Simon Jung has been working at Weta FX for almost 20 years. He has worked on many films such as District 9, Avatar, The Hobbit trilogy and The Tomorrow War.

In 2022, Dennis Yoo told us about the work of Weta FX on The Batman.

How did you and Weta FX get involved on this series?

Simon: David Conley, our Executive VFX Producer here at Weta FX, is a huge fan of the game and he made it happen.

What was your feeling to enter into the world of The Last of Us?

Simon: It was surreal. Getting a chance to be part of re-imagining such an iconic franchise for a different medium was exhilarating!

Have you played the original video games?

Simon: Hell yeah!

How was the collaboration the showrunners, the directors and VFX Supervisor Alex Wang?

Simon: Working with Alex Wang was great. He was our main point of contact and we had reviews pretty much daily. He has an excellent eye and because of his background as a VFX artist, we spoke the same language. We had a lot of wiggle room creatively and it was a really collaborative process trying to find the best possible visual results together.

What were their expectations and approach about the visual effects?

Simon: For Craig Mazin, the main thing was to have everything grounded firmly in reality. No excessive gore or anything fantastical or supernatural. That was perfect for us as we knew that if we got the physics like weight right, and if the CG was integrated into the plates in a believable way lighting- wise, he would be generally happy with it. Alex was keen to push the creature work as physically correct and as photo realistic as possible which is completely in line with our own philosophy.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

Simon: We worked very closely with the various internal departments at Weta to ensure that the multiple episodic delivery dates were achieved. This often involved liaising with other shows in the facility to make sure that each project’s priorities were met. The client was accommodating and understanding with this, trusting that Weta would complete the work.

What was the work made by Weta FX?

Simon: We delivered a broad range of VFX work, from set extensions, weathering, and ageing of existing plates to creating fully CG environments. Creature work included Clickers, the Infected we see in Faneuil Hall, and the battle scene in episode five, as well as the monkeys in the university campus and lab, the deer that Ellie shoots, and the giraffes in the final episode.

What was your approach about the Clickers and their variations?

Simon: ClearAngle delivered scans to us of the Clickers we see in The Bostonian Museum and we built those to a hero level to be able to use them for the shots in that environment where they were either all digital or a partial replacement like the Clicker that gets shot in the head, for example. All other Clickers that we see in the battle are variants of those two original ones. From those we generated gender, ethnicity, wardrobe, cordyceps growth, scale and shading variants.

On top of those, we had scans of multiple Infected that were also built to a hero level, which meant we could simulate their tissue, muscles, clothing and hair. They helped flesh out some of the shots in the battle scene and were also used for the first wave of Infected that burst out of the sinkhole. For the big wide shots in the battle and at Faneuil Hall, we also made crowd elements of additional, single mesh Infected for our Massive simulations, which were used further away from camera.

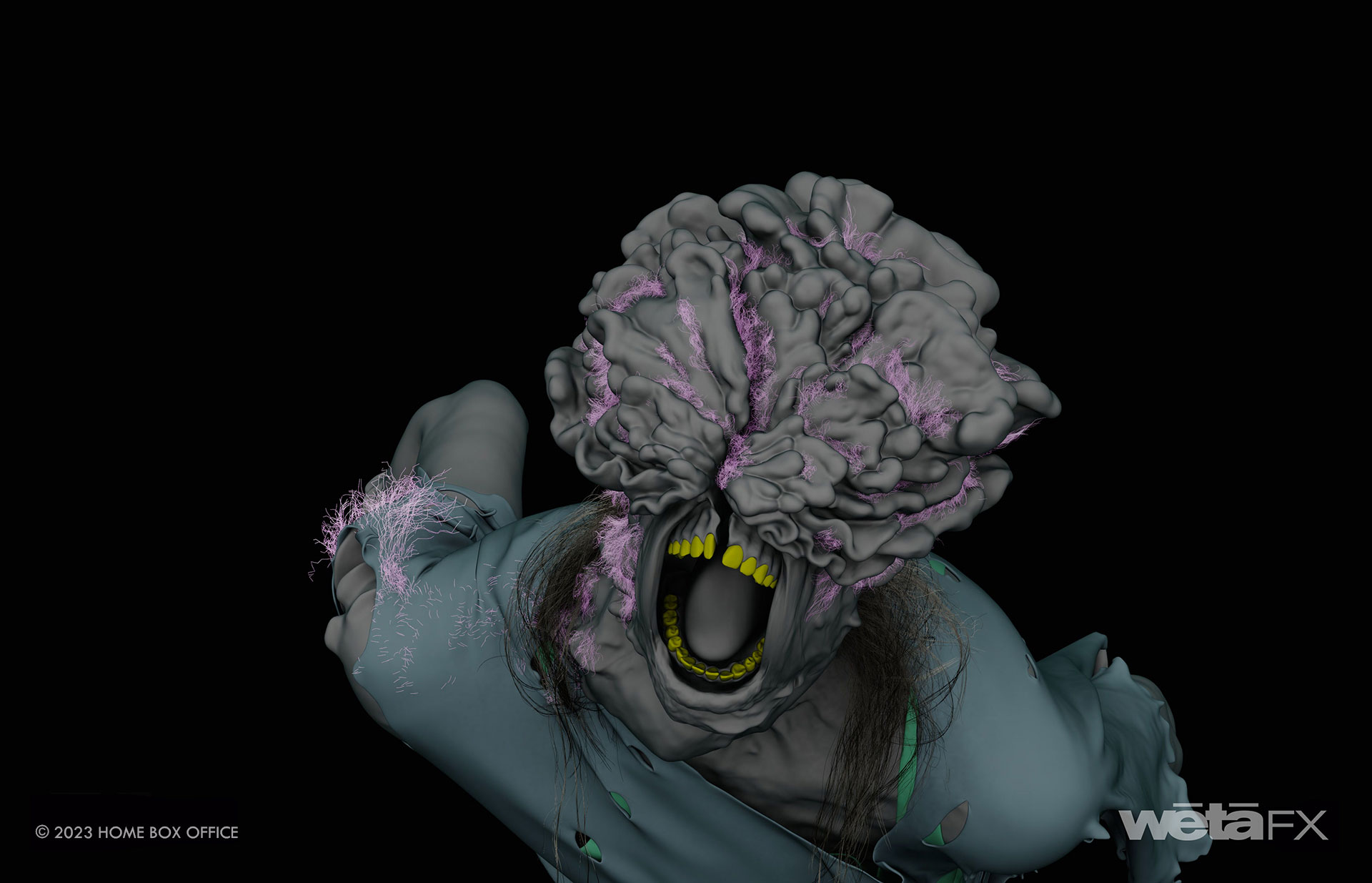

Can you elaborate about the child Clicker?

Simon: The child Clicker was one of the creatures that took the longest to get right. We started off with an incredibly creepy concept piece from one of the artists at Naughty Dog, which we immediately fell in love with. They also provided us with a concept model. One of the biggest challenges we had was to make it clear she was a child, when we had very limited visibility of her facial features due to the giant cordyceps growth that is typical for fully matured Clickers. We only had the cheeks, jawline, and mouth available to show that we’re looking at what used to be a very young girl. The pigtails helped and added an extra element of creepiness to the character. The result in the end was truly horrifying and equally sad!

Initially we had planned to only do a head replacement in the shots that take place in the car, but because the proportions of the body had changed so drastically for the shots where she jumps on and takes down Kathleen at the end of the sequence, we decided to replace her wholesale in the car as well. We match-moved the amazing body performance by the girl that played her and applied that to the digital double of her.

Can you tell us more about the cordyceps look?

Simon: The cordyceps outside and inside the Bostonian Museum are dead, while at the Faneuil Hall environment they are alive and thriving, so we had to come up with two different looks. We added a second skin layer to the dead variant to give it a slightly peeled look and added a fuzz layer in the crevices, which was essentially a fur set. All of that made for very heavy geometry and we ran right up to the limit of what our machines could handle.

One of the hardest things to get right was the flow and the scale of the cordyceps shapes. Especially in the wider shots we needed to find the balance between not miniaturising the environment by making the shapes too big and the shapes turning into visual noise by making them too small. For the wider shots we arranged the smaller shapes in a way that they mimicked the distinct contours of a single cordyceps shape.

We built a library of shapes that we could place through Layout in cases where we just needed to supplement the existing practical ones, like inside of the museum, for example, which had been dressed beautifully by the onset art department. The cordyceps that covers the facade as well as all the shapes in the Faneuil Hall environment were bespoke hero models that were hand placed.

How did you manage the impressive crowd shots?

Dennis: We used motion capture heavily for our crowd motion, but the crowds were a mixture of live action, animation keyframing, motion editing, and “Massive” simulation, depending on the shot. As an example, for the shot where we first see our hoard of Infected pouring out of the pit, we initially did some postvis motion studies where we quickly captured the motion of a number of different performances, so we could find the right feeling and tempo. Craig decided that the Infected needed an inhuman type of feeling, so no matter how fast I got our stunt performers to move, it was never fast enough. In the end, we sped up our CG motion by 8% in order to give the motion that eerie, inhuman feeling without totally breaking the physics of things.

Another example of our crowd work is the wide shot of Joel’s POV inside the sniper window. Half of the Infected in this shot were live action and the other half were Massive simulations. One of our Massive artists, Geoff Tobin, gathered a library of motion which he fed with simulated creatures that react to forces and goal oriented tasks. In this shot, Geoff orchestrated a series of actions by stringing together multiple performances where several different actions are triggered in sequence. So a single creature agent would have a combination of actions such as climbing, running, getting shot, and dying that are triggered when goals are met. With hundreds of simulated agents simultaneously reacting to each other and rolling through the triggered actions, this organically orchestrated crowd virtually becomes alive.

Can you elaborates about the creation and animation of the Bloater?

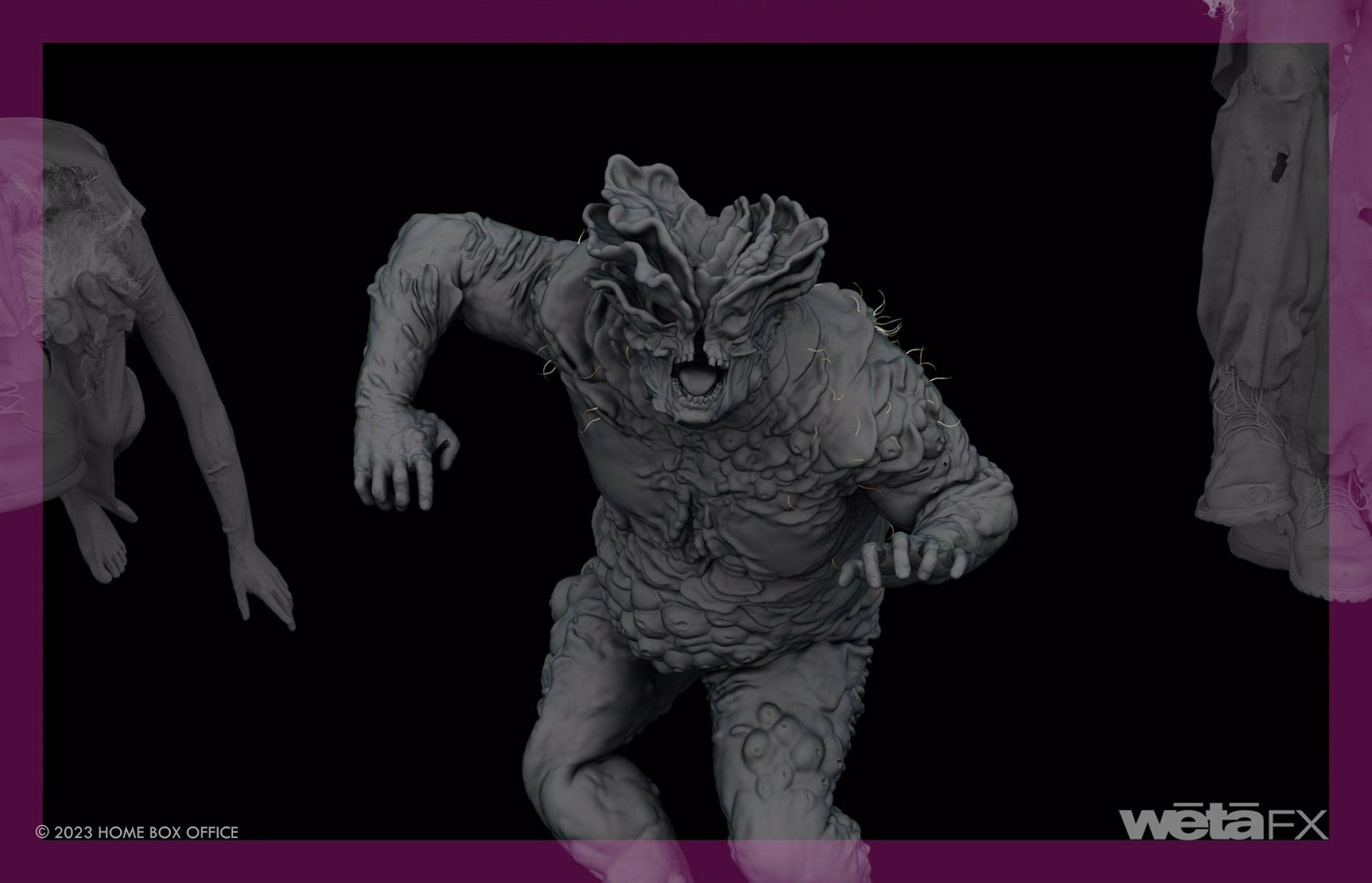

Simon: Initially the Bloater was a stuntman in a prosthetic suit, and it looked great actually! The reason why we went all CG with the character was because we wanted to free up the performance. Knowing that we were going to replace him opened up the design too, as we weren’t bound by the physical constraints of a suit anymore. It allowed us to change proportions, scale and materials. Like the Clickers, we started off with the original scan of the Bloater. Based on that, we did concept work and received additional artwork from Neil Druckmann’s team to help inform the overall height of the character, including the length of his limbs, so we could make him look stronger and more menacing. We also redesigned the head of the Bloater by adding bigger cordyceps shapes and giving him the caved in face, which wouldn’t have been possible with the prosthetic suit.

Dennis: There were definitely some evolutionary changes to our Bloater. Like Simon mentioned, we worked at first with the scanned prosthetic bloater suit, which was designed to look heavily asymmetrical. Originally the Bloater had one leg that was much thicker and wider, like a monstrous elephant foot. When a biped is asymmetrical in that way, their movement must also be adjusted to fit the physics of its anatomy. Unfortunately, we are all hardwired to read an asymmetrical bipedal motion as injured or weak – neither of which were traits we wanted for our Bloater. In the end, the new design was more symmetrical in nature and the Bloater’s performances were recaptured to match its new look.

What was the main challenge with the Bloater?

Simon: One of the biggest challenges was giving him the weight and gravitas required for such an iconic character.

Dennis: Finding that performance was my biggest concern. We initially had Ike Hamon, our resident Mocap performer, try and act out a series of performance tests on postvis shots. This meant grabbing filmed plates and throwing our CG Bloater in as a rudimentary first look. These types of studies help tremendously, as they become a starting point for discussions with Alex Wang, the production VFX Supervisor, and the showrunners Craig and Neil on what the final outcome might be. We also collected a series of clips of game play of the Bloater and strung them up alongside a rough version of our motion. Although the game play motion is rudimentary, this is the actual Bloater that fans remember so we wanted to stay as true to that as possible, while making it as real as possible.

The battle in Episode 5 is seen at night. How does that affect your work?

Simon: Other than needing to make shading adjustments to the CG characters so they don’t lose all colour contrast from the red firelight, it didn’t affect our work too drastically. We had replicated the lighting of the scene accurately based on onset data and limited beauty lighting to the hero moments like the emergence of the Bloater, Perry being torn apart, or the child clicker in the car, for example.

What kind of references did you receive for the animations of the Clickers and the Bloater?

Dennis: We had a motion capture (faux cap) shoot onsite of the cul-de-sac set after primary shooting. “Faux cap” is a proprietary way we capture motion by setting up several synced witness cameras to create a volume that triangulates 3D space of the actors wearing the “faux cap” suits. Unfortunately we had to film at night, which created long shadows that didn’t help the capture process. In the end, we used the footage from the witness cameras as our initial reference, but as the post production developed further, so did the performances to match what was needed for the shots. There became an emphasis to find the essence of what these creatures are, which is entirely in the game. Luckily for us there is a lot of content of the game online. It goes to show how well received these games truly are, as the fan base content creation is quite extensive. There are Fan created clips and edited compilations of all the Bloater motion and clickers motion in its entirety. We scoured the internet and collected several of these and used them as reference in order to create what we see in the final performances.

How did you add weight and menace to the Bloater?

Dennis: We used motion capture extensively to get the base of our performances. I’d like to point out that there is a misconception with motion capture that performances can be sub-par because in the end it will be CGI. The problem is when a performer looks like they are pretending to be something, that’s exactly what it ends up looking like. Pretend! So when capturing motion for our final performances, we had Ike Hamon wear a weighted chest vest and Velcro weights on his arms and legs to add literal weight to his performance. There was a fine balance as to how much weight he would wear as if he was too encumbered, that’s exactly what it looked like. From there we would use that motion capture as the base of the motion and keyframe on top. Sometimes the motion was entirely keyframed in the end, but in all the shots with the bloater there was always a base of Mocap.

Can you explain in detail about your work on the animals in the zoo?

Simon: The shots of the giraffes in Salt Lake City are a mixture of live action, full CG and partial replacement. Because these shots cut back-to-back, we had to ensure that our CG asset matches exactly to the live action giraffe not just looks-wise, but behaviourally as well. Giraffes have very distinct chewing motion and very long tongues, for example.

Dennis: The main thing we did was gather as much reference footage as we could of live giraffes in order to study their actions. We visited our friends at the Wellington Zoo, where they have 3 beautiful giraffes in their enclosure. That visit was invaluable and I want to personally thank Wellington Zoo for being so accommodating to us once again. We also had the footage from the shoot and used that to create a “Pepsi challenge” where we put our CGI giraffe alongside the real one in the footage and mimic it the best we could. Even though we knew those particular shots would be full live action giraffe, it gave us insight into how our giraffe Naboo had her own unique ways of doing things. Our Facial Animation and Modelling team did a brilliant job working together to create lifelike facial expressions and motions. The body motion was a bit tricky as we couldn’t just go out and motion capture giraffes. Also, hoofed animals are notoriously difficult to keyframe mainly due to the way they pillar their legs to hold their weight. We did do a bit of keyframe work, but the main bulk of the motion was from our Motion Editors. Giraffes, although similar in many ways to horses, move quite differently and have their own unique cadence to their walks, canters, and runs. Our Motion Editors used our horse mocap data from our motion library as a base, and painstakingly edited it to fit with what a giraffe would move like.

Can you elaborate about your environment work?

Simon: We approached the environment work different depending on what was needed. The Faneuil Hall environment was all digital, as were most of the set extensions around The Bostonian Museum. We also had a fully renderable version of the cul-de-sac where the battle took place because we had to change the camera angle in the big wide shot – it rises to give us an overview and makes it clear that the Infected have won the battle. In the Salt Lake City environment, we stitched together multiple drone footage takes for the deeper city background, projected that onto geometry, and added destruction and weathering to the buildings with more traditional DMP and compositing techniques. For the baseball park in the foreground, including all the dressing, we built renderable assets and went fully CG so we had control over the lighting and layout of it all.

Which shot or sequence was the most challenging?

Simon: All shots and sequences had their own challenges – in some cases it was about volume, in others it was related to design. Some of the work was hard but all of it was fun!

What is your favourite shot or sequence?

Simon: I honestly don’t think about individual sequences or shots too much but look at it more as an overall body of work. Having said that though, the battle sequence is something quite special because so much work went into it and I think it looked incredible in the end!

What is your best memory on this show?

Simon: Our team! They took on this challenge and everybody went above and beyond to get the best possible result out of whatever task was assigned to them. It never fails to amaze me what a group of people can achieve if everybody is pulling on the same string and we had some incredible talent pulling on that one!

How long have you worked on this show?

Simon: All up, including the time we had on set, it was close to 12 months.

What’s the VFX shots count?

Simon: Weta FX delivered a total of 434 shots.

What was the size of your team?

Simon: We had 294 artists and of course our production crew, department managers, facility crew, etc.

What is your next project?

Simon: I’m not sure yet – watch this space!

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Weta FX: Dedicated page about The Last of Us on Weta FX website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2023