In 2010, Simon Otto had explained in detail about his work at Dreamworks Animation on the first episode of HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON. He then worked on several shorts inspired by this film. He is now back with the second episode.

That’s your second movie with director Dean DeBlois. How was this new collaboration?

I have now been working with Dean for a good 5 years. Dean solo – directed this second film, since his co-director of the first Dragon movie, Chris Sanders, had already committed to helm THE CROODS, which was being produced at the same time. Besides that, a good chunk of the animation team remained the same with some of the most senior animators returning to oversee their characters from the first movie. So, this time around we were already a pretty well oiled machine. Dean took advantage of that and gave us a lot of room to play, which was fantastic. Dean is incredibly collaborative, but also immensely artistic, story savvy and sure in his vision. His ability to eloquently describe what he needs out of each scene and where we could explore, allowed us to be incredibly efficient and yet bring a lot of ideas to the table.

What was your feeling to be back in this universe?

I never really left, actually. After the first movie, I briefly worked on a Dragon Christmas special and then immediately started storyboarding and designing for this sequel. When Dean first pitched his vision for HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON 2 to me, he basically described two images: What if when we meet Hiccup again, 5 years have passed and he and Toothless are out there, mapping out the world. And what if on one of these journeys, Hiccup comes across this mysterious dragon rider who is years ahead in dragon skill s and eventually reveals herself as his long lost mother. I was immediately sold and excited to get back into it.

Can you tell us more about the scout location trip in Norway?

The trip was mainly a leadership bonding experience where you start building relationships and talking about ideas inspired by the world around you. From a production design world, you want to be inspired by your surroundings but you don’t want to be limited by your research. For me, it was mostly about visiting the museums and getting the flavor of the Sami culture. The trip was successful more in terms of the time we got to spend with each other talking about the characters and being away from studio life.

The main change is the age of the characters. How did you approach this aspect?

It became clear very quickly that the decision to age up the characters would come with challenges and opportunities. The opportunity lied in the fact that we now had the chance to improve on our designs and create more sophisticated characters as well as taking advantage of our giant technology push that has taken place at the studio over the last 3- 4 years. The challenge was to remain true to these beloved characters that our audience now identified with. The first important decision was to not really go back to drawings and instead shape the legacy characters directly as 3D models. We hired Leo Sanchez, who was instrumental in modeling some of the main characters on TANGLED. We did a lot of drawings and drawovers, particularly for outfits and hairstyles, but it was all done to help shaping the characters directly as models in ZBrush and Maya.

Not only did we want to age up the characters, we also wanted to age up the tone of the film and for that we needed to make Hiccup more aspirational. We struggled with that, because we were afraid of turning Hiccup into a generic good looking leading man, while loosing the dangly charme of young Hiccup from the first movie. We ended up finding the balance in the design through several iterations and trusted that we would be able to instill Hiccup`s familiar quirks through his posture and gestures. Dean even wrote a scene early on in the movie, where Astrid mocks Hiccup’s geeky nature that gave us that opportunity to illustrate that the core of the character was still there.

Can you explain in details about the creation of the characters and the dragons?

We were working on two fronts, really. Our plans of growing up this world also meant expanding our universe as a whole. So, while we were working on creating believable and appealing teen kids on the one side, we also needed to expand our cast of dragon characters on the other. One of my personal goals was to make the dragons more creature like without sacrificing the fun aspect of their designs. I was looking for more anatomical structure, which wasn’t easy considering the number of different unique dragons we were planning on creating. We modified all of the legacy dragon designs slightly in their structure, added more detail and definition in the model and redid the surfacing from the ground up. I initially was striving for a lot more muscle and sim based rigging, but we ended up compromising in that area quite a bit, since we needed to have such a vast set of different types of characters. The size of our cast was probably our biggest challenge in rigging and asset creation.

Instead we focused much more on developing truly unique and entertaining dragon ideas and behaviours. All of our dragons’ character designs and behaviours were essentially constructed through mixing and matching of interesting characteristics we found in the animal world or in objects with character surrounding us. Things that gave us the right type of character for the story or that would go well with the matching dragon rider. Skullcrusher, Stoick’s dragon for example, is a cross between a rhino, a truffle pig, a dung beetle, a jackhammer and a battle-ax. Cloudjumper, Valka’s dragon on the other hand is a cross between a Grey Owl, a proud Great Dane, a Vampire Bat and an X-wing star fighter. This sounds silly at first, but when you create little movie collages with these elements you start to see the flavor of the character. It helped getting everyone on the same page.

The technology was a big factor in the set up of the characters. We were the first show taking advantage of Apollo, our the next generation software package, which was timely, considering our gigantic appetite for sophistication and scale. Apollo allowed us to add a lot more detail to both the dragon and human characters and even work with them much more efficiently. Now when I am animating I can see the characters full rez and deform the characters real time by touching and moving the geometry. We streamlined the workflow, eliminated all the clutter in terms of interface and we also don`t generate playblasts (movies) anymore. A lot of animators switched to stylus and Cintiq due to this intuitive, interactive worklfow, actually. Our hardware and software can process so much more information and immediately cache models through parallel processing that we don`t change resolution anymore. This influenced a lot of design decisions, of course. If you compare Hiccup from the first movie to the sequel, you can see how his design got much more detailed in terms of his face and hair. We also had the freedom to build Hiccup’s improved flight suit without having to budget how much geometry we could carry efficiently. It allowed us to make a true design statement that immediately described the time that had passed.

Does the change of age affect the animation of the characters?

Yes, definitely! Just as with Hiccup, after we had accomplished the aging up process, we needed to make sure we find the essence of the characters from the first movie in the animation, while giving them a slightly older behaviour. More importantly though, the fact that we were telling a more dramatic story with darker themes and the added realism in the design of the world affected the animation significantly. We had to make make sure our characters remained believable in this setting and that we were delivering on the emotional aspect of the moments.

There are great flying and skydiving sequences in this new episode. Can you tell us more about it?

There really are three important aspects to creating great flight sequences in CG. The first one is the shot selection and the way you stage such a sequence. We were challenged on this second movie to come up with ideas that could give the audience a fresh experience. That wasn’t easy as we had already covered a lot of ground in Dragon 1. The story and previz guys came up with a lot of new ideas, such as Toothless blasting fire to keep Hiccup from descending too fast or certain types of locked on camera shots that really take the audience into the action. The second important aspect was that animators needed to truly understand the physics and mechanics of organic flight. How do you describe the air that is essentially invisible? Properly illustrating weight, lift, drag, turbulence etc. was key to making it all look believable.

This was already really important to me on the first movie. On both films, animators had to go through a two week `flight school`; a training class during which they had to do very specific animation tests, such as a simple wing beat, a take off or a landing for example. A lot of animators worked on the first movie, so it was a bit easier this time around, because I think a lot of us had learned a lot from animating so many flight shots on the first movie. And then lastly, you need really solid tools, such as our flap cycle system, path tools and 3D viewers tracking with the characters.

Just as with any action scene, I believe that above all, the success of a good flying sequence lies in the fact that you`re rooting for the characters. Otherwise it`s just empty fluff. I hope we managed to do that.

Did you used specific references for those sequences?

We looked at a lot of reference in general and kept sending our latest findings to each other. There might be some direct reference in a few specific cases, but mostly we were just trying to understand it. Our character effects lead, Oliver Finkelde flies wingsuits, so we talked to him a lot. He shot some videos on his jumps for us and then lectured us on the basics, such as how to control your flight and how you position your limbs to achieve what you want. For Hiccup`s solo flight scenes, that was incredibly helpful.

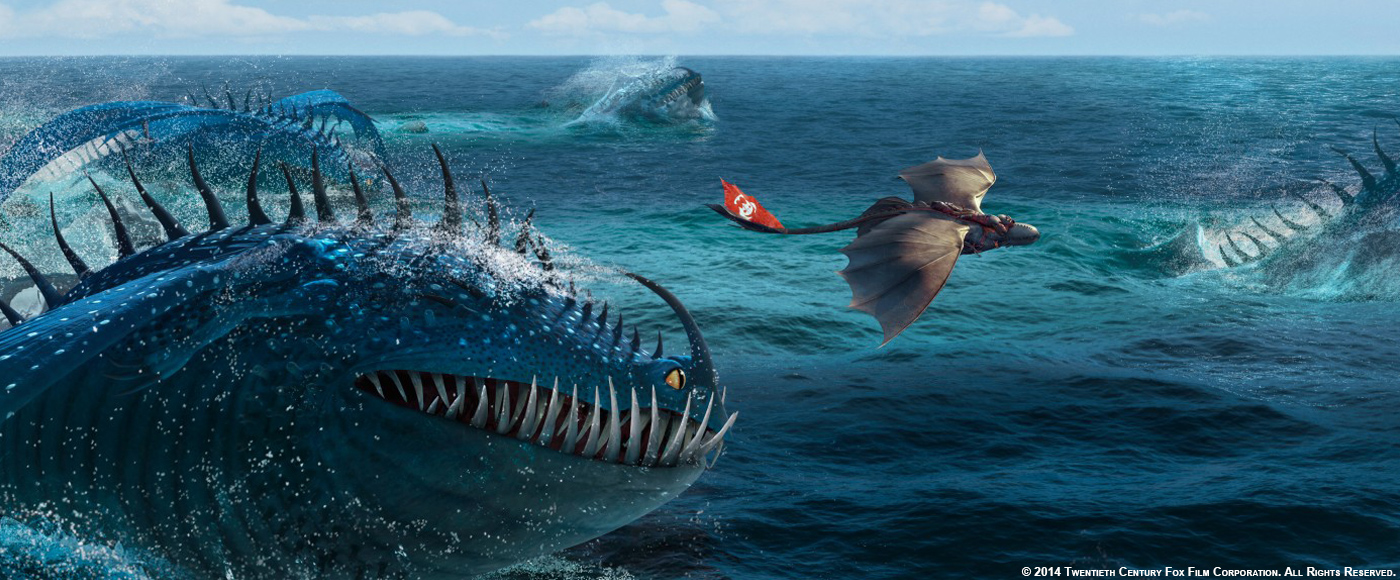

Can you tell us more about the Alphas animation challenge?

I find that the hardest part about your big bad creature is to find something that hadn’t been done before and find a good reason to be original. It’s not so hard to be original, but it’s hard to be original AND fit the story you’re trying to tell. For us, that challenge started during the design phase. After quite a bit of trial and error we settled on a mix of wholly mammoth, regal lion and otter. It was our production designer, Pierre-Olivier Vincent, who suggested that instead of a fire breathing dragon, this behemoth could spew ice instead, which really was the key idea that influenced most decisions for this character. It also needed to be a sea creature, so that its presence could be revealed at the right moments. So, its wings had to function as fins as well. In order to visually sell its scale, we needed to add a lot of smaller elements to the design. The amount of secondary detail that this dragon had was beyond anything we had previously done at the studio. Its crown, antennas, spikes, fins all had to be animated , not to mention the spike-filled tail.

We were incredibly lucky that Jalil Sadool had joined the studio not too long before. He had come from Weta and had previously worked on AVATAR. He brought amazing creature animation sensibilities to the task. We assigned him with the lead animator position and he really sank his teeth into the character and did a phenomenal job. Besides him, we only cast really strong creature animators to the character, who could handle the weight, scale and complexity of the Bewilderbeast. This type of animation is not usually the strong suit for an animation house such as DreamWorks. I’m incredibly proud of the result though.

What are the main changes in your pipeline for this new episode?

The major pipeline changes happened in lighting and animation, where we swapped out our entire software packages with the first versions of our shiny new tools that are significantly more artist friendly and allow for iteration and faster computing. The chain reaction of that was that we needed upgrading in almost every area, from surfacing to previz to rigging. We became the Guinea pigs for what future productions at DreamWorks will look like. This much change was challenging at first, but it ultimately allowed us to achieve goals that we wouldn’t have otherwise been able to achieve.

Can you tell us more about the collaboration with Intel?

Intel and HP are DreamWorks’ key technology partners. For the development of the underlying software architecture we had several Intel developers working on campus side-by-side with our engineers. The goal was to understand how to fully take advantage of upcoming versions of graphics cards and processors and integrate and plan for current and future cloud computing possibilities and overall processing scaleability. The success story for us was that we were heavily involved in the planning phase of the tool that we have on our desks today. The studio came to us about 4 years ago and asked us how we would want to work if speed and complexity would no longer be an issue. What followed was an extended and very successful collaboration between a few key animators and a team of highly skilled software developers. It’s by far the best animation software I have seen.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

The toughest part about making this film was that it was a sequel to a beloved movie. It’s incredibly challenging to follow up on something that you worked so hard to create in the first place and not to disappoint yourself and everyone else along with it. Aging up the kids and telling a story that truly progresses from the first movie was a n important move to overcome this and a reason why I felt this was a challenge worth taking. You can almost not compare the two films and the experience of watching it satisfies the desire to revisit this world, but at the same time it takes you to a whole new place.

On a complexity level, what really made this movie a huge challenge for us, was the fact that now all the kids were flying dragons from the beginning to the end of the movie, whereas in the first movie, they really only started riding their dragons in the third act. This, along with the fact that we had a slew of new characters, including armies of dragons and humans, made this movie incredibly labor intensive. I believe we animated about 30-40% more character footage in comparison to the first movie.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

I don’t loose sleep over work anymore, which is probably more related to the fact that I’m just too wiped out at the end of the day. But it’s usually one of the first 3 sequences that are the most tricky, because everyone is so focused on how the characters ‘feel’. It’s when the executives and producers really get to see what they have been spending their money on. In our case that was the sequence with the interplay between Astrid and Hiccup at the beginning of the movie. It was while we animated this sequence that we first got to see what their 5 year relationship would be like and how they compare to the first movie as characters. We weren’t quite sure whether we nailed it or not and decided to move forward to see the sequence in context later on. By the time we got back into it, we had learned so much about the characters and what worked and what not, that we ended up changing only a few key things.

What do you keep from this experience?

I really loved working on this movie with this team. Everyone was incredibly motivated to create something special. It reminded me of how important it is to have a motivated crew and to give people the chance to make an impact on a movie. That’s what we’re all here for. It’s that feeling that I’ll take with me and that I’ll probably seek to recreate.

How long have you worked on this film?

I started storyboarding at the end of 2010 and ended animation in April of 2014. About 3 1/2 years total.

What was the size of your team?

We started with 3 animators and peaked at 42. Our average crew size over the 16-18 months we were working on this movie was 24.

What is your next project?

I’m not sure what I will do right after my vacation, but I should be back storyboarding on DRAGONS 3 by the end of the year.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Dreamworks Animation: Official website of Dreamworks Animation.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2014