Daniel Kramer began his career in visual effects there are more than 22 years. He worked at VisionArt on films like INDEPENDENCE DAY or GODZILLA. He joined Sony Pictures Imageworks in 2000 to work on SPIDER-MAN. He worked also on many projects such as THE POLAR EXPRESS, WATCHMEN or HOTEL TRANSYLVANIA.

What is your background?

I’ve been in the industry for about 22 years. I graduated from UC Berkeley in 1991 with a degree in Political Science. I talked my way into an internship at a small company called VisionArt around 1992 without any real 3D experience. Interning was one of the only ways to get access to the Silicon Graphics workstations and the software that was used at that time. There I learned Prisms, the precursor to Houdini. At VisionArt there were no specialists, each artist modeled, animated, textured, rendered, composited, etc.. it was great experience. Over the 8 years I was there we went from doing small infomercials to high profile television and feature films. I worked on DEEP SPACE NINE creating the transforming fx for the character Odo and built some of the very first CG ships ever used for STAR TREK, the Defiant and Runabout. I also worked on INDEPENDANCE DAY and GODZILLA there.

I then moved on to Sony Imageworks around 2000 to work on the first SPIDER-MAN, and have been there ever since. At Sony I started as an FX Lead and moved up through the ranks to VFX Sup.

How did you got involved on this show?

Sony asked me to fly up to Vancouver to meet Nick Davis, the production side VFX Supervisor, as we were bidding on the work. Nick talked me through the project, it was just the sort of gritty, photoreal work we had been really going after at that time. We got the award for the show a few weeks later just as principal photography started. I was actually on vacation in Hawaii with my family when I got a call that I was needed in London for the shoot. 2 days later I landed on the cold and wet Beach Set, it was a pretty harsh transition!

How was the collaboration with director Doug Liman?

Since I wasn’t the overall supervisor for the project I mostly interacted with Nick Davis. I did work with Doug on set and there were a few occasions where Doug came to Imageworks to look at work in person. Generally Doug was either in New York or London so there wasn’t a lot of direct exposure once post started.

What was his approach about the visual effects?

The goal was to look absolutely real and grounded in reality. This meant everything had to have enough wear and grit to fit with the production design and no fantastical camera moves. Doug respond better when the shots weren’t perfectly framed up, or when animation wasn’t super clean and fluid. The tone of the photography was chaotic and jarring for the battle and our cg shots, elements, and animation should mirror that tone. First and foremost Doug and Nick care about the story and Visual FX always play a supporting role.

The script was still being written and tweaked while we were shooting. As a result we had to be on our toes during production as Doug would get inspiration on the day and create new shots on the fly. It was difficult for us to keep up but in the end it was worth it.

How did you work with Production VFX Supervisor Nick Davis?

Nick was great to collaborate with and gave me and the team a lot of freedom to bring new ideas to the table. He has a lot of experience working on these big, difficult productions and is particularly good working with all the big personalities and getting consensus among the filmmakers. He sheltered us a lot from that process which really allowed us to concentrate on the work. The tricky part was during post production I was in Culver City with the crew and Nick was in London with Doug and editorial. The distance and 8 hour time difference limited our contact to just morning time for us, and evening for him. To facilitate the great distance we sent over a workstation with a calibrated monitor and Imagework’s custom viewing software called Itview. Each morning we’d remotely load up their box with new review material for a shared Itview session. Itview allows multiple sites to log into a session to view images, annotate, color correct etc.. everything is syncd across all the clients. In this way Nick was able to look at full quality images in the right color space which took some of pain out of working remotely. Nick also took several trips to LA over the course of the project which helped a great deal.

What are the sequences done by Sony Pictures Imageworks?

We were responsible for most of the effects in the first 2 acts. That included militarizing Heathrow Airport and airport extensions, the shots of Tom in the dropship on his way to battle, all the beach sequences, the trailer park, and the barn sequence.

Can you describe one of your day on-set and then during the post?

The set was at Leavesden Studios north of London. We shot in the winter and mostly outdoors on the Beach set or the Heathrow set. The Beach set was pretty challenging for everyone, it was cold and wet and quickly turned into a bog we’d have to wade through each day. Nick and I would generally split up between the two units to cover everything.

For post the day would start with an 8am call with Nick where we’d go over shots and then I’d move into endless reviews with the crew. Our team is spread out across LA and Vancouver so I don’t to do a lot of desk rounds. Generally I spend the day in the review room with a shared Itview session reviewing work as it comes in.

How did you work with The Third Floor for the previs?

The Third Floor had a small team at the production offices at Leavesden and worked very closely with Nick. They had created previs for the battle before we started. Initially our goal was to match the tone and feel of the previs but as the movie and script evolved so did the tone of the beach sequences. We ended up departing from the battle previs quite a bit in the end. For other sequences like the trailer park and some of the Heathrow shots the previs was a great guide for us.

Can you explain in details about the design and the creation of the Mimics?

The design wasn’t locked down when we joined the project. A maquette had been sculpted by the production art department and there had been some 2D work from Framestore showing lots of exploration. Initial designs were a combination of solid structures wrapped in tentacles but eventually production’s art dept landed on a creature made completely of tentacles. This unique design would allow the creature to completely change shape.. growing new limbs while retracting others. This maquette had no head at all, but later we worked with Nick and Framestore to design a head that would work with this unique body.

The creature’s tentacles were made from chains of hard crystal and glass like segments. We explored many materials, animals, and insects to come up with the material properties of those segments. We eventually landed on Obsidian as a good reference model for what the creature was made of. We also mixed in Amber for some of the softer interior body segments.

Nick described the creature as having no locked down orientation where it’s perfectly happy flipping upside down or moving backward by inverting it’s body. Doug wanted the creature to feel truly alien, like nothing in our world. He described the motion as erratic and unpredictable with the ability to move with incredible speed.

How did you created their rigging and animation?

Traditional rig approaches didn’t apply to the Mimic. We didn’t have a fixed model, character volume, or number of tentacles to work with. Hand animating hundreds of tentacles would be too unwieldy and slow for shot production. Instead we developed a procedural tentacle system to generate bundles of tentacles on the fly. Each bundle is controlled by a custom Maya plugin to handle tentacle to tentacle collisions and high level controls to add or remove tentacles, handle tentacle spacing, drape and contraction as well as the ability to introduce animated noise to create extra internal motion. There are controls to grow into foot or hand positions for more articulate posing. The animators were free to add or remove tentacles per limb or even add additional limbs if necessary making each shot and character truly unique and customizable. Our Technical Animation Supervisor Dan Sheerin designed the a plugin to build and animate the limbs.

What was the main challenge with the Mimics?

It was all fairly challenging. Challenging to arrive at the character design, to build our tentacle limb plugin, and to animate the characters with great speed without losing the sense of weight.

Can you explain to us the creation of Heathrow Airport and its environment?

A section of the airport terminal was built at Leavesden and for those shots we were responsible for extending the background to see barricks, armories, troops, vehicles and fields of dropships. We also had to show the iconic Heathrow terminal buildings extending off in the distance. Rodeo FX in Montreal helped us build many of the matte paintings at Heathrow. We would design the shots in our layout dept and get approval from Nick. Once approved Rodeo would render us a static matte painting of the buildings and ground extension and provide that back to us in layers. We’d then populate and render with troops, moving vehicles, dropships etc and handle the final composite.

For the source material we took a couple of trips to Heathrow airport to collect panoramas and textures to aid in building the paintings. It was a lot of fun collecting that material as we were out on the tarmac weaving between 747’s in a scissor lift to collect our panos.

Can you tell us more about the Dropship creation?

The Dropship was designed by the production art department. When I started on the project they already had designs and temp models to be used for Third Floor previs. So there wasn’t a design question, they had done a great job designing every detail. We needed to get very close to the exterior, interior, and build it to be compatible for destruction. As a result it was one of our heaviest models in terms of geometric complexity, texture resolution and texture layers. We spent a lot of time building each individual panel in 3D rather than using displacement mapping to give our destruction pipeline more realistic geometry to work with. I really wanted to see panels bending and sliding against each other realistically when the ship was under stress or crashing. We found quickly that it collapsed unrealistically when we did our first crashing sims.. we ended up building low res, invisible support structures within the ship to give it the right stiffness and internal support needed to look right.

How did you approach the impressive beach sequence?

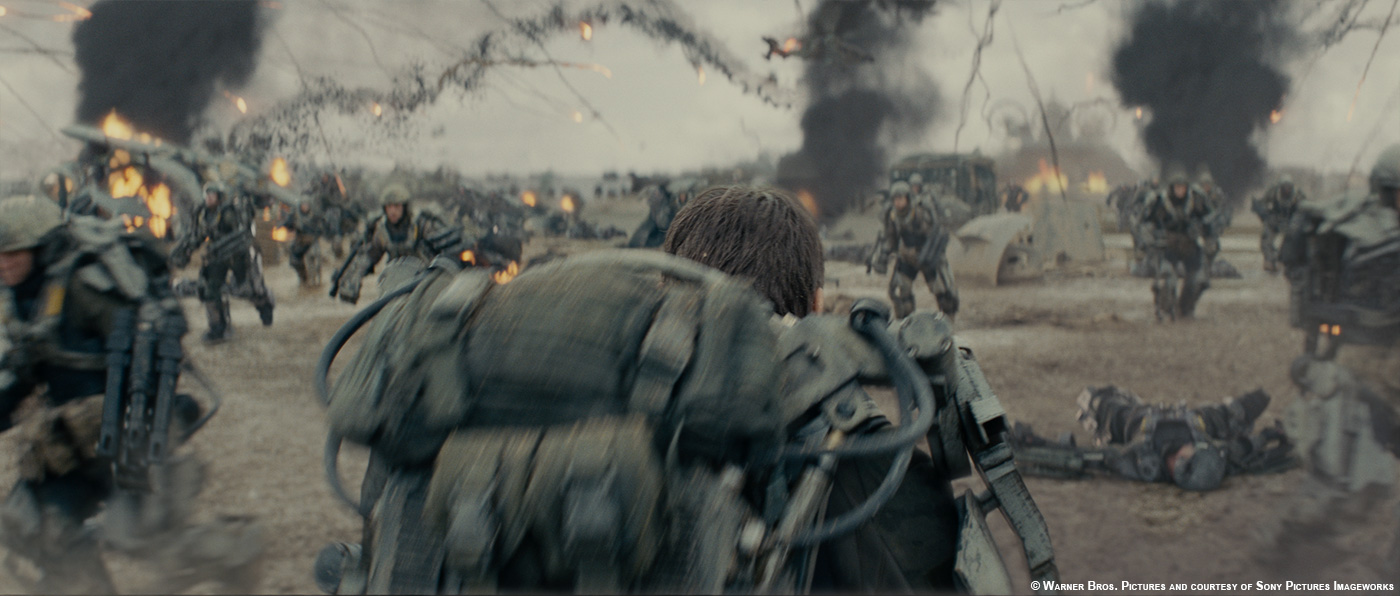

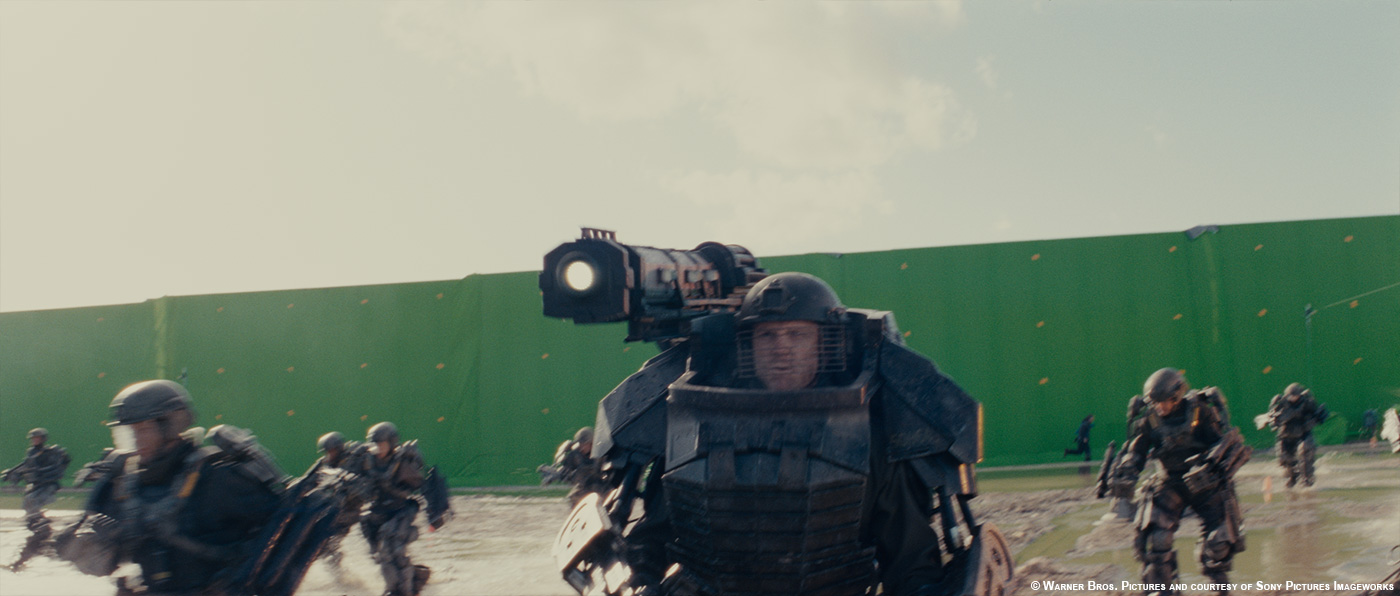

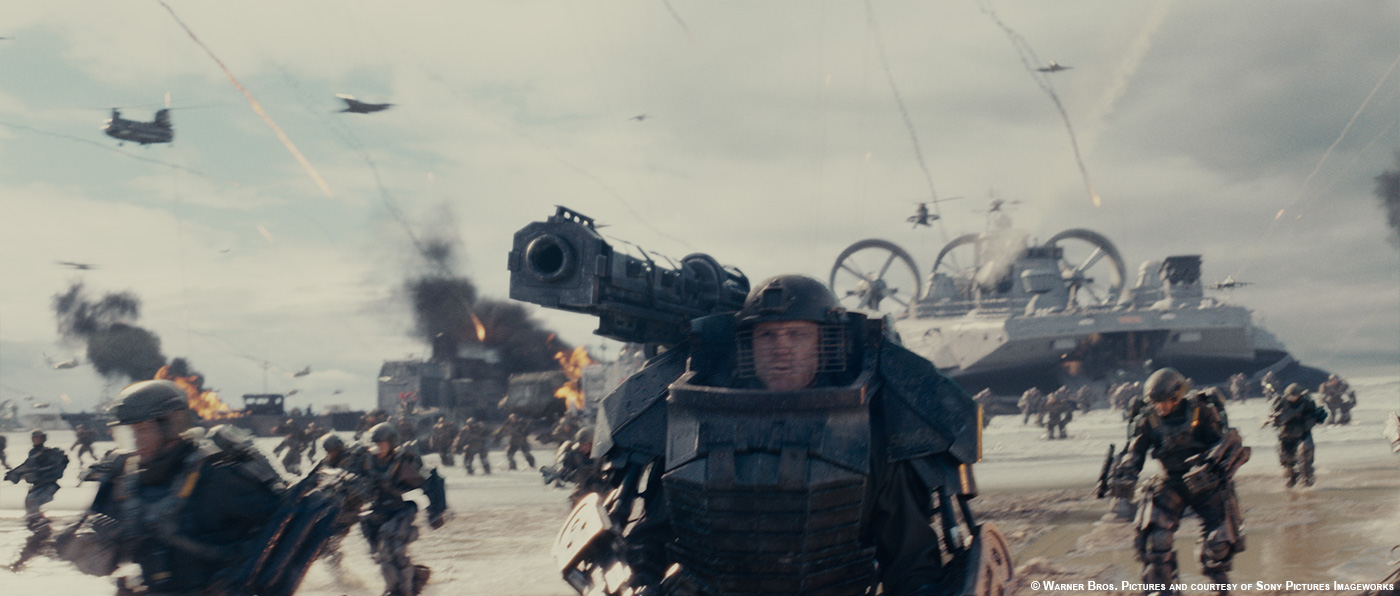

The Beach set at Leavesden was pretty extensive and surrounded by large green screens strapped to stacked shipping containers. There were quite a few exosuit soldiers on hand to fill out the area around the principle actors and the Special Effects Dept filled out the shots with gas explosions, mortar hits, and smoke columns. With all the practical effects exploding in each shot it really did feel like war shooting on that beach. Extensive practical effects really grounded all the digital work in reality and gave us great reference to match.

As big as the set was it was still tiny compared to the beach needed for the film and had no plausible beach break section for the beach landings. Even though there were practical explosions and many extras it still wasn’t nearly enough to fill out the shots. Our job was to extend the beach in all directions, add thousands of troops, ground based vehicles, all air and sea vehicles as well as add lot of extra pyro and destruction. It was a huge task.

The general design of each shot was done in our Layout department. Doug wanted the battle to feel desperate, that there was no hope of us winning this war. In every shot someone has to die, a vehicle gets hit, and he wanted to litter the beach with dead bodies. We decided to design the battle as a whole rather than thinking shot by shot. Using our Sequencer tool (which we use on our Feature Animations) we built a 1000 frame clip of war action. Layout placed animation clips for air and sea vehicles provided by the animation dept and littered the beach with dead bodies. This provided the backdrop and these assets would pass straight to lighting. Layout would also place proxies for where hero action would occur and these were handed to the Animation dept to be replaced with hero animated elements. This would include any vehicles or grunts close to camera, the mimics of course, and massive for crowds. Working as one large file we could make a change to a section of the beach and that would automatically transfer to all the other shots. We had the ability to go in and do per shot overrides as well.. but keeping it all together saved us some time. It also helped to keep continuity between the different loops. Everything had a low level of detail to keep this file lite and fast.

For the beach itself, we had a fairly detailed lidar scan of the set but that was only so useful since the beach was ever evolving. We shot on the beach for over 2 months and unfortunately sand doesn’t stay put so the lidar represented just a moment in time. The major undulations of the terrain remained static enough that we were able to use the lidar to camera track our shots.

We spent quite a bit of time texturing and shading that beach model and found that we could get a really good match at a particular scale, but if we then tried to re-use that same lookdev for a much wider or closer shot the lookdev would break down. It was difficult to come up with a unified shading model that would work for all distances. We also found that the beach varied quite a bit in color and texture from section to section. Because of these issues we took different approaches depending on the shot at hand. We came up with a set of techniques that could be used in different situations by our lighters and compers:

– For very distant beach and dunes we might be able to split in high res panoramas shot at Saunton Sands in Southern England. In some cases that worked for the ocean and beach break as well. Otherwise we’d use our cg counterparts.

– For medium distance we’d render our cg beach because it was really important that our cg troops and vehicles contact the ground properly.

– Close shots generally were in camera but there were a few occasion where we needed to have an alien emerge from the ground or terraform the ground if it was shot in the wrong location. Those might be done with a cg patch of ground or stealing ground from other plates and tracking them in Nuke.

For the water section we rendered a cg ocean and beach break simulated in Houdini and rendered in Arnold. For the closer shore line we’d also do very high water res simulations around the feet of both our cg characters and the actors in the plate to simulate wading, splashing and foam.

Everything of course came together in the Comp, this was a very comp heavy show. Because of all the practical effects it was a difficult job to layer and integrate our cg elements and sandwich them between practical events in the plate. We relied heavily on our comp artists to pull from all the resources at their disposal to design cool shots. In addition to the specifically rendered assets for a shot (vehicles, troops, mimics) the compositors drew from libraries of practical and fx generated smoke plumes, explosions, flying dirt, javelins, exploding vehicles etc. They were given a lot of freedom to layout their shots given some example surrounding shots. There were plenty of hero fx to go around but using the element library simply made the task doable without completely overwhelming our fx artists.

Can you explain in details about the creation of the beautiful first fall on battlefield of Tom Cruise?

The shot is almost entirely digital with the exception of the first few frames before the drop and the landing at the end. Nick pre-visualized the major elements of the shot with the small Third Floor unit in London to work more interactively. Once that was bought off it was sent over to us as a guide. This was one of the few really big shots that came together relatively smoothly, making steady progress over the course of the project.

For the environment we used aerial photography Nick shot at Saunton Sands as a basis for the beach, dunes and surrounding landscape matte painting. We augmented with renders of our CG beach to add trenches and scorched earth marks on the beach. The ocean was replaced and simulated in Houdini, rendered with Arnold, and we used the photography to split in the beachbreak section of the shoreline. The sky was painted from HDRI sources we had from that area.

Layout replicated the Third Floor previs and added the surrounding air and sea assets to fill it out. We used massive for the grunts and vehicles on the beach. Animation handled all the hero characters dangling from wires including our digital Cage and a few of the hero elements which passed close to camera.

FX handled the destruction of the dropship when Cage looks up with a heavy DMM sim for the hard surfaces and lots of smoke and pyro to support it. They also added raining debris and a few other hero sims including a subtle areal smoke to whip past camera to give us a sense of speed and direction.

Lighting placed smoke plumes on the landscape and aerial smoke from some of the pre-baked fx assets we created over the course of the show and added the hundreds of javelins in the sky using our pre-baked javelin field.

The beach battle have a large amount of destructions. Can you tell us more about it?

We built a comprehensive destruction library to be used on all the battle shots. The library contained both 2D and 3D assets which could be pulled in by Layout, Lighting, or Compositing. Early in the project the FX dept, headed up by Steve Avoujageli and Dave Davies, simulated diesel smoke fires, gas explosions, javelin volleys, mortar hits, splashes etc. to be used as elements for the shots. These small simulation clips were pulled in by the lighters and they rendered several generic 2D elements from different camera views and stored as generic elements for the compers. We also had a huge practical element library of real explosions, dust hits, and splashes from Nick Davis. The scenes were so chaotic that we could be pretty loose with continuity and that gave each lighter and compositor a lot of freedom to place these elements into their scenes.

We also enhanced our destructions tools for this project and integrated DMM (Digital Molecular Matter) into Houdini to work alongside our other destruction tools. DMM works by dicing up an object into small tetrahedrons which can be assigned material properties. So you can tag some tets as “glass” which tells them to break apart in a very brittle way.. or you can tell the tets they are a soft metal so they tend to stick together and bend before tearing apart.

Using this system we’d rig up a vehicle, like a jeep, and hit it with a javelin projectile, or set an explosive charge underneath it and get all sorts of great looks. The FX department simulated a bunch of different scenarios for us and baked them out to destruction the library. For generic background action a lighter or layout artist could drop those 3D assets into a shot and re-use the same stock simulation.

Can you tell us more about your work on the exoskeleton armor?

Production designed exosuites for all the principal actors and a great many extras. They were pretty impressive looking and quite heavy even though every effort was made to make them as light as possible. Our job was to simply match the suits with CG equivalents. We have several examples of full body scans of J Squad, Tom and Emily etc.. we also had very high res scans done with a hand scanner for individual pieces. All of that data including detailed photos for texture mapping helped us create our digital version. Production sent us pieces of the suits as well for our lookdev artists to accurately replicate the material properties.

How did you designed and created the really nice trails fired by the Mimics?

The weapons from the Mimics were simply called “Javelins”. The idea is that a mimic could expel part of a tentacle as a projectile. Nick Davis really wanted to make a big statement with the javelins since they’re our only connection to the enemy in many shots where we don’t see the Mimics. They present a constant, unrelenting danger to the troops and set a chaotic tone to the battle.. and they just look cool.

Each javelin pass consisted of a red hot tentacle segment at the leading edge, a sooty particulate trail, and smoke birthed off the particulate pass. We experimented with their path, firing them straight, allowing them to wiggle in air, etc. Eventually we tried tumbling them end over and spinning them. This created sort of a double helix history trail that looked really cool. Nick and Doug loved the look and we used the helix and some straighter paths to add variety. Everything was simulated in Houdini and rendered in our Katana/Arnold pipeline. The simulations got heavy really fast with the number of javelins we were adding so the FX team created a pre-baked volume with a few hundred animating javelins that we could use over and over. Lighters were able to pull that into Katana and translate/rotate it around to place it in the right spot for the shot. If they needed more coverage they could simply import a second instance and place it in a different spot or offset the time to grab a unique section of the animation. Most shots used the pre-baked system.

We did have a few hero hits as well that needed specific placement and timing. Those were simply handled as on-offs by the FX team.

Can you tell us more about the digi-doubles creation and animation?

We worked with Nick to setup a scanning tent on one of the stages at Leavesden Studios, production used Plowman Craven to provide the hardware and they helped us with the capturing sessions as well. Ken Hahn, our DFX sup, defined the process along with Chris Hebert and they ran the operation there on location. The scanning tent was segmented into 3 different stations:

– A station for full body texture acquisition.

– A station to capture FACS poses as high res 3D data and an array of DSLRs for textures.

– A station with a full body laser scanner.

All photos were done polarized and unpolarized to help separate specular and diffuse components. Once the scanning was done we’d video tape the actors in a range of motion test to give our rigging, animation, and cloth teams great motion reference. All materials for skin, hair, and suits were rendered in our custom build of Arnold which uses OSL for shading.

There is an impressive helicopter crash sequence in the barn. Can you tell us more about it?

The barn was built on the backlot at Leavesden with a section of the roof rigged to break away. A helicopter was built on a gimbal arm to allow it to push through the roof. The initial shot of the helicopter coming through the roof was done practically by SFX. We did paint out the rig and add some extra dust and debris but it was mostly an in-camera shot. There were a lot of amazing practical effects done on this film.

The rest of the shots were achieved with a digital helicopter. We needed to paint out the practical helicopter and replace with ours. We had our digital Emily Blunt at the helm in those shots as well. One of the shots is completely digital as we didn’t have a plate that would work. We used set photography and lidar to reconstruct a new virtual plate within Nuke. For the helicopter crash we used a DMM destruction pipeline we build into Houdini to bend and tear the body on impact.

Have you collaborated with the other VFX studios and how?

We did share our work with Framestore. We were responsible for building a few shared assets and we sent them our Digi-Doubles of Cage, Rita, J Squad, the Dropship, the exosuites and the Mimic. The most difficult asset to send was the Mimic since it’s built procedurally with a custom plugin to assemble and drive all the tentacles on the fly. We had several calls between our Mimic team and Framestore’s team to talk through how we designed the plugin and all the animation features needed. Framestore had to write a similar plugin to build and drive the Mimic for their sequences. Building that plugin is not trivial and they did an excellent job.

We also provided our digital Cage model and textures with Cinesite London for use in the sparing bay shots.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

It would probably be a shorter list if I told you the ones that didn’t keep me up. This movie was a big leap for me personally as this was my first show as VFX sup on a live action project. By nature I’m a perfectionist and fear failure, that combination doesn’t generally lead to restful nights!

What do you keep from this experience?

Surround yourself with great artists and supervisors and let them bring great work and ideas to the table. The artists and sups had a lot of freedom when designing the battle sequences and the shots were so much better for it. I learned so much from them on this film, they certainly elevated my knowledge and skill over the course of the project. There are too many artists to name here, but I would like to thank a few people. DFX Supervisor Ken Hahn, the Animation Sup Steve Nichols, VFX Producer Eric Scott, and CG Supervisors Craig Wentworth, Matt Welford and Karl Herbst.

How long have you worked on this film?

About 14 months.

How many shots have you done?

430.

What was the size of your team?

130 people including artists and production staff.

What is your next project?

I’m currently on 2 projects, HOTEL TRANSYLVANIA 2 and PIXELS.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

The classics.. STAR WARS, BLADE RUNNER, ALIENS.. all the greats from when I was a kid.

JURASSIC PARK also sticks out as a milestone event for me as it seemed to elevate what was possible, leaping ahead of everything before it in terms of believable characters.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Sony Pictures Imageworks: Official website of Sony Pictures Imageworks.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2014