Christian Manz began his career in visual effects at Framestore in 1997 as a runner. He then made his way in the Compositing Department. He oversaw the effects of projects such as SPOOKS, PRIMEVAL, NANNY MCPHEE AND THE BIG BANG or HARRY POTTER AND THE DEATHLY HALLOWS: PART 1.

What is your background?

I trained as an Illustrator but started Framestore as a runner in 1997. I then worked as a texture artist before moving into compositing – for commercials, broadcast and film. After being a Compositing Supervisor I moved into VFX Supervision, at first in television and then film.

How did Framestore get involved on this show?

We met with director Carl Rinsch in the summer of 2010 when he visiting London with the studio. We connected really well and he liked our creative ideas for the movie. By the November I was in LA in preproduction – breaking down the script and working out how to realize Carl’s vision for the movie.

How was your collaboration with director Carl Rinsch?

From the start, Carl and I had a similar taste in what we liked creatively. He wanted the film to have a slightly off kilter look – different from the blockbuster norm. From preproduction and through the shoot and post I worked closely with Carl, as we designed and realized the VFX aspects of the movie.

What was his approach about the visual effects?

Carl had a solid understanding of VFX from his commercials work. He prevised a couple of the key action sequences which educated how and what we would shoot. He was very interested in all of the processes that go into making a final shot.

What was your role on this project?

I was the overall VFX Supervisor for the movie, working with my producer, Garv Thorp at Universal and six VFX companies – Framestore, MPC, Digital Domain, Baseblack, Milk and Soho VFX.

Can you describe to us one of your typical day on-set and then during the post?

On set I would be where ever the biggest VFX work of the day was – be it Main or Second Unit. I would be working closely with the director and stereographer to visualize what we would be adding in later, as well as making sure we had all of the technical data to do so. In post I would review the work from all of the companies working with us – in Soho I could visit the teams and review in person. Later in the day I would cineSync with DD in the States or Soho VFX in Canada. I would then decide what I would show to the director for review and talk with him at the end of a day to get his notes. For some of the post I would be in the cutting room at Universal, which made communication with the film makers all that more easy.

How did you design the Kirin creature?

We designed the Kirin with the Framestore Art Department. Being a creature of Japanese folklore there were various references we looked at. We also had the brief that it should be large and be able to plough through the samurai like a truck. We looked at reference pictures from the internet of cows injected with steroids and combined this with the tendency for Japanese mythical animals to be big and chunky to arrive at the final design.

Can you tell us more about its creation and especially the rigging?

The Kirin had to be very bulky but agile enough to run across a field away from Samurai on horseback. It also combined thick crocodile like skin with a fleshy under belly. On top of this it had a long furry mane. All of these elements made the Kirin a complex creature to rig and animate. We utilized Framestore’s powerful tools for fur and muscle simulation.

How did you manage all the different interactions with the Kirin and the environment?

Because of the native stereo photography we make the decision early on that the Kirin’s direct interaction with the ground, vegetation etc would be CG. Therefore on set we spent time clearing paths where the creature would be running which would be dressed with foliage in post. Another important thing of course was making sure the actors’ eye lines were correct – we had a pole with a ball on the end that everyone could look at. For some shots we also added digital horses and riders so that they reacted more realistically to the huge beast in their midst.

Can you tell us more about its animation and lighting?

Movement wise we looked at how bulls run and react in a bullfight – the Kirin was meant to be slightly crazed and unpredictable so this seemed like an appropriate starting point. As we were rendering in Arnold we needed to use lighting techniques that mimicked those in filming i.e. seeing the effect of sunlight bouncing onto the Kirin from its surroundings via bounce cards. Fur shaders were adapted to be physically plausible so that they would fit into the Global Illumination pipeline and in stereo.

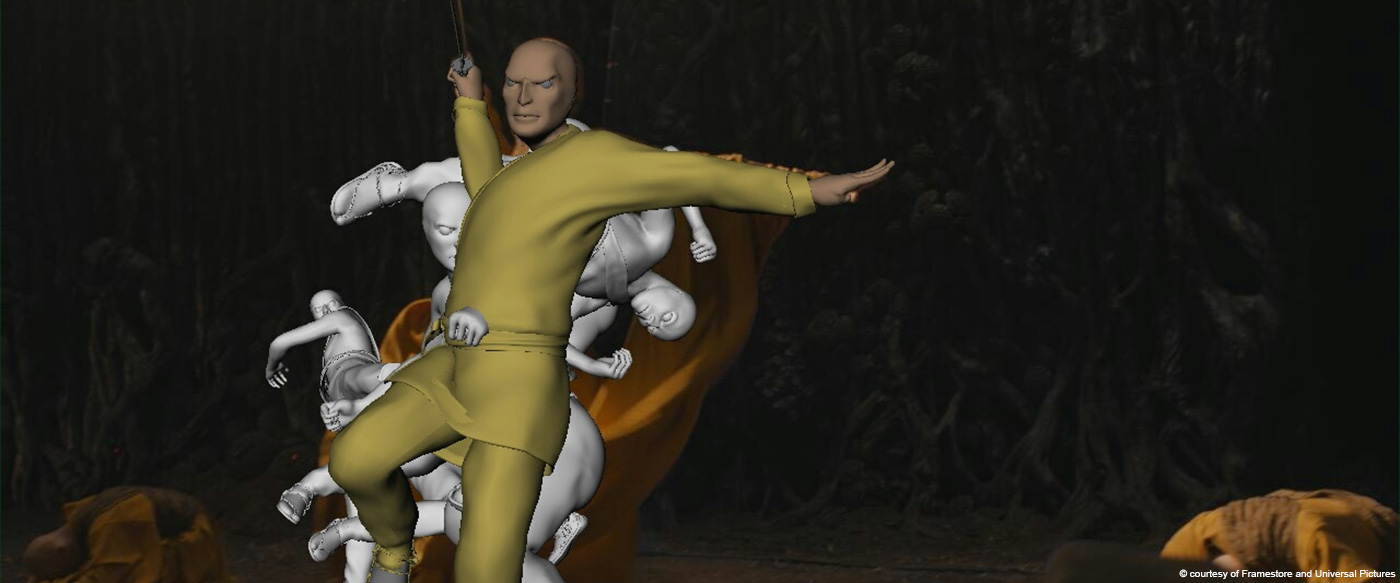

The Tengu warriors is an impressive sequence. How did you approach it?

The Tengu are Bird like warriors of Japanese myth. Carl wanted them to move incredibly quickly, as if teleporting around the Ronin. He gave me reference of Futurist paintings where movement is captured in a sculptural frozen moment in time. From this we concepted the Tengu leaving in their wake as sculptural cloth trail which would then collapse as if it is physically photographed with them. Quite early on we did a piece of concept work which we used as a reference until the last day of post.

Can you tell us more about the shooting for this sequence?

We collaborated with Stunt Co-ordinator Gary Powell, as to how we would mix the live action fight choreography with the VFX teleportations (or Bamfs as we called them). We video recorded each section of the fight in rehearsals to use as reference for previs. This also educated storyboards for the sequence as well. In the end we had two methodologies.

For the first we cast similar looking stunt performers to play the same Tengu Monk underneath prosthetics. On set the Ronin would perform the fight with up to three Tengu playing the same Monk, attacking him from different angles. In post we would paint out the Monks who were not fighting and join them with FX trails to create the illusion that it was the same person moving fluidly around the Ronin.

The second methodology was having the Ronin actor swing their sword at thin air – in post we would add a fully CG Tengu battling with them. We did this for the shots where the Tengu were moving far quicker than a stunt performer could and for quick shots where the lack of physical interaction between the combatants was less noticeable.

We shot the whole sequence motion control and at high speed – as we were shooting native stereo the large amount of compositing work was helped by the moco and the extra frames gave us the ability to play with the speed the Tengu moved in post.

How did you manage the cloth simulation and animation?

The simulation for this sequence was very challenging. The Tengu generated cloth trails as they moved, and these cloth trails needed a physical presence that would move and collapse in response to all the monks in the scene. Cloth simulation works with constant topology that does not change, as the cloth tunnels needed to grow over time this made traditional cloth simulation impossible.

We overcome this by creating a four dimensional representation of each monk’s movement over time. This was done by stamping every position the monk moved through during a shot into a single volumetric file – each monk was hand animated through its Bamf using mocap as a reference. This volumetric file was static but gave us the path the monk moved through. We could take this volumetric file and generate a mesh at the borders of the volume. This encapsulating mesh could be simulated as it had static geometry. With careful timing and adjustments we were able to control our cloth simulations so that the cloth only collapsed as the monk moved through it. This single collapsing tube could then be used to drive a dynamic growing volume and mesh which became the data that was finally rendered.

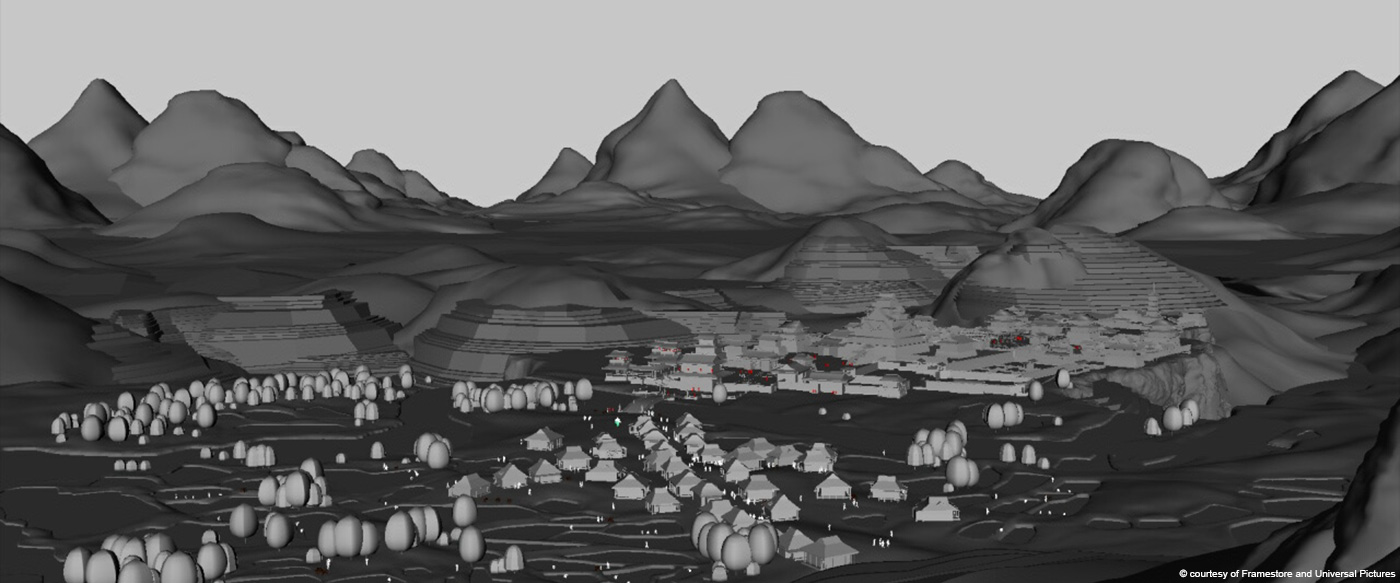

Can you explain in details about the creation of the Ako Fortress?

From early in preproduction I worked closely with Production Designer, Jan Roelfs, on the realization of Ako and Kira’s Fortresses. Both were built as huge set pieces on the back lot at Shepperton Studios. What would finally be seen on screen had far more scope than even these massive builds could give us so we had to decide which areas would be created physically and which would be CG.

For Ako a single large courtyard was constructed with a huge and very detailed pavilion running down one side of it. This set was re-dressed for various scenes to play for different areas of the fortress – we used a layout created by the production art department to get orientation as we shot and as a basis for the digital build.

The set was lidar scanned and extensively photographed by the VFX team. This data was used to model and texture a high resolution model of the whole fortress – we introduced some tiled roofs and different building types that were not in the set to make it feel that it had been built over a period of decades and to create variation.

The Seppuku scene that closes the film required the removal of a lot of the set build to create a more simplistic and pastural layout. We created CG cherry blossom trees to replace the ones in the set to save rotoscoping thousands of petals in every shot… in stereo.

Let’s talk about the beautiful Dragon. What indications and references did you received from the director about this creature?

The dragon was designed to be both a spectacular close to the film and an extension to the character of the Witch. We were inspired by Haku in Miyasaki’s SPIRITED AWAY – we wanted to create something as powerful and beautiful as him. The Witch is seen to move as cloth and have animated hair tendrils throughout the movie, so these two attributes also became important parts of the design. The Framestore Art Department worked with me to come up with a design and we hit something everybody liked pretty quickly.

Can you tell us more about its rigging and animation?

Once we had a design we started designing the movement of the dragon which, in turn, would educate how the scene was shot. I worked closely with Animation Supervisor Dale Newton from the outset – we wanted the creature to move as if underwater, like an eel but using the hair tendrils as a means of locomotion. The most difficult part of the rigging was getting a way to preview the hair, which was a CFX simulation, in animation so we could judge what the shot would look like without going to render. The hair and tail needed to be driven by animation and dynamics so our riggers worked as hard as possible to give the animators control but at the same time preserving the look of the dynamics that would add another layer of physical reality to its performance.

How did you create the CG wall of fire?

The fire jets the Dragon produces meant that Framestore had to push its fluid technology to solve gases. We used ‘Flush’ – an internal integration of Naiad into Maya. Flush allowed our artists freedom to interact with the rest of the scene within the Maya environment and quickly react to animation changes or direction from the film makers. Our RnD and shader departments pushed the fluid simulations and volumetric rendering to create the CG jets of fire that are so effective in this sequence.

Can you tell us more about the transformation from dragon to the witch?

We were keen that we see the Witch die as herself and not as the Dragon as it’s a payoff for the audience. Carl devised a single shot where we would pass over the flailing body of the dragon before ending on the Witch’s face. At first we were going to ‘cheat’ and use the passing of foreground rocks to wipe between stages of her transformation. However as the shot progressed we felt more comfortable that the rigging and simulation were up to a close-up collapse from creature into cloth. We used everything that we had learnt on the show so far to produce what is one of my favourite shots in the film.

How was simulated the presence of these creatures on-set?

Usually a tennis ball on the end of a large stick. Due to the native stereo I wanted to reduce the amount of paint out but it is also very important for the actors to have the correct eye line and understanding of what the unseen creature would be doing. I had early animation reference and concepts available on my laptop so I could show the actors what they would be facing. We also had some low-fi foam cut outs so the DP knew what he was framing for.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

The biggest challenge was the scope of types of VFX we needed to deliver in native stereo over such a long post. Also coming up with effects that ‘we haven’t seen before.’ I think we certainly achieved that with sequences like Tengu.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

The shoot of the Tengu fight was probably the time I felt the most pressure and lack of sleep along with the Dragon sequence. The large amount of VFX meant a lot of focus on myself and my team to get it right on the day and for it to look amazing further down the line.

What do you keep from this experience?

I really enjoyed working with all of the artists at Framestore and the other facilities involved. I also had a great time working with the film makers and having a significant creative contribution to the finished film. I also learnt an awful lot about shooting and finishing VFX in native stereo.

How long have you worked on this film?

I worked on the film for just under 3 years – preproduction in October 2010 until final delivery in August 2013.

What is the most challenging aspect with such a long time schedule?

The biggest challenge is keeping the team motivated and inspired whilst working on sequences for such a long time. Every artist delivered amazing work which resulted in a beautiful looking film.

How many shots have you done?

The film has a total of just over 1’200 shots of which Framestore delivered about half of.

What was the size of your team?

At Framestore, about 200 artists worked on the show.

What is your next project?

I am supervising DRACULA UNTOLD for Universal Pictures – a new take on the vampire legend.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

STAR WARS

THE GODFATHER (and PART II)

THE UNTOUCHABLES

JURASSIC PARK

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Framestore: Dedicated page about 47 RONIN on Framestore website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2014