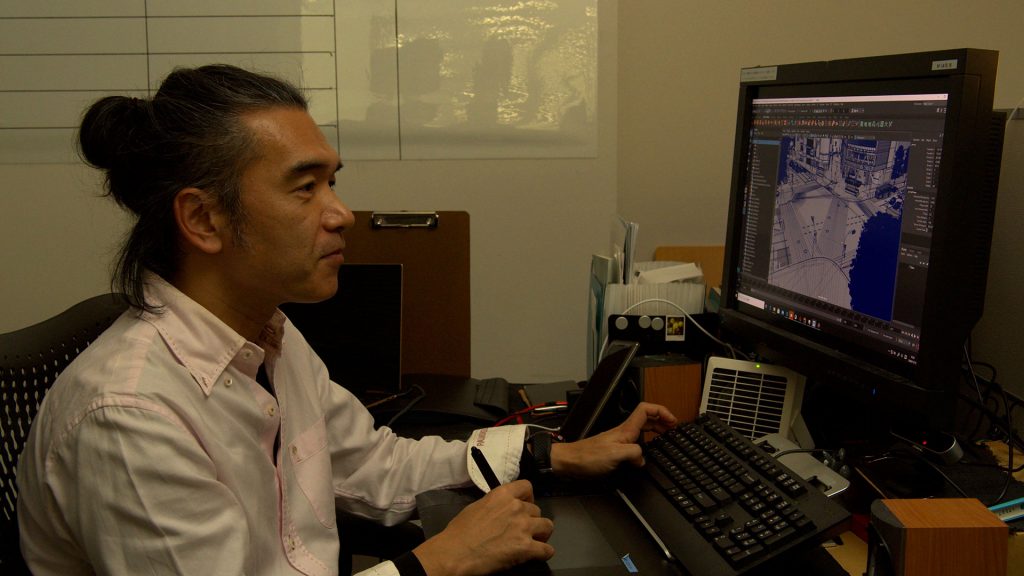

In 2018, Atsushi Doi told us about the work of Digital Frontier on Bleach. He is back today to tell us about his new collaboration with director Shinsuke Sato for the Netflix series, Alice in Borderland.

How did you get involved in the project?

I’ve been working with director Sato for over ten years. I was able to join the project because he appointed me. This is my seventh project with him.

Tell us about this new collaboration with director Shinsuke Sato.

This was our team’s first time to make a drama series. We all came together to create something that would be neither a drama nor a movie, but something new. The end result is the quality of a feature movie, if not better, going deeper than any ordinary film could. And the various stages, designing and crafting each element, were actually a lot of fun.

Many of the films I’ve worked on with Director Sato depict unrealistic worlds, but this story moves seamlessly from the real and existing world to the unreal world. So we had to make a world that viewers will feel is real, even though at the same time they feel the strangeness that comes from facing unreality. It was very good that we had overcome these challenges and produced something new.

What were his expectations and approach for the visual effects?

One new challenge, and the thing the director was most eager that we achieve, was to use computer graphics (CG) to depict Shibuya Crossing, which is well known in Japan and in the world. The director constantly insisted that it must seem real, even for details. So our VFX team carefully crafted a virtual yet detailed Shibuya Crossing, to demonstrate its importance in the metropolis, to reproduce its atmosphere and to present it as real.

The director and assistant directors shot the video storyboards of the actual Shibuya Crossing, and simulated how various angles would look if you actually filmed there. This was extremely effective because we couldn’t completely block off Shibuya Crossing for filming. Developing guidelines for how passersby would appear on the screen enabled us to decide how many extras to use for the open set, which parts we would craft in detail using CG, and which parts we would create using sets.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

Beginning at the draft script stage, we identified the assets and VFX shots we could expect for all of the scenes, and then decided how much budgetary resources had to be allocated for which aspects. We placed the highest priority on elements like the key shots, the Shibuya Crossing scenes, the flood in the tunnel, and the panther, and then balanced those efforts with attempts to achieve quality with other VFX shots (such as Tokyo at night during a complete blackout).

Can you tell us more about the previz and postviz work?

Previsualization:

We did previsualization (previz) using a virtual studio for the panther and water sequences in the tunnel. We had only a limited amount of time to close the tunnel and film on-site, so we had to have a good idea beforehand how to arrange the vehicles and how we would use the cameras. The cinematographer operated the virtual camera, getting us close to the final shot.

We made previz to decide where to shoot lasers and borderlines to find the right shot, and which colors to use. After we decided on the gimmicks, UI and design for the headgear, we used previz to decide which gimmick to use to automatically attach the headgear to the characters’ heads.

The set for The Beach was at a hotel in Shiga Prefecture, so outdoor scenes had to be created to represent a Tokyo cityscape. We tested different ways to show the hotel by making different patterns for both night and day settings, while adjusting for size and positioning.

Postvisualization:

For the external shots of the first Game venue, we had to expand the width of the filmed building and add neon signs on the roof, so we built the look of the building by postvisualization (postviz). We also used postviz to decide on the extent and spread of the fire to depict The Beach burning.

What was your approach for a Tokyo “empty” of all activities and people?

In an empty city with no people or electricity, if there was no movement the scene would look like a photograph, so we used CG to create rustling leaves, flapping flags, and moving birds and animals.

The art staff scattered litter on the ground before filming, and I believe this further emphasized the feeling of emptiness. We didn’t use any special technique to erase people or vehicles. For cuts where the camera wasn’t fixed, to erase them we used camera mapping on cleaned plates.

Can you explain in detail your work for the Tokyo environment?

It would have been practically impossible to film in all the locations required for the scenes and visually impressive at the same time in central Tokyo. So we inserted images of Tokyo into the backgrounds of the shots filmed in places outside Tokyo.

What were the main challenges for those shots?

The biggest difficulty was creating a Tokyo with no electricity at night. We either had to film at night and eliminate all of the electric illumination, or film during the day and use color correction to replicate the darkness of night. The method we chose depended on the scene.

We see many of the environments at night. How did that affect your lighting work?

The drama presents an unusual world under a complete power outage (except for the Game venues). So we had to turn off all of the lights in the scenes we shot at night. When streets and walls were actually illuminated we couldn’t turn off the lights due to filming requirements, so we edited the images to make it look like moonlight. For scenes using CG extension we had to apply CG lighting only after first erasing any city lights, and this added an extra step. For scenes that were shot in the early morning or daytime and then adjusted to look as if it were night, in order to apply the Game venue illumination to the filmed plates we had to create composites using 3D lighting for the affected portions.

Can you tell us more about your work on The Beach?

The VFX for The Beach were mainly the flames, smoke, blood splatter on people, muzzle flashes, and the hotel name change. Since we didn’t film The Beach scenes in Tokyo, we had to change the rooftop backdrop to Tokyo.

How did you create the fire in The Beach?

We used flame footage to create flames that would burn independent of the pillars, walls and ceiling. We used reflected light on the film site.

For the intense shots where the fire starts and when the flames later begin to spread through the entire building, we used Houdini to simulate all that and inserted flame images to make the flames burning the pillars and walls.

Regarding FX, can you tell us more about the water simulations in the tunnel?

If we had simply simulated real water, many elements wouldn’t have looked great, so we arranged the action by cut. The water, of course, surges forward faster than Usagi can run, but if we sped up the water too much in the edit cut back, the timing wouldn’t fit and the cuts wouldn’t connect well. What we wanted was for the water to be pushing forward but for it to still maintain a slight distance from her, and for the shot to end right before she would be swallowed up. So we tried out a number of ways to fine-tune the distance between Usagi and the water.

We had to show that the water was flowing rapidly, but if it was too fast she would most certainly be swallowed up. So we were very aware of the sense of distance and the action of the water in that cut back. If you flood a tunnel with water it wouldn’t have much movement, so we added dynamism by making the water hit vehicles, by creating splashes, and by having water rush in violently from off-screen.

Let’s talk about the terrifying laser — what kind of references did you use and what influences did you receive?

To make the laser appear realistic, we referenced images of the effect of high intensity lasers in smoke, and lasers used at concerts. While we were discussing ways to show laser beams in brightly lit scenes, someone brought up the example of the laser cannon in Star Wars, so we also referenced the laser.

We made two types of lasers: one for tracking players, and one for shooting them. For the tracking laser, we hit upon the Predator’s laser sight as an inspiration to create the terrifying feeling of being tracked.

In Mission Impossible 3, I was really struck by how the characters’ eyes change after they are shot by explosive pellets inside their heads. I used that as a reference for when the laser hits. It was the perfect way to depict the brain being burned by a laser beam.

Can you explain in detail its creation and animations?

We used intricate cylinders in Maya to animate the killer laser fixing its aim and then tracking its target. We imported that as an FBX file into Nuke and rendered animated noise textures to create the dust and smoke in the air. When a laser beam passes through someone, we painted that part of the body to show that the light had penetrated them.

Some of the games involve animals such as a tiger and a panther. Can you elaborate on their creation?

In Japan, just about the only way to see a black panther moving is to watch a video, so I took the artist to a zoo that has panthers. We filmed them to get a reference for their movements, expressions, and fur lines. Then we used ZIVA dynamics to simulate muscle action, and Yeti to depict the fur.

The panther appears in an area of a pitch dark part of the tunnel. The director chose a black panther to let viewers see only eyes flashing and moving in the dark, heightening the foreboding until they saw what it was when the light illuminated it. Because a black panther blends into the darkness, we instilled fear of its presence and ferocity by illustrating the glossiness of its coat and slightly exaggerating its muscle movements.

How did you simulate their presence on-set for the cast and the framing?

The panther sequence in the tunnel was naturally difficult for framing and depicting actors’ performances because there was nothing to be seen. Since there were scenes of the panther climbing on vehicles, pushing a door and biting people, we had the action team track the panther’s line of motion to create the reaction of the vehicles and the reactions of the characters when they come into contact with the panther.

The series is full of graphics elements. Can you explain in detail their creation and animation?

The graphics from our VFX team are the screens to invite to the Game, the massive monitors installed in the Game venues, and the interface embedded in the headgear (ep4). The content for the basic display elements was chosen by the editing department, and we inserted it in a way that fits the style of the show.

We designed the monitors in the Game venues in a very simple way even the children can understand so that it looks that the players are mocked. This made the monitor displays easy for viewers to understand, and created an ominous atmosphere because they don’t know what will happen next.

Let me tell you about the interface for displaying Sheep and Wolf motifs on the headgear. The motifs are easily recognizable even when they change quickly. Although the motifs are based on the Japanese writing (Kanji) for “sheep” and “wolf,” they morph into icons to make them intriguing even for people who don’t read Japanese.

How did you handle the challenge of the room with a countless number of screens?

The original manga has multiple monitors in a straight row, but the art director came up with the idea of using a series of monitors arranged in a cylindrical shape, to make the room seem infinite in dimension. The concept was, if there is a series of monitors it will look like all the players are controlled, thereby creating a sense of oppression while keeping a sense of reality. So we greatly increased the number of monitors over what we had originally planned based on the director’s request that he wanted the monitors to continue as high as you could see, and to make the human appearance massive.

To have at least 1,600 monitors in that space, we created multiple UV maps to easily expand the imagery.

(1) UV map that formed one monitor from all of the surrounding monitors

(2) UV map that converted sixteen 4×4 monitors into one

(3) UV map per individual monitor

(4) Cryptomatte to adjust each individual monitor

We used these with Nuke’s STmap to accommodate the various shots.

Can you elaborate on the creation of the zeppelins?

We started by asking ourselves what sort of shape the zeppelins should have. In order for even just their presence alone to instill fear, we designed them while referencing the German Hindenburg. We felt that an older design would fit the drama better.

For the zeppelins’ outer shell, the design features aluminum and carbon fiber, referencing NASA’s Aeroscraft airship.

Another important characteristic of the zeppelins is the massive suspended playing cards. We installed a rotor on each zeppelin so that they could navigate freely while still dangling the cards. We split the cards into several parts to reduce wind resistance.

Which shot was the most complicated to create, and why?

Due to the difficulty in staging it, I would say the shot where the tunnel wall crumbles and the water rushes out. This wasn’t a simple action of a dam opening to release water. We had to decide on the speed of the gushing water and how to show it bearing down on the camera when the steel beams break up piece by piece. It was quite difficult to make it appear that the characters feel that they will be swallowed up and drowned.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

It would have to be the scene where Shibuya becomes empty in a single cut. This really epitomizes this work. It is a really interesting visual where in a single cut the lively Shibuya district suddenly becomes a ghost town, and it was also a difficult shot in terms of VFX.

What is your best memory on this show?

The open set for the Shibuya Crossing scene was built in Ashikaga in Tochigi Prefecture, and I was really moved when I saw it for the first time. I had never used a massive open set like that before. The ticket gates in Shibuya Station were recreated in painstaking detail, and I felt like I was in Shibuya even though there were no real buildings.

How long did you work on the show?

The filming took around five months. Then it took about four months to get to offline editing, so before that editing we prepared assets. It took around another four months to build the composite shots. That makes approximately 13 months in total.

What’s the VFX shot count?

There were 1,311 shots in total. Digital Frontier handled 1,061 shots.

What was the size of your team?

We had 122 members. Among them, 70 were artists from Digital Frontier.

What is your next project?

Next is Season 2 of Alice in Borderland. I would expect to have more VFX even more than Season 1.

A big thanks for your time.

// Alice in Borderland – Behind the Scenes

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2021