Kevin Baillie began working in the visual effects as previz artist on STAR WARS EPISODE 1. He joined The Orphanage in 2000 and have worked on numerous films such as HELLBOY, THE DAY AFTER TOMORROW or SIN CITY. He then worked at ImageMovers Digital on projects like A CHRISTMAS CAROL or March NEEDS MOMS. In 2010, he founded Atomic Fiction with Ryan Tudhope.

What is your background?

I’ve had an interest in VFX ever since I saw my very first movie in a theater: ET. The popcorn tub was as tall as I was, but I still loved the film! Movies like BACK TO THE FUTURE kept getting me more excited about fx-driven films. When JURASSIC PARK came out during my Freshman year of high school (1993) and I saw how utterly convincing the effects in it were, I realized that I wanted nothing more than to be a VFX artist!

With the help of our amazing CAD class teacher, Rick Nordby, my friend Ryan Tudhope and I began learning 3D packages, starting with 3D Studio R2 for DOS. We made animations for high school assemblies, which got us a small job, which led to a bigger job and ultimately landed us a gig at Microsoft. Because of our school-to-work arrangement with Microsoft, we were featured in a documentary funded by the George Lucas Educational Foundation. That opened the doors to a job possibility at Lucasfilm and, through a TON of hard work and a lot of luck, we landed a job on the STAR WARS EPISODE I previsualization team! Two days after graduating from high school, we started working at Skywalker Ranch directly with George Lucas and his crew. Needless to say, we were the happiest kids on earth!!

Since then, I’ve been involved with over 30 different films at several different companies and have been VFX Supervising for almost ten years, most recently with Atomic Fiction – which I own together with Ryan.

How did Atomic Fiction got involved on this show?

Many of us had worked with Robert Zemeckis at ImageMovers Digital, his joint venture with Disney, on A CHRISTMAS CAROL. When Disney decided to shut the doors at IMD, the idea for Atomic Fiction was born. We had ideas for how to do things much more efficiently, while retaining a top-tier quality level. We flew to Carpinteria, which is where Zemeckis has his offices, and pitched our ideas to him and his producer Steve Starkey. I guess they liked what they heard because, when the opportunity to film FLIGHT arose, they immediately came to us for their VFX needs! We couldn’t be more honored.

What was your feeling to work again with director Robert Zemeckis?

Amazing! Zemeckis is responsible for one of the films that made me fall in love with effects and movies: BACK TO THE FUTURE. How cool is it to get to work so closely with someone you’ve looked up to since you were 7 years old?!?!

How was you collaboration with him?

You’ll hear a lot of people who have worked with Zemeckis for decades say things like « Bob is the smartest guy I know. » And you know what? They’re right! He has such a clear vision, is incredibly reasonable and trusts in his crew to not only execute on his vision, but also to bring their own ideas to the table. He pushes the whole team to make a product that’s better than they ever believed they could. I’m very proud of the effects that we created together, but even more proud of how much fun we had going through that process! I’m a firm believer that if the work isn’t fun, you’re doing something wrong (laughs).

What was his approach about the visual effects?

One of the amazing things about Zemeckis is his versatility as a filmmaker. Just compare USED CARS vs BACK TO THE FUTURE vs FOREST GUMP vs CONTACT vs A CHRISTMAS CAROL and I’m sure you’ll agree. With every one of those projects, the role of VFX is different. Whereas in CONTACT they played a bigger role, their job in FOREST GUMP was to be invisible. For FLIGHT, Zemeckis wanted the VFX to mirror the mood of the story: realistic & gritty. Our job as the VFX team was to create effects that support the story, not to call attention to themselves. Even in the plane crash, you’ll notice that there are no big fireballs or lens flares – it all looks like it could’ve been filmed during a real event, by a real camera.

With the help of the amazing SFX Supervisor, Michael Lantieri, we actually did film a lot of the action for real! The interior shots of the plane turning upside down, for example, were filmed on a large rotating rig that actually turned the cabin crew and Denzel upside down. Having such realistic footage to start from made the task of creating convincing VFX much more successful at the end of the day.

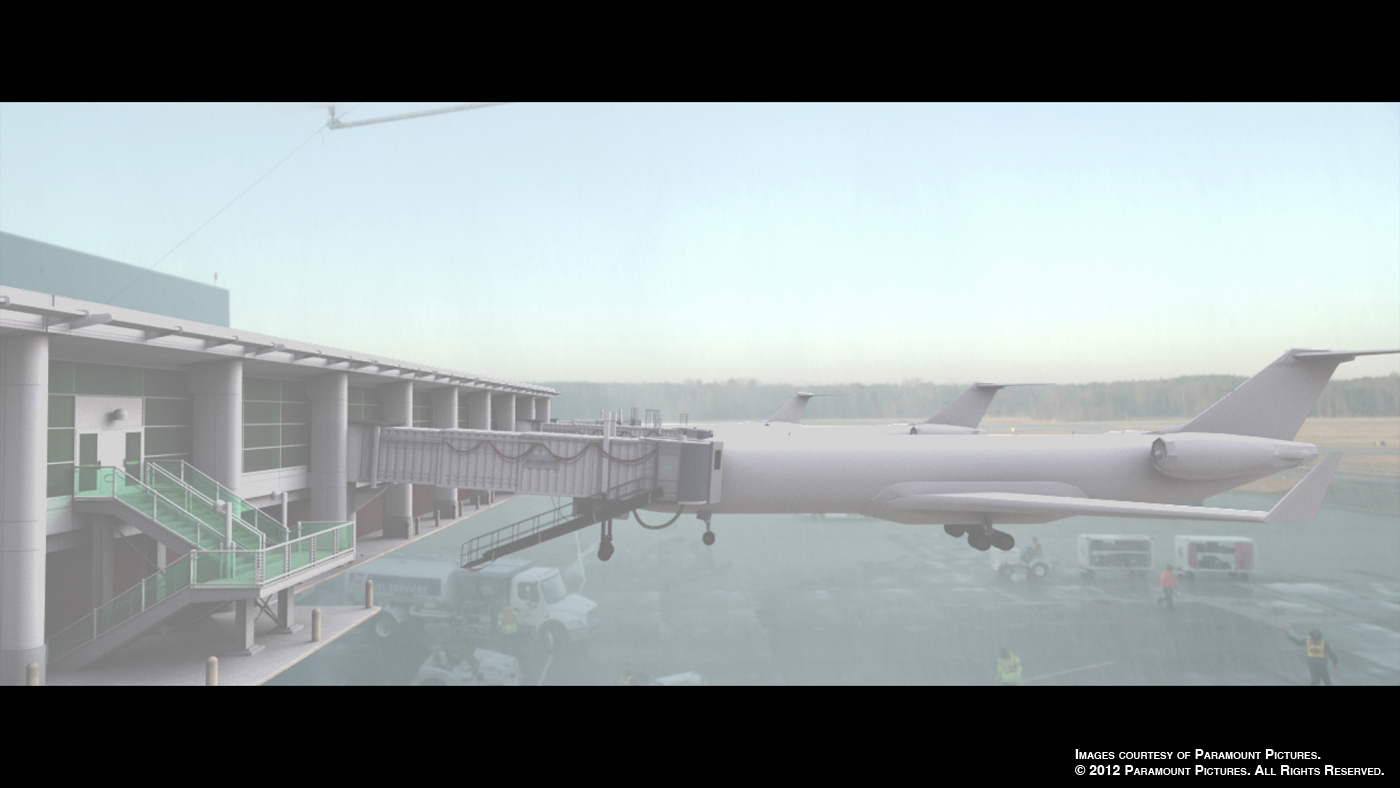

Can you tell us more about your work on the wide shots of the airport?

After 9/11 security at airports is, as we all know, much tighter than it was in the « old days. » You can’t drive a camera crew out to any airport and shoot a bunch of footage anymore. We were also on a tight shooting schedule so, even when we were able to film near an airport, often the weather was the exact opposite of what we wanted it to be! Because of that, extensive VFX were required to do any scene that took place at an airport. Some of the shots were enhanced using set extensions and some of them were completely CG.

Can you explain to us more about the airport creation for the wide shot under the rain?

That shot, in which Denzel’s character Whip is doing his pre-flight check, was particularly difficult. It was supposed to look like a stormy day at Orlando International Airport, but we had to film the plate for it on a blue-sky day at a small private airport in Georgia. Not exactly ideal conditions!

Our Production Designer Nelson Coates and SFX Supervisor Michael Lantieri were able to dress in the foreground with a real MD-88 airplane, some airport tugs and baggage carts, and an area of artificial rain that covered the foreground pieces. Everything beyond that – airport terminals, airplanes, the control tower and thundering skies – had to be created entirely digitally! The fine folks at Orlando International airport allowed me to take extensive reference photography of the airport’s terminals and runways, which our talented team of artists used to faithfully recreate the airport.

Brian Freisinger modeled the airport, Mieke Hutchins matte painted it, Mike Janov simulated the rain and Youjin Choung pulled all of the elements together in the composite. As is always the case, an amazing team is the most important thing with creating a shot like this, especially if it’s one that nobody is supposed to know is an effect at al!

How did you create the plane?

The plane was initially designed as a combination between several commercial airplanes. Through the shoot of the film, that design changed a bit, and we took that final design and built it off of extensive reference photography and blueprints. Interestingly enough, the artist who designed the original plane, Colie Wertz, was also the one to build the final CG model of the aircraft! That continuity, and a lot of attention to detail, helped to make it believable. We used May to model it, Mari for texture paint, V-Ray and Maya for lookdev and lighting, and Nuke for our final composites.

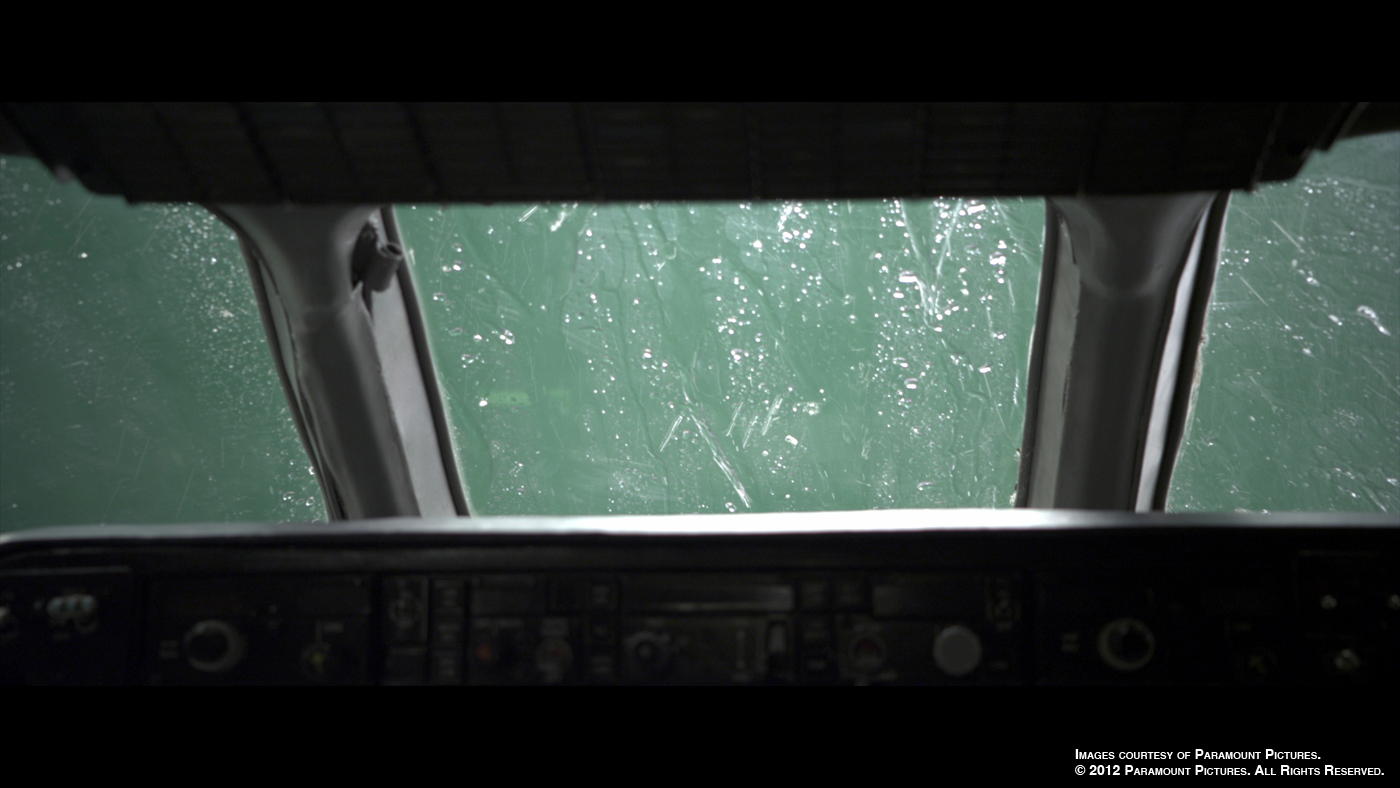

What was your approach for the creation of the various environment seen through the cockpit?

Many of the environments you see out of the cockpit are enhanced live action plates, which we filmed from a helicopter. FLIGHT’s Director of Photography, Don Burgess and I talked at length about how to capture the maximum amount of footage in the least amount of time. We only had access to the helicopter on the first day of production, so we didn’t even know what angles we needed to shoot for! Don came up with the idea for an awesome rig that utilized 3 RED Epic cameras w/ 14mm lenses on a single nose-mounted plate. By carefully orienting the cameras, we were able to record almost 240 degree, stitchable, moving panorama of everything the helicopter saw! This gave us maximum flexibility in post-prodcution. We then enhanced those plates by stabilizing and speeding up the footage, adding clouds for a sense of 400mph speed (the helicopter topped out at 70mph), and replacing skies to give the perfect mood and energy level.

For things we couldn’t film, we used many sources of inspiration for creating fully-digital environments. Our matte painting crew, lead by FLIGHT’s Digital Art Director Chris Stoski, were able to create synthetic environments that cut seamlessly with the real thing. That’s no small feat!

Have you created some previz for the flight sequence?

The talented team at The Third Floor created a previs sequence for the crash scene, which was very helpful to the entire production team.

How did you manage the clouds for the big storm?

We used a combination of Maya Fluids clouds and matte painted clouds on cards throughout the flying sequences. Since render times can get pretty intense when rendering volumetric, we developed a library of « generic » cloud actions and angles that the compositors could use to create about 80% of the shots. When those elements didn’t work, we created custom clouds for those shots. It was a time consuming process, but the end result turned out pretty well!

Can you tell us more about the engines burning?

Commercial airliners aren’t meant to fly upside down, so bad things start happening when they do. Bob wanted to show these dramatic consequences, but still wanted to feel like it was filmed for real. We created virtual cameras that were « hard mounted » to the exterior of the plane, as if we’d used super strong version of what you might see in a car chase scene. We then used FumeFX to simulate the smoke and fire. For the shot where the CO2 puts the fire out, we added little flakes of frozen particulate and oil splatters on the lens to « dirty » up the event and add even more realism to it.

What references and indications did you received from production for the crash?

Beyond what the script said and a detailed verbal turnover from Zemeckis, we didn’t receive much reference from production. There’s some great stuff out there on youtube that helps to show different aspects of what you might see in a crash, but couldn’t use any of them as direct reference since most crashes that have been caught on video end very poorly for everyone onboard. Ultimately, we had to take lessons from many sources, add in our own artistic decisions, and come up with something that was simultaneously dramatic and believable, while also serving the story’s requirement for it being a nonlethal event.

Can you explain to us in details the creation of the crash?

Even though the crash was supposed to be shot through a cell phone, we first had to create a fully realistic looking shot which we then treated to make it look degraded and compressed. All that extra detail, even though we might have thrown a lot of it away at the end of the day, adds to the believability of the event. The plate itself was filmed by Bob’s camera operator Robert Presley, who had to imagine a plane flying overhead and crashing. We matched the CG airplane into that footage and, as we finessed its animation, we were able to alter both the airplane’s movement and the plate’s timing hand-in-hand to achieve a seamless match.

The church that the plane’s wing clips wasn’t yet completed by the time we filmed the shot, so we had to recreate it digitally, using FumeFX, Rayfire, Box #2 and 3DS Max to create the simulation. The airplane’s smoke trails and crash impact FX were simulated by Allan McKay using FumeFX and Pflow, while the airplane itself was animated in Maya by Jenn Emberly & Julie Jaros, and rendered by Jim Gibbs in V Ray for Maya. The final comp was a thousand-frame monster, handled by our comp supervisor Woei Lee within Nuke.

How did you create the final shot of the crash seen from inside with Denzel Washington?

Since the real cockpit was extremely small and hard to work inside of, combined with the fact that Bob wanted to see it start to collapse and move around Denzel as a result of the impact, we decided to shoot him on a green screen and create the entire cockpit digitally for that one shot. Using extensive reference photography, Brian Freisinger modeled, textured, and lit it to match. He broke out every light into a separate render element (AOV), so that we could control the directionality of lighting fluctuations in comp. Mike Terpstra then composited the shot in Nuke, making heavy use of its 3D tools to create various aspects of the shot. He even augmented the great « dirt wave » elements that the SFX team had filmed with 3D Nuke particles. Finally, we re-timed the shot, which was originally filmed at 96fps, to give some extra « snap » to the impact.

Can you tell us more about the Nicole’s pupil changes?

Nicole’s pupils contracting as she overdoses is a subtle but disturbing effect. After filming the shot itself Kelly Riley was kind enough to let us shine a flashlight into her eye in a dark stairwell. By removing the flashlight and waiting for a moment, and then shining it back onto her, we were able to capture the action of her pupil contracting. We then used this as reference to create the effect digitally. Nuke’s spline warping tools and Photoshop were used by Natalie Baillie (yep, that’s my wife!) to complete the final composite of the shot.

How did you create the subtile close-up transition on Denzel Washington?

This was one of the subtlest and hardest shots in the film. When Bob came up with the idea of seamlessly transitioning between two totally different times and places while the camera was moving, I had no idea for how exactly we would achieve it. We didn’t have the budget for motion control, and the locations were very different, so it was kind of a worst case scenario! Then I remembered a demo that The Foundry had given showing off their Ocula stereoscopic toolset, where they were able to « move » between the left and right eyes of a stereo pair. I thought « hey, maybe we can trick Ocula into thinking that the a-side of the transition is the left eye and the b-side is the right eye, and then slowly animate the ‘interaxial’ between them to do the transition! » We did a quick test and it worked! Youjin Choung and Mike Terpstra teamed up to do the final comp, and I couldn’t be more proud of the end result.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

I know this sounds like a generic answer, but the biggest challenge was getting the film done on time and budget! Since Atomic Fiction was relatively new at the time, we had to make sure that we made great crewing decisions and were able to grow our infrastructure to accommodate a shot count that increased from 130 to nearly 400 by the end of the production. We’re super grateful to have an amazing talent pool right here in the San Francisco Bay Area and sourced some great talent from LA and Portland, so our crew was simply amazing. Our CG Supervisor Mauricio Baiocchi and Lead Developer Alex Schworer made sure that the team of 35 people had the tools they needed to get 400 shots done in just over 4 months. Between our own internal asset manager, Fidget, and Shotgun’s awesome production tracking system, we were able to keep information in order. Cloud computing was a key component in rendering the project. For that, we worked closely with the team at ZYNC, who provided the software to push all 400 shots through Amazon’s EC2 in a way that’s never been done before on a major feature film! Thanks to all of those things – the people, the technology, the cloud – we were able to live up to Zemeckis’s high standards!

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

Haha. Yeah, the seamless transition on Denzel’s face at the end of the film caused some sleepless nights. It was one of those shots that won’t look right unless it’s perfect and, since we were using very non-orthodox methods to do the shot, it was a bit nerve-racking.

What do you keep from this experience?

I have a profound sense of pride in what the team did. There were so many challenges to overcome while simultaneously growing Atomic Fiction and completing this film, and everyone pulled together to hit a home run and create award-winning VFX. The film itself is an amazing one, which helps too – it’s not every day we VFX artists get to work on a truly impactful movie. We all know someone who’s struggling, or has struggled, with alcoholism. To think that we played a role in creating a film that could have a positive impact on someone’s life is pretty great.

How long have you worked on this film?

We started pre-production in September of 2011, wrapped shooting in December, got our first turnovers in February and were done with VFX in June. It was super quick!

How many shots have you done?

FLIGHT ended up being just shy of 400 VFX shots.

What was the size of your team?

FLIGHT’s team was 35 people, including a production staff of 3.

What is your next project?

I can’t talk about our current project quite yet. But it’s really big and cool! We’re almost finished with it, in fact, so wish us luck (laughs).

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

STAR WARS, E.T., BACK TO THE FUTURE and JURASSIC PARK. They’re not as « deep » as the films I’d put on my favorites list today (now that I have some gray hair), but they’re the ones that sucked me into the world of moviemaking!

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Atomic Fiction: Dedicated page about FLIGHT on Atomic Fiction website.

// FLIGHT – VFX BREAKDOWN – ATOMIC FICTION

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2013