Erik Nash began his career in 1979 on the film STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE. He joined Digital Domain in 1995 and work on projects like APOLLO 13, TITANIC or KUNDUN. He then became VFX supervisor and take care of the effects of films like RED PLANET, I ROBOT, PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: AT WORLD’S END. In the following interview, he talks about his work on REAL STEEL.

What is your background?

I started my career as a visual effects camera assistant on STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE and spent eight seasons as the lead motion control cameraman on the STAR TREK TV series: THE NEXT GENERATION and DEEP SPACE NINE. I joined Digital Domain and worked as a visual effects director of photography on APOLLO 13, TITANIC and a few other features, then began working as a visual effects supervisor – which is what I do today. I have been fortunate to supervise shows such as I, ROBOT, PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: AT WORLD’S END and most recently, REAL STEEL. Having started my career behind the camera it was particularly thrilling for me to be able to work in the virtual production realm where it’s now possible to direct CG characters as if they are actually present on set – just like you’d shoot a scene with human actors.

How did Digital Domain get involved on this show?

My own experience and thinking for this project sort of began back in 2008, when I had the chance to get an in-depth look at the virtual production process on AVATAR. When I read the script for REAL STEEL a year later, I saw this material as a perfect fit for a similar virtual production paradigm. I didn’t know it at the time, but one of AVATAR’s producers – Josh McLaglen – was also attached to REAL STEEL and had the exact same thoughts for this project. The topic came up in an early meeting and, as I made the case for virtual production I could see Josh nodding in agreement. Dreamworks awarded Digital Domain the visual effects contract and we launched into a six-month preproduction phase.

|

|

How was the collaboration with director Shawn Levy?

Shawn was very open and collaborative. We had a really terrific working relationship.

What was his approach to the visual effects?

His sole interest in visual effects was in how it could help him tell the story. He wholeheartedly trusted the VFX team to help him fulfill his vision.

Can you tell us about your collaboration with Legacy Effects?

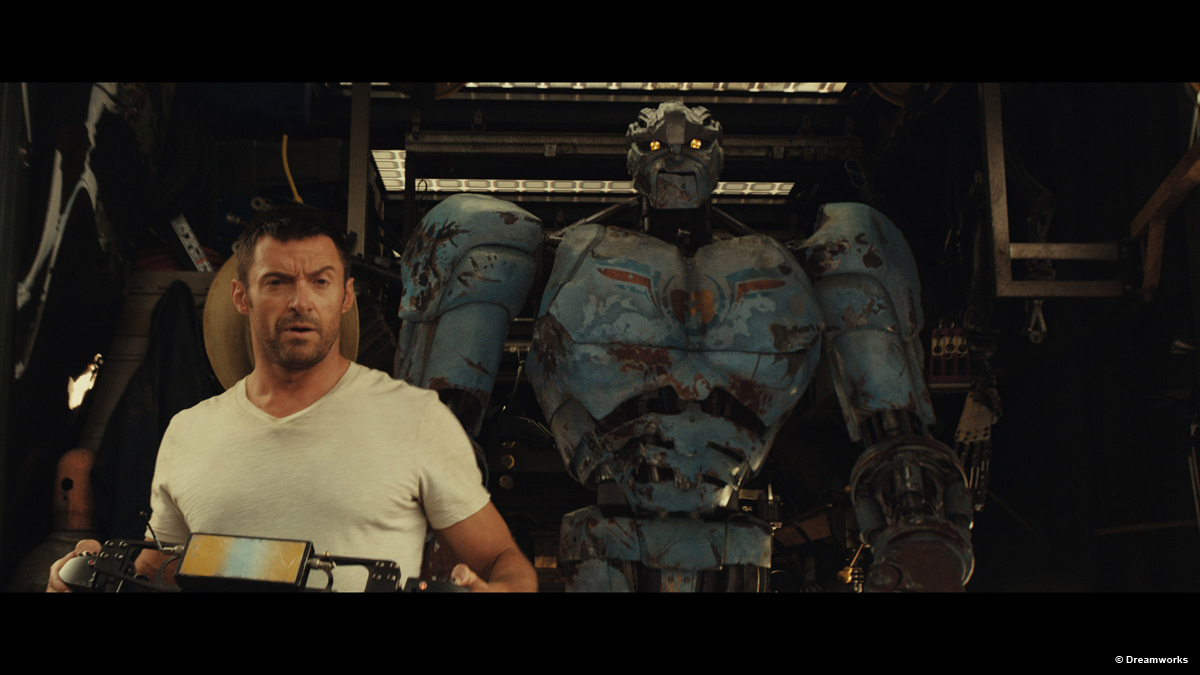

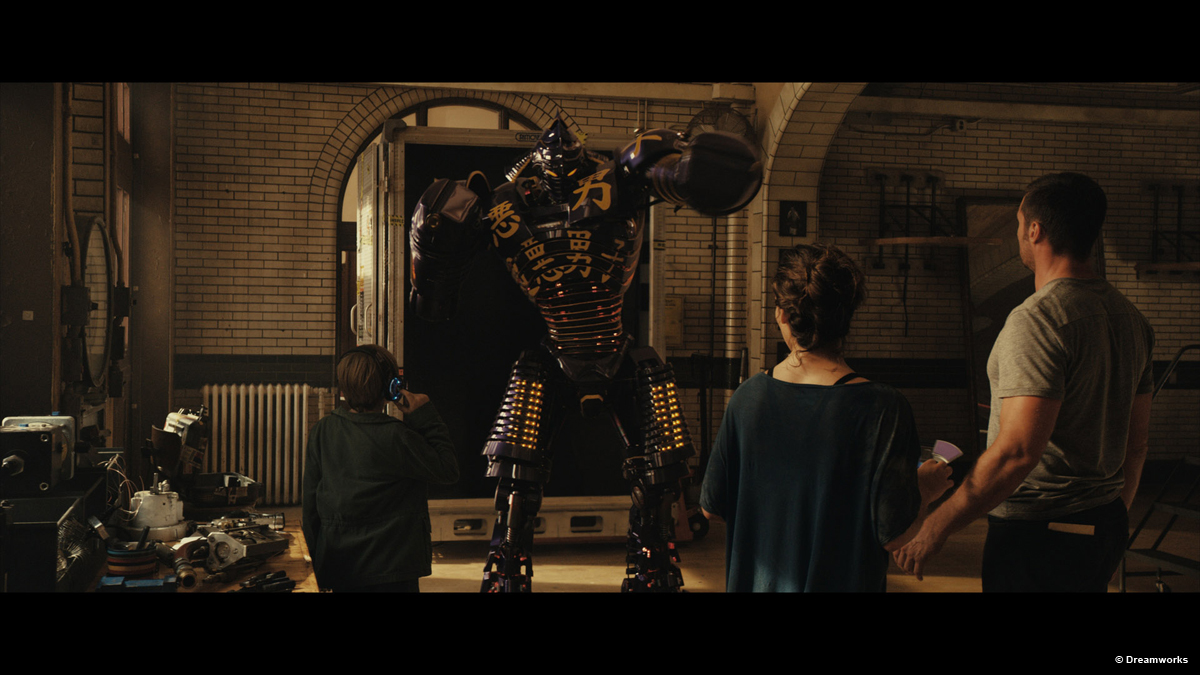

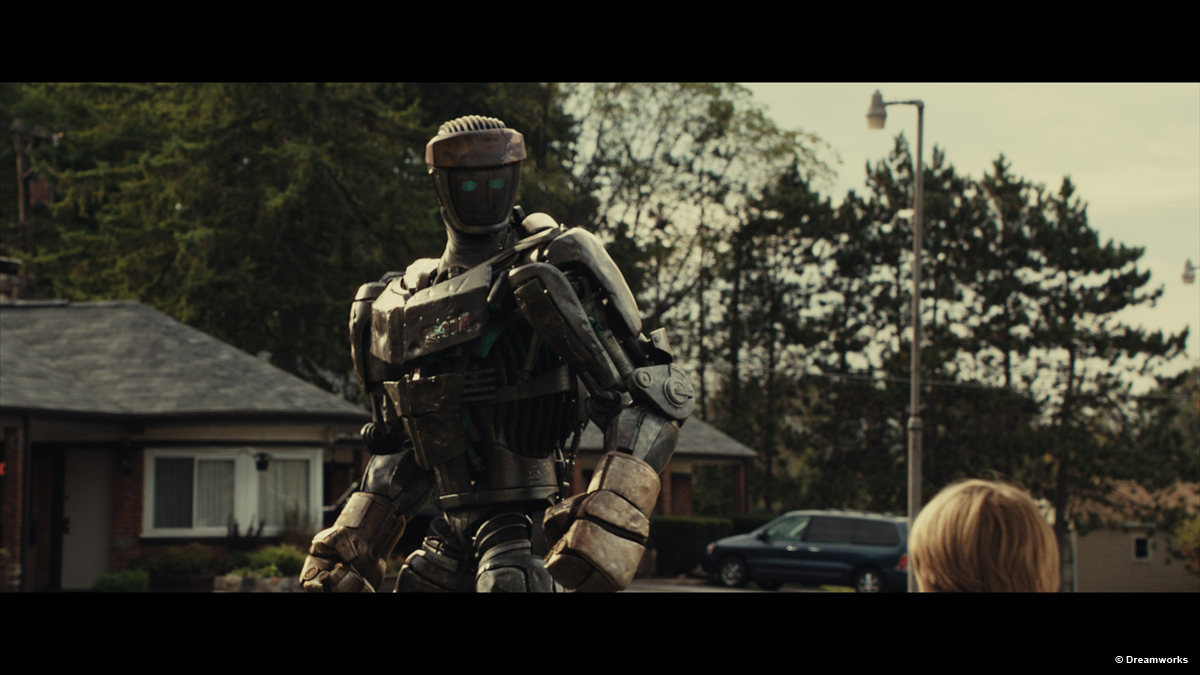

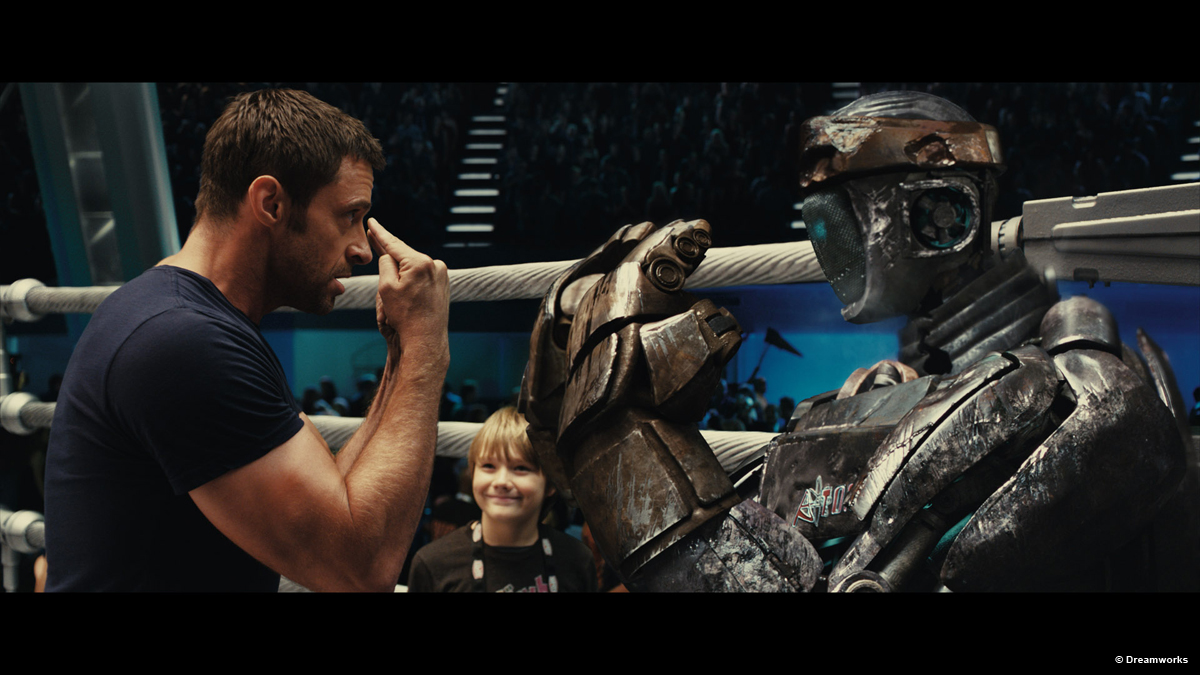

We had a great working relationship with Legacy Effects. Their supervisor John Rosengrant and I were in complete agreement regarding how the work would be best broken up. They built three practical robots – Ambush, Noisy Boy and Atom – that were used extensively throughout production for shots requiring human contact and upper body animation. We worked with Legacy and with the Real Steel production art department to finalize robot designs and mechanics that could be applied to practical robots and CG models alike, so we could create a seamless transition between the two methodologies as needed on screen.

|

|

Can you explain to us in detail the creation of the different robots?

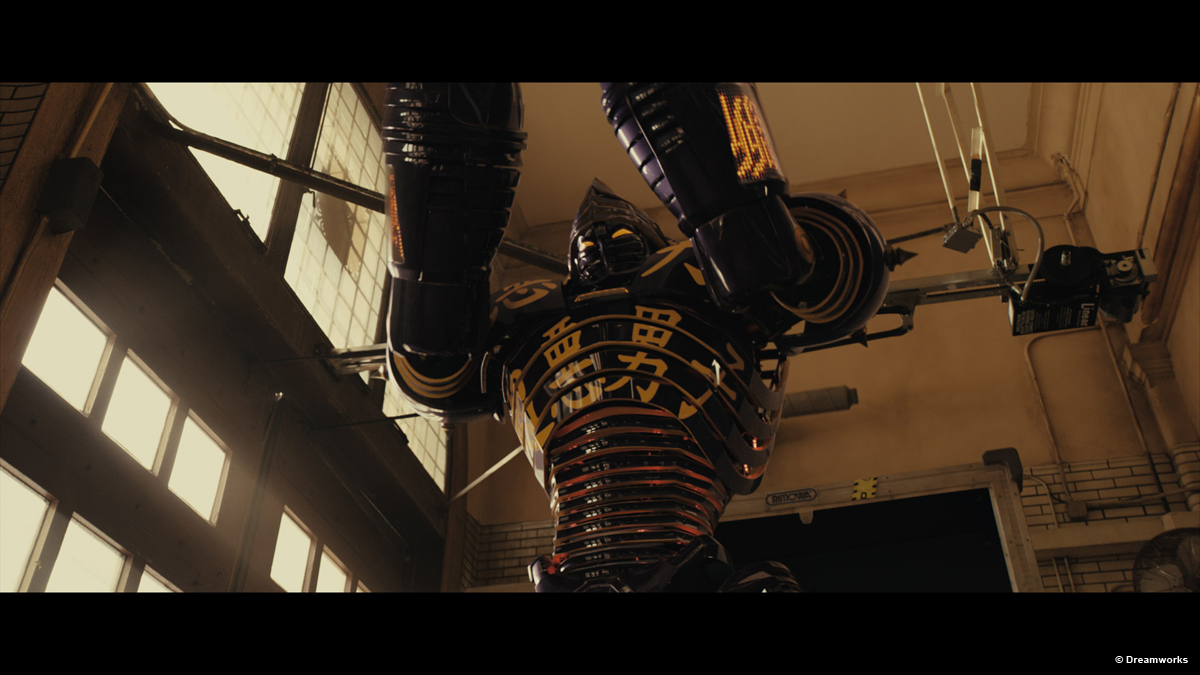

The practical Legacy ‘bots were invaluable for lighting and texture data, as they provided a tangible point of reference for digital characters that needed to be indistinguishable from the real thing. Digital Domain modeled, textured, and rigged eight unique, hero robots for the fight sequences: Ambush, Noisy Boy, Midas, Atom, Metro, Blacktop, Twin Cities, and Zeus, in addition to numerous background robots that appear throughout the film.

|

|

How did you rig them?

Early conversations between our rigging team and the Giant Studios team enabled us to get the skeletons and naming conventions worked out. Defining our nomenclature and hierarchies in advance allowed us to streamline the handoff. After principal photography, we would get a live-action plate from production and a Maya file from Giant, and we could go straight into lighting and comp, without having to worry about tracking or layout or any sort of file translation. Because our rigs and their rigs were exactly the same, there was no retargeting needed on the back end.

|

|

What were your references for their different animations?

Each robot had a different Mocap performer assigned to it. This gave each robot a distinct personality and way of moving. Each performer had a very clear understanding of the physicality of their particular robot counterpart because they were familiar with the concept art and could see their own performance applied to the Giant Studios version their robot as they were performing on the Mocap stage.

|

|

How was the presence of the robots simulated on set?

Once we had all of our fights mapped out in the virtual realm during pre-production, we brought our motion capture system to Detroit and installed it in each of our fight locations. The on-set mocap system allowed us to replay the pre-captured robot action as a live composite through the motion picture camera with complete spatial accuracy. Through the cameraman’s eyepiece and on the director’s monitor, CG boxing robots were visible in the real world set. The actors could then see playback of the recorded take with visible robots in the shot. This was a groundbreaking use of virtual production technology – it had never before been used to this extent on a film that featured so many real-world locations.

Did you create some previs to help the shooting?

For the Metal Valley stunt sequence, Previs Supervisor Casey Schatz modeled all of the camera cranes, lighting rigs, rain bars and stunt rigging that would have to be fit into a very confined area around the set. This allowed all of the department heads to see how all of this huge equipment had to interrelate. We used the previs to figure out how we were going to set up everything on location. When we actually got there, everything went in exactly as we’d planned, and we were able to shoot that very complicated setup in three short nights.

|

|

Digital Domain worked on the TRANSFORMERS trilogy. How did this experience served for this show?

The biggest help our TRANSFORMERS experience gave us was organizational and managerial. The greatest similarities between the projects were the quantity and complexity of the work. Stylistically, the projects were very different.

How did you made such great realistic renders for the robots?

DD’s “Light Kit” system, which was originally developed for BENJAMIN BUTTON, produces near-final lighting renders right out of the box using high dynamic range (HDR) images captured on set during principal photography. Once the compositing, integration and lighting teams properly format the HDRs, the resulting 360° digital worldview of each location is ingested by our software pipeline for lighting CG characters within that environment. Typical HDRs are used as an infinite ray dome; on REAL STEEL we projected the HDRs onto 3D geometry and actually traced it in 3D space. Thereby the lighting is much more physically accurate. As our CG character moved through the set, it would get all of the influence of the HDR in the proper three-dimensional space.

|

|

Can you tell us more about your work on the futuristic city?

There really wasn’t any “futurization” done thru VFX. All of the cityscapes were achieved in-camera on location in Detroit, Michigan.

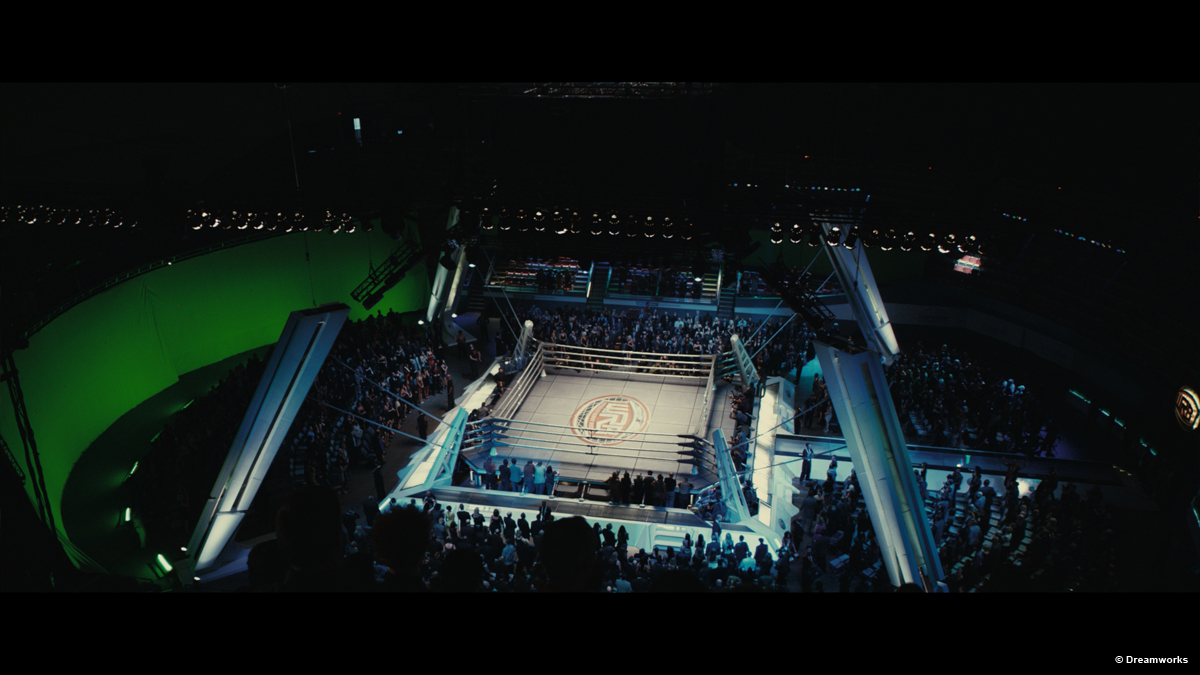

How did you create the huge arena for the final fight?

Production Designer Tom Meyer and his art department delivered concept art and a 3d model of a fictional 20,0000-seat sports arena. Our environments team led by Geoff Baumann and Justin van der Lek modified the design to fit the footprint of Cobo Arena in Detroit where the sequence was shot. Then the entire interior was model in detail, textured and lit to match the practical, partial set. We then populated then arena using a crowd system developed specifically for REAL STEEL.

|

|

Did you develop specific tools for this show?

The use of virtual production technology – a process we tailored specifically for this film – was the biggest innovation. Virtual production had never before been used this extensively for a location-based feature.

Also, our digital effects supervisor Swen Gillberg and our environments team devised a new crowd technique dubbed “Swen’s Kids.” Eighty-five extras were replicated photographically at very high resolution to achieve crowds as large as 20,000 spectators in the arena fight sequences. The process started with individual extras against green screen who would go through a scripted series of movements – seated, standing, clapping, arms raised, etc. – that were captured by three digital cameras positioned at different angles. The three cameras ultimately captured over 80 terabytes of HD footage. A software tool was written within Nuke to manage the footage and allow for easy replication of crowds depending on the needs of each shot, including factors such as crowd size, proximity to camera, enthusiasm level and camera angle, among others. This system was used to produce anywhere from a handful of background spectators to a crowd of thousands, all generated through an easily managed system that required fewer computing resources than a full 3D solution.

|

|

Was Digital Domain Vancouver involved on this show?

100% of Digital Domain’s work on REAL STEEL was done in Venice, CA

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

The biggest challenge was figuring out a way to create eight-foot tall working robots that could do battle in a boxing ring and look entirely believable doing so. Our virtual production process was a key front-end solution to meeting that challenge.

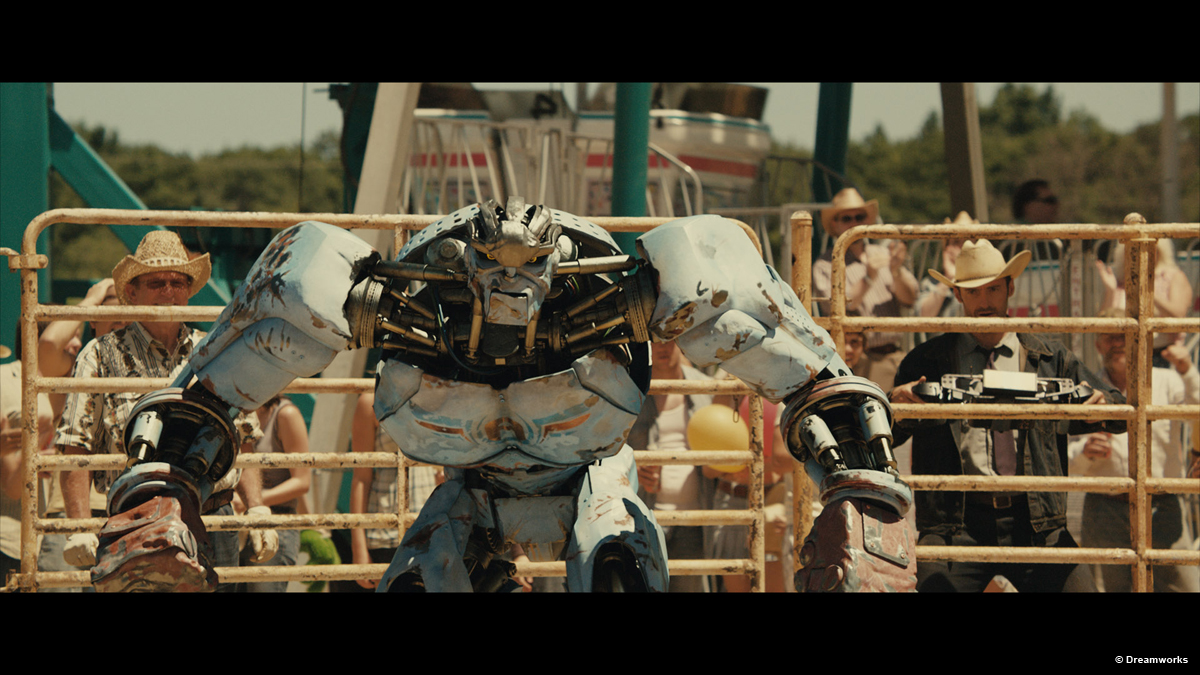

Was there a shot or a sequence that kept you up at night?

The scene with the bull at the beginning of the movie was the most difficult. Flesh and fur is much harder to achieve digitally than metal.

What do you keep from this experience?

REAL STEEL stands out for me as by far the most rewarding project I’ve been involved with. Working with Shawn was incredibly collaborative and fulfilling. The work that our team at DD produced is as close to seamless as I could ever hope. It is a movie that I will always be very proud of.

|

|

How long have you worked on this film?

We worked on REAL STEEL for about 19 months total – starting with early prep work in December of 2009, through to final delivery in June of 2011.

How many shots have you done?

Digital Domain produced 626 VFX shots for Real Steel.

What was the size of your team?

Digital Domain’s team reached a maximum of 250 people, including artists and production support.

What is your next project?

We’re currently looking at several projects, but don’t know what will be next.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, CHINATOWN, BRAZIL and THE BIG LEBOWSKI.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Digital Domain: Dedicated Page about REAL STEEL on Digital Domain website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2011