Pavani Rao began her career in visual effects in 2005 at The Orphanage. She then joins Rhythm & Hues and work on many films such as THE GOLDEN COMPASS or THE INCREDIBLE HULK. In 2009 she moved to Weta Digital to work on AVATAR. She then worked on RISE OF THE PLANET OF THE APES, THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN and the HOBBIT trilogy.

What is your background?

I studied architecture in college and was introduced to computer graphics as an architectural visualization tool. I was very attracted to visual effects for film and pursued a Masters degree in computer graphics. After graduation I did look development and lighting at Rhythm & Hues for 4 years before moving to New Zealand to work on AVATAR in early 2009.

How was the collaboration with director Wes Ball and Production VFX Supervisor Richard Hollander?

Wes and Richard were fantastic to work with. They had a clear idea of what story the VFX was supposed to tell, but open to ideas on how to achieve that final imagery. They were very generous with praise, and their critique was built around collaborative discussions. When Wes said « it’s badass » we knew we were on the right track! This was a huge motivating factor for the crew.

What was their approach to the visual effects?

They were very closely involved every step of the way from pre-production to final shot approval. They were very communicative with frequent cineSync reviews. This was especially handy in the pre-production stage to get buy-off on design before building final assets. They were always excited to see in-progress components of shots, whether it was FX simulations or look development concepts.

The movie presents a post-apocalyptic world. How did you approach this aspect?

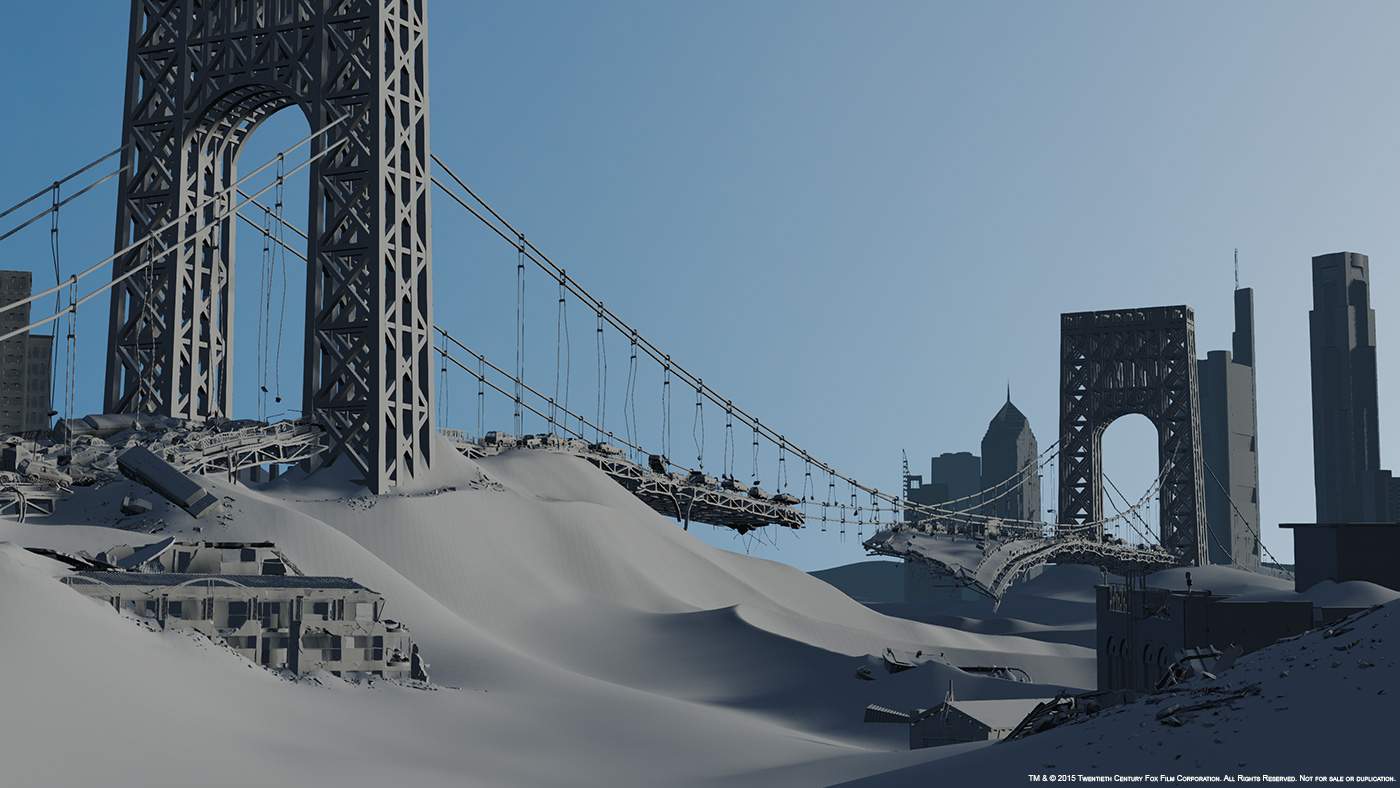

We started the design process by looking at references of skyscraper cities around the world that matched the scale and density that Wes was looking for. We then built an entire 3D city without destruction and dropped in previs cameras to get a sense of this space. We then proceeded to create damaged variants of the buildings based on real-life references of structures destroyed by fire, earthquakes, war etc. We would try and tell a story with the way we damaged the buildings, perhaps there was a fire that caused a section of the roof to collapse and you can see that narrative when you see the rendered model.

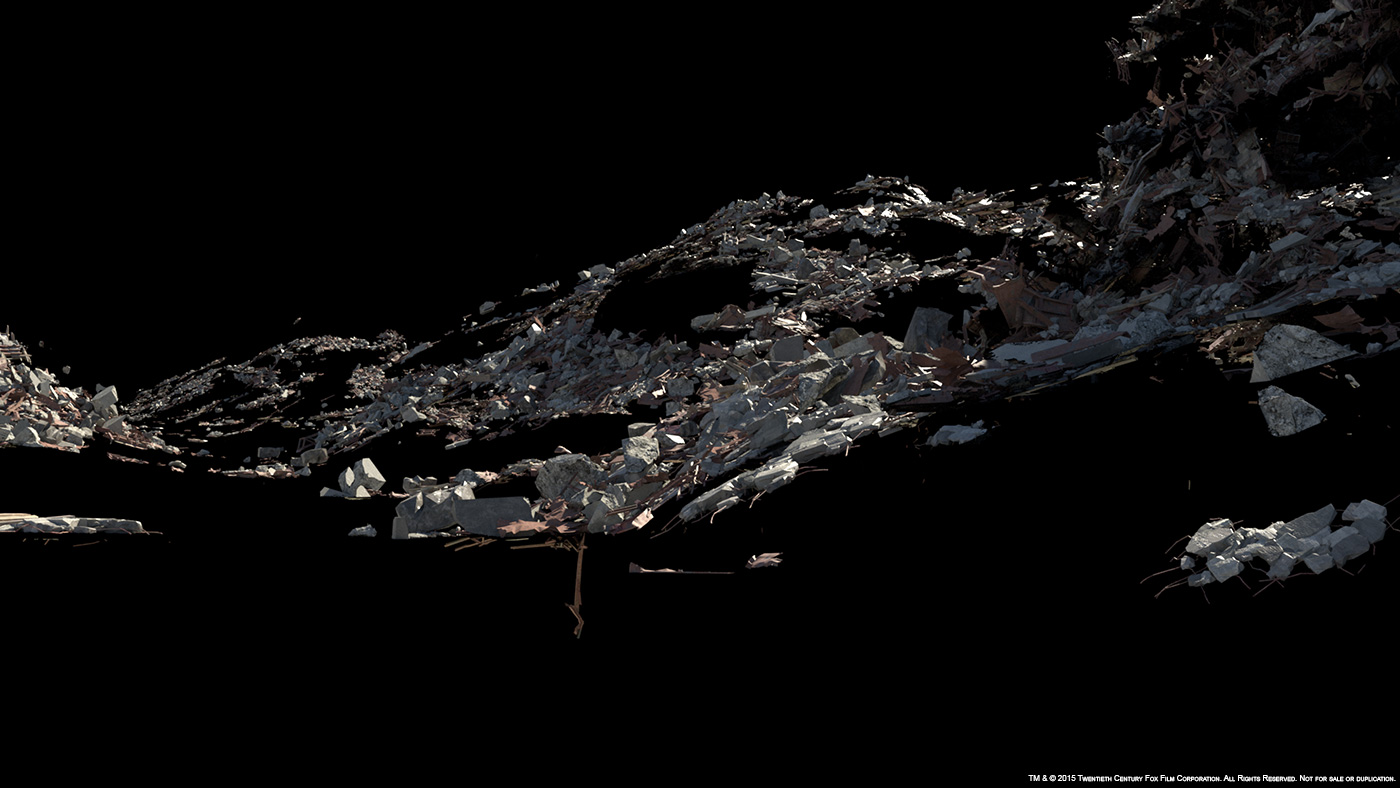

The next step was dressing in details like roof debris, vehicles in the street and signage. The vehicles were placed to look like they were abandoned in a hurry with total traffic disarray. The next step was adding sand dunes that have eaten up the city over time. We hero modeled the main dunes to work with the composition and lead the eye and dressed in surrounding dunes from a library. We then procedurally dressed in building and terrain debris to add scale and procedural weathering to age the city. Finally we added moving elements with flying paper, hanging building rags and moving dust.

What references and indications did you receive about these desolated environments?

We were provided with a collection of concept art at the start of the project which served as a great guide. We were also lucky to have Alan Lee and Michael Pangrazio involved in detailed concepts for key shots.

What is the best way in your opinion to create these kinds of environments?

On this particular project our approach of building the scorch environment entirely in 3D worked well for re-use across shots and allowed the director flexibility to change cameras or lighting. When rendered together the city also benefitted from accurate reflections in the glass and bounce from surrounding buildings. The combination of art directed and procedural damage and debris helped tie everything together.

What was the most complicated environment to create and why?

The opening shot of scorch when the Gladers walk out into the hot sunny sand with the decrepit abandoned city around was a fairly complex shot. It was a slow moving wide angle camera that is the big reveal. You see the entire depth of the street with all its details in this shot. Thankfully it had to be delivered towards the end of the schedule which gave us time to build our library. This shot was the culmination of all the techniques we had developed for this project.

Doing so many elements in CG is a technical challenge for the render space and time. How did you handle it?

Weta’s proprietary renderer Manuka is very powerful when it comes to geometrically heavy environments and is able to render it very efficiently. We also took advantage of Manuka’s instancing support to dress the buildings and terrain with millions of procedural instanced debris with a small impact on the total rendering time.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

We had to deliver 579 shots in a relatively short time and had to put in long hours towards of the project but the director’s encouraging words and seeing the great looking work we were producing kept the morale very high.

What do you keep from this experience?

We got a unique opportunity on this project to really think about a post-apocalyptic environment and design and build it in full 3D. The tools and techniques we developed to achieve this will be useful for future projects.

How long have you worked on this film?

I have been involved with this film since late January. We spent the early weeks understanding the story we were trying to tell with the visual effects, pre-production artwork, design and collecting references.

How many shots have you done?

We delivered 579 shots in total.

What was the size of your team?

We had a strong team of 350 including support.

What is your next project?

ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

BLADE RUNNER, AKIRA, THE FIFTH ELEMENT and GLADIATOR.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Weta Digital: Official website of Weta Digital.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2015