Back in 2018, Andrew Whitehurst explained the visual effects work on Annihilation. He then worked on the Devs series before joining ILM in 2020.

How did you get involved on this show?

When I was asked if I would be interested in working on the film of course I said “Yes!” immediately. I had an interview with Jim (James Mangold) where we discussed films we loved, the scope and vibe of the project, and banjos. (Jim plays the banjo), I play the guitar, but I’m “banjo curious”, so we talked about that. From there, once I was on the show it was a process of familiarising myself with the script, and the design work that had been done to date, and from there moving on to start work on helping to design the sequences and breaking down the work.

What was your feeling about being in this iconic universe?

It was an incredible honour. I have grown up with Indiana Jones, and the previous films are an indelible part of my makeup. I remember where I was when I saw all four of the previous films for the first time. I first became aware of VFX as an art form because of a 1980s BBC documentary on the making of Temple of Doom. I literally wouldn’t be doing the work I do now without Indy!

How was the collaboration with the Director James Mangold?

It was very close and very intense. Jim is always driving to make sure every shot tells the story in the best manner possible, and he was constantly pushing us. We wanted to be pushed! He was receptive to new ideas, to suggestions on improving the shots, and was always keen for us to try different approaches on a shot. There was a huge amount of very varied work on the show so our dialogue was pretty constant. I spent the whole of post production in LA in the building next to Jim’s edit suite so we could talk and review work as often as was needed, which was almost daily.

What was James’ approach regarding the visual effects?

Jim wanted to get as much as possible in-camera. The Indy films have always featured exciting locations around the world and elaborate set builds and there was no desire to do anything differently this time. With that said, Jim is no luddite, and he was keen to choose the right tool for every job, so when VFX looked to be the best approach he was fully supportive of that.

How did you organise the work with your VFX Producer?

I was incredibly lucky to work with an amazing VFX Producer in Kathy Siegel. She is also a supervisor so we could discuss technicalities of the work as well as the nuts and bolts of who should do what, and when. Kathy was also able to look after a part of the shoot when we had multiple units running and I was split across several sound stages. Kathy was incredibly supportive in making sure that I had everything I needed to get feedback to vendors as quickly as possible, and she had worked with Jim before on Ford v Ferrari so they already had an understanding, which was very helpful. There’s no way this show would have worked as it did without Kathy and her team.

How did you choose the various vendors?

We started with ILM of course, and we knew they were going to do the opening 1944 sequence and the third act of the film. Kathy and I had previously worked with most of the other vendors and so we knew their specialities. We wanted to try and hand whole specific sequences to a vendor so we didn’t have too many shots split between vendors. That meant we could target specific types of sequences to vendors because we knew they had been successful in that type of work previously, or because they had expressed a particular interest in a certain sequence. After that was the usual question of figuring out turnover timings and deadlines with each vendor.

Can you tell us how you split the work amongst the vendors?

For our principal vendors: ILM did the opening and third acts, Rising Sun Pictures (RSP) did the New York sequence, Soho VFX did the Morocco sequence, and Important Looking Pirates (ILP) did the wreck dive and water work, plus the creepy crawlies in the tomb. The Yard VFX, Firestorm, Capital T, Onyx VFX, Crafty Apes, and Midas VFX also contributed work to the show, and we had a great in-house team led by Francesco Panzieri who handled a lot of our window fill work and other one-off shots.

The opening is really intense and impressive and shows us a young Indiana Jones. What was your approach to doing that?

Going into the project the opening act was one of the first things that Jim and I talked about. I felt that trying to find a single magic bullet technique that could work for every shot was unlikely to be successful and instead we needed to plan on using multiple approaches. To that end we made sure to scan Harrison running through a full range of facial expressions, and we began the long process of building a full CG head for both contemporary and 1944-era Indy. For the shoot we used the FLUX camera rig, which adds two cameras to the main unit camera to capture more angles of the action, as well as scanning the set and capturing lighting data for every set up we shot. With all this acquired data we felt it gave us the best foundation to do the best work possible. It was key that we had Harrison to drive the performance. There is so much character in Indy and only Harrison can deliver that. He truly is driving that performance.

Can you elaborate about the process to create this younger version?

We used ILM FaceSwap, which is a proprietary suite of tools rather than a single technology, to do the work. It can use 3D facial tracking and retargeting, keyframe animation, machine learning-driven facial solves, use of the underlying plate, or full CG where appropriate. It’s the culmination of decades of development to make this fully modular system, but the key component is the artists who use it, and providing them with a tool where they can use the most appropriate techniques for each section of each shot to translate Harrison’s performance to his younger self. It would have been much easier if we had been able to define a single recipe of techniques that would work for every shot but we quickly found, as I think we all expected, that each shot had its own unique challenges so, for example, one shot would require more full CG and another could use retargeted geometry with some machine learning based solves for example. Part of the skill of the artists is in figuring out how to combine the tools to create the right recipe for each shot.

What was the main challenge about these effects?

A character performance is a combination of many contributing factors, movement, surface properties, texture, lighting, etc. Each of these needs to be just so for the shot to work, and when we felt a shot wasn’t quite right, it could often be hard to exactly pinpoint what we needed to adjust to get the desired result. We were able to compare our shots with previous versions of the shots to see if we had strayed from the path somewhere, we could also look at other similar shots that we felt were working better, and of course we had the whole Lucasfilm library of earlier movies to look at for reference. By looking at all these points of comparison we could iterate our way towards getting every shot to work.

Like every Indiana Jones picture, you are traveling around the globe a lot. Can you elaborate about the environment work?

There is a huge amount of environment work in the film, but all of it that can be is derived from practical locations. Our overall approach was to scout potential locations then LiDAR and photograph them. Many of these locations were places we were actually filming in, like Sicily or Morocco, but there were some places that we shot VFX plates and scanned alone, such as the Austrian Alps for the opening sequence. As the film is set in the past we also, in collaboration with the art department, did a lot of research through the archives to get as much reference imagery of the locations in 1969 as possible. From this reference we were able to present Jim with a range of options on buildings, textures, signage and so forth that we could then work into the asset builds.

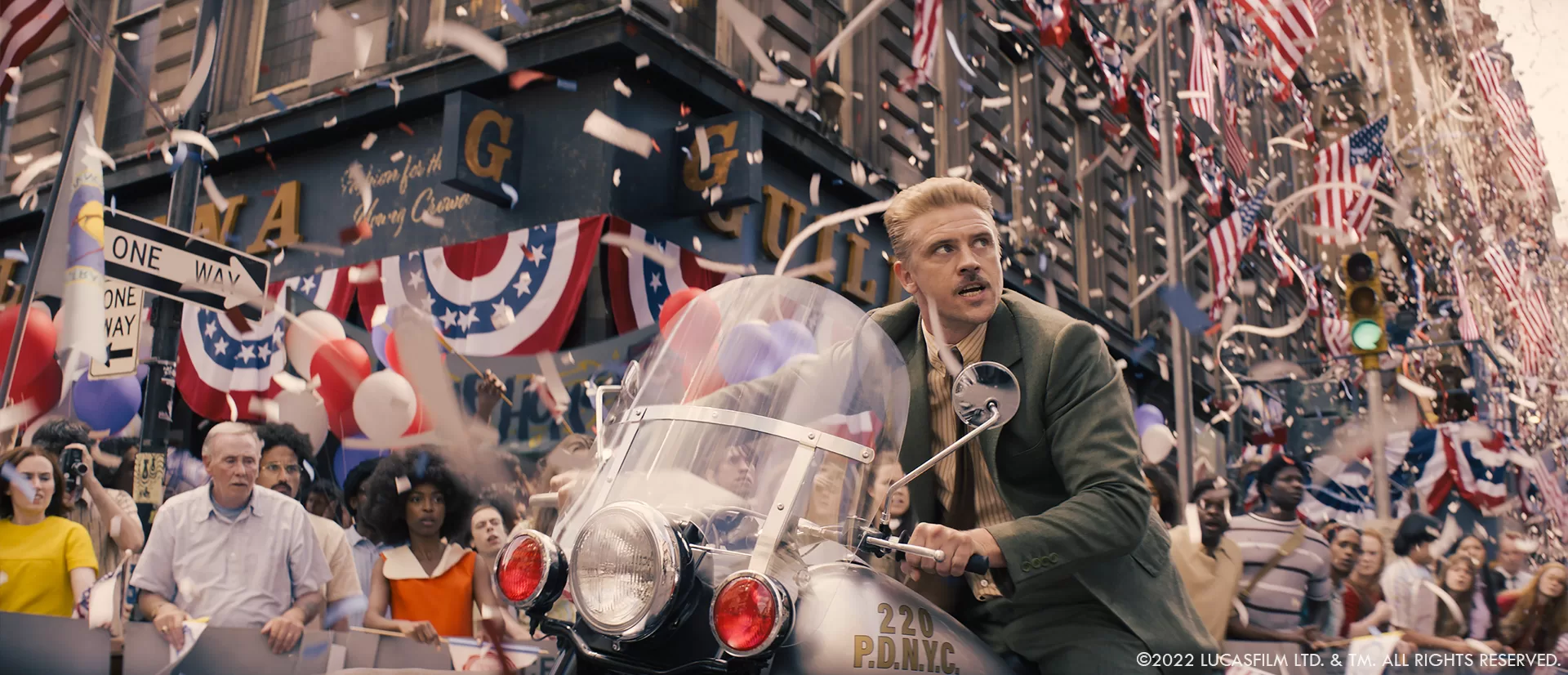

Can you tell us more about the New York Parade recreation?

The majority of the street level shots were filmed in Glasgow, Scotland. The art department did an amazing job dressing buildings at street level and we had as many extras as Covid limitations would allow. The vehicles and buildings were scanned to help build out the city into the distance (Glasgow is a lot smaller than NYC), and to add the necessary extra stories to the buildings to get the right height for the film. We decided early on that trying to do the falling ticker tape in camera would lead to very slow reset times on set, and would likely lead to myriad continuity issues, so we limited ourselves to scattering some fallen tape on the streets on location and that everything in the air would be added in post. We used a vehicle with an eight camera array on it to run down the route so we had material we could use for any later process close ups of our principals that we needed to shoot back at Pinewood. RSP did amazing work on this sequence, it’s really seamless and beautiful to look at.

The film is full of stunts. How did you create the digital doubles for Indiana Jones?

We scanned every actor that we knew we would need to create a digi-double for. We scanned them in every costume that was going to be needed too. We then built the assets in a way that would enable them to be shared amongst the vendors. In the majority of cases we were only doing face replacements on stunt performers (for the more extreme tuk-tuk moments for example) so the physicality of the movement is usually a physical stunt by Ben Cooke’s amazing team. We had a handful of shots that did require full body digi-doubles, often taking over from a stunt. For example there is a shot in the third act where one of the Nazi soldiers falls from the bomb bay of the Heinkel. Stunt performer Tom Cotton dropped from the elevated plane interior set at Pinewood onto a mat. We body tracked his performance and transitioned to a digital double that was then yanked backward by the simulated air drag, as well as continuing to fall away from camera, which is something that it would not have been possible to achieve practically.

Which stunt was the most complicated to enhance?

We had a shot when Helena is chasing the Heinkel on a motorbike where she grabs onto the Heinkel landing gear and dumps the bike. This stunt was filmed on a real grass runway at speed with full size plane landing gear rigged by SFX to the side of a truck. A stunt performer did the grab and we then had to add the CG Heinkel, all the rain, and much of the environment as the truck obscured a lot of the practical background in the frame. That was a lot of work.

How did you film the tuk-tuk sequence?

The tuk-tuk chase was filmed mostly on the streets of Fes in Morocco, with some practical set builds for certain sections at Pinewood, and some bluescreen process work for close ups. The sequence was pre-planned extensively with storyboards and pre-vis after second unit director, Dan Bradley came up with action beats that would be possible to stage on location. In a similar manner to the NYC sequence, we used an eight camera array vehicle to run the entire route as we knew that we would be filming the close ups against a blue screen at Pinewood. When shooting the bluescreen material we were careful to respect how you would mount a camera if you were trying to shoot this material for real, so we simulated hard mounted cameras, or cameras on a chase vehicle. The goal was to always have a practically plausible shot. Soho then took all the material and built 3D sections of the city, or used the array footage, to create backgrounds for the bluescreen shots. We also had to clean out a lot of anachronistic material from the location footage, like mobile phone masts, satellite dishes, and so on. It was a huge undertaking but I think the whole sequence looks earthy and real, and that’s testament to Soho’s work on it.

Can you elaborate about the design and creation of the Fissure in Time?

The Fissure in Time was a classic Indiana Jones moment: something supernatural, but that still feels like it is derived from nature. We looked at a lot of footage of real storms to see what inspiration we could draw from them. We also looked at cloud tank footage as that had some of the natural, but weird, look that we were striving for. Jim had asked that as we got closer to the fissure itself that the clouds in the storm should become stretched and pulled through the fissure so it looked like a cloud waterfall. ILM took all of these references, and some concept art that we generated, and built a collection of cloud shapes and animations that could be assembled to create the desired final result. It was extremely difficult work as it needed to feel magical but also grounded in a threatening reality. The way that we approached the fissure was planned using previs and storyboards so that when we shot the plane interiors on the stage at Pinewood we knew how violently the plane had to shake, what the lighting levels on it should be and so on.

Can you explain in detail about the creation of the Siege of Syracuse?

We knew from early days in pre-production that Ancient Syracuse would be our biggest CG build for the show. Whilst we were able to use locations in Sicily for castle interiors and some shoreline, the majority of the city and its surrounding countryside would have to be created in post. We prevised and boarded the sequence so we knew in what order the action would take place. That then drove the coastline we designed. For example we knew that the Heinkel would have to fly over water so it could take fire from Roman triremes whilst simultaneously Indy looked out of a side window and saw Achimedes’ siege engines at work. That meant the plane had to be flying into a substantial harbour bay area to allow for both these events to happen at the same time. By working through the previs, and the evolving edit, we could adapt our shoreline, and city layout to fit the action. The city itself was based on research we and the art department had done into ancient Greek architecture and town planning. We were historically accurate where we could be, i.e. the styles of housing, polychrome colour on the temples etc,, but the narrative requirements had to take precedence so the layout of the land is not a perfect match for the ancient city. The city was built to a remarkable level of detail. You could fly over any of the streets and they were fully detailed and populated with CG crowds.

How did you animate the planes and the Roman boats as well as the ocean?

The planes were keyframe animated, but also featured a lot of secondary animation like flex in the wings and the movements of the control surfaces. The ocean surface was a simulation with bespoke sims for projectiles crashing into the surface and for boat interactions. We filmed some waves crashing against the shore in Sicily which we were able to use on our CG shorelines.

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

Every sequence had its challenges, and it’s the nature of a film like this where we follow our heroes on a journey across the globe that almost every scene is somewhere new. That said, I think that the opening sequence was probably the toughest to do because most of the environment was digitally created, and on top of that the creation of the 1944 Indy performance was something new and we had to figure out how to do it, before we could actually start to execute it.

Is there something specific that gave you some really sleepless nights?

Mostly the 1944 Indy shots because whether the shot is working or not depends on the smallest of details, often barely tangible things. I spent a lot of time drawing or painting Indy to force myself to really examine his face in detail with the thought that it would help me when reviewing the shots. The more you really study something, the deeper your understanding of it becomes. Young Indy haunted me for quite a while.

What is your favourite shot or sequence?

That is like asking someone who is their favourite child! There is one small section that always gives me a particular thrill though, and that is the sequence where Helena chases the Heinkel down the runway and scrambles aboard. It was really fun designing the sequence with previs, then shooting it on a stage with Phoebe getting blasted with wind and rain giving it her all, to seeing the beautiful animation on the lumbering bomber as it lurches down the runway just missing Helena. All the pieces just came together really well here and it’s still so exciting every time I see it, and I’ve seen it a great many times by this point!

What is your best memory on this show?

I will never forget seeing Harrison Ford in the costume for the first time.

How long did you work on the movie?

I was on the film for a little over three years.

What’s the VFX shot count?

Around 2350 shots.

A big thanks for your time.

// Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny – VFX Breakdown – ILM

// Trailers

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

ILM: Dedicated page about Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny on ILM website.

Rising Sun Pictures: Dedicated page about Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny on Rising Sun Pictures website.

The Yard VFX: Dedicated page about Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny on The Yard VFX website.

Midas VFX: Dedicated page about Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny on Midas VFX website.

Disney+: You can now watch Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny on Disney+.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2024