PARABELLUM on Image Engine website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2019