In 2014, Charley Henley explained to us the work of MPC on 300: RISE OF AN EMPIRE. He then worked on CINDERELLA and THE JUNGLE BOOK. ALIEN: COVENANT marks his return to the Alien universe.

How was this new collaboration with director Ridley Scott?

It was an honor and a joy to work with Ridley Scott again. Taking on this job was daunting for me to start with, but once on board with Ridley, his direction is so strong and visual and he is so confident in what he does, he brings the best out of the crew, everyone brings their best game to the table for him.

What was his approach and expectations about the visual effects?

The expectation was that we would bring his vision to life to the very highest standard, but he is also extremely pragmatic. He doesn’t chase pixels or spend time on things the audience won’t notice or appreciate. He taught me to appreciate when the work is good for the film, move on, and not to noodle the shots too much.

He was always also open to new ideas and the whole process was a constant evolution based on the very strong original brief. He likes to get as much in camera as possible and loved the shoot and trickery of filming effects, but also, I think really enjoyed the creative process and opportunity he gets to work with visual effects artists.

What was your feeling to be back in the Alien universe?

I love Science fiction and the use of the latest VFX techniques as a tool to express it. PROMETHEUS was one of my favorite projects to work on, so getting back into the ALIEN universe felt like home.

How did you organize the work with VFX Producer Sona Pak?

Sona and I worked very closely together through out the whole project. She concentrated on schedule and planning, budgeting and crewing and worked closely with the film producers and Fox Studios to make sure we were on budget and that the team were doing the right thing at the right time. She was also a partner on the challenging journey the 18 month project took us on, we would bounce idea’s off of each other and try to keep each other sane when things got a little chaotic! Sona covered much of the logistics and communication, allowing me time to work on how we would produce the images Ridley wanted for the film.

Can you tell us how you choose the various VFX vendors?

Both history and need guided the decisions on which venders we used. Ridley had worked with MPC on many previous projects, in particular PROMETHEUS for which I was MPC’s VFX supervisor as well as THE MARTIAN. There had a been a lot of great digital double and creature work done at MPC on recent projects so there was confidence they should be the lead facility. Framestore had recently worked with Ridley on space for THE MARTIAN, similarly Animal logic now had the original crew who did the holograms for PROMETHEUS. Also as we were shooting in Australia there was good reason and incentives to use Australian based companies and so Luma and Rising Sun came on board.

How did you split the work amongst these vendors?

MPC was lead studio. VFX supervisor Ferran Domenech and his team built and animated the newly designed Neomorphs including their gory births and the growing baby versions as well as the classic Xenomorph creatures. For the landing and exploration of the planet MPC did all exterior environment work, weather enhancements, giant tree’s the CG landing ship, FX water simulations, the dead tree environment around the crashed Juggernaut, the engineers city, the rescue scene and heavy weight CG lifter ship.

During post an unconfirmed scene where David recalls the genocide of the engineers as a flashback was given the green light and MPC London put together a great team who i’d just worked with on THE JUNGLE BOOK, including DFX supervisor Audrey Ferrara, CG supervisor Ben Jones and Compositing supervisor David Griffiths. They took on the challenge and worked with concept artist and film maker Alessandro Bavari to create this standalone scene which involved many full CG shots including the Juggernaught, Mother tug ship, the Engineers city, thousands of Engineers and a huge amount of FX simulations for the pathogen and black goo FX that explodes out of the victims.

The terraforming bay scene where the Xeno gets jettisoned out of the Covenant ship was also MPC’s work with the collaboration of Rising Sun pictures where Adam Paschke headed up a team creating FX smoke simulations.

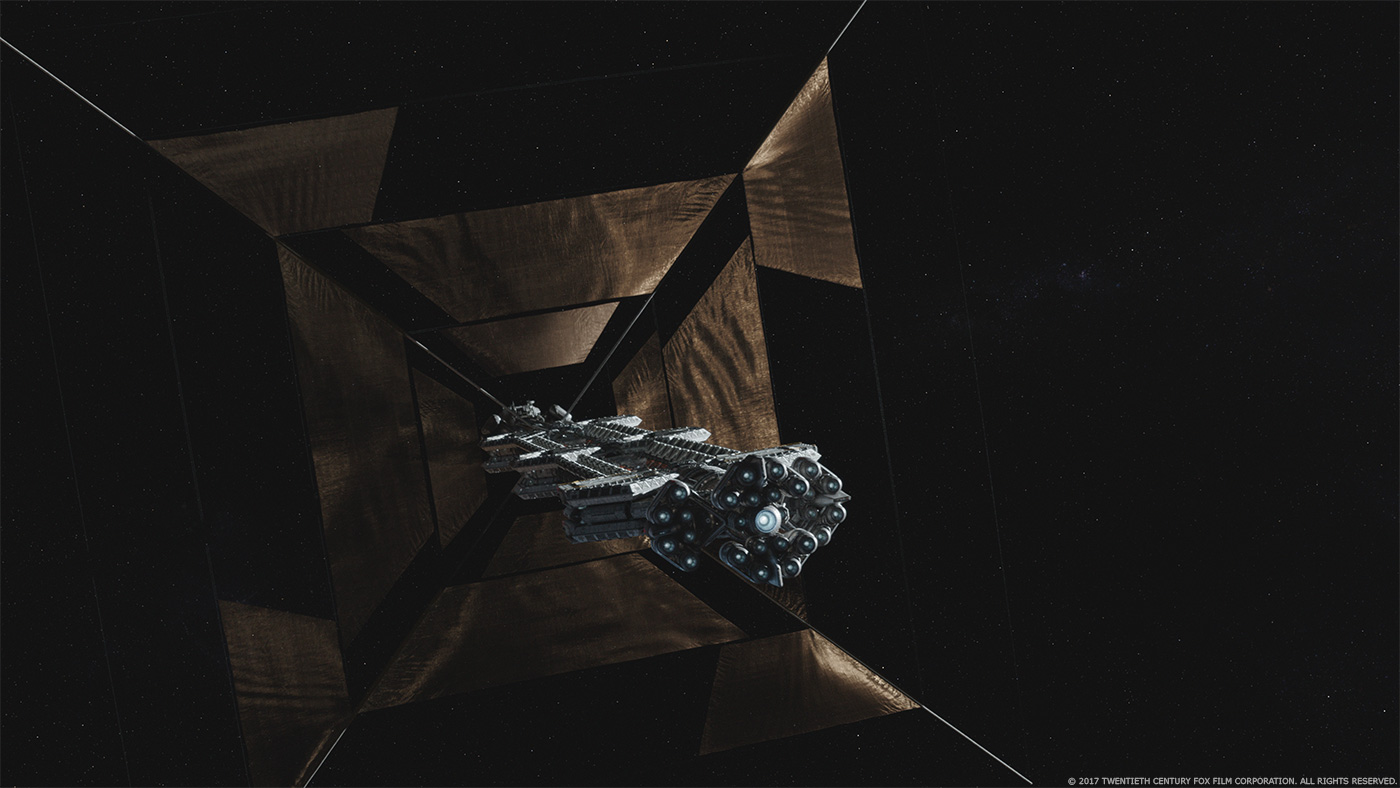

Christian Kaestner supervised the Framestore team in Montreal who had the challenge of building the huge Covenant ship and endowed it with a kilometer square recharge sail or mylar-like material. They also covered space, the planet as seen from space and it’s high altitude cloud storm, as well as recreating the CG chest busting baby Xenomorph. Framestore’s London team headed up by Stuart Penn worked on the classic face hugger moments along with set extensions in the hall of heads and face replacements for the David and Walter fight scenes, where Michael Fassbender played both parts. Paul Round of Peerless and our lead in house compositor Daniel Rickard worked on the challenging, 5-minute long shot where David teaches Walter to play the flute.

VFX supervisor Paul Butterworth and his team at Animal Logic stepped back into the Alien world after Ridley was so happy with similar work they did for PROMETHEUS. They created the holograms and some monitor graphics for the show, they also worked on the white room opening scene as well as a number of set extensions in side the Juggernaut and Shaw as an Engineer recorded hologram and mummified body in David’s lab.

VFX supervisor Richard Bain came on board to support me supervising the volume and he focused on working with our in house team and Luma VFX supervisor Vincent Cirelli and Brandon Seals who’s teams work included the floating lights in Davids lab and the Motes that seed the birth of the Neomorphs by burrowing into a host through and ear or nostril, sleeping pod graphics and corridor set extensions for the interior of on the Covenant. Jim Gibbs’s team at Atomic Fiction looked after the steaming acid wound that inflicts Lope after his face hugger incident.

Can you tell us more about your collaboration with their VFX supervisors?

The project was a creative beast with many design challenges, so I tried to spread the load across the great minds of our VFX Supervisors and keep the process open to their input. With facilities all around the globe, good and constant communication was crucial to keeping up momentum and keeping the work in tune with Ridley’s references and style. Sona set up a review routine; I was based with editorial in London and ran cineSync reviews in the morning with Australia, mid day with London teams and then in the evening used Framestore and MPC’s network to remotely review work with Montreal using Skype and synced RV or TVIPS.

Can you tell us more about the previz process?

Previs and postvis had a role in a number of challenging scenes. Argon and The Third Floor worked up the previs and proof covered the postvis. Ridley used the previs of certain scenes to help set the staging and flesh out idea’s before committing to the shoot. As an example for the Med bay scene, where we witness the eruption of the Neomorph baby from Lewards back, Ridley drew out his own boards for key shots, Jason McDonald of Argon then did a blocking overview of the action which was reviewed and refined with Ridley. The next stage was to mocap some performances and get a rough cut of the shots in order. Ridley reviewed again and was inspired to draw up some more boards and rearrange the action, which is some cases meant script revisions. We refined the edit along the way and worked out details, like out how big the creatures should be as it grows over the scene. We ended up with a cut sequence of animatics that evolved the story and was used it as a guide to for shoot planning.

Can you explain your work on the opening sequence and especially the big view outside?

Production designer Chris Seagers built a simple white room with one wall as window on to a majestic landscape. Ridley wanted something quite moody but beautiful, we were inspired by the aerial photography of Iceland that we had shot for PROMETHEUS; and so this became the bases of a large 180 degrees matt painting with simulated water and birds that Animal Logic produced and composited into a blue screen set shot on the stage at Fox studios Sydney.

How did you work with the art department for the Covenant?

Chris Seagers and I spent a lot of time together finding an approach to building and shooting the world Ridley was conceptualising. We studied every set and scene, working out how VFX would support the builds. I was keen to have at least part practical builds for the ships and exterior sets and VFX helped out on some of the larger interior sets like extending the long corridors of the covenant ship and topping up the huge head statues in the hall of head. We also worked together with concept artist including Steve Burg who designed the ships and MPC’s team in LA. After the shoot we had Steve role over to support the VFX team so we had continuity in the designs that kept evolving through postproduction.

Can you explain in detail about the creation of the new spaceship?

We had three ships to create for the film. The kilometer long interstellar colonising ship, the Covenant. And slung below are two drop ships; for transporting crew, the Lander; and for heavy weight lifting, the Lifter.

The art department worked up blueprints and concepts for each of the ships, for practical build reasons, which I think also serve to make the designs more believable, both the lander and lifter share the same floor plan and use the same thruster technology.

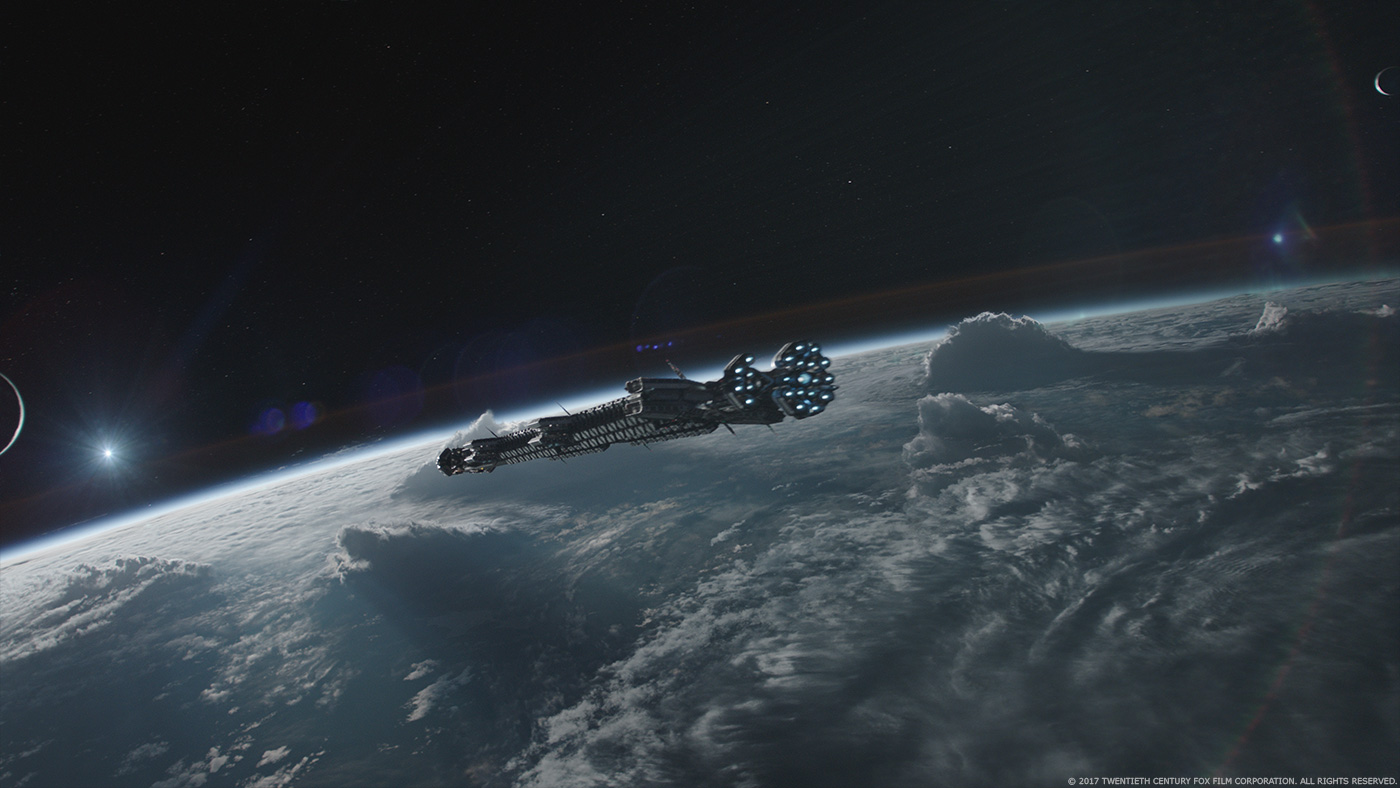

The Covenant had some small set pieces built for real for the astronauts, Tennessee and Ankor to interact with on the space walk shoot, shot against black screens. These set pieces also gave Framestore some key texture references to help build the rest of the huge ship. Framestore used a modular system to instance tens of thousands of individual sections giving great detail and scale to the ship. We designed in imperfections to help avoid a perfect straight CG edge. Ridley also wanted the ship to have flex so when it’s flying through a high altitude storm the ship twists and bends. 18,000 lights and retractable antenna where added along with interior cockpit detailing and thruster FX.

The lander and lifter also had a partial practical build. The interiors were all built as set pieces with the cockpits mounted to a gimbal that SPX supervisor Neil Corbould rigged to give a proper turbulent ride to the actors and camera crew, out the window we used black screens and SPX smoke and water to get shots in camera for the interior storm moments and green screen for the exterior planet shots. Fully CG exterior versions of both ships were created by MPC and shared with Framestore for the space shots. One engine and a door and ramp of the Lander where constructed on location in New Zealand’s southern Fiordland to shoot the crew exiting the ship and give Neil’s team something to blow up. These real set pieces were shot as texture reference for MPC asset team to build CG, led by Dan Zelcs. The same was true for the lifter; We built a quarter of the floorplan for real a cab and one engine. This was a good size to mount to a gimbal and allowed for maximum maneuverability. It gave a real surface for the actors and Ridley to shoot on and a great reference to lock MPC’s CG build into a photo real look. Both ships had maneuverable thrusters based on the harrier jump jets. Ferrans’ team at MPC animated the engines and ship with the finesse of a fine pilot and when Ridley wanted the lifter to feel unwieldy in it’s weight we designed in a lot of oversteer so it feels like Tennessee is having to control something like a huge lorry sliding on ice.

How was filming the beautiful arrival of the ship on the planet?

Ridley chose a very beautiful but logistically challenging location for the landing scene. On a recce he had found some black and white postcards picturing the Fiordlands in New Zealand in extreme weather and said “that’s it, that’s the reference for the planet”. So we went on a shoot there. The weather was often very wet which did not make shooting easy, and to make things harder he chose to have the lander land on the waters edge, in a tidal zone. We had to help make the weather bad and the tide consistent in post. We also enhanced the landscapes by adding waterfalls and giant trees and removing any sign of sunlight. David Bowman who worked with me on PROMETHEUS was brought on to help supervise the second and plate unit shoots, this included a helicopter shoot we needed for the landing scene. We set him up with a shotover hydra aerial camera system, it’s a six camera array, to stake out the fiordlands waiting for perfectly bad weather that wasn’t to dangerous to fly in. The stunning super wide ultra hi-res panos produced meant we could find the correct area on the frame and angle to use of window comps in post. It also allowed Ridley to design camera pan and tilts in the edit. In the end the wide undistorted stitched panos looked so good we used many of them as they were.

The team discovers many beautiful locations. How was enhanced these various places?

Giant CG trees and more rain. Sometimes on the shoot we couldn’t afford to wait for the best bad weather so we’d send Dave back when the weather was really bad to reshoot the backgrounds from the same camera positions as the main unit shots. Although we used locations where possible the decimated hill where the Juggernaut has crashed was a CG build based on a back lot set, also when the crew arrive at the city the environment is CG based on references taken in New Zealand.

David meets his “brother” Walter. How did you manage the various interactions between these two Michael Fassbender?

It took a few different techniques; the principle was to have a very good double for Michael, who matched his physical performance and could play both parts well. The basic method was to shoot them one way and then reverse the roles, shoot again and do a split screen comp. For action scenes like the fight we did face replacements and for more complex situations used motion control.

Which shot was the most complicated to do with them and how did you achieve it?

The hardest was a slow scene where David teaches Walter to play the flute. This involved a lot of interaction; we went for a motion control solution where the idea was to have a number of cuts and one hero shot motion control to introduce the scene. On the day Ridley wanted to set up the whole scene in one motion control shot lasting 5 minutes, this certainly added to the challenge as testing timings and doing any retakes became long and challenging. Fundamentally once we had a hero take for David we did many iterations for Walter with the same recorded camera move and a clean pass without actors, we used the Technodolly, run by our tech operator Ron Tatham, it’s set-up like a standard crane rather than a heavy motion-control rig and it gave Ridley and our DOP Dariusz Wolski the flexibility to set the move as they would with a normal crane. It was a real challenge of patience to seamlessly stitch the plates together.

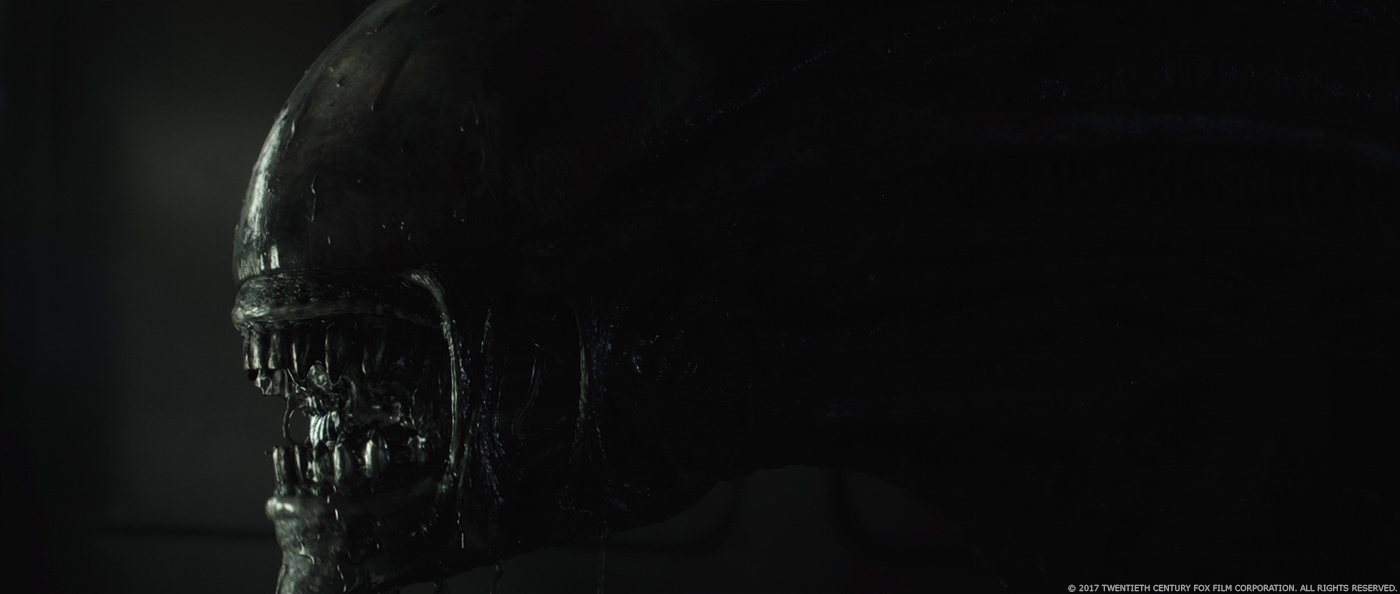

The movie is introducing a new creature, the Neomorph and the return of the Xenomorph in all it’s glory. Can you tell us more about their design and creation?

There was a lot of history to live up to with these creatures so going CG on them was a daunting decision, but for this film Ridley wanted so much performance out of them that it was a decision made early on. Having said that we took a very practical approach to designing and had practical creatures to work with on set. Conor O’Sullivan worked closely with me to decide what was needed on set and what we could shoot practically and what would be CG in the end. Ridley wanted to shoot practical versions even if they were to be replaced but in some shots the practical is used.

From the outset Ridley had a lot of concepts and references at hand for what these creatures should be like. The Xenomorph was to reference a few favorite H.R Giger designs but also be a little less biomechanical and more organic in a direction heavily influenced by écorché’ anatomical sculptures found in Museo della Specola in Florence Italy.

The designs started with concepts drawn up with MPC’s art department, where then picked up by the practical creature team for the shoot period and then further refined in post through zBrush sculpts and look development in Renderman.

Did you receive specific indications and references for their animation from Ridley Scott?

Nailing the animation of the creatures was one of the biggest hurdles. We went through many many tests before we found a character and motion to the creature that was not too terrestrial but also not too fantastical. At one point in a review with Ridley we had a breakthrough. It was a shot of the baby Neomorph, hand animated by MPC, running away through the tall grass after having burst out of Hallets mouth. Ridley saw it, jumped out of his seat and took a picture of the screen with his phone. He suggested we print that frame out as a reference for all the animators. The pose mid run captures the disturbing character of the Neomorph. It’s body was compressed, loosing the neck and it’s limbs where stretched out and slightly distorted. It was a good clue and things started rolling from then on. Ridley also had us look at Goblin sharks for the Neomorph, their jaw can dislocate and be thrown forward. Together we also researched a lot of natural creatures from Baboons for their aggressive and assertive behavior to the way insects, like the praying mantis, move and attack.

How was their presence simulated on-set and especially for the Neomorph?

We used a collection of practical versions of the creature on set, we had stunt men in grey suits that could block the action and interact with the actors. But also Ridley was keen to have practical creature’s to shoot and light against, so Conor built a family of monsters including an 8 foot Xenomorph, with a puppeteer system inspired by bunraku Japanese puppets. The creature was quite intimidating to have around on set. For both the Xenomorph and Neomorphs we also had creature suits so Ridley could stage the action, and the actors had an acting creature to play against. This was particularly successful in the scene where the Neomorph meets David.

Which sequence was the most complicated to created and why?

The Lifter rescue scene was very complex to achieve as the scale was beyond anything we could build for real. Set in the plaza of the Engineers city, MPC had to build a huge digital environment; including sky and mountains, the Engineers city and a plaza covered in hundreds of thousands of petrified engineer bodies, also the lifter ship itself, digital doubles and a Xenomorph.

To make sure we filmed everything we could for the scene required a lot of planning. Ridley did his own storyboards and worked closely with Jason McDonald at Argon to previs the scene. Chris Seagers made cardboard models of the sets and 3D prints of the ships so we could plot out the geography and look at the lighting situations in miniature during preproduction meetings.

To achieve the shoot we built three separate set pieces, all outdoors. There was a piece ground about 100m square littered with 100 dead engineers, A small section, about a tenth, of the cathedrals giant staircase and a quarter section of the lifter ship mounted onto the six-axis gimbal and surrounded by bluescreen.

We modeled the SPX gimbal and the part set build in Maya and plotted the sun path. We then used this to work out with Dariousz the best location and angle for bluescreens and positions for the set. After the shoot we did a lot of temps and postvis to nail the scene for turnover to MPC who then tracked and layed out the practical based shots, created over a dozen fully CG shots, animated the ship, digi-doubles and Xenomorph and added a huge quantity of simulated FX including the destruction of petrified engineer bodies that disintegrate into clouds of dust as the ships thrusters blast the ground.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

Finding the right motion for the creatures. It’s something you really want to nail before you start shooting but they kept evolving and it was half way through post before we had settled on the style.

What was the main challenge on this show and how did you achieve it?

For me the biggest challenge was the sheer scale, complexity and variety of VFX pieces that needed resolving from shooting where every day was a new challenge to post where the design process with Ridley just kept going. Every trick in the book was called on to pull off the project. It keeps it very interesting but also it keeps you on your toes because you have to keep a lot of plates spinning. Thankfully we had such great teams who were so passionate about the project that once they had a good brief great work was constantly being produced. Really the crew solved most of the problems for me, so it turned out fine.

What is your best memory on this show?

Roughing it on location in New Zealand; with the rain pissing down, wearing fishing waders because of the ever-changing tide, sitting in a video tent with Ridley Scott shooting the landing scene and have him draw me the shots he wanted for the Covenant space walk. It’s now long enough ago I forgot how tough it was and remember it like a great adventure.

How long have you worked on this show?

Around 18 months.

What’s the VFX shots count?

Over 1440.

What was the size of your team?

More than 1200 people worked on the VFX for the project.

What is your next project?

TBC!

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

MPC: Dedicated page about ALIEN: COVENANT on MPC website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2017