Back in 2020, Doug Larmour offered insights into the visual effects process for The Alienist: Angel of Darkness. Subsequently, he contributed to the visual spectacle of The Wheel of Time and House of the Dragon.

How did you get involved on this series?

I got contacted by one of the Executive producers; David Tanner from Turbine Films towards the end of 2021 when I was still working on season one of House of The Dragon. I read the first two scripts and was blown away by how good they were. I then had an interview with Michelle MacLaren and thankfully we all got on.

How was the collaboration with the showrunner and directors?

To be honest, I couldn’t have hoped for a better relationship with either Peter Harness (the writer and showrunner), Michelle Maclaren (the supervising Director), Oliver Hirschbiegel or Joseph Cedar.

Although guided by Peter’s imagination and Michelle’s singular drive for excellence, this was a very collaborative creative team on the production side of things where everybody’s expertise was mined in order to create a marvellous and spectacular drama series. Other than the directors, Andy Nicholson (production designer), Markus Forderer (DOP), Frank Lamm (DOP), Yaron scharf (DOP), Martin Goeres (Stunts and FX), Uwe greiner(gaffer), all the 1st ADs and every department were all incredibly helpful in pulling off some very demanding VFX. Its very easy for directors and other dept heads to focus on the drama and the problems that they physically see in front of them and not leave much thought or time during the shoot to how the VFX will pull everything together in post. However, from the first day of prep the needs of VFX were paramount, especially for all the space, snow and trippy reflection scenes.

Then during post the collaboration just grew with the directors as they put great trust in our team to deliver the quality, versimilitude and nuance that the show needed in order to draw the viewer into our strange world.

How did you organise the work with your VFX Producer?

We had two VFX producers on this show; Jakub Chilczuk looked after Prep and shoot, whilst Antony Bluff saw us all through the long post schedule. During prep and shoot, Jakub and I went through the scripts and called out where we thought we would need VFX. He and I discussed the approach to take and then I would tackle the specific design and details of how best to shoot and acheive the desired effect with the directors and shoot team, while Jakub organised the budget and had a lot of chats with vendors and the production executives to make sure we were all in line with the budget. During post again the split was fairly similar in that I dealt with the more hands on creative details with the vendor supervisors, whist Antony took the brunt of the financial and organisational duties. I must also mention at this point Russell Forde (senior VFX Production manager) and Sandra Eklund (VFX Production manager) who stuck with us all the way from prep to final delivery and were invaluable and integral to all the VFX decisions (creative and managerial).

How did you choose the various vendors and split work amongst them?

We chatted to a lot of vendors from the very begining of prep so as we could make an educated and reasoned estimate of what the VFX would cost. During this process we discussed the various approaches we might take and based on those chats; any previous working history; similar work these vendors had done before and of course costs and tax breaks we made our choices. In the end One of Us (London and Paris) took on exterior and interior space (including zero G fire, blood, re-entry and destruction), Outpost VFX (UK) took on Baikonur exterior and interior (which included taking Templehof Airport from the middle of Berlin to the desert of Kazakstan, the CG helicopters, a lot of the screens that you see inside the numerous mission controls and LA in the rain) while Jellyfish Pictures took on Snow and the cabin fire (which was enough shots to fill an entire episode). Later on we added Mathematic in Paris (who built St Sergius, threw a digi double of Ian Rogers off the back of a cruise ship and helped build Star city in Moscow); Spectral in Budapest (who helped with a lot of CG Breath work and reflections), Studio 51 in India (who dealt with the brunt of all the wires in space); and Dazzle Pictures in Belgium (who also did breath, reflections, fire and screens). We also had a very small but strong in house team.

What is your role on set and how did you work with other departments?

Primarily my role on set is to make sure that whatever is shot by the crew is shot intelligently and with the final shot including VFX in mind. Sometimes, like with the EVA sequence in episode one, this requires that I have talked with the director and created a previs animation sequence with them for everyone to follow, then liaised with the production designer, DOP and stunt department months in advance to make sure we have everything in place in terms of set, wire rig and green or blackscreens for us to shoot the plates we need. Other times it’s just making sure the we don’t leave anything silly in shot like a set light, crew member or wrong prop which will need us to paint out later and be a waste of resource. Its also my job to supervise the on set data team and advise them on when we might need to get more specific data or set up eye lines and tracking markers. On a show like Constellation there were very few completely non VFX days.

Can you talk us through the process of recreating the International Space Station (ISS)?

When we first read the script, it was obvious that space was going to be one of our biggest challenges, especially when you consider that we had to film sequences inside and outside the ISS and would have to simulate a zero G environment. The production were very smart in that they had managed to persuade Andy Nicholson to come on board as the production designer as he brought with him a wealth of knowledge and experience that he had gained from being the production designer on ‘Gravity’ (2013).

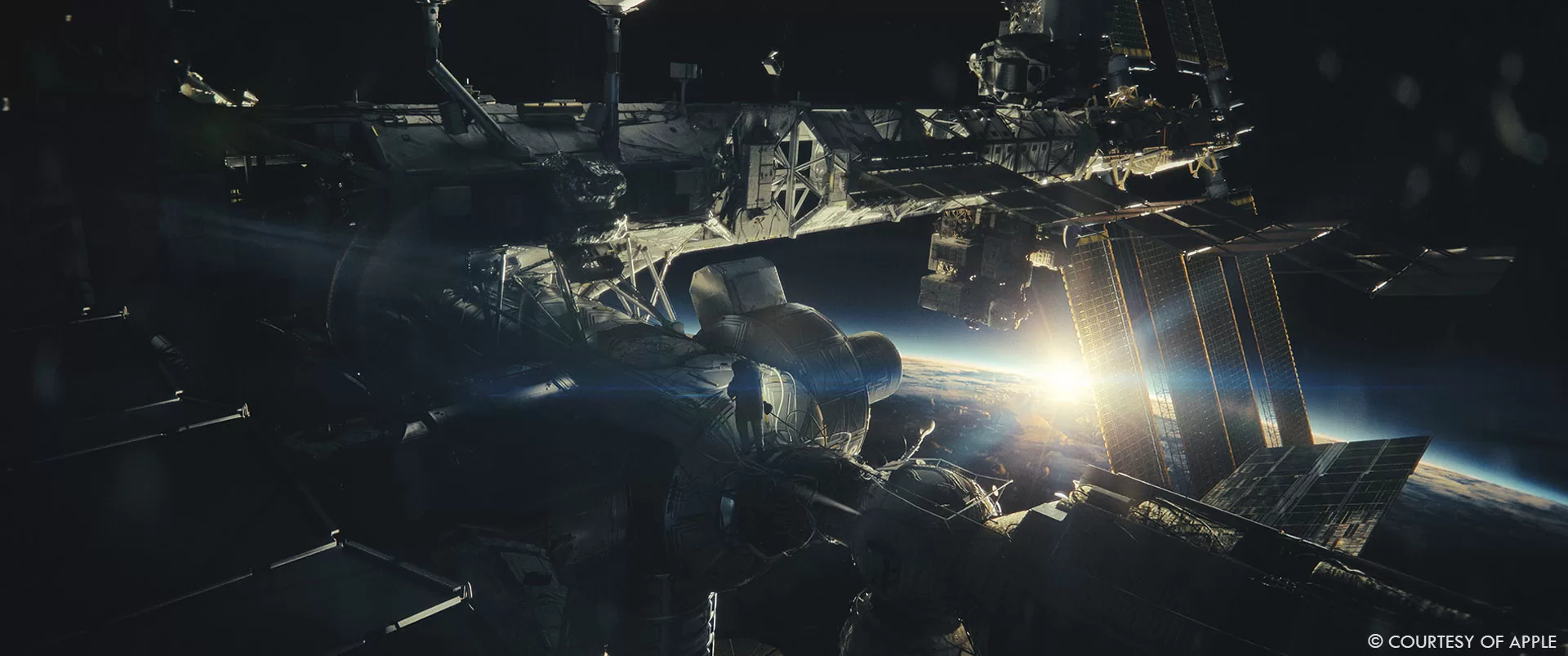

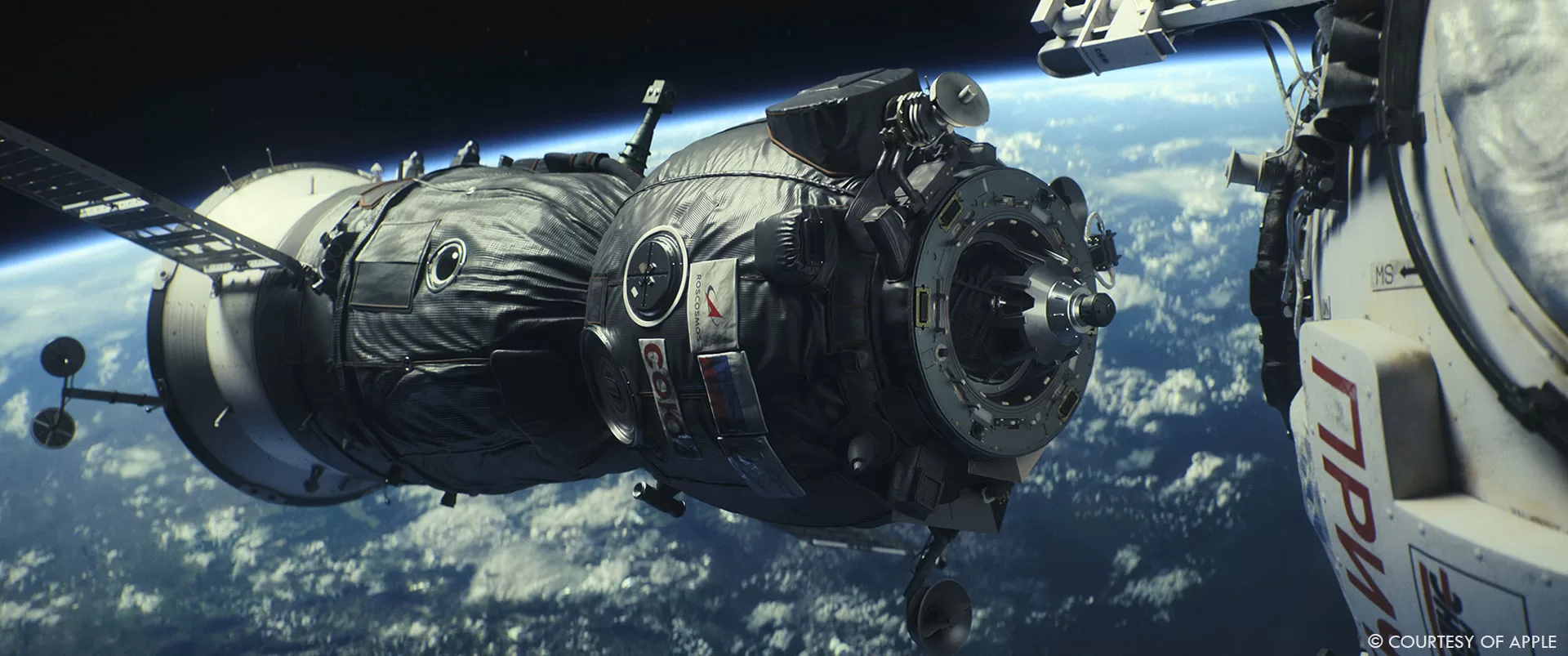

Even so, we realised that it was impracticable to build the entire ISS inside and out with the abilty to fly people on wires everywhere, and there was no where on Earth already built that would allow our director to walk through and plan her shots, Thus, one of the first things we did was to employ Third Floor to do previs on the major scenes with ourselves and Michelle which allowed her to fly around the ISS and to work out where exactly we would be staging each of our scenes on the ISS. Andy already had a 3D model of the ISS and we passed this onto Justin Summers at Third Floor; then he, Michelle and I spent a couple of months previzing/animating those scenes. At the end of it we had a blue print of where each of the scenes would be set, where the characters would travel to in zero g and when we would have wide shots vs close ups. We then made decisions on what needed to be physically built or what could be CG. In the end Andy had to build 2 sections of the russian interior and 3 sections of the American side interiors of the ISS. All these had removeable ceilings and hatchways, which could be in place for static and close up shots and removed for whenever we needed to fly people as if in zero g and replaced in CG when this was done. Andy also built 4 sections of the exterior of the ISS, the rule of thumb being that if a character touched a piece of the exterior in a mid shot then we would build that bit physically, and if you only saw it in the distance or on a wide shot then we would build it only in CG and use digi-doubles. Several of the physically built interiors and exteriors also had to stand in for alternative places every now on then with a little different dressing. Thus the Zvezda and Nauka sections of the ISS are essentially the same set.

From a VFX point of view this meant that early on in the schedule we had an idea of where we needed to concentrate our efforts, and having some of the iss built in reality, we took a wealth of photos and measurements to aid our efforts. Of course some areas were built both in CG and in reality as destructon and wires meant we had to replace various parts in VFX every now and then.

So for the most part, we extended physical sets with CG on the inside (a lot of ceilings, hatches and far bg), and we built all of the exterior in CG.

What were some of the key challenges we faced?

In many ways building the ISS was not our biggest challenge. We had set photos, measurements and a wealth of images shared freely from NASA. With enough time, patience and a lot of talented artists matching reality is standard for VFX. However, re-creating things people had never seen before is always tricky and so recreating zero g fire and blood were probably the hardest challenges we had to face in space.

How did you ensure accuracy and authenticity in portraying the ISS interiors and exteriors?

It was essential for the story that you completely believed that we were on the actual ISS. To this end, authenticity was essential from day one. As I said before, Andy Nicholson made sure that his designs were as true to life as possible, but we also had Scott Kelly as part of the advisory team on the show. Scott is a retired astronaut and spent over a year living in the ISS, and so every detail was scrutinised by him on set. We also used some of the fluid experiments he recorded on the ISS as animation reference for the floating blood scene, and we also sent Scott the completed scene for his apporoval before finalling the scene.

On top of the above, we also collated a huge library of images to use as reference both of the ISS and Earth from space. We were adamant that we didn’t want the exterior wides of the ISS to feel too CG and made sure that we had a physically shot reference photo (of which NASA have many) for every scene to match to. In this regard I’m very proud of the work that One of Us did.

Were there any unique considerations when designing the lighting for the ISS scenes to mimic the conditions of space?

I think the biggest problem with space is that photographically its a very stark and harsh light that comes from the sun, theres no diffusion except that which comes from the space station itself, and so the trick to making things realistic is to play with those very extremes of exposure that come from that environment. If you are on the space station itself and exposing for the Earth, then the lit side of the space station would peak out as its a white metal structure reflecting full sun. If however, you are on the shadow side and exposing for that shadow side of the ISS, then the Earth will be brighter than normal. To have everything perfectly exposed together would be wrong. The trick was to find lots of real world examples of space photographs and try to use them as a guide.

There was one particular shot of the Sun coming up over the horizon of Earth that we used as a testing bed. We had some real world stock footage that we had considered using until we realised that the configuration of the ISS wasn’t going to work for the story at that point, and so we copied it down to the lens flares and lens aborations that we saw. It’s a beautiful shot that goes from full black to white out!

How did you approach the integration of live-action footage with CGI to create seamless environments aboard the ISS?

As mentioned earlier, for the interiors it was mostly ceilings and hatches that were CG when everything else was practical. For these sequences we tried to make sure that we took a lot of reference photos and HDRI’s from the same camera position as we had been but with the removeable ceiling parts put back on. This allowed us a good idea of what the interior was meant to look like and made sure it would match the close ups when they put the ceiling back on.

For the exterior shots, we had a variety of shots where some would be very wide full CG, others were mid to wide with part plate and part CG, and then we had close ups which were mostly practical with a little CG bg top up. For all these shots, although we had a full CG version of the ISS exterior we tried to use as much of the practical set (which was beautiful) as we could or tie our lighting and position to the practical built set at least. For a lot of the shots the wire rig or fork rig that the actor was on partially obstructed the set. For some shots this meant just painting out the offending rig, but for others it meant partially replacing the practical set.

All the way through the main exterior sequences we had The Third Floor’s previz of these sequences which we used as a shooting guide so it meant that, for the most part, we got the plate that we had hoped for and planned for. This made post a lot more straight forward than it could have been and a lot less expensive than if we had given everyone free reign without prior forethought.

In terms of scale and detail, how closely did you match the real-life ISS in your visual depiction?

Our ISS is a little like the tardis in that its slightly bigger on the inside than it is on the outside. We tried to match the scale of the ISS perfectly on the outside, but on the inside the real-life ISS is slightly more cramped, which doesn’t make for a very practical set, and so its about 10-15% bigger on the inside to allow for wire rigs and camera crew. In terms of VFX, we matched to the practical sets as we had to line everything up to the plates that were shot. To be fair to the vendors, we hadn’t told them this until we got some rather confused matchmove artists who were trying to line up a real-world model of the ISS to the plates and Lidar scans that we had sent them.

In terms of detail, our ISS is a little less cluttered on the inside. If you go to the Nasa homepage you can take a virtual tour of the ISS. In that you will see an awful lot of air conditioning hoses, stored experiments and parts ready to be fitted cluttering up various parts of the interior. We didn’t add so many of these to make for an easier passage of characters and crew. Other than that though, Andy Nicholson and the set dec team (under Mark Rosinski) and the prop team (under Moritz Heinlin) did a fantastic job of making the sets as true to life as possible and we matched this with the extensions we did and with the digital props we added to that.

Once again we also had Scott Kelly with us and so he added a few nice touches to the set dec, like the constant use of duct tape to fix things. The ISS has been in space for a long time, with quite a few repairs and additions done by the astronauts who visit and apparently they use duct tape to fix everything apart from holes in the structure for which wet wipes can be used as they freeze and expand when they come into contact with the freezing temperature of space. Who knew?

Were there any particular scenes or sequences set within the ISS that posed significant technical or creative challenges?

I think that the zero g fire had to be the most technically difficult challenge. Everyone knows what fire looks like but no-one knows how zero-g fire reacts. There are very few examples of where fire has been experimented with in zero-g so theres very little real-world reference to look at. The general concensus amongst physicists is that the very narrow fingerlike form of fire (that you see in a candle for instance) is created because of heat rising against the pull of gravity which works in a very linear way on Earth. And so in zero-g the radiation of the fire would work in an omindirectional fashion making for a fatter and more rounded appearance of the flame. You can’t make this happen on Earth, so you can’t do practical elements and so it had to be CG fire, but how do you make CG fire look like real zero g fire (which doesn’t react like normal fire) and not just bad CG fire. That was the challenge.

After lots of experimentation with Victor Tomi and his team at One of Us we decided to try and base our zero g fire on 2 types of Earth bound fire that don’t look normal, but also don’t look wrong. The first was ceiling fire. When fire can’t go up and is stuck against the ceiling it flows in a more rounded and cellular fashion. We looked at lots of examples of this and designed a simulation that would act like this no matter where it was. So this simulation combined with a fatter traditional fire simulation that flickered out (even when it was positioned upside down) were used whenever we had fire on something.

The other odd fire is gaseous fireballs. When you shoot one of these from above it appears round and not to be effected by gravity as it is expanding in all directions equally. So whenever fire was moving towards us it acted like a fireball and thus not gravity bound. The final touch were embers which flowed in every direction and tied everything together.

How did you approach shooting Zero G sequences and what techniques did you employ to achieve a convincing sense of weightlessness?

There were several ways that we tried to acheive that sense of weightlessness. The most obvious was through flying people on wires. Here I have to tip my hat to our stunt and special effects supervisor, Martin Goeres. On seeing how many sets we would have to fly the actors through he built Europe’s largest motor controlled track system. It could fly a performer over an area of 1000m2 in all directions. It was motion control capable as it had computer controlled winches. So at all times and on all sets we were able to fly 2 performers anywhere which allowed for physically appearing zero g actors. The task was then down to us to remove those wires in post and deform their costumes where you could see the harness showing through as well as replace the ceilings where the wires came through.

The second way to create the idea of weightlessness was through the abundant use of floating CG objects. One of us created floating bags, torches, screwdrives, nuts, IV bags, batteries, fire extinguishers, hoses, spanners, tempeature guages, drinks bags and of course blood. Rather amusingly/annoyingly whenever we shot any scene we had a box of objects that we would get lighting reference of along with our chrome ball. I’m sure the first AD’s loved the 2 minutes it took to do our dance of floating objects before we were able to move on.

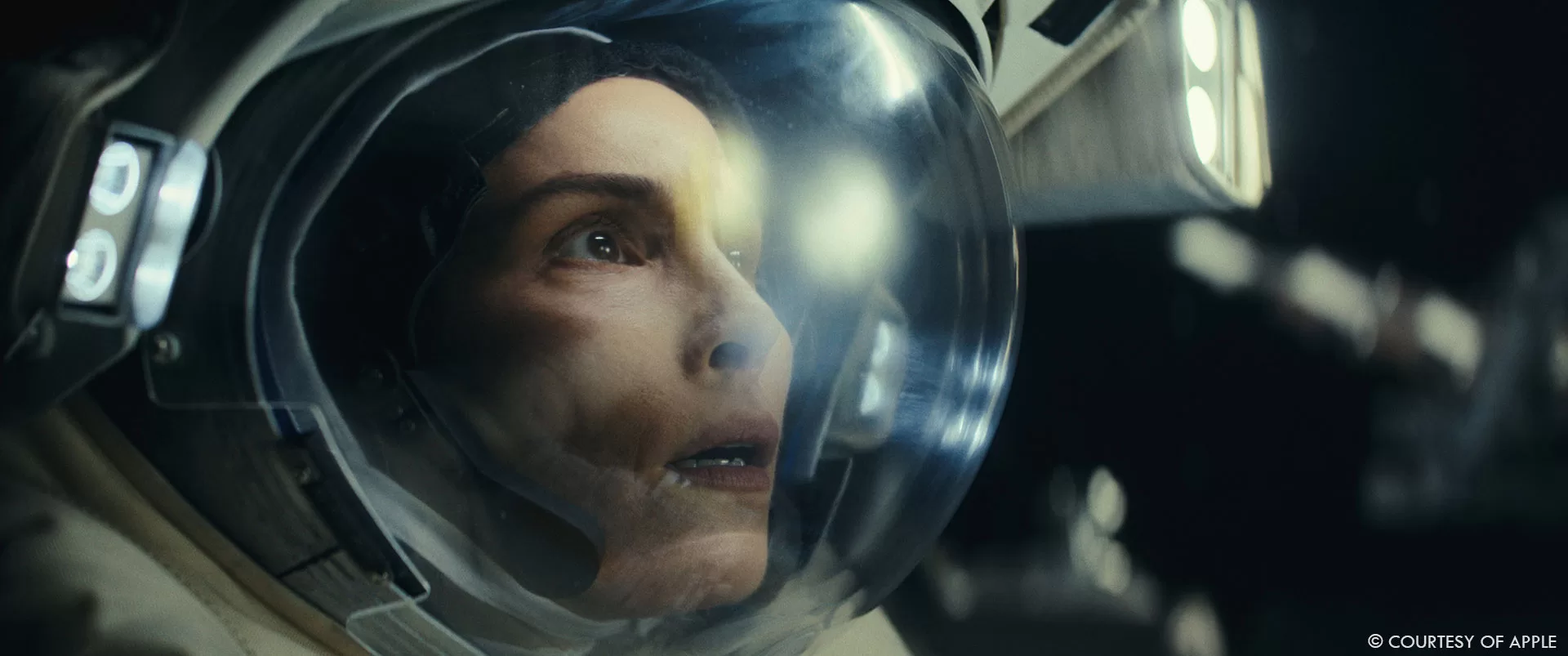

Thirdly, it takes a lot of effort by the actors to act as if they are weightless. I have to pay tribute to Noomi and the other astronauts who paid great attention to moving slowly and gracefully. A lot of shots didn’t have to be done on wires because they acted so well on one leg.

Finally, we realised early on that the camera itself needed to have more float than usual in order for it to feel weightless. After seeing this happen on set, we copied this with our full CG shots later.

Can you walk us through the post-production process for the zero G sequences?

From a post-production standpoint, it started with the edit. You would see the latest edit and then chat to the director and editor about what that meant from a VFX point of view; whether the number of shots where wires, CG extension and CG props that were needed fell within the budget allowed for each scene. Then, from there we would highlight with the director, which shots needed a CG prop and what it should do. And then we’d discuss any particularly problematic shot for us. For instance, if the editor had chosen to use a shot where one character and their 8 wires had crossed right in front of the face of another actor, then we would be able to request if a different shot could be used as wires crossing faces are notoriously difficult to paint out convincingly. To their credit both Michelle MacLaren and Joseph Cedar were very understanding of this type of thing and we had very few issues like this.

From there we briefed One of Us or Studio 51 (who did a lot of stand alone wire removals) about what was needed and we would plan to see an animation playblast to confirm with Michelle or Joseph whether we were on the right track in regards to animation, scale and movement of extensions or props. From very early in the edit process (before we locked) we had picked out key shots where build and look development could start on a number of the sections of the iss and the key props, and so by the time we locked the cut, much later, the process of moving from animation to final lighting render was quicker. Michelle and Joseph were very much involved in the review process and would regularly drop updates of our work into the edit as there was so much VFX in the edit. It was a big day when we no longer had any greenscreen or previz still evident in the edit of episodes 1,2 and 6. Having said that we were still designing some stand alone space shots only weeks before delivery. It is testament to Victor and his team at ‘One of Us’ that no stone was left unturned in the fight to deliver some spectacular VFX.

Can you ellaborate about the impressive destruction sequence inside and outside the ISS?

I suppose the question I have for you there is « the destruction in which reality? » I think keeping track of which Jo is in which part of the ISS at which point and in which reality was actually one of the toughest things about that whole sequence.

From a VFX point of view, other than the CG fire and CG blood the most elaborate shot is when Jo dies in episode 6 where we got to do a digi double take over, followed by a some gruesome gore getting sucked out of the cupola window. The original idea for the shot was that we would do a stunt in reverse where Noomi starts at the window and is pulled back on a wire. The idea being that when you played this backwards it would look like her falling and hitting the window, but this didn’t quite work out as it never felt like she hit the window with enough force. Thus, we decided to do a digi double of noomi falling towards the window and then invisibly cutting to a plate of Noomi with her all bloodied up and some CG goo getting sucked out of the window. There was a lot at stake as its a major story point in the series and so we spent a long time making sure the animation of her hitting the window felt like it was realistic and brutal enough. We also had to make sure that the reprojection of Noomi’s face onto the digi-double brought enough detail and realism so you didn’t notice the takeover.

Can you tell us more about the challenges and techniques involved in creating the destruction sequence?

This was one of the major sequences that we prevized early on with The Third Floor and it was well worth it as it was such a complex sequence to navigate as it appears more than once in more than one reality. Some moments are shared and some are completely different. Without having prevized the sequence I doubt we would have shot it all correctly. We used this previz as a shooting guide and ticked the shots off as we went rather than necesarily shooting a whole sequence from several angles arbitrarily and getting ‘coverage’ as is often the norm. This certainly saved time. Having the previz also allowed us to show the actors what was going on and allowed them to see the CG props that were flying towards them and so they could change their performance to allow for the VFX.

Once in the edit, we then tailored the previz cut to make best use of the plates we had, often adding in speed changes or digital zooms to make the scene more hectic and disorienting. Only then did we start animating all the CG that went into it (fire, flying objects, blood, fire extinguishers, bags, shards, etc). However, because we had the previz and the creative team had all bought into the previz, we were already clued in to what objects went where and how they moved. It was an incredibly complex jigsaw but I’m very proud of it.

The series portrays scenes set in Kazakhstan and Sweden. Could you elaborate on the process of creating these diverse environments through visual efects?

Let’s take them one at a time. When we first talked about shooting Constellation we had thought we might actually go to Kazakhstan and shoot at the real Baikonur, then Russia invaded Ukraine and that idea was most definitely out. So we had to come up with how we would recreate Baikonur. The production decided we could get similar landscapes in Morocco and so it was decided we would shoot there. We found a great airport in Errachidia that could stand in for Baikonur and VFX would add Baikonur town with all its launch facilities in the distance. We also found a great landing site on the Kik Plateau, with the Atlas mountains behind, and there we would add a CG capsul landing and a host of CG helicopters rushing to the rescue. However, we didn’t find a good stand in for mission control and so it was decided we would use Templehof Airport as an exterior location and then VFX would transplant it into the Morocco desert. Not an easy ask, especially when you have to try and match lighting between a blistering hot day in Morocco with November weather in Berlin. Outpost took on all this work and did an outstanding job.

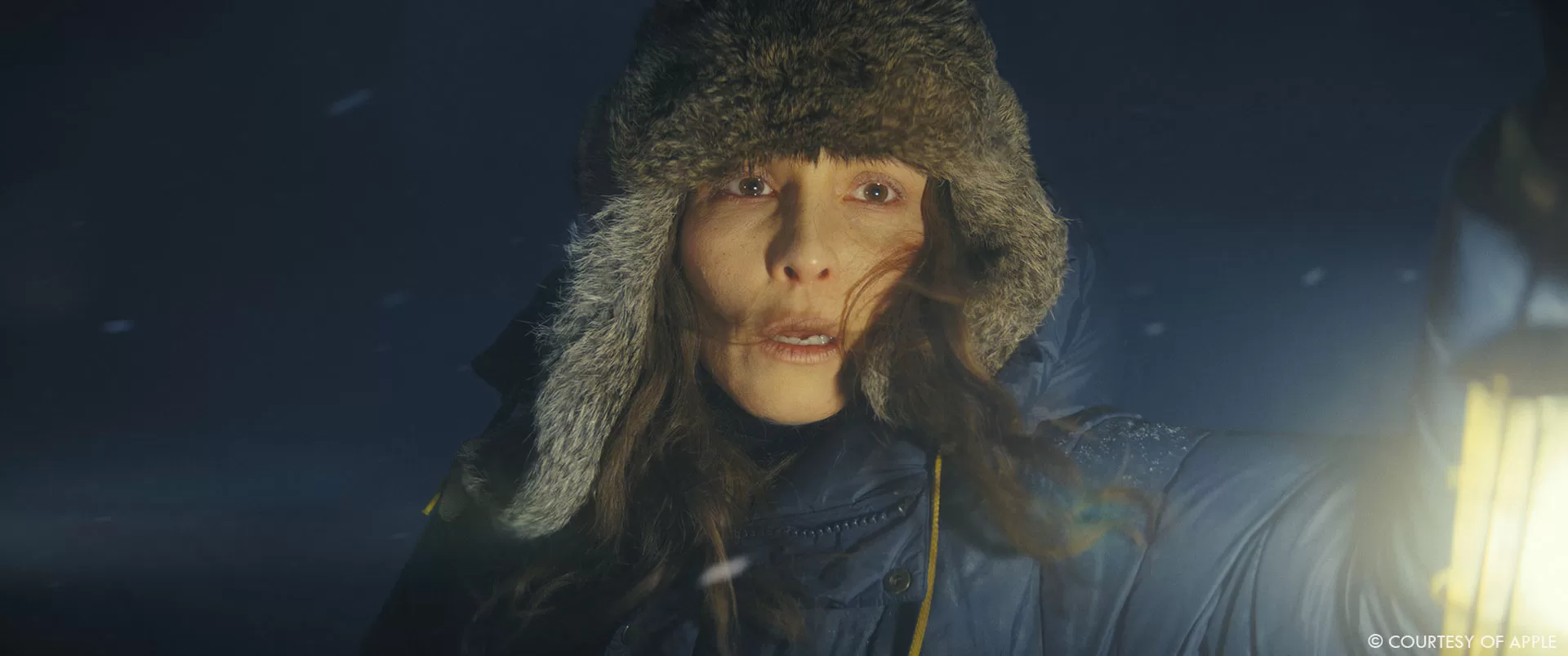

Then we have Sweden, or actually Finland in the end. The snow was actually one of my biggest concerns when I first read the scripts. There was an awful lot of scenes set in a snowy and misty landcape and having recreated snow before its often overlooked as an easy thing, but in this case we had a frozen lake with big vistas of a snowy landscape and a snow/fog storm that seemed to have its own character and so I was keen that we didn’t underestimate its importance. One original idea was that we might set the lake somewhere in Germany and recreate the first 50m of snow and then need VFX to recreate verything else, but the sheer volume of shots that this would need VFX to do major top ups on made this cost prohibitive. In the end we decide to shoot on a real frozen lake in the arctic circle in January. We still needed to add snow and fog to almost every shot as the weather was very changeable, but it made for some absolutely stunning shots of which Jellyfish can be extremely proud.

Can you discuss any specific challenges or highlights in the visual effects work for Kazakhstan and sweden environments, particularly in terms of integrating CGI elements with live-action footage to establish a sense of place and atmosphere?

As mentioned before, transplanting Templehof in Berlin into the desert was a big challenge for Alex Grau and the team at Outpost. We knew when we went to Morocco that this would be happening later and that we would need to shoot some establishing shots in Morocco where we could sit a CG version of Templehof into. We also needed to shoot vistas that could go into the BG of the shots taken in Berlin. This made for a fun few days spent with the drone team flying around the desert and taking lots of lovely establishing shots. What we didn’t quite realise then was the scope that we would use these establishers and how much of Templehof and the launch sites we’d have to build in CG. When we first quoted on these types of shots we thought we might take a 2.5D approach to what you see added to these desert vistas, but after cutting these establishers in and talking it through with Michelle we realised that we would have to fly right over a CG version of templehof and the launch sites. To this end the level of detail needed for these builds was ramped up and so by the time we came to shoot templehof we made sure we took lots of drone footage of the airport building and a myriad of texture photos and Lidar scans to feed into the CG build. The final sequences have the feel of a Bond Movie as we fly between the radar dishes and land in Baikonur.

Could you elaborate on the process of adding snow to certain environments?

There was an awful lot of snow in Constellation. We shot in an absolutely stunning location near Inari in northern Finland. We were so far North that even Santa lived south of us. This meant we had guaranteed snow on the ground and a frozen lake we could physically drive on. In some ways we had too much snow, as the lake didn’t look like a lake but more like a vast snowy field. To this end for some of the establishers we had to project patches of ice texture onto the lake to make it appear more like a frozen lake. The biggest challenge though was the snow and fog. The script called for the fog and snow to come and go at very specific points and to act almost like a character of its own. So we knew that this wouldn’t just be a matter of adding some simple fx passes over some plates, but a very art directed snow and fog that didn’t take over the shots and distract from some very moving moments but added an underlying texture and intensity to the scenes. We turned to Jelly fish to help out here. They had done some similar work on Stranger Things and we knew the team there very well from previous shows and so we knew we could trust them to pull off such a nuanced brief.

On set the SFX crew helped set the tone with some physical snow and fog, but it is impossible to fill an entire lake with fog and snow, or for them to cover every type of shot. We also had more than one unit working a lot of the time and so SFX couldn’t cover every moment when snow and fog were needed. This is where Ingo Putze and his team came to the fore. We shot some snow elements for them , but they created a lot of snow sims. They treated each snow shot individually and with the attention it deserved to create the perfect level of snow and fog for the reality and emotional tension that was needed. They also had to deal with multiple lighting set ups. We shot some shots in full sun and some in almost darkness, but they were meant to be the same moment. They dealt with this marvellously and with calm aplomb.

On top of the above, Jellyfish did a great service to the show, in that they were able to turn around some very demanding 360 Stitch shots that were needed to shoot the car interiors on a video wall 3 weeks after we shot the footage in Finland.

Were there any memorable moments or scenes from the series that you found particularly rewarding or challenging to work on from a visual effects standpoint?

I think the shot I was most looking forward to doing was Bud (Jonathan Banks) throwing Ian Rogers (Shawn Dingwell) off of a cruise ship. From very early on in the script this stood out as a shock moment in the story and it was important that we got it right. It had to feel really believable and dark. We also decided fairly early on to do part of it as a practical stunt on the ship, which I think helps sell the wide digi double shot that Mathematic completed for us. Sebastien Eyherabide, Martin Tepreau and Fabrice Lagayette at Mathematic were fantastically patient with us as we tweaked the animation of this shot in particular down to the nth degree. I can’t thank them enough.

Looking back on the project, what aspects of the visual effects are you most proud of?

I am very proud of all the work that we did. There are a lot of in your face big visual effects, like the ISS or the re-entry scenes, but theres an awful lot of more subtle work, like adding breath to the characters when they first come into the cabin which was shot in the middle of a heatwave in Cologne. And I’m just as proud of that too. Our vendors did a fantastic job. Overall, I’m just happy that we got through everything we needed to and it all looked good.

Tricky question, what is your favourite shot or sequence?

You’re right, that’s too tricky a question. Space, Earth, the ISS, space Fire, zero g flying objects, fire extinguishers, Blood, Parachutes, Wolves, helicopters, launch sites, mission control, hundreds of screen inserts, thousands of wires, dead cosmonauts, frozen wastelands, the CAL, fog banks, cabin fire and breath. They are all loved.

How long have you worked on the show?

Just over 2 years from first script read to final shot delivered.

What’s the VFX shot count?

1582 shots.

What is your next project?

I am enjoying a break, it seems a little quieter than normal at this time, but I’m open to offers.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

- Jaws

- The original Star Wars Trilogy

- North by NorthWest

- and All the James Bond Movies

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

One of Us: Dedicated page about Constellation on One of Us website.

Outpost VFX: Dedicated page about Constellation on Outpost VFX website.

Jellyfish Pictures: Dedicated page about Constellation on Jellyfish Pictures website.

Apple TV+: You can watch Constellation on Apple TV+ now.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2024