Adam Valdez talked to us in 2012 about the work of MPC on JOHN CARTER. Then he worked on WORLD WAR Z and MALEFICENT. Today, he explains in detail about the impressive work on THE JUNGLE BOOK.

How did you and MPC got involved on THE JUNGLE BOOK?

Disney asked me to go and meet with the director, Jon Favreau. It was a great meeting where we talked about the ambitious approach to the movie. We looked at recent VFX work and dissected what did and didn’t work, and Jon identified the kinds of things he’d want us to develop if we were to work on the film. A few months and meetings later, we got the go ahead, and myself and a group of artists from London found ourselves in Los Angeles in pre-production.

Can you tell us more about your collaboration with director Jon Favreau and VFX Supervisor Rob Legato?

This movie was the tightest collaboration I’ve ever been a part of. In addition to a great working relationship with Jon and Rob, we worked directly with production designer Chris Glass, DP Bill Pope, animation supervisor Andy Jones, and editor Mark Livolsi. Producer Brigham Taylor, line producer Pete Tobyansen and VFX producer Joyce Cox were all there keeping it all together throughout. This movie required us to shoot with VFX in mind at all times, so having everyone aligned was essential. Rob was there guiding the whole shoot process, and really was like a guardian for making the film feel photographed. He’s always talking about how a real camera operator would react to action, how they would choose composition, and how exposures would be and spends a lot of time personally on color.

Jon of course was working with all of us and I think of him sort of like a combination of writer and audience, in that he’s bringing something from his imagination and taste into reality, but also constantly reacting to what he’s seeing as if he were a fresh audience. So the tone of the film, the mood and visual feel, the acting of course, and the pacing are being crafted in computer graphics along the way, and he was constantly talking to us about his reactions as it was becoming more clear.

Working with these guys in LA for the first year helped me understand them, their tastes and the process they needed from me. We were all very open and talked a lot along the way.

What was their approaches about the visual effects?

I think here we all had one goal: a magic trick. Will the audience feel like they’re really watching this kid in the jungle with animals? So the approach was, let’s not make this too spectacular or it will lose credibility. The movie has plenty of heightened moments and looks, but we tried to keep it natural and real – for a movie about talking animals!

What was your feeling when you read the script on the first time?

I was excited but also a little intimidated. Mostly because of the emotional moments the animals needed to bring to the story. How would we do that without it feeling cartoony? I’d say this was my biggest personal artistic concern. The type of visual effects all felt like things MPC had done before, but clearly the more complex the scenes were, the more difficult it would be to achieve in a full blue screen technique. I did also like the story of course, but it’s hard not to think about how to do it while reading.

Can you explain in details about the previs process?

The previs was a very mixed set of techniques over many months. Motion capture was used for some staging, including camera coverage. Traditional previs animators and TDs provided a lot of material, too. And there was a lighting effort to give the whole thing a sense of composition and mood. The art department built a lot of digital sets used in the previs, and animation supervisor Andy Jones guided the animation and motion editing required. Some scenes were done as straight previs. And all the while, editorial was trying things, and new shots and camera takes were constantly being made. So in many ways it’s a typical previs process, but in this case, it was the production designer, DP, lead actor, editor an director driving things, and I think that gave the previs a feeling more like a movie. That, and the resistance to just add tons of quick cuts and shaky cameras like we see in a lot of previs these days.

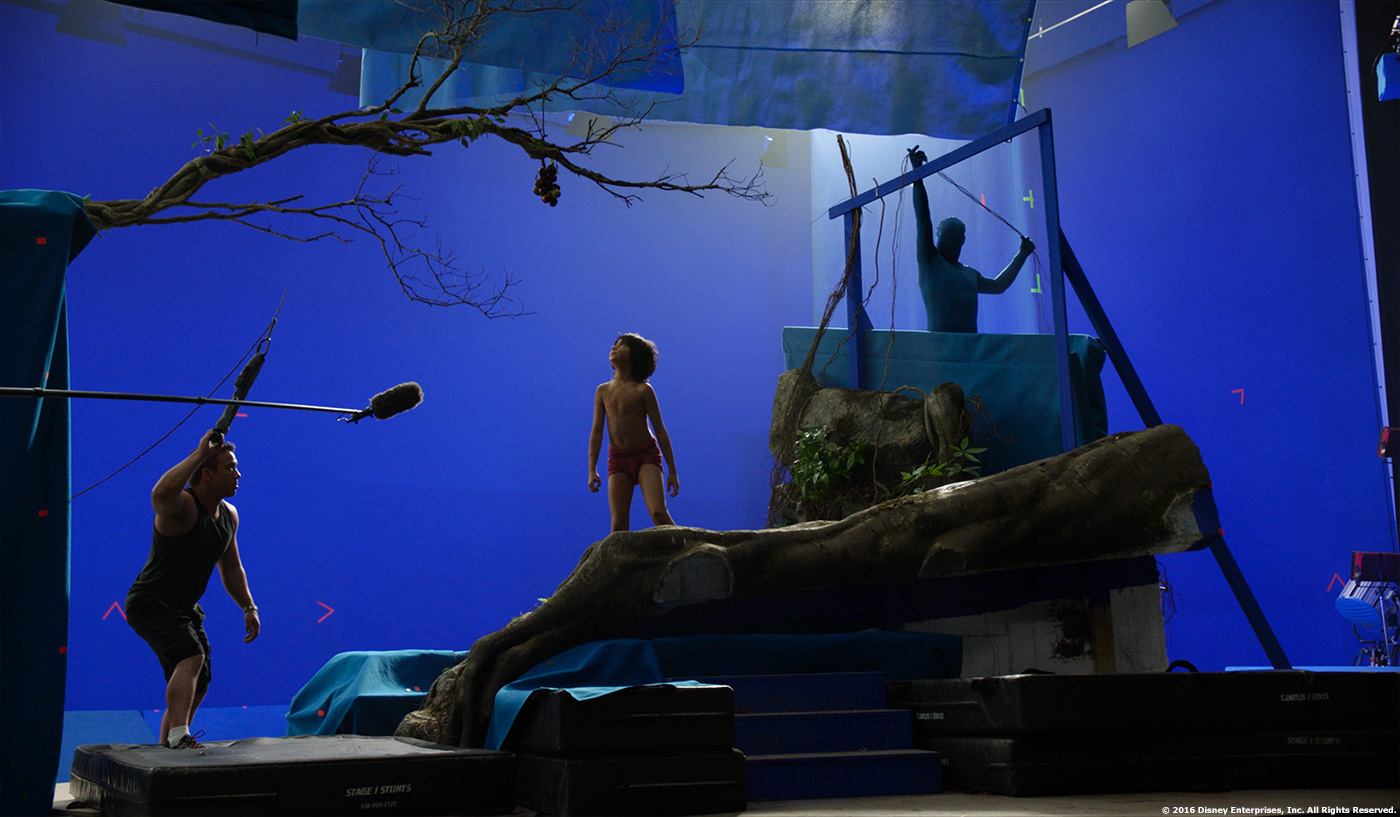

What was the main challenges of a complete blue screen shooting?

The big trick here was preparation. If the lighting on Mowgli wasn’t sympathetic to what was going to happen in the CG environments later, we would be in big trouble. So parallel to previs, MPC teams in LA were advancing set builds with Chris Glass, and doing lighting setups with DP Bill Pope. MPC’s Audrey Ferrara did the sets, and Michael Hipp did the lighting. Paul Arion did tech-viz, breaking down sequences into shoot plans. We had to help production and their art department figure out what size set we would need to build to fulfill the action for each scene. Our soundstage was tiny, and our set budget small, so we had to be very conservative with what we asked to be built. We brought the lighting plans from Bill Pope onset on an iPad, and gaffer Bobby Finley used it to set his lights on stage. This way, what we were shooting was based on the previs, but gave some freedom to shoot what Jon wanted, reacting to what our actor, Neel Sethi, was doing. The elements came back to MPC and for the most part things worked really well.

Can you tell us more about the process to help visualize the characters and the environments on set?

Simulcam was provided by Glenn Derry and Digital Domain. Glenn set up a motion capture system on set and also did realtime blue screen compositing, and the DD team who had been a big part of the previs provided the digital environments and playback. This way we could all see roughly what we were doing and how shots would compose. Not every setup used it, and handheld cameras were sometimes improvised on the spot and didn’t require these services… but most of the time it was part of daily life on the set.

Let’s talk about the iconic characters of THE JUNGLE BOOK. How did you approach their creation?

I think the design approach was always about starting with a natural image, and from there seeing if there was some stylization. We never attempted to incorporate design ideas from the 1967 Disney animated film. As usual the process begins with concept art and ends when you’ve actually sculpted something that is then fleshed out with skin and hair and walks and moves and we believe it. Everything is in flux until that day.

Can you explain in details about their design and their creation, especially about the rigging?

Ben Jones was our character supervisor on the project. He came to LA and worked with us on testing rigs and faces, then carried on developing new and better ways to simulate muscles and skin. The process of facial rigging had a lot to do with mapping out muscles that animals have that humans don’t, and making sure the face could do things like snarl and yawn and growl correctly. Then we did mouth shapes for speaking. We tested until we found a combination of animal and human muscles that felt like an animal who happened to be able to talk. We never attempted to put human qualities into their faces. The muscles and skin simulation added new complexity. Our muscles now are more of a full volumetric simulation of objects which know about each other and react to complex tensions within. The skin is a combination of cloth and spring effect ideas, but also slides really nicely and is able to introduce complex wrinkles without exploding or catching like other cloth systems.

The fur, hair and skin work are really impressive. Can you tell us more about that?

We’ve been working on our own fur grooming tools for a long time, with MPC’s proprietary tool Furtility. The team behind grooming are real artists, and the tool itself allows for a lot of delicate complexity and variation along the length of hairs, how they clump, their direction and variation in width. It’s quite powerful and I think we have the best hair/fur in the business. Of course the shading is a big part of it too and the shaders are really nice. The whole feeling has become quite natural over the years we’ve been doing it. We started doing some new simulations with Houdini on this project, which allows for more interaction between hair and water and the ground and other objects. There was a lot of development done on that early in the show.

The animation is another big part of the challenge of this show. How did you handle this part?

The animation team was really big, something like 90 people on MPC’s work on this project. Lead by anim sups Peta Bayley and Gabriele Zuccheli, and many talented lead animators, they had the massive challenge of making the characters physically believable as natural animals, while delivering emotion people can pick up on. The other trick is that many animals have zero ability to express emotion in their faces. So one of the biggest thing was a constant hunt for references. We can all relate to some things, like when a deer reacts with fright – we understand that, but how does a tiger sit down with intimidating attitude? How do wolves show intimidation? Well looking online you can find a lot of animals behaving in ways that we humans ascribe emotion to. That is a great guide, because your brain already sees emotion or attitude in the behaviour, so we used that a lot. Many clips of animal movements were found, recreated and then dialed into the shots. The animators spent a lot of time on the shots, adding delicate little touches into the shots, and if you watch closely, you’ll see the background characters are also doing interesting things.

Did you received specific indications or references from Jon Favreau for the animation?

Jon was very involved in animation all the way through. As an actor, he had opinions on how beats would play within each scene, and how the individual presence of the lead animals would evolve. There were some scenes where he would pantomime for us and provide his own animation reference. But often he would do dailies with Andy Jones (Jon in LA, Andy in London) and just give notes.

How the filming of the actors saying their lines helps your teams?

It really depends. It all helps with lip sync. Seeing how the mouth makes the particular sounds is really important. But sometimes the face or emotion on an actor’s face while they are reading a line in a booth isn’t totally in line with the final scene. Or if that actor is recording alone, they may not be looking around in the way the character is in the shot, and so it doesn’t map over one to one. In other cases, the actor might hint at a little emotional moment, like a subtext that isn’t obvious from only the audio, and that can be the secret to a great moment.

How did you manage the interaction between Mowgli and these characters?

There are key moments where Mowgli actually touches the animals. Hugging, riding etc. These are case by case solutions. Riding was done with a typical motion base setup. This had one added trick in that the rig was articulated with shoulder blades and other actuators internally which gave a more complex movement for Mowgli to ride on. We animated those scenes first, and then programmed the rig on set with Glenn Derry. Hugging moments were done onset with a puppet, built exactly to match digital models of characters. These were typically furry and the color of the actual animal. Then we’d track Mowgli and the puppet, and match up the digital animal. Often we’d have to replace parts of Mowgli with digital parts. The best example is when Mowgli hugs his mother wolf, Raksha. Here his camera side arm is digital, so that the fingers and fur could be rendered together.

Which character was the most complicated to created and why?

Baloo was trickiest. His design process was the longest, his fur is the longest, and his sandy brown color made him really hard to light. He would often look frosty or grey, or take on colors from the environment which made him look odd. His massive amounts of flesh made for some tricky deformations and physics that could get too crazy. And getting his emotion to come through his face was tricky in some scenes. We even did some shape tracking into masks that allowed comp to emphasize the wrinkles in the skin as a grade to the final fur layer, so that his brow expressions would read better. He was tough.

The environments work is also really impressive. What methodology did you develop to created them?

Digital world building and sets was easily the single biggest task on the project. Not only is the build volume enormous, but the high complexity and engineering involved to render it is also no easy task. We have LOD (level of detail) strategies in house, but it’s really hard to get each department involved (assets, sets, lookdev, simulation, lighting) to stay in sync across so much material and over 90 minutes of screen time.

The first step was having a team in our Bangalore India facility visit 40+ sites in their country, taking many thousands of photos as a basis of texture and object creation. Very little of this goes directly into the film as matte paintings. Some were used for background vistas or sky domes.

We had a budget of how many species of plant and tree we could make. We also had to monitor each scene from the camera’s viewpoint, how the animals interacted, and if we had the right species of plant, the right type of dead leaves for the floor, etc. It’s a huge puzzle in spreadsheet form to plan it. We built some pieces from photogrammetry, some from SpeedTree, some hand modeled – you name it. It formed a really big library.

Previs was a guide but the final cut also multiplied things. Audrey Ferrara who supervised all of the set work, had to bring together our layout, sets and animation departments to make sure the Sets not only looked amazing and real, but worked with all of the other needs. The set leads then divided up the movie and got into hand-sculpted hero objects, laying in the library, and then adding some procedural dressing. Scenes were then look-deved. This was a big process that Jon Attenborough lead, working closely with our lighting CG supervisor Antoine Molineau. Making sure whole scenes would light together was really tough work.

Then our technical animation lead for sets, would simulate the moving parts, shot by shot. When the scenes went into lighting and rendering, often we would have to wait quite a while to see anything because render times were really high. Lighting design frames would allow us to see into the future, but really it was often near the end that entire scenes would suddenly come to life as we put the force of the render farm on them. Thankfully, with all of these layers of intense work from so many artists, the environments, which fill 90% of the screen 100% of the time, really create the world of the film.

How the use of deep compositing helps your teams to achieve to this photo-real look?

We used deep a lot. Not all the time, because it is expensive, but when you are dealing with certain stereo issues, placing elements and layering fog into complex environments with thousands of leaves, deep can be the best way for the compositor to have fine control.

The FX are playing a important part such as river, rain and fire. Can you tell more about them?

We had one of the biggest simulation and FX teams ever at MPC. There are a few really big effects sequences: the mud slide, the river, the burning forest. But there are also other FX everywhere in the film. From interaction of feet, to pollen and smoke hanging in the air. So that team had hundreds and hundreds of shots to do. Our teams use a lot of tools. Houdini, Flowline and Maya are used for the simulation of fluids and fire, depending on which the FX lead decides is best for the shot. Sometimes multiple tools are used in one shot. We have a physics system called PAPI (Physics API) which is a wrapper around a rigid body simulator. And then our Kali system for object destruction. We used that in the mudslide sequence quite a lot.

I’m not an expert on FX simulation and the techniques, but here the team had some of the hardest natural phenomena to create, and it went down really well with our director.

How did you organizes the work amongst MPC to handle such a massive VFX show?

The production team was also large on this film. From when we started in LA, we needed support organizing the effort, then the massive builds effort, and finally the wrangling of the team which peaked at over 500 people at one time. Over 800 artists worked on the film over the course of the project, and each team has their own department management and coordination. Then the project has a central team which worked with me and the other supervisors to plan and run everyone. We sit in dailies everyday, looking at updates from every department, and moving sequences toward director presentations. We track everything like crazy. Coordinators in particular are very targeted on groups of tasks or shots, and help drive us towards our deadline. Time is always the main limiting factor in VFX, and it’s so important for someone like me and my other supervisors and production team to feel we have a plan that addresses the creative process of a director, and one which we can accomplish. We are always pushing the quality of our work, we want to deliver the best VFX possible on time and within budget. That pressure and the dedication of each and every artist is what makes a movie.

Many VFX supervisors at MPC worked on this show. How was your collaboration with them?

I had help for a long stretch from Charley Henley, another of MPC’s senior VFX supervisors. Jon Neil, Elliot Newman and Antoine Molineau were our CG and DFX sups for the project, who collectively worked on assets and look, and on keeping sequences moving. At one point we divided the show into 2 units to manage the shot volume, as if it were 2 films inside the studio. Sets and characters and animation all worked alongside both units, building everything and fulfilling the shots. In the last stretch we merged back into one unit and I worked with comp sups Dave Griffiths, Steven Kennedy, Richard Little and David Shere. I guess for my part, I’m just always trying to keep everything moving and looking great. You have to understand the vision of the director and what he’s looking for from your team. You keep in mind everything you’re learning along the way, and help the other supervisors keep those things in mind. It takes time and you need to work closely with specific people in the team. I had the pleasure of working with some really amazing talent on this show.

How did you work with Weta Digital for sharing assets and characters?

We shared Baloo and Bagheera because they had to do shots with those two characters, but actually we had very few crossover shots, under 30 I would say. That was a blessing because while it’s all possible and something we often do, it’s really hard to schedule 2 facilities sharing shots. Each studio has their own complexities to deal with but the strategies have to align at various points, and that can be tricky. I thought their Bagheera in particular was really beautiful. I was impressed they managed to create such a great version of him given that they had relatively few shots to do. So hats off to them.

What was your most complicated sequence and how did you achieve it?

I think the trickiest was when Mowgli escapes a mudslide and rides down a turbulent river. This started with ride-rig shots that were really difficult to make convincing. Then a huge and complex environment with lots of big effects simulations we worked on over the course of a year. Then water tank shots which were very hard to track and modify for the action we all wanted. And in the end all of the water simulations that had to match water tank currents. Then getting the feeling of hand held cameras, the right balance of depth and rain effects, and the final comps with all the FX simulated water splashes and fancy color work. It had all the problems: technical, creative, editorial, digi doubles. How did we do it? Lots of development time, editorial tinkering, hard work and time. It’s all about putting your team on different problems and moving them forward with enough time to give the final look what it deserves.

What do you keep from this experience?

2 main things:

First, true collaboration on all visual effects films is really about production design and cinematography making plans together. When you get your design and lighting in sync, the results feel more integrated and springing from the same source.

Second, VFX work is starting to be more about craft again. I think we’ve been through an era of technological focus, especially in lighting and rendering. For many years this was the limiting factor for most companies: Can you render something that looks real? Raytracing is a leveler. Everyone can buy it. Raytracers can now handle huge datasets, so film production will catch up with advertising in the everyday use of ray tracing. And everyone can buy Nuke, and Houdini, and all manner of great software tools. But for all companies, the trick is: What are you leveraging all these technical solutions on? What are you rendering? If the craft behind making the characters and sets is weak, you won’t create something that looks photoreal. If the animation isn’t nuanced, you will have something sophisticated and complex, that doesn’t move naturally or evoke emotion. I’m not downplaying technology, on the contrary it’s the amazing achievements of software engineers which have made this transition possible, but we are seeing a return to having more discussions about craft. Perhaps you can sense that in my answers for this movie.

Was there a shot or sequence that prevented you from sleep?

Ha. No. One of the skills I’ve worked on over the years is being able to switch off my mind when I get home. Which doesn’t mean I don’t always have some small part of my mind still working on a show, but I’m able to deal with other things in life. I do sometimes wake up very early in the morning with a head full of thoughts, and get out of bed ready to write them down and organize the day. I like waking up early so it works out okay.

How long have you worked on this film?

20 months.

How many shots have you done?

1’200.

What was the size of your team?

We had over 800 artists on the project. The peak was about 550 at one time.

What is your next project?

As usual there are things coming I can’t talk about sorry.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– MPC: Dedicated page about THE JUNGLE BOOK on MPC website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2016

Awesome interview! As usual, impressive pipeline!