Back in 2017, Paul Lambert explained the work of DNEG on Blade Runner 2049. He then worked on First Man. Today he talks to us about his new collaboration with director Denis Villeneuve.

Tristan Myles began his career in visual effects in 2003 at The Jim Henson Company. He joined DNEG in 2004 and worked on many films such as John Carter, The Dark Knight Rises, Interstellar and Blade Runner 2049.

Brian Connor has been working in visual effects since 1994. He has worked at numerous studios such as Dream Quest Images, ILM, Scanline VFX before joining DNEG in 2014. He has worked on a wide range of films such as Pearl Harbor, Transformers, Wonder Woman and Godzilla: King of the Monsters.

Robyn Luckham started his career in visual effects in 1999 at Framestore. He then worked in many studios such as Weta Digital, ILM, Digital Domain and DNEG. His filmography includes films such as The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Avatar, In The Heart of the Sea and Togo.

How did you get involved with this movie?

Paul // I had stayed in contact with Denis after working with him on Blade Runner 2049 and he asked me if I would be interested in working on Dune and I said “of course!”. I joined the movie for prep in September 2018.

Tristan // Having worked with Paul on the last couple of movies together, I was thrilled to be asked to join him on his next project, none other than Dune. I started work on preliminary tests in October 2018 to help with the prep for the movie, I then went on set for the first day of shoot prep, March 12th, 2019 (which was coincidentally my 40th Birthday – what a great way to celebrate that date!)

Brian // I worked with Paul on an early DNEG–Vancouver show. We all made it happen despite all the obstacles which is probably why he asked me to join the DNEG Montreal team to work on none other than DUNE! I packed up my things, rented out my new apartment and moved out to Montreal via the Canadian Pacific Railway. I actually read two books, if folks remember what they are….

What was your feeling to be involved in such an iconic project?

Paul // Blade Runner 2049 had been such an amazing experience, that I knew that with Denis at the helm again Dune would be even more so. I knew it was going to be a tough project due to the history of telling this story on the big screen, but I also had 100% confidence in Denis’ vision for the movie.

Tristan // I was super excited about being involved on this project. I’d been a big fan of the Dune novels growing up, my father got me into them as he’d been reading them previously – and to see those ideas and visions come to life for the movie was absolutely amazing.

Brian // Well of course I was honored to work on a motion picture adaptation of the classic novel by Frank Herbert with Paul Lambert and Denis Villeneuve! I did a lot of reading in my youth and read the series along with most of the Sci-Fi/Fantasy of the time. I was happy just to have a seat at the table for this once-in-a-lifetime project.

How was this new collaboration with Director Denis Villeneuve?

Paul // Well I had worked with Denis previously on Blade Runner 2049 and he had had a great experience with DNEG, so there was already an understanding of how he liked to work.

What was his approach and expectations about the visual effects?

Paul // He wanted everything to be as grounded and photoreal as possible. He never wanted a VFX shot to take you out of the movie. Working in close collaboration with DOP Greig Fraser, Production Designer Patrice Vermette and SFX supervisor Gerd Nefzer, we had to come up with a multitude of techniques during the shoot to provide the best basis for the VFX work in post. Lighting was exceptionally important to recreate the hot arid bright desert environment. We were never going to try and simulate daylight inside a studio and you can’t get enough brightness from an LED screen so we always favored shooting in sunlight for the exterior scenes. We used an abundance of SFX on the shoot for dust and sand to simulate the inhospitable environment of Arrakis. I’m a big fan of harder composites with all elements shot together rather than building things up in layers much to the discomfort of the actors… and compositors!

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

Paul // I had a great producer in Brice Parker. Very calm and collected. Honestly there was never a panic on the show about a particular sequence or effect. We went over budget on some sequences which were balanced by going under budget in others. Brice allowed Denis to keep his vision throughout the movie.

Can you tell us how you split the work amongst the vendors?

Paul // DNEG was the primary vendor doing a lot of the heavy lifting – from digital creatures, digital humans, digital environments, massive FX simulations to 100% CG shots. Wylie Co handled all the post-vis and in-house work along with hundreds of blue eye shots, the Hologram and Cemetery sequences. Rodeo also contributed a handful of beautiful Caladan and Geidi Prime establishing shots.

Where were the various exterior sequences filmed?

Paul // The shoot was a total of 115 days. We shot in Hungary, Jordan, United Arab Emirates, Norway & California.

How did you enhance the various locations?

Tristan // Many of the interior sets were extensively built to eliminate the need for any greenscreen usage. Any extension work that was needed was generally in extending the set upwards, or off in the distance for any corridor extension work.

For some scenes that were only a partial build, we employed the use of an iPad on set that was running DNEG’s proprietary visualization software, which used the Augmented Reality function on the iPad itself. This meant that we could build in 3D the full environment in question, then overlay it on the actual set, view it on the iPad screen in the set location, and walk around the set and be able to see what it will look like once the extension work was done. We also had a function that allowed for the shifting of the Sun position in the sky for exterior scenes where shadow casting was important. Compositionally this was important too so that shots could be framed more accurately.

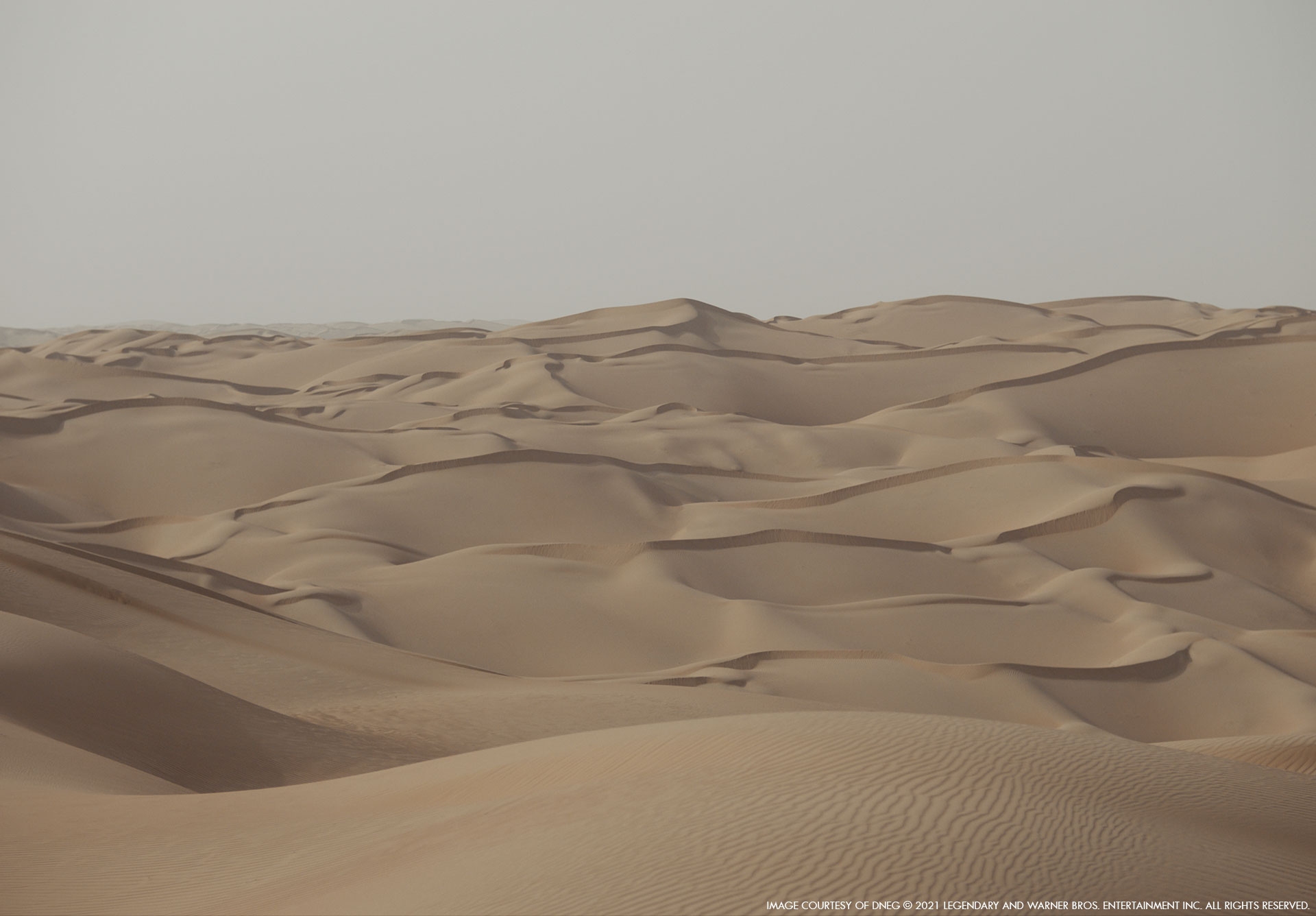

For the exteriors in the desert scenes, the deserts of the Wadi Rum area of Jordan were an amazing canvas on which to expand upon. Wherever possible we kept the sand from the plate, then recreated it maintaining its shape and look for when we needed to deform it or break it apart, whenever the Sandworm was in the scene. Extensive clean-up was also done on these desert plates as they had a scattering of plant life on them which needed to be removed as there is supposed to be no plant life in the deserts of Arrakis.

Paul // The iPad was also a great visual aid for eyelines for the actors. It was hard to convey to people just how enormous the worlds had been created by the production designer Patrice Vermette.

Brian // For the Space Port and other locations, we shot on a huge, newly created backlot at Origo studios in Budapest. It was a truly massive space that was surrounded with distant walls that angled backward so they were naturally lit by the sun. The walls and ground were all painted with a special sand color, so all the bounce light feels natural. Instead of bluescreens, we used ‘Sandscreen’ which, when the image is inverted, returns a bluescreen that can be extracted to get all the fine detailed edges. This worked very well and I think made a difference to everyone on the crew. Having 40x Sandscreens to move around and place where needed felt less invasive and distracting to the cast and crew than a typical bluescreen. Something I think Denis and the cast appreciated as much as we did.

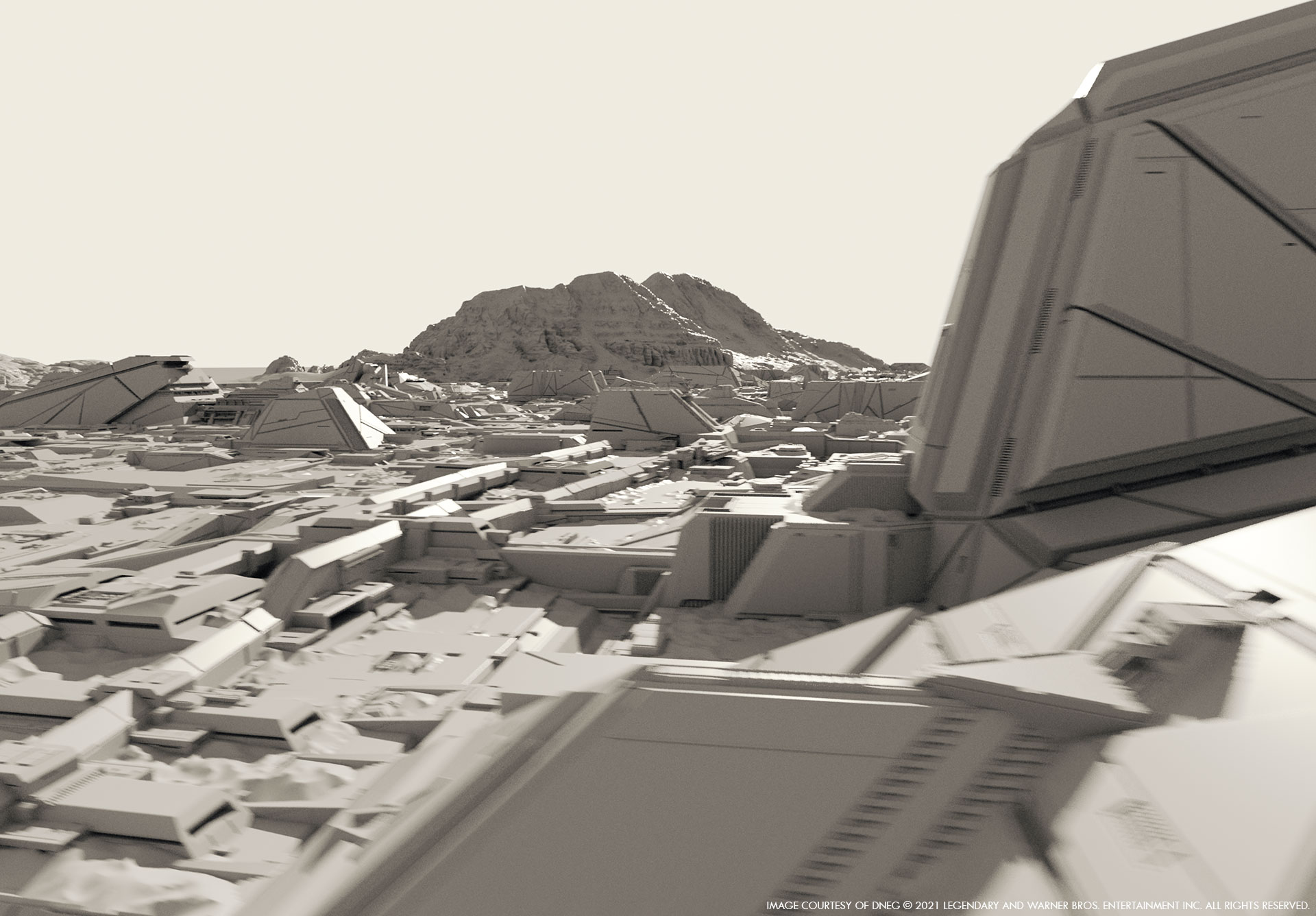

Which environment was the most complicated to create and why?

Tristan // For me, the most complicated environment to enhance and replicate was the desert. As it turns out, you can never have too much sand! Maintaining the scale of the sand at the sheer volumes that we had to because of the size of the sand worms and how much they displaced, whether below the surface or above it, was tricky and a special system had to be created to accommodate this when it came to simulating the sand FX and then to render it. Scale was absolutely key. If the sand grains looked too big, the Sand worm and even the environment started to look small.

Brian // The Space Port and Sandstorm environments were two of the most complex ones for us. For the Spaceport we had to create the massive area where all the huge Atreides Spaceships, Ornithopters, Spice Harvesters and Containers are located. Patrice and Denis provided Paul and the rest of us with some truly amazing, fully-realized designs of various locations within the Space Port. They became integral to the design and building of all the assets we created. It is not an easy task to create such a massive, desolate environment and have it feel real. We had to populate it with CG crowds, soldiers and break up edges with miscellaneous props to make sure there were few straight lines. Even the ground required its own look development as what looked great at ground level, did not always work when seen from an aerial point of view. Once we got all that working, Tristan and his team enhanced and destroyed it in spectacular fashion…

The movie is full of various ships with great design. How did you work with the art department?

Paul // Usually concept art acts like a springboard to more ideas but Patrice and Denis had spent the better part of a year creating these amazing worlds. Denis was so happy with these concepts that we stuck very closely to them – we built the physical sets based on these images as well as the CG assets. There were of course additional assets to be created after the shoot in post and we kept in touch with Patrice to make sure any new work was still in line with the overall feel of the movie.

Can you explain in detail about the impressive Ornithopters?

Paul // Patrice had designed these massive flying contraptions and had them built to be used in camera. I remember visiting BGISupplies in London when they were being built and was truly impressed by the scale of these things. I was also very concerned about the number of reflections in the cockpit as I knew we would need to be careful shooting around the Orni when on set. We kept the glass in throughout the shoot making sure the crew shifted away from all the reflections – a little challenging but it worked out great! One of them also had a fully functioning hydraulic ramp to enter and exit the vehicle. The built Orni’s were just under 12 tonnes in weight and one of them had to be flown to Jordan using a huge Antonov cargo plane. We lifted them onset by cranes to simulate taking off and landing and SFX blasted them with sand and dust to simulate the downdraft from the added CG wings. DNEG built fully CG versions too to be used for taking over from the real machine when the camera went wider and when going into full flight.

How did you handle the wings animations?

Robyn // The Ornis were the first big challenge. For an animated performance they would appear the most in the film and had to feel seamless and utterly real. We had a motion sketch from Patrice, which gave us the basic principles of articulation. Really I felt for Denis these had to be very real, not science fiction if you know what I mean. It was key for him that they had a big sense of weight and logical mechanics.

We had to approach the wings with the question ‘could these actually lift the weight of this giant fuselage?’ Let’s try and make it work.

The animation team studied many helicopter motions, iconic film vehicles, and natural creatures. The Ornios were huge and could fit a blackhawk inside of them, they needed to display that kind of power. We started very much with a slower wing beat, much like something out of Ghiblis ‘Laputa’ – this looked graceful and elegant, however it wasn’t that militaristic sense of real I wanted for Dune.

Denis liked the influence of creatures and talked of an impression mosquitoes gave him when he was filming in the desert. We looked at bees, hummingbirds and dragonflies and started to realise that these wings needed to beat at incredible speeds to actually ‘feel’ that they could work. Much like a hummingbird/dragonfly, but that blur you would associate with the blades of a helicopter or propeller.

Once blurred, we lengthened the blades to again aid that sensation that they would hold the weight of the body and still be maneuverable. We looked at the amount of rotation the wings would have up and down so it would create a blur presence that could hold the Orni in the air.

We would set rules for not separating the blades individually too much, in order to keep a large area blurred so the wings feel powerful in flight, but still be able to have some base rotations and show that they can be very versatile in movement of the overall craft. Each individual blade doesn’t intersect any other one at any point, even though they beat many times a second. They each also move in a figure 8 much like a bird.

Last major adjustments were to the character of the blur within the wings beating itself. The sub sampling was as high as we could get it at DNEG, in order to produce a blur and distinct ‘blade signature’ within the blur itself.

It was a fine balance of showing the power and weight, but articulation that a highly agile Ornithopter has. Motions and turns with the blades were all very considered. Took a lot of testing, but once all of this was put together, we produced a motion ‘bible’ for Denis that he was incredibly happy with, and so were we!

Once we had established the core principles of motion for the blades we applied the same logic to the Harkonnen Orni and the 2 seater that Paul and Jessica fly. The Harkonnen one was tweaked a little for larger spread of blur as they needed more rotation to keep them airborne as they were slightly heftier, but only had 6 blades. Heavier and less maneuverable. The 2-seater had a little faster blades and could have more agile movements as it had less weight to keep in the air. They were all based on the same established mechanics, which I assumed if they were real they would have been built this way as therefore all felt in the same universe.

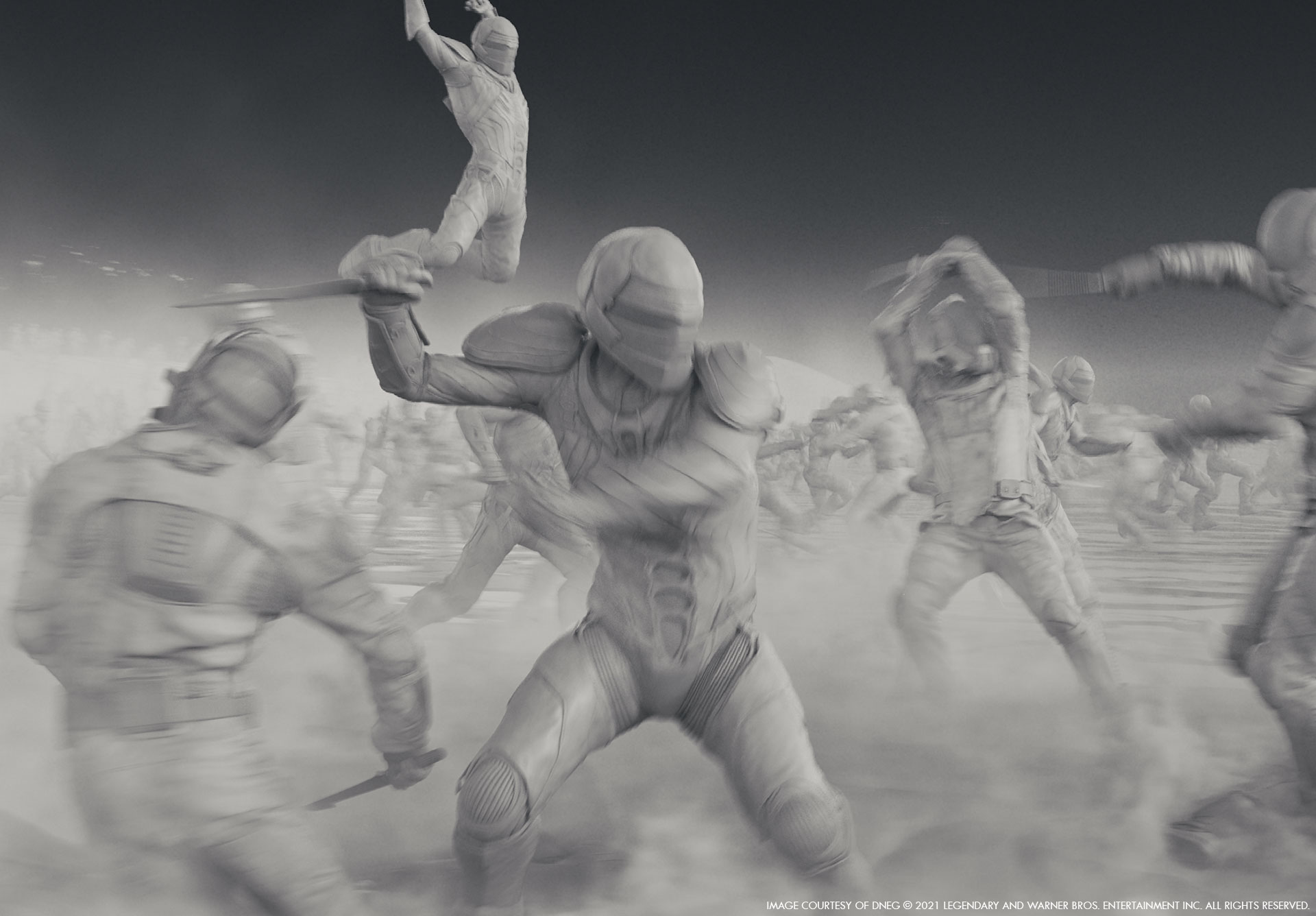

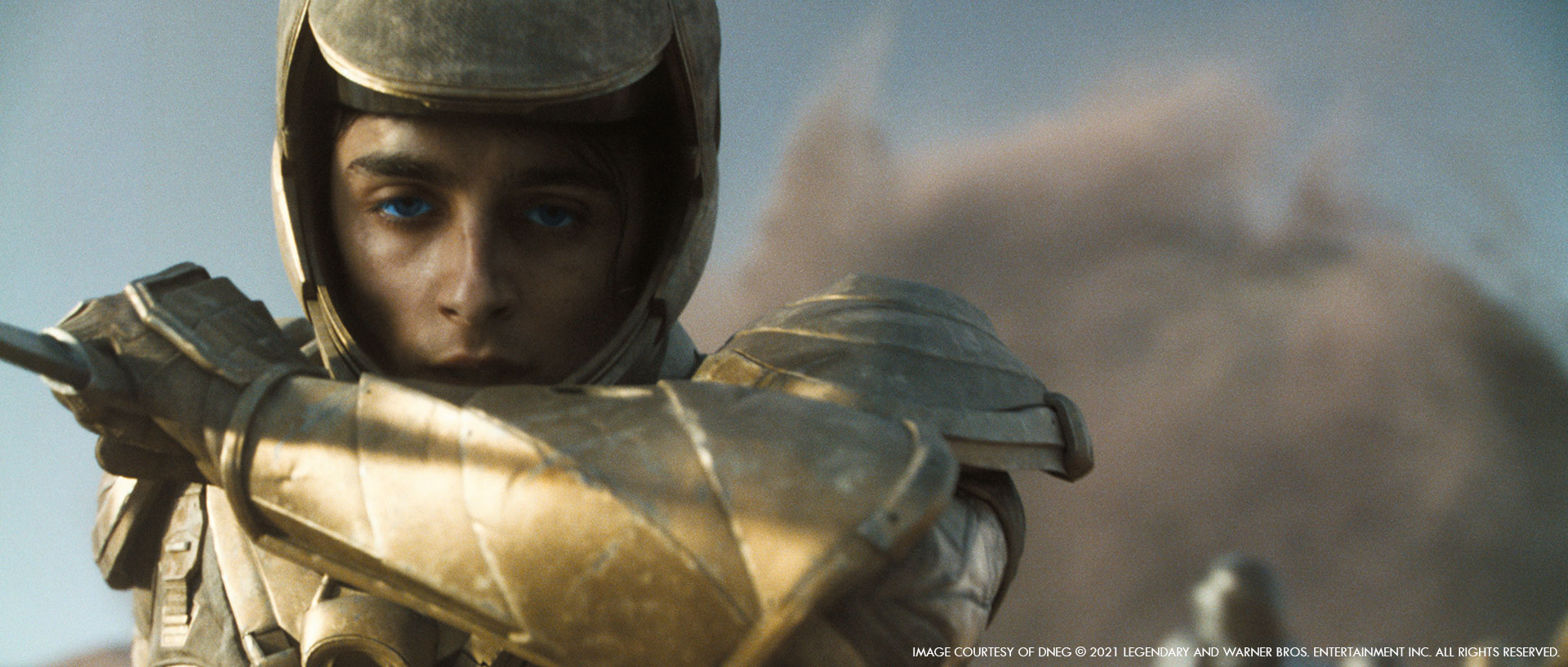

How did you design and create the body shields?

Paul // We landed very early on during pre-production of an idea of using past and future frames. These were blended together and then artists artfully painted back the original plate or augmented the blended image frame by frame to add more of an organic feel. It was only in post with the edit of Paul training with Gurney that we added the red and blue coloring. We found that the fighting was so intense that it was hard to figure out who was striking who so by adding the blue for protection and then red for penetration the fight was more easily understood.

Tristan // At DNEG in Vancouver we had a small, skilled compositing team dedicated to working on these body shield effects, painstakingly painting the areas requiring the shield effect across the sequences to see how it plays, then going back in and tweaking areas that didn’t quite work. The key was to make the shield work in harmony with each movement when there was interaction between the characters and their blades, but not have it affect whole areas. It had to be controlled in an artistic way so as not to confuse the whole image, we had to keep the key moments of action visible.

How did you help Baron Vladimir Harkonnen to fly?

Paul // That was all practical with only some VFX cleanup. We had Stellan strapped to a mini crane and for some shots a stunt player on wires. That with creative camera angles worked really well.

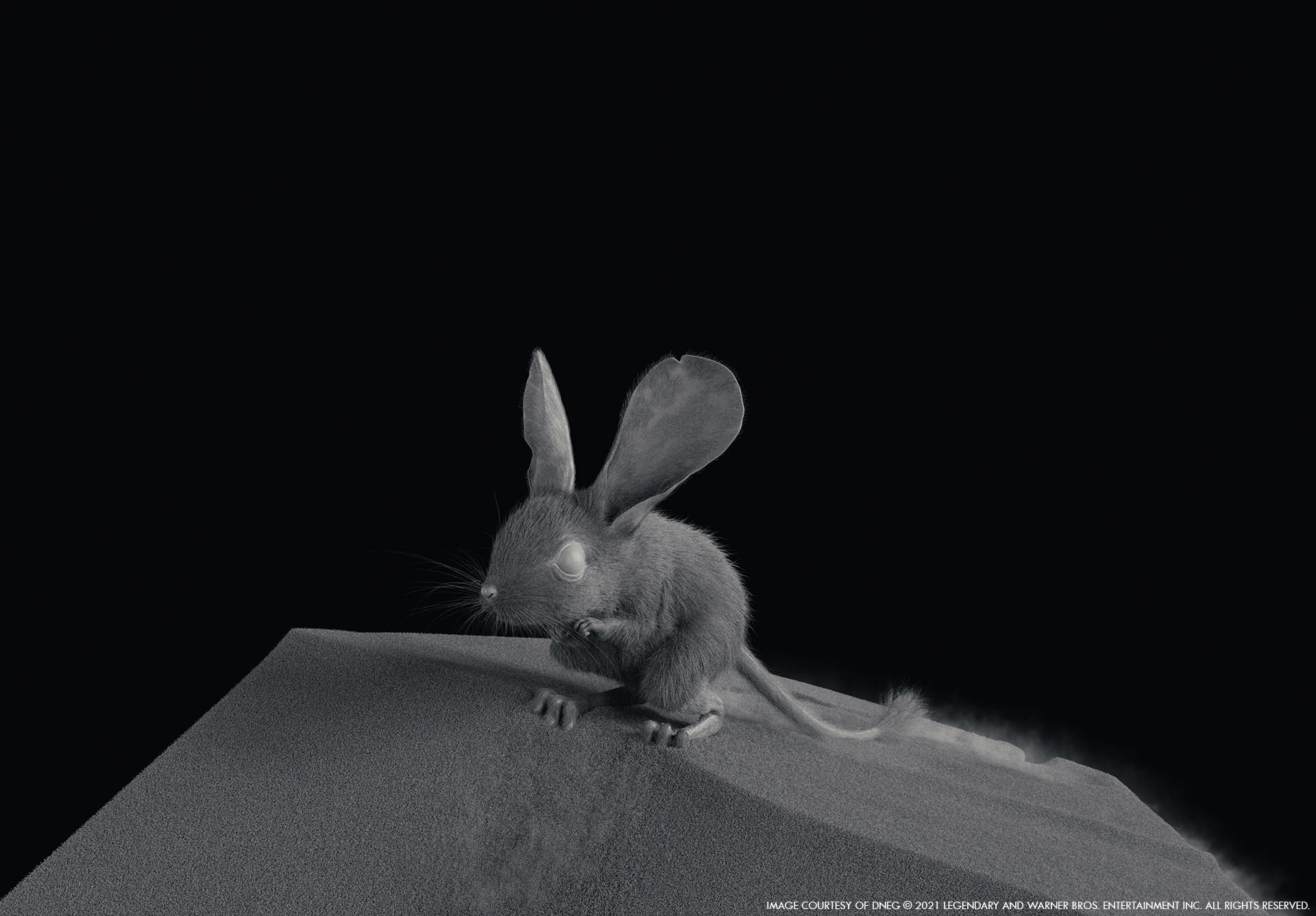

Let’s talk about the iconic sand worms. What was your approach to them?

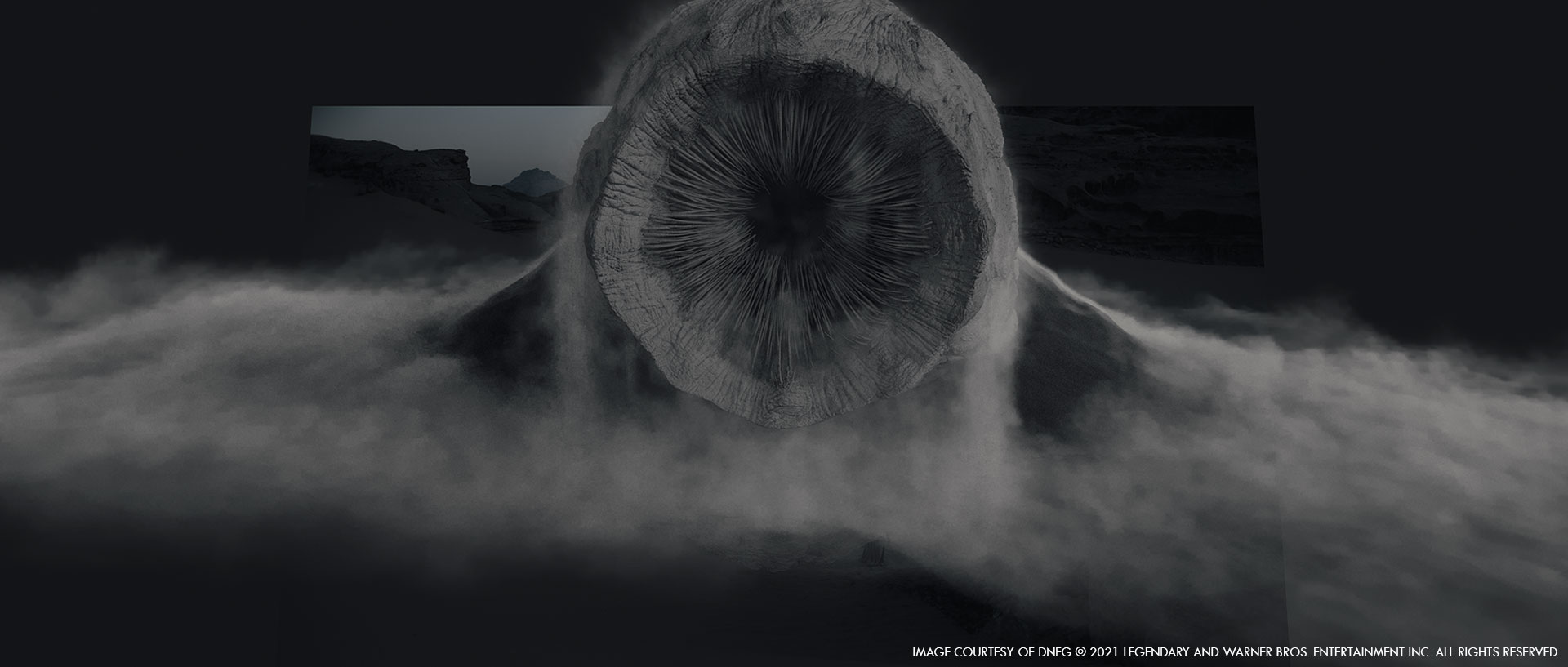

Tristan // There are only a small number of sequences that feature the sand worm in the movie, and the idea was to keep the mysticism surrounding the worms and what they looked like as shrouded as possible until the end of the movie. So for sequences where the worm is involved with the action in the earlier parts of the movie, sand played a massive part in obscuring the worm and we had to carefully orchestrate how much sand is covering the worm mouth (as that was the only part that came above ground in those early sequences) and how much we could reveal.

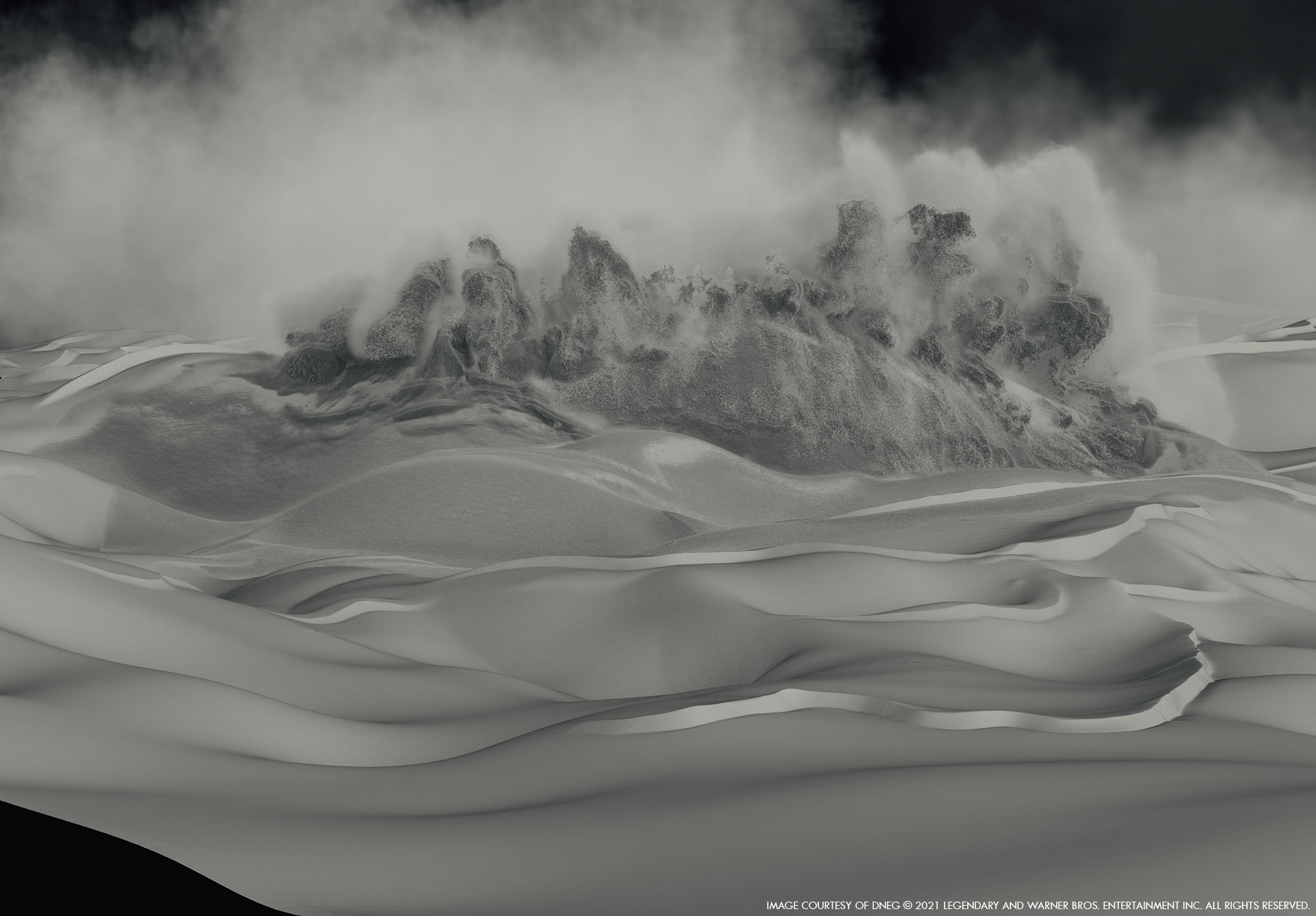

Later in the movie, movement above the ground where part of the Sandworm is above the sand, we leaned into the ‘Jaws’ homage and played the sand almost like water, parting in waves in front of the worm as it ploughed through the sand towards Paul and Jessica.

Due to their massive size, how did you handle the scale and animation challenges?

Robyn // For the animated performance of the Sand worm we wanted to give it the utmost respect, as for a science fiction creature it’s one of cinema’s most legendary. I researched with the animation team every known worm and limbless reptile on the land and in the ocean, and in fact found fossils from Asia that were also of influence. Patrice and Denis again provided fantastic illustrations and detailed designs that they wanted to rationalise, it was then a huge process of ‘frankensteining’ many creatures together and getting that level of scale and believability. It was also critically important with creatures of this size and gravitas that they were also still cinematic – we couldn’t take 4 hours to move it across the screen even though the Worm was about kilometer long. Much like the previous film creature I have done (Heart of the Sea / Moby Dick), the phenomenal FX work that would wrap around the Worm would give us the indication if we were too fast or slow in the movement, It was as much of a part of the Sand worms character as the body motion itself.

We experimented with body undulations pushing itself through the surface like an earthworm, slight side to side motions pushing over the mounds much like the muscles of a snake would use and even the hard skin patches itself to pick and push it over a surface, like haired caterpillars do and some sub surface dwelling creatures. Ultimately these became too scientific or biological and lost the sense of powerful grace and majesty that I was trying to achieve in the Sand worm. We took a holistic look at the sand worm and its environment and it became more obvious that this creature was less of a Worm and more of a Sand Whale in a vast ocean of desert. It would power through and carve the sand like a sea, cresting, breaching, and smashing its way through the sand but with complete control over it. This was a major step in getting the character and was very successful. Once we had established this language and essence for the sand worm, we could work all the intricate biological laws/muscles/skin and mouth performances from our research to add to the believability.

How did you manage the sand interactions with the worms?

Tristan // As mentioned previously, the FX team had their work cut out for them with the sheer scale and size of the scenes they were working with so a system was created to allow us to see approximately how the end result would be for the movement and behaviour of the sand that was a bit more agile to work with. The animation team responsible for bringing the Sand worm to life and moving the creature through the sand would get something that was looking good, then this would be handed over to the FX team for their simulation and augmentation work on the sand around the creature. Then there would be some back and forth between the Animation and FX teams to refine the movement of the worm that gave us the sand interaction that we were looking for. From there, full resolution simulations were carried out and renders created by the lighting department to get the final look.

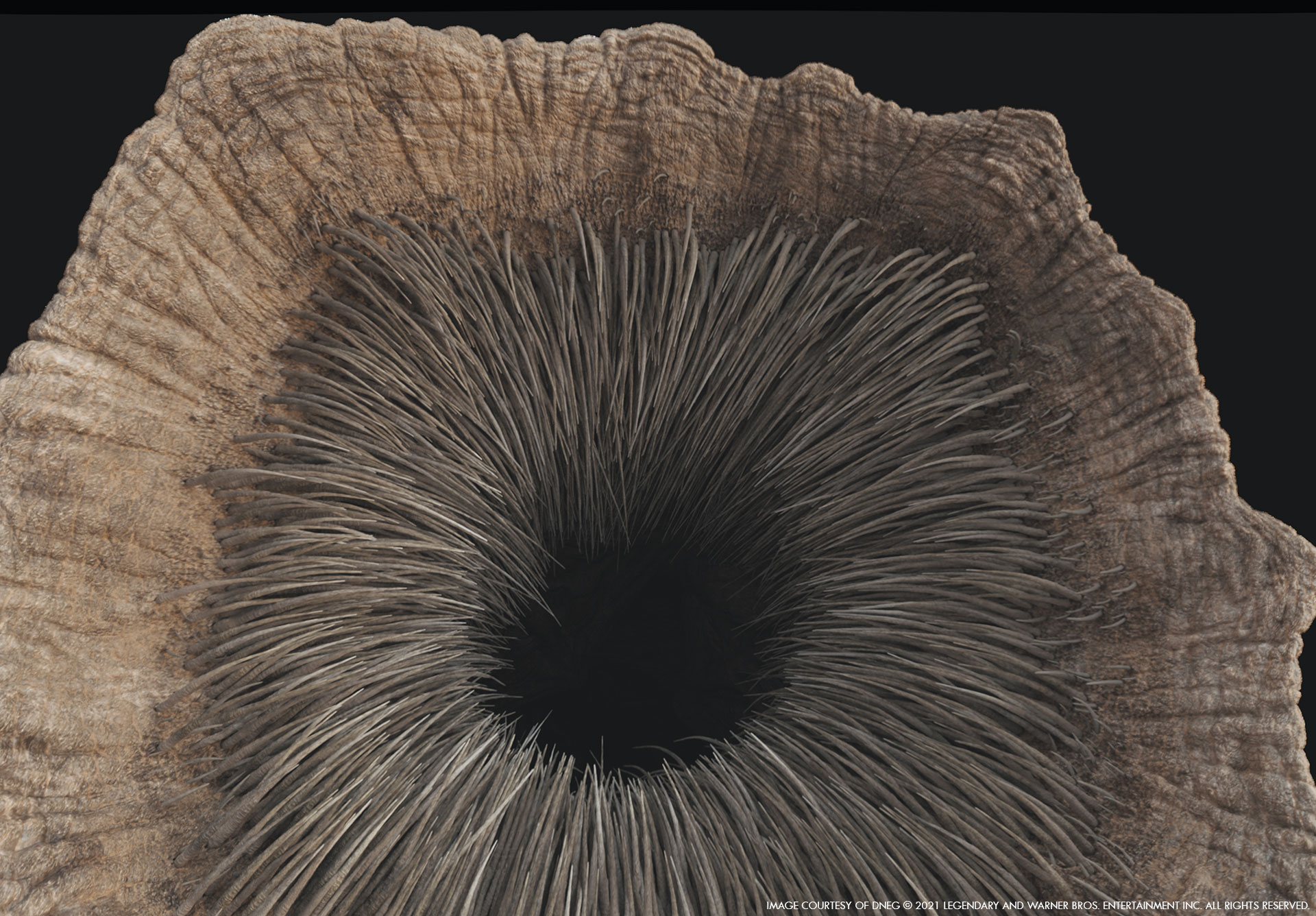

Can you tell us more about the worm mouth animations?

Robyn // The worm’s mouth was probably the most exciting design that Patrice delivered to myself and the animation team, I was so enthused to get it to work! Again it leant into the principles we had developed with the body motion, that the Sand Worm was a giant sand whale, as it had been designed with a mouth made of a huge circular Baleen. Baleen are used by whales to allow water to pass through them but filter out the fish and creatures it would like to consume.

For our Sand Worm, first we stripped the mouth section down to nothing and built it up through principles of muscles that could actually perform the motions that we need of contracting and opening and closing a large circular mouth. This was influenced by human mouths using orbital muscles and attached muscles to open, curl and close. The Baleen would articulate, and the hundreds of giant curved ‘teeth’ could lie flat to the mouth to allow large objects down, but also move forward and side to side to ‘bristle’ for any sense of air motion coming in and out of the mouth. This could also give Denis and the sound designers a great opportunity for creating any horrific ‘voice’ to the sand worm. The throat was also incredibly interesting, and we studied footage of the inside of a ‘beat-boxers’ larynx on how the throat would be affected by sound. There was a designed performance contrast from the rough and hard external skin to the exposed and terrifying muscles deep inside the Worms mouth. These muscles we all rationalised from human throat muscles and could feel connected and driven from a real creature.

The finished effect was a highly articulate muscled mouth with realistic logic driving its animation, whale-like baleen ‘teeth’ that could move independently for function or reactive to sound and a throat motion that was grotesque and terrifying but also based on muscle logic. With the amazing creature work in creating the detailed muscle rules, we had such great flexibility with what performances we could achieve, I once bragged that I could even deliver one line of dialogue from the sand worm’s mouth!

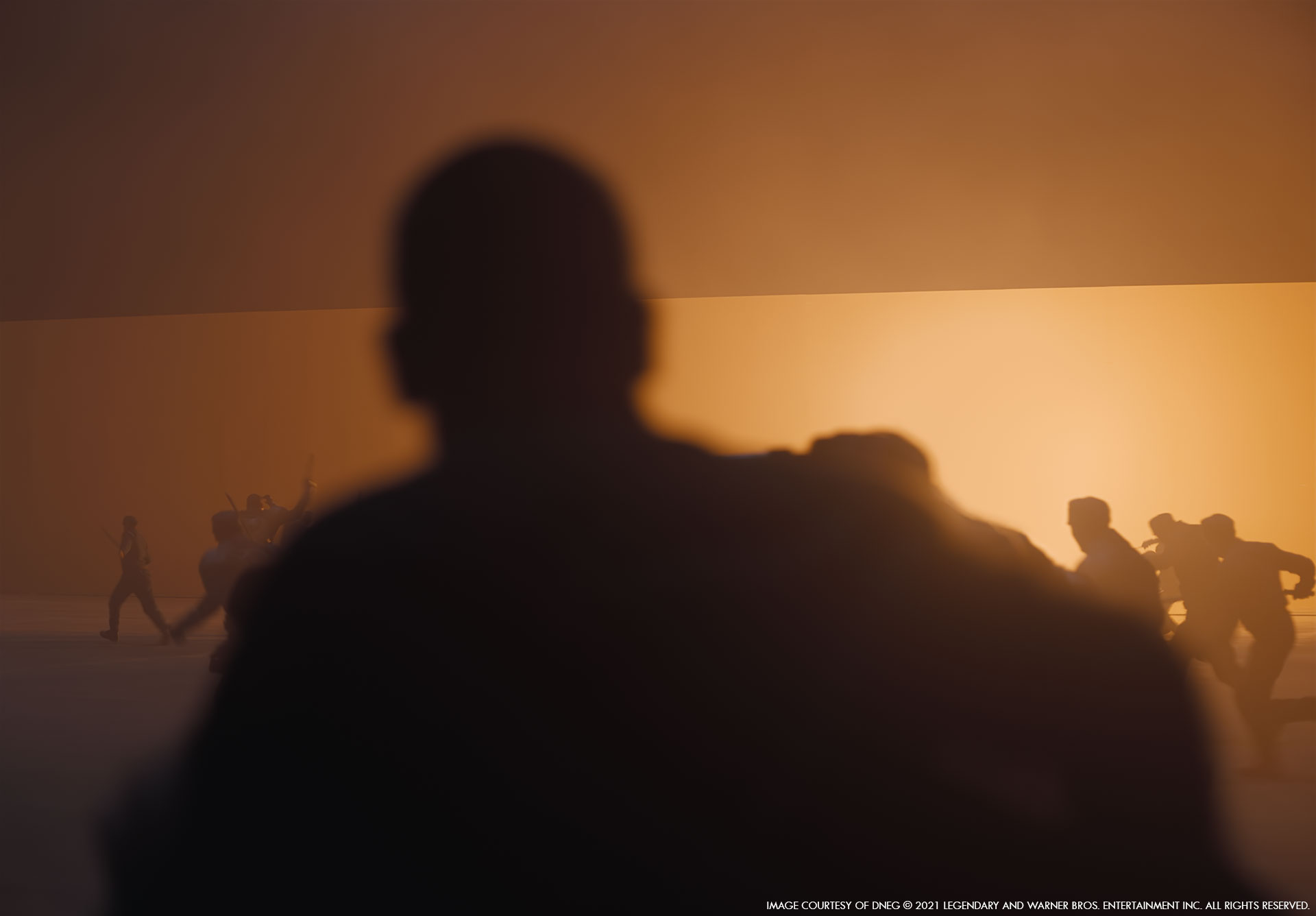

How did you manage the big FX sequences such as the sandstorm and the Harkonnen attack?

Tristan // For the Harkonnen attack on Arrakis, one of the key areas that we knew we had to get right was the look and feel of the explosions. Lisa Nolan, one of our FX Supervisors, and her team spent a lot of time on the look and behaviour of the explosions themselves. A fair number of practical fire and pyrotechnic effects were used during the shoot, so our FX explosions had to match with these seamlessly. Breaking apart the huge ships from Caledan was a big undertaking too, requiring the detailed modelling of the interior structures of the ships which were going to be ripped apart by these large explosions and come crashing down onto the ground of the Space Port. Chris Phillips and his team were responsible for handling these massive simulations and ensuring that all the forces were to the correct scale so that they behaved realistically. We also had to generate the look of the shield effect which was used on the personal shields, but make it work at scale which required it’s own setup in FX with some deft handling of the layering at the compositing stage.

Brian // For the Sandstorm we shot our actors on a gimbal that was capable of doing full 360-degree rotations. We had placed this gimbal in an enclosed area and then literally just blasted the canopy with dust and sand to produce the swirling texture you see in the interior shots. In post we added additional larger debris to add to the sense of peril. The wider shots were all CG using the look of the texture swirls as reference that we had shot on set. Paul provided us with some fantastic National Geographic reference of massive sandstorms in Africa and one swallowing the city of Denver. We used them to get the right scale and look of the Sandstorm.

The Sandstorm was a difficult environment to create requiring massive particle simulations. The outside face of the Sandstorm was different from the interior which was different from the top. We treated it as such and blended between the methodologies when needed. The all-encompassing sandstorm was literally kilometers in depth, which Paul and Jessica use to escape the pursuing Harkonnens. This required our FX team to come up with more efficient ways to create and iterate the look of the Sandstorm. It also required us to upgrade and optimize our distributed rendering farm, where each simulation used large chunks of rendering and storage space.

Paul // One of the funniest visuals is seeing the 1st AD appearing from this sandstorm enclosed area completely covered in dust and sand. He was literally orange from head to toe!

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

Tristan // For me, the most challenging sequence was the worm chase sequence, where Paul and Jessica have to run from the worm that chases them. It was challenging across all departments, FX, animation, environments, lighting, and compositing. This sequence is the first time that you get a good look at the worm above ground, before this point in the movie you’ve only had glimpses of its mouth through a layer of sand, so the first step was to get the movement right, and there’s a moment as the chase starts where the worm first breaches the surface of the sand and bee-lines for Paul which has a nice nod to the movie Jaws as the worm ploughs through the surface of the sand, kicking up volumes of sand either side of its mouth as it churns through the ground towards Paul.

Another component of this sequence was the opening of the mouth above the ground, and what sound the worm makes and therefore, what throat shapes should form to create this sound, and how should the baleen (what we called the worm teeth) move and react to this. Lots of complex controls were built into the creature rig to help facilitate these challenges that faced the animation team.

Then throughout this sequence we’ve got absolutely huge volumes of sand data which is being pushed around by this worm and deforming the landscape around it as it moves. Here the FX and the environments team worked in tandem making sure that the two setups influenced each other to create the smooth sand flowing through the deforming sandscape that you see in the finished sequence.

The final stage is lighting the scene so that the FX and creature work sits into the plates which were shot for the action which involved some per shot lighting tweaks to make this work. The compositing team then took these renders and blended them with the live action plates to complete the shots.

Brian // There were many ‘most challenging’ sequences in this film. It’s hard to pick just one but I would say the Atreides arrival at the Space Port was one of the longest and most challenging. It set the tone for Arrakis and required multiple DNEG teams to create and manage as the assets were used across locations.

If you asked me to pick one of the most difficult shots, for me it was the Atreides Flagship and Spaceship rising out of the ocean in Caladan. The key to believable visual effects is having reference to use as a guide. It was difficult to find something which showed the mass displacement of water. Paul ended up finding reference footage of huge masses of glacial ice as they overturned after parting from a main glacier. As you can imagine, this required a significant number of iterations to get a realistic sense of ocean water performance while maintaining the correct scale. The Flagship and Spaceships are huge so having the water cascade down the sides and back while displacing the ocean surface was very challenging. We had our FX supe and another FX artist spend lots of quality time (and weekends) on this shot alone.

Did you want to reveal to us any other invisible effects?

Paul // From shooting the interior Ornithopters on the highest hill outside of Budapest for natural light, burying a vibrating plate in the desert to allow our actors to sink into the sand to bouncing sunlight into cavernous spaces we really tried to come up with the best techniques on set to give us the best plates to be augmented in VFX.

Another example was a technique to give us a realistic visual in the Hunter Seeker Hologram sequence. DNEG had developed and supplied a real-time tracking solution so that we could figure out where Paul was on the set. Denis had already approved the creosote hologram bush which Paul would be hiding in so we split this 3d asset into thin slices and then projected that slice onto Paul on the set. As Paul moved around, a different slice would be projected giving the impression that Paul was moving through the hologram. This gave us the ideal interactive pass on Paul’s skin and clothing which WylieCo then composited the rest of the CG bush around him.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

Paul // Nothing really stands out as being too troublesome. We made sure we started very early on with the sand simulations as we all knew that was going to take a while to get right.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Paul // There are so many. I particularly liked how the Salusas Secundus sequence came out as it was a particularly challenging shoot with rain and sunlight at the same time. The attack on Arrakeen was just epic in scale which shows off a lot of the work as well as the worm attack on the spice crawler.

Tristan // As Paul says, there are so many to choose from. I think personally I like the spaceport attack sequence. A huge amount of work went into that sequence with lots of explosions and getting the absolutely massive craft to explode and crash in believable ways. It also involved coming up with a way of conveying the Holtzman personal shield at a ship-sized scale, deflecting and ultimately collapsing under the barrage of the Harkonnen assault.

I also like the sequence that sees Duncan flying through Arakeen as he attempts to escape the Harkonnen siege on the city. And of course, I love the Sandworm chase and subsequent reveal sequence towards the end of the movie. I think the team did an amazing job of conveying the immense scale of this creature and the massive volume of sand which it displaces in its path.

Brian // Well as any parent would say, “I love all my children”. I am proud of all the work we did. Each team really put in their collective hearts and souls (and lots and lots of time) into Dune and I think it shows up on the big screen.

If I had to pick from the many locations we created, I think all the pomp and circumstance that happens when the Attreides arrive at the Arrakeen Space Port was one of my personal favourites. We really tried to convey the feeling of a massive space that somehow melts into the background and helps tell the story and set the tone for Arrrakis.

What is your best memory on this show?

Paul // So many it’s hard to single one out. It was such an enjoyable collaborative experience that will be hard to beat.

Brian // This movie is filled with many great experiences on-set, and with DNEG the team, all of which make me smile every time I watch this epic film….

How long have you worked on this show?

Paul // 2 years and 3 months.

Tristan // About 2 years, 2 months.

Brian // 1 year and four months.

What’s the VFX shot count?

Paul // All in all, almost 1700 VFX shots were featured in the movie.

What is your next project?

All // Hopefully something sandy….

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

DNEG: Dedicated page about Dune on DNEG website.

HBO Max: You can watch Dune on HBO Max.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2021