Alex Wuttke has worked at Jim Henson’s Creature Shop before joining Double Negative in 2002. He worked on films such as THE CHRONICLES OF RIDDICK or BATMAN BEGINS. As a VFX supervisor he took care of the effects for movies like QUANTUM OF SOLACE, 2012 and 2 THOR: THE DARK WORLD.

What is your background?

Before entering the world of visual effects, I worked as a graphic designer. I managed to persuade the company I was working for at the time to invest in the area of 3D, stating that advanced computer graphics could open up a new world of illustrative and graphic options for the design work we were doing. Having done the sales pitch I found myself self learning Alias Power Animator on an SGI, producing visuals to incorporate into our design work. One thing led to another and I ended up joining Jim Henson’s Creature Shop in Camden Town, learning my trade as a junior TD and working my way up until joining DNeg in around 2002.

How did you and Double Negative get involved in this show?

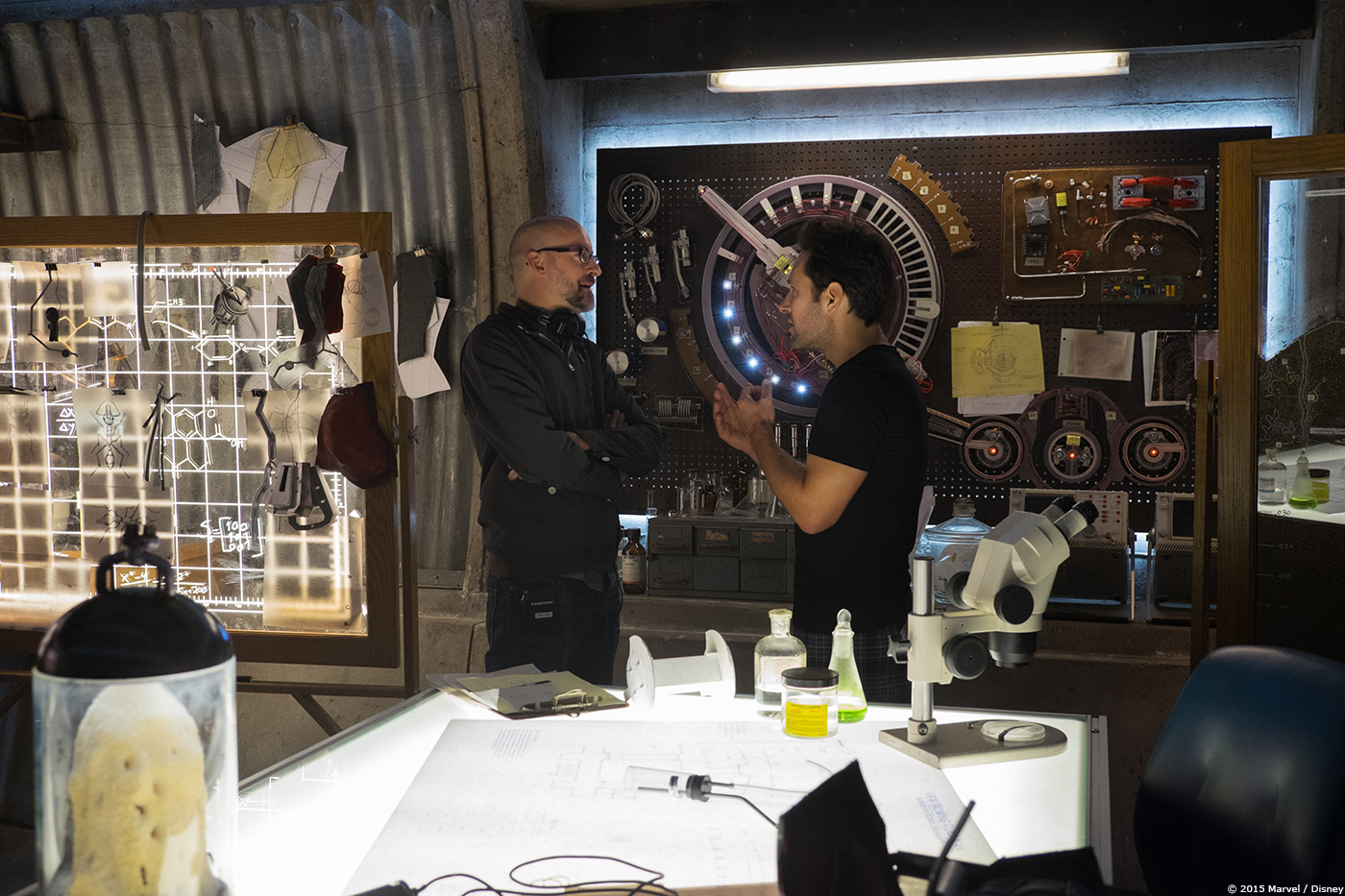

We had been involved in Ant-Man in one shape or another for many years. We have close ties with Edgar Wright who had been developing the film for a long time, and ultimately produced a proof of concept test which ended up at Comicon in 2012. This was supervised by Frazer Churchill, one of our visual effects supervisors. A lot of the visual mechanisms from that ended up informing what would come later. I came onto the project at around the same time as Jake Morrison, since we had just finished working together on THOR: THE DARK WORLD, so the scheduling of things was fortuitous. We immediately started discussing how we would approach the work, with discussions largely circling around how we would realise ANT-MAN’s macro environments.

How was the collaboration with director Peyton Reed?

Peyton was a joy to work with. He’s very savvy when it comes to visual effects and understood the challenges we faced. When it came to the work, he knew exactly what he wanted, which always helps, especially with a very compressed schedule.

What was his approach about the visual effects?

From a very early stage, everyone was adamant that we wouldn’t go with oversize sets or props when we were down at Ant-Man’s scale. Peyton wanted to see a real world at the macro scale, along with all of the natural grit and grime you’d expect viewing the world from Ant-Man’s perspective. He was keen for us to create environments that would speak to the real world and to embrace the kinds of natural chaos and surprise in detail you can only really get with macro photography. This would become Ant-Man’s world.

How was the collaboration with Production VFX Supervisor Jake Morrison?

Jake is a great guy to work with and has a fantastic eye. We had worked together previously on THOR, so there was a shorthand there by the time we picked things up for ANT-MAN. A lot of the techniques we developed on that show in terms of lens mechanics and photographic realism were expanded upon for ANT-MAN. Because of his love for all things optical, and due to the nature of the work, we had an amazing opportunity to really dig in to some of these aspects of the work and push them much harder than we would otherwise have had the luxury of on another kind of show.

What was the work done by Double Negative?

We came on early and developed the onset capture methodology for the macro environments, with a view to distributing « solved » data sets to other vendors as well as for our own sequences. We were also charged with developing the hero Ant-Man and YellowJacket digidoubles for use in our work and for distribution to other facilities. In terms of actual sequences, we worked on the First Suit Experience, when Scott first shrinks in Luis’s bathtub and makes a perilous journey down through the apartment building, Scott’s First Flight sequence, in which Scott rides on the back of a winged ant through the streets of San Francisco, the Helicopter Fight sequence, in which Ant-Man battles YellowJacket inside a helicopter and ultimately a briefcase, and the Final Little Fight sequence set in Cassie’s bedroom.

Can you describe one of your typical day during the shooting and the post?

During the shoot, at Pinewood studios in Atlanta, I was embedded within the macro unit, and supervised the stills macro photography. Jann Engel, the macro unit art director, had assembled a series of tabletop sets; Full size partial pieces of set which we would then need to capture in order to generate our environments in post. Using the methodologies formulated during prep, we photographed these with custom macro stills rigs. The three rigs comprised of Canon 5D mk3 bodies fitted with 100mm macro lenses mounted on Rodeon robotic pan and scan heads, all feeding into a Dneg workstation for stitching and storage. These rigs allowed us to photograph the sets with incredible clarity of detail at the macro level, the kinds of detail that Scott would see at his diminished size. As well as photographing the sets, we also recorded their geometry, using a combination of lidar and structured light scanners. Due to the high volume of sets and the time intensive nature of this process, and due to the fact that we would be dove tailing into the motion picture photography happening on the macro stage, planning and scheduling were everything.

Back in London for post, my days would be divided up into early morning calls with our office in Singapore, who were handling some of the work, dailies through the rest of the morning and afternoon to review shots, and then client calls with Jake in LA in the evening.

How did you approach this new Marvel show?

A key tenet of this production was to make things photoreal. With the digidoubles, this is something we had plenty of experience in prior to the show, so a roadmap was already in place. For the environment and FX work however, we had to invent new processes and approaches. From Ant-Man’s perspective, the world is full of incredibly rich detail, most of which you would never normally see, but would be conspicuous in its absence. This informed the approach to the work and ultimately drove the creation of the macro unit, so that we would have a rich record of actual macro detailing of real world surfaces with which we could build ANT-MAN’s world. We also invested in The Foundry’s Katana, which we used to assemble the complex and disparate environments along with the digidoubles.

Can you explain the details about the creation of Ant-Man and YellowJacket?

We knew early on that Ant-Man and YellowJacket would be largely CG whenever you saw them, more so with YellowJacket since the costume department never actually built a costume for Corey Stoll.

For the Ant-Man suit, we took our PhotoBooth rig to Atlanta and captured Paul Rudd in costume. Our rig comprises of an array of digital SLR’s shutter synced to a series of polarised and unpolarised studio flashes, which we use to generate high resolution meshes via some in-house photogrammetry solvers, but also registered, cross polarised textures for the subject, from which we can extract diffuse albedo, specular and displacement detail. We also had a smaller rig for scans of Paul’s facial expressions. Armed with this data, we then generated high res models for the various parts of the suit along with corresponding texture maps for the various shader channels. We used an early cut of Prman 19 for all of our work, so ldev happened within Katana, using our in-house shaders built around that, although we did prepare a broken down package of models and textures, as well as stub shading graphs for distribution to other facilities who would also use our Ant-Man asset within their shots. During ldev, we rendered a side by side comparison with some live action footage of Ant-Man in full costume as a ground truth prior to sign off.

YellowJacket, due to the absence of a practical suit to match to, involved a fair amount of design work to come up with the final look. We went through several iterations of materials and detailing prior to sign off, studying various high tech materials, so that the YellowJacket suit would have a recognisably more modern feel to it than the Ant-Man suit, which was decidedly vintage in appearance. We studied things like ballistic nylon, kevlar and vulcanised rubbers as a starting point. The yellow paneling however had to be unique and couldn’t be based on a pre-existing material, so we came up with a series of shader functions to describe the way that light would react to it. The end result used inverse fresnel functions with some retroreflective components, with the overall effect helping to give YellowJacket a strong and easily readable silhouette. We tested the ldev in a live shot to get final sign-off.

The additional complication was that both Paul and Corey’s partial facial performances would need to be visible within their masks, so we would need a way of recording these performances and drop them in to shots. We came up with a methodology in which we would have Peyton direct Paul and then Corey through various expressions and performances whilst they were surrounded by an array of Alexa cameras, recording their performances from various angles. We also markered their faces for facial tracking and shot them in flat light. This gave us a library of performances and expressions which we could project onto their facial rigs inside their helmets, using lookups into the array depending on their relationships to the shot camera.

How did you handle their rigging and animation?

Rigging for both characters was handled using our in-house developed modular rigs. The challenges for Ant-Man revolved around the fact that his suit is relatively loose fitting leather, so we had a cloth step for each shot featuring him, to get the right feel to the creasing and folds in his suit based on his shot performance. YellowJacket had a pair of mechanical arms with plasma canons, dubbed stingers, which had a semi autonomous aspect to them. They reacted in a similar way to a steadicam rig, in that the muzzles would need to stay locked on to a target whilst connected to YellowJacket, who would be in motion. For animation, we used a base layer of mocap, and then keyframe animated over the top.

Can you tell us more about the shading and textures?

At Dneg, we use a variety of renderers for different things, but try and maintain a single code base for our shaders. We use OSL to port our shader code between the various renderers, and developed a set of these shaders to plug into Prman 19 and Katana. Due to the nature of light transport at a macro scale, using a bi-directional path tracer was important to us, and keeping lighting sources at a physically accurate scale helped with selling the look of a tiny character. For instance, when Ant-Man is very small and standing next to a regular sized lightbulb, the light source would act in a similar way to a stadium light, with light wrapping around Ant-Man. Because his suit is relatively reflective, this light would also bounce off his suit and back in to the environment. All this needs to happen with the correct energy preservation for it to appear real. This effect was most obvious during the briefcase fight. There’s only one light source in there, which is the light given off by the iPhone lock screen, so the majority of the work in lighting characters is done through bounced light.

For texture maps, we use UDIMs, and paint and project in Mari. For projected environments, we preserve the full linear exr all the way into the comp, but for RGB textures, we bounce down to 8bit tiffs.

How did you created the various environments?

For the environments, we would harvest textural information from our work in the macro unit. The photographic process revolved around shooting tile sets of the macro sets on 100mm macro lenses from multiple vantage points. The problem with macro photography is that there is an inherently shallow depth of field. Our process involved the use of focus bracketing to give us an infinitely sharp tile. For each shooting position over the set, we would shoot multiple panoramic tiles, with each tile consisting of multiple focus brackets, and each focus bracket consisting of multiple exposures to accurately capture the dynamic range of the surface. By way of example, a single panorama covering 1ft of set would consist of around 18 tiles, each comprising 15 focus brackets, with each bracket containing 3 exposure brackets. We would then combine each exposure bracket into a high dynamic range exr. We then performed a frequency analysis across the focus bracketed exrs to produce the focus stitched tile, and then perform a feature analysis to stitch each tile into a continuously sharp panorama. Shooting from multiple positions allowed us to cover areas of occlusion across a projection. Because we had three rigs shooting in parallel, we could cover the entirety of a macro set from any conceivable angle and drop our virtual camera into any position. Most of our environments were built this way, with these projections forming the base coat on top of recovered geometry. We then added specular detail and displacement from recovered data out of the photography. We would add additional dressing to each environment in the form of dust bunnies, dust drifts and general atmos with Houdini volumes rendered in Mantra. The goal was to faithfully recreate each photographic environment from a novel viewpoint, preserving the macro detail which would act as the hallmark for the world inhabited by Ant-Man.

What was the most complicated environment to create and why?

Cassie’s bedroom offered the biggest challenge, due to its size and complexity. Whereas most other macro sets were contained one-offs, we knew that the Final Little Fight sequence would take in almost the entirety of Cassie’s bedroom, which was a very cluttered and rich environment. We ended up shooting in the actual set for over a week, harvesting as much detail as we could in the time available. As well as shooting everything in the room in situ, we took each of the toys and props within the room and shot cross polarised macro reflectance data in a blackout tent so that we could recreate each object faithfully in CG. Ultimately, we harvested a huge amount of data from that set and pieced everything together in a multi tiered way. The distant BGs in that sequence were HDR photo bubbles of the room projected onto lidar data, the MGs were from our macro panoramas projected onto structured light scans, and the close up props, such as Thomas, were full CG props, with textures recovered from the reflectance photography.

How did you design the shrinking FX?

In our early proof of concept tests with Edgar, the basis for the shrinking effect was established. The idea was that as Ant-Man shrinks, he would leave time echoes of his silhouette in space behind him, which would take on a silvery refractive outline. The effect stayed with us pretty much all the way into final shots in the movie, since everyone fell in love with it. We dubbed it the Disco Shrink effect.

Can you tell us more about the various FX elements such as water and laser?

Early on in prep and then during the shoot, we shot as much macro reference of various natural phenomena as possible, so that we could see how water would move when seen at the macro scale. We would shoot passes using a Phantom Flex 4k high speed camera at 1000fps. What we found was that from this perspective, things evolve in very interesting ways. At the macro scale, water moves with a lot of surface tension, so this was something we built in to our simulations. Explosions and pyro also have their own kind of surface tension at this scale, so we spent a lot time developing the look of macro flames via simulations to incorporate into pyro events when we’re down at Ant-Man’s scale.

How did you approach and created the final battle and especially around the miniature train?

The whole final battle ended up being fully CG, with fully CG environments, vehicles and characters. As mentioned, we spent a lot of time harvesting data from the full size Cassie’s bedroom set designed by Shepherd the production designer, and lit by DP Russell Carpenter. This included shooting accurate HDRIs, so that our characters and CG props could be properly integrated into the projected environments. Some aspects of the set were hard to recreate with straight projections, such as the carpets, so we used fur systems for these, with base textures extracted from the photography.

The character action was derived from mocap performance of Corey and Paul captured during the shoot, with keyframe animation layered on top. We also added subtle details like rattle to Thomas and his carriages, which would transmit into the character performances, making Ant-Man and YellowJacket perform subtle weight shifts to stay balanced. During the macro unit shooting schedule, we also had SFX supervisor Dan Sudic rig some toys up with tiny charges, which we shot on high speed Phantom cameras fitted with Frazier lenses, to see how these props would break apart at a macro scale in slow motion. We would then use this footage in FX to recreate the way that toys would break up and how the pyro would look from Ant-Man and YellowJacket’s perspectives. On top of all of this, we added FX motes and particulate into the air to lend things a soupy macro feel. In comp, we created various optical effects to help sell the macro photography look, including an optically correct bokeh effect for our defocus driven by deep data and using measured circle of confusion kernels. We knew that defocus would be super important to the macro look, so invested a lot of time in ensuring that our defocus reacted appropriately to the virtual lens we were shooting with. This took into account factors such as barn doors on the camera for flare control, as well as things like heat haze from macro flames, which would subtly alter the defocus in depth. On top of this, we added physically correct lens breathing during focus and zoom pulls, as well as animated iris manipulation.

What was the main challenge with him and how did you achieve it?

Thomas featured very heavily in the final battle, and is featured up close in huge detail through most of it. We spent a lot of time in surfacing Thomas, adding subtle imperfections such as plastic injection moulding errors, overprinting errors and greasy smudges from fingerprints. All of these added to a photorealistic looking Thomas the Tank Engine.

Was there a shot or sequence that prevented you from sleep?

The shot in the bathtub where the tsunami of water chases and envelopes Ant-Man were the most nerve wracking, due to their complexity. The sims for the shot featuring Ant-Man running away from the torrent of water were incredibly heavy, with the sim for that one shot taking up over 81 terabytes of storage, and due to the refractive and transmissive nature of water in a bright white tub, took over a week to render on our render farm!

What do you keep from this experience?

The whole venture, from prep through to final shots was incredibly fun. The work was challenging but hugely rewarding and the end results are beautiful.

How long have you worked on this show?

Personally, I’ve been involved in the project for around a year and a half.

What is your next project?

Summer holidays with the family!

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER and ALIEN, Lynch’s DUNE, Truffaut’s THE 400 BLOWS.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Double Negative: Dedicated page about ANT-MAN on Double Negative website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2015