In 2012, Raymond Chen explained the work of Rhythm & Hues on CHRONICLE. He then worked on WINTER’S TALE and then INTO THE STORM. In 2016, he joined DNEG and took care of the effects of films like STAR TREK BEYOND and THE MEG.

How was the collaboration with VFX Supervisor Eric Saindon and the Weta Digital team?

DNEG had a number of shared shots with Weta Digital. We also were tasked with completing a number of cyborg assets that had been started by Weta, so there were a few meetings at the start to ensure our pipelines would work well together. We had to work out how to share cameras, rendered elements, lighting information, as well as animated geometry, since some of our shared work was highly integrated.

Mike Perry, Weta’s CG supervisor, and Russell Bowen, DNEG’s CG supervisor, spent a fair amount of time making sure the technical side was solid, so that once we got deeper into production we were mostly focused on creative issues, and able to interact more with Richard Hollander and Jon Landau, rather than the Weta team.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

We had a lot of work shared with other facilities, so we needed to work out concrete schedules for delivering and receiving assets and elements in order to meet deadlines. Internally, we tried to organize the work into shot groups of similar types of VFX work, and to formalize a notion of shot stages for accurate tracking of progress of shots.

How was the work split amongst the DNEG facilities?

Both our Mumbai and Vancouver studios worked on all stages, from build through to animation, lighting and comp. We tried to keep the work for specific sequences concentrated within one location. For example, Mumbai was the primary facility for the street Motorball pickup game, while Vancouver handled the bulk of the work in the Ido daughter flashback sequence. Both facilities had groups of shots from the bar fight sequence, which needed closer coordination to keep the shots consistent.

What are the sequences made by DNEG?

DNEG worked on the bar fight sequence, pickup street Motorball sequence, a Motorball locker room sequence, the Amok cyborg / Ido daughter flashback sequence, and well as smaller groups of shots in a number of other sequences.

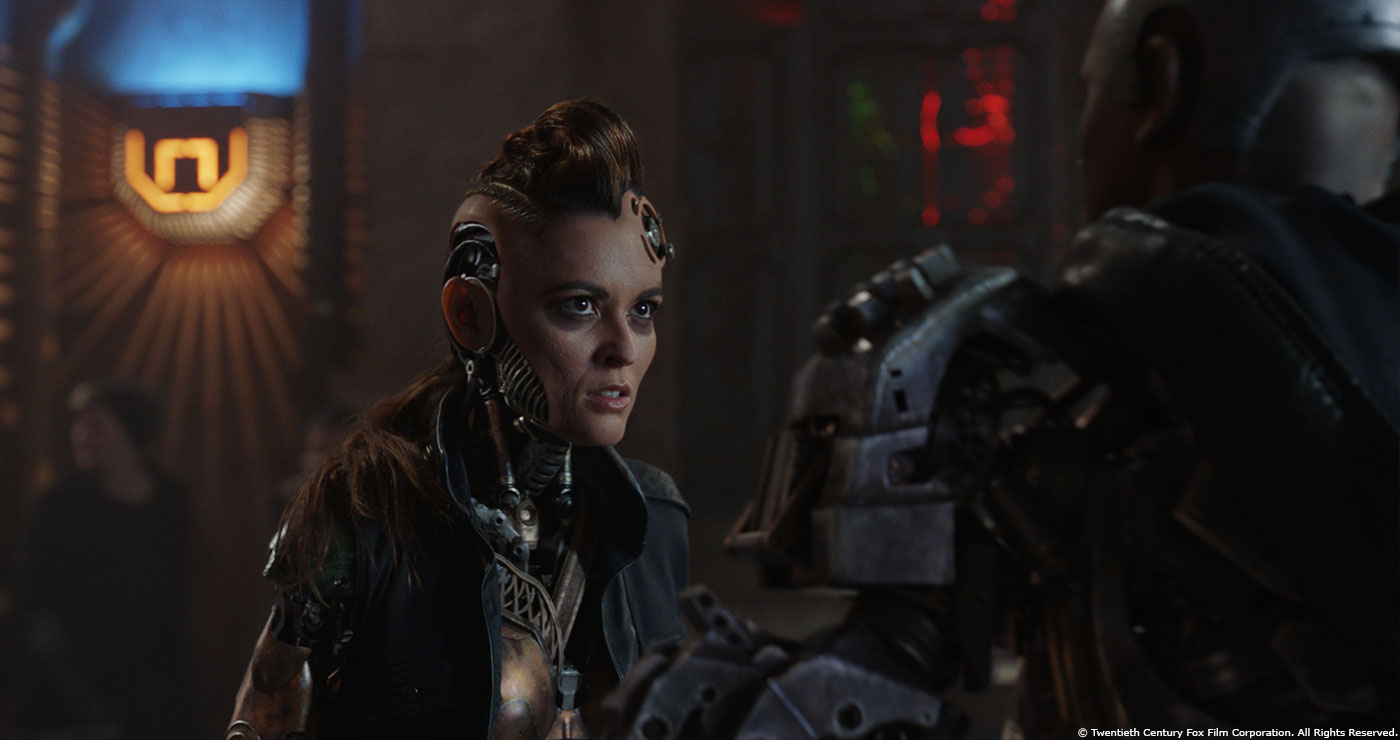

Can you explain in detail the creation of the various cyborgs?

We were given both concept art and some preliminary models of the cyborgs from Weta, but we still had to do a fair amount of design work and redo several of the models to more closely match the feeling of the concept art. We also had to make a number of design changes, once we started with motion tests, to allow the mechanical interiors of the cyborgs to move realistically. Although we were able to help with some of the design, we had to keep within the look already established within the film, to match the general feeling of other hero cyborgs.

How did you handle their rigging and animations?

The approach we took for the rigs and animation of the cyborgs was driven by motion capture. We had three rigs per character: a mocap rig, a human digi-double rig and then a creature rig, to replace the various body parts. The mocap data worked very well and enabled us to speed up the animation time needed by focusing mainly on contact between characters and the environment, along with the subtleties of hands and fingers. From time to time, animation also had to compensate for proportional changes between the actors and their new cyborg limbs; Kumaza was a good example of this because his cyborg arms became much bulkier and muscled than the actor’s!

How did you handle the extensive Bodytrack work?

We had motion-capture data for most of the cyborg actors and extras, so we started from that. We then remapped the mocap rig onto our cyborg/digi-double rig, giving us a great starting point in matchmove and animation. The added complexity with stereo cameras meant that the accuracy of the bodytrack had to be watertight.

The connection between the real actor and his CG body is really challenging. How did you manage that?

This was definitely a challenge; we created both the obvious cyborg portions of the body and also the CG double version of the non-cyborg parts, so that we could replace troublesome portions of the filmed plate, where needed. A couple of examples of this are Gangsta’s leather hood, Screwhead’s jacket, and Amok’s belt and pants.

We started with very accurate scan and texture data of the actors involved and built the CG limbs on top, from the concept designs. Amok’s design meant this was particularly difficult. We needed to keep the actor’s head and face from the plates so the integration around the neck/head area was difficult to hide and blend given the hero nature of the shots with extreme close-ups. The lookdev and simulation of muscle and skin needed to match one-to-one with the actor’s. While we wanted to maintain the legs/pants from the plate as well, there were size differences between the cyborg and the actor, especially around the waist, and that area needed to be tightened up. This was achieved differently depending on the action in the shot. Sometimes we were able to combine re-projection and warping techniques in Comp. In other shots, it was a complete replacement of the legs themselves, in effect the only thing maintained was the actor’s head. Our build supervisor, Marc Austin, along with our Creature supervisor, Fred Chapman, and their teams, built the assets to an incredibly high standard, which allowed us to pull off such hero work.

How did you handle the lighting challenges?

The on-set data acquisition helped a lot here, with plenty of great reference captured in camera. However, a lot of metallic reflections and hero creature work meant the accuracy of the lighting was significantly harder to achieve. Our lighting supervisor Mark Norrie, along with his team of lighters, recreated the sets using Lidar and projected Image-Based Lighting (IBL), and set photography, in Clarisse. An added challenge came with the addition of Alita interacting with our CG characters. While Alita was animated and rendered by Weta, we had to recreate their light rigs so the two, or sometimes three, characters could occupy the same space. For this, we worked closely with Weta to remap their light schema into our own, and vice versa, along with passing geometry back and forth between the two studios for shadowing and reflections. In some instances the lighters would project Weta’s renders of Alita onto her geometry to get bounces of colour from her arms or clothing onto the characters that DNEG was rendering.

Can you tell us more about the eyepiece for Amok?

There was an eyepiece that was created as a prosthetic for filming, but the center portion was created as a mechanical-looking iris diaphragm, like inside a camera. We were asked to create a more hi-tech robotic lens look for that interior piece. We created several concepts and then built a CG version of the selected design to be tracked into the practical eyepiece. We eventually also needed to treat the look of the rest of the eyepiece as well, since the work we did to make the metallic parts of the cyborg torso, made the practical prosthetic feel more like plastic, and it started to stand out as different from the rest of the character’s hardware.

Which cyborg was the most complicated one to create and why?

Amok.

Can you tell us more about the destruction of the bar by Grewishka?

Grewishka’s grindcutters damaged the corrugated metal of the bar, and also the wooden floor boards, before he jumped through into the underworld. We created fracturing and bending metal for the strikes into the bar, basing the impact points on Weta’s animation. For the top floorboards, we based the build on the actual floor from the set, using plates and reference photography. We also created a subflooring and concrete slab that would be revealed when Grewishka crashed though the damaged floorboards. The underworld environment revealed below was given to us by Weta. We used the geometry of Grewishka (animated by Weta) to drive the simulation of the destruction. This was one of the instances where we needed tight integration between our work and Weta’s, so there were a number of iterations before getting to the final version. In addition to the larger wooden planks, crossbeams, and concrete chunks, we also incorporated passes for dust, broken glass from the fight, and sparks from hitting the metal.

How did you handle the challenge to mix your work with the Weta Digital elements?

For our work with Weta, the shots that we shared with them were primarily composited by DNEG, even if the majority of the CG was created by Weta. In most cases, like the majority of our bar fight shared shots, this was beneficial, as it allowed us to be in control of the integration and balancing of the elements. In our reviews, we always referred back to Weta comp versions, to insure that we weren’t deviating from the look that they had already established. At times, however, like with some Grewishka shots where DNEG was only creating the background environment, we ended up establishing the color balance of the whole shot, including Grewishka, in order to create a more consistent sequence.

Can you elaborate in detail on your environment work?

The Iron City environments that we created were heavily dependent on the work previously done by Weta for other shots and sequences. However, since some locations such as the street Motorball area were not yet established, we had to design the upper levels of the city (set extension) using the design language and elements that existed elsewhere in other locations. In some cases we used assets created by Weta, but we also had to build a few sections of the city that were not used in any of the Weta sequences.

Is there anything specific that gave you some really short nights?

At the beginning of the project, getting the 3D pipeline set up was a challenge. Tim Baier, our DNEG stereographer, did a lot of great work creating a solid pipeline, but before that process was all ironed out, it did cause us a bit of worry.

What is your favourite shot or sequence?

The Ido daughter flashback sequence was a really enjoyable one to work on because it was work that wasn’t shared between facilities, which meant we could delve into it more deeply. The character was a unique one to build; we tried to convey a lot of the hardship of the fallen Motorball champion in the wear and distress on the mechanical and biological body parts. It was also a sequence that seemed to have some emotional weight within the story of the film.

How long have you worked on this show?

Around 9 months.

What’s the VFX shots count?

DNEG worked on 260 shots.

What was the size of your on-set team?

DNEG did not have any crew on set. We had around 350 people work on the project.

What is your next project?

I am currently working on TOGO, a Disney project about the 1925 sled dog serum run to Nome, Alaska.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

DNEG: Dedicated page about ALITA: BATTLE ANGEL on DNEG website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2019