Oliver Atherton began his career in visual effects in 2002 at DNEG. He works on many films like KICK ASS, MAN OF STEEL, INTERSTELLAR and HOSTILES.

How did you get involved in this show?

I flew out to meet David Michôd (director) and Andrew Jackson (DNEG Overall VFX Supervisor) in Budapest while finishing VFX work on ‘Bad Times at the El Royale’ and spent a week getting a feel for the Agincourt set and talking through some ideas for the work. From there it was then a case of waiting for the turnover to come while delivering the rest of my current show. Things lined up nicely.

How was the collaboration with director David Michôd and Overall VFX Supervisor Andrew Jackson?

Andrew was based out of Sydney for the start of post where he worked on producing post-vis for quite a large number of the shots in the show. Since he had been involved in the project from the very start he knew the DNA of the shots and understood exactly what David wanted to see. This allowed for swift feedback on things from David while providing our team in Vancouver with some good context and an overall idea of the desired look for many of the environment-based shots. This was a good initial starting point for much of the work and helped shortcut some of the back and forth you can get with signing off creative looks early on in a show. He made sure that the broad strokes were mostly all in place before he had to step away onto another project.

Once we got into finishing shots, Paul Butterworth came on board. He was a wonderful collaborator to work with and really helped us push everything across the line in the final few months. We spoke with Paul almost every day and while we had a couple of meetings with David during the review process to go over some key shots, most of the stuff was filtered through Paul. He has a very good eye for just about everything artistic and really understood what David and Netflix wanted.

What were their expectations and approach to the visual effects?

Due to the nature of the project we wanted to keep everything as realistic as possible by using element plates and avoiding leaning on CG renders too much. Thousands of frames of elements were shot for most of the scenes as well as a huge amount of on-set stills for photogrammetry, and reference for modeling and texturing. David did not want anything to stand out and detract from the story. Everything had to be totally seamless. We received hours and hours of extra footage from multiple cameras that ran just for elements during the main takes. A large part of the start of the show was spent just looking through this to see if anything was going to be useful for our shots as we started blocking them out.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

Many of the element plates for the soldiers were shot towards the end of the day, which meant that the lighting direction and quality was significantly different from the principal photography, and the lenses and angles had too much of a difference to be really useful. The knights’ reflective armor meant that any lighting mismatch was immediately obvious once in shots, and generally they lacked any of the reflection or occlusion that you would expect to see on armor in a tightly packed battlefield. I was worried all of this would immediately stand out when we tried to integrate it into the main plates and we would have burned up a lot of time trying to fix it. Since the initial delivery schedule was fairly tight we came up with another approach.

We decided it would be more cost effective and allow for greater creative flexibility overall to use our budget to push CG assets initially intended for background use to a much higher level than originally planned, which would then allow them to hold up fairly close to camera. This meant we could then reuse these assets across most of the shots allowing us to get through a larger volume of work to an overall higher level of finish because we could fully control the lighting to match each shot.

Sara Emack was my VFX producer on the project and she was great at helping work through all of this so that it made sense for both the budget and the schedule. We had to be fairly careful in how we presented this because introducing CG can open its own can of worms when it comes to creative notes, so we started to test internally how closely our CG knights, horses and boats would hold up in shots before they broke or stood out. We then started showing comps with a mix of CG and elements in frame and then went from there. Ultimately it worked out well and got to the point where the Director was very excited by what he saw could be achieved in some of the larger shots. As the show progressed, and everyone became comfortable with the work, we used more and more of the CG assets, to the point where we have CG soldiers and horses really close to camera in many shots.

How did you split the work between the DNEG offices?

Mostly by sequence. Some of the larger battle scenes had to be split as well, which did start to get a bit confusing as the edit shuffled around. For shared sequences we would identify hero shots and then, once a creative look was locked down, the other team would match towards that. This allowed us to get faster turnarounds on creative notes on the hero shot while still allowing us to push through a large volume of work remotely. We then divided up some of the bigger more time consuming shots to balance out the workload so that we didn’t overload either team.

Can you elaborate in detail on the boats armada creation?

All of the plates were shot at sea which immediately meant that the lighting and camera motion was accurate as opposed to having to lift these off a green screen on a sound stage. That went a long way to giving the final images the natural look that they have. An element of a medieval cog was shot at sea in different positions which gave us a starting point for scale and movement reference as well as an idea of how complex the sails and rigging movement is. We also used this element as one of the closer hero boats in a couple of shots and just replaced the crew on the deck. We built out the rest of the fleet with CG assets including one that perfectly matched the hero element so that we could swap it out as needed. Researching Henry’s fleet revealed that the majority were for carrying cargo which gave them these characteristically deep hulls that you see in our final shots. They also tended to rebuild a ship on top of the frame of an old one as it was cheaper and faster. All this produced some really unique shapes that we could build into our assets to give the scene some variety and flavour.

Ultimately we decided on about five hero ships that would be built to play closer to frame and then the rest were created at a lower level of detail from these asset varieties that would be used to litter the mid and background to give the fleet a sense of scale going all the way off into the distance. We laid out the hero boats by hand to control the main composition. The background layers were then populated with an FX scatter. Our hero boats all had some complex rigging and sail simulation passes specific to their movement to match the practical reference. We also built an ocean simulation to be used for the water interaction of the closer boats that would give us the wakes and also create some of the natural reflections back into the water. Once we dressed all the boats in to the shot we realised that there was a huge amount of interaction on the ocean missing in terms of occluded light, reflections and even in the way the water reacts to the boats hulls, so we ended up mixing in quite a significant amount of CG ocean to make sure they felt integrated. Each boat also needed to have a sense that it was carrying this vast army over to invade Harfleur so we had to dress the decks with our CG armies and carefully adjust them to make sure that you can read them in every shot. This is all then finished off with the usual long days and nights of painful edge work to make sure that we preserved the original quality of the plates – but something subtle that in the end makes it all look that much better.

How did you enhance the catapults?

The catapults were actually practical. The production had built these large scale catapults and fired live projectiles on camera. Unfortunately the projectiles really didn’t travel very far so the work was taking over the fireballs in some of the shots or creating fireballs in others, but it was great to have something physical to work from and a starting point for reference of how the fireballs would look. It was also a great lighting reference for some of the wider shots where you see the camp illuminated by the fireballs as they are launched into the evening sky, which we then matched in our CG tents and camps.

Can you tell us more about the FX work and the castle damages?

We first built the castle as a 3D asset based on references from Carcassonne. Across the sequence the castle had to go through different stages of damage, so we built different versions for each of the stages. These were sculpted in Zbrush for details, and then painted in Mari. An extra pass of DMP was then done per shot to add extra details and more realism.

Regarding the FX work, our FX team, lead by Lisa Nolan, created the trebuchet fireballs based on plate reference the client provided. On some shots we had to extend their trajectory, transitioning from the real fireballs into our CG ones. Other shots were using full CG fireballs. The team also created debris and dust falling off the castle after each hit. The base of the castle was augmented with CG trees so they could catch on fire after the impacts and this also allowed any burning debris and dust to scatter over the tree. The FX team also created burning smoke coming from different parts of the castle.

Comp then came in and balanced all of the elements out. One of the issues on these plates was matching the qualities of the very characteristic old lenses used on this film which had some fairly unique properties. Our comp team had to create bespoke lens profiles from scratch to ensure that the elements would sit into the original plates properly. Blending the CG fireballs with the practical ones was also quite a challenge and involved lots of warping trajectories and trails into place. The actual impact of the mortars on the castle wall was supplemented with lots of practical elements. Another task for comp was to go through all the static DMP shots and add movement and life wherever plausible. This included the ocean waves crashing into the shore in the distance as well as adding in soldiers in the camp, and troops arriving from the beach, crew servicing the catapults, interactive light onto the camp tents, adding camp fires and tents to bring it all to life and give the sense that a huge army was gathering.

How did you create the various other environments?

Most of the environments were shot in Hungary and England. Environment work was making these feel like 15th Century France or London.

One of our plate extensions was the arrival of the English army for the siege of Harfleur. This establishing shot was a wide panoramic of a Hungarian landscape with hills and forests, and had to look like the French coast with a small village settlement, Harfleur castle on the hill and the English camp starting to take form. Most of the plate extension was done as a DMP by our environment artist Saphir Vendroux. We replaced the hills for the sea and coast line, added some fields and farms, and extended the on-set village. Saphir also set dressed the English camp to extend it, by using our CG assets for tents, props, campfires. We also added all the English ships in the bay from our armada assets, as well as the Harfleur castle. This shot alone represented almost all of our CG assets and FX work we had on the show in one place, and along with the beautiful plate photography, it became one of the team’s favourite shots in the film.

Another interesting plate extension was creating a view of London over the Thames in 1415. The plate was shot at Berkeley Castle which was standing in as Westminster Abbey. Our environment team, supervised by Jeremie Touzery, did some extensive research on how much of Westminster was built at this time as well as the rest of London. Luckily we managed to dig up some plans of the cathedral that would have actually been there at the time and no longer exists today. We modelled it in Zbrush to extend the castle from the plate. The background was done as a DMP, using as many references as we could find from this century for the look, and then we added CG boats on the Thames.

For the battle sequences, we had to augment the plates with CG trees to keep it closer to the real location in France. Our environment artist Simona Ceci was in charge of this sequence. She built out our trees as well as any smaller shrubs and ground at the edges blending into the practical battlefield and also added a wind motion to match whatever was happening in each plate. We also had to add in all of the mud, which was an important part of the story. On most of the shots the mud was done as DMP, and then in some of the closer shots we created CG mud with an FX pass to have a deformation wherever the CG characters were stepping and sliding into it.

How did you approach the Battle of Agincourt?

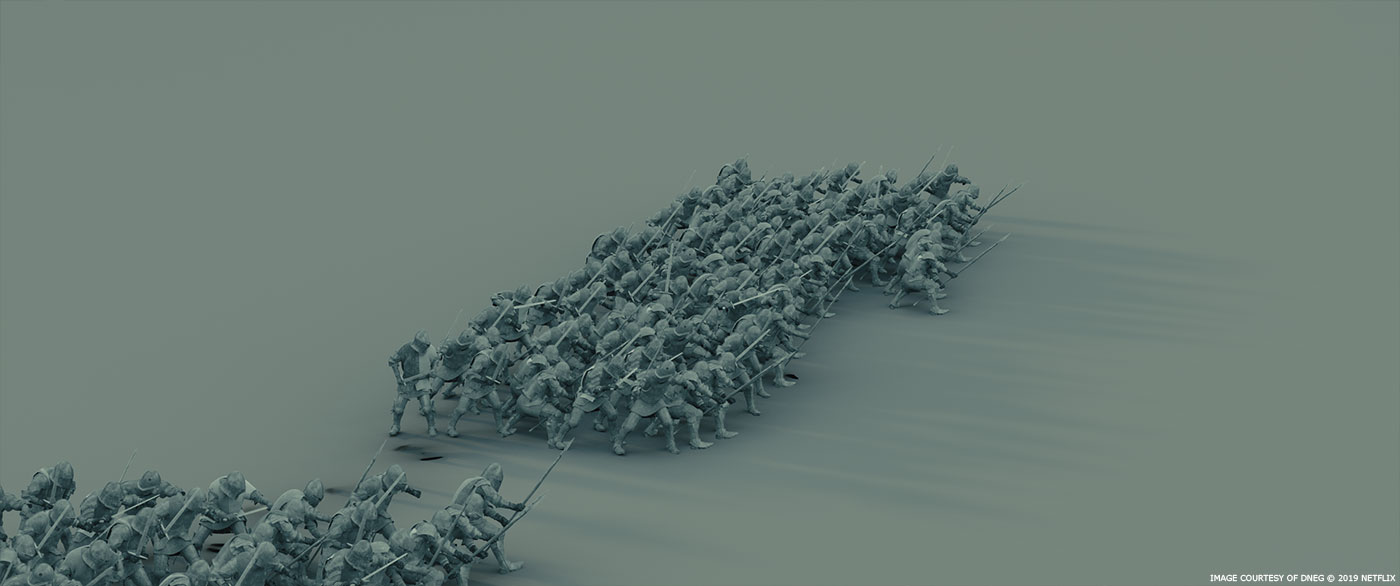

The key brief for this sequence was to show the huge scale of the French army and the apparent hopelessness of how outnumbered the English army was. A lot of our early sessions involved looking through the cut with our animation and comp teams and figuring out what we could do to add a sense of scale in almost every shot. We had our layout team block out passes of the entire battle, filling out the soldiers with CG troops to make sure that the units progressed through the space properly and we were presenting the correct sense of scale in continuity across the shots. It was then lots of back and forth between the edit to see how each shot was playing in the cut to ensure that everything felt right. Once we got into the more frenetic battle it was about finding spaces to fill out the plate photography wherever possible and looking at how we could add a sense of danger and violence into what had already been shot. We had quite a bit of freedom to build out the armies in whatever way felt appropriate to the story, so it was quite a bit of fun planning what would go into each shot. Lots of this work would also include falling horses, raining arrows, knights getting hit with arrows, falling and getting trampled etc.

How did you create and animate the armies?

Eric Bates was our animation supervisor and needed to get his team through a large volume of work in a short amount of time. We planned out an approach that started with an in-house Moven motion capture session that allowed us to block out a large number of shots in a short space of time. He quickly created a library of assets that we could then have the layout team dip into to dress out many of our larger crowd shots. His team then went back through and refined anything that was working well in shots by focusing the mo-cap clean up from the foreground backwards. There were then plenty of shots that featured foreground action that required bespoke hero animation.

We also created a library of vignettes that consisted of two or three soldiers fighting one another. Our layout team started by dressing these into most of the shots as a first pass. We would then identify areas that needed some bespoke animation or shot specific work. For the wider scenes the result felt fairly static and we wanted to create an overall larger sense of this mass moving against one another within the frame. Our FX team, led by Lisa Nolan, started with a scatter of some of our vignette library soldiers to create the volume of soldiers in the mosh pit. The animation team then went in and hand animated some key elements around this such as groups of horses circling around and back into the crowd, or soldiers parting ways as the horses entered to give the whole mass a sense of flow and avoid everything feeling locked in place. It was a combination of things working together to craft the final image. The comp team then went in and dressed the battlefield with some additional elements of soldiers or dead horses and then spent a lot of time bringing everything together into the final composite.

There is a long continuous shot when Henry V joins the battle. Can you explain in detail how you approached the work on it?

Due to the scale of this shot – and the fact that the team were already going full tilt on all the other shots – we made the decision to schedule this entire shot onto one of our comp leads, Rich Grande, so that it didn’t disrupt the rest of the schedule. He worked in isolation from the rest of the shots on the show and more or less single handedly put the entire shot together over the duration of the project. First he went through and made sure all of the transitions worked. They had rehearsed and shot the scene mostly as a single take, but preferred performances from different takes and also wanted to tighten some of the action up in the edit. This meant that there were some fairly natural transition points already, but Rich had to spend a fair bit of time trying to get that working seamlessly so we could get the timings locked down and signed off before we could involve other departments. It also allowed us to break the shot up into 7 sub shots to make it more manageable to work with and iterate. He blocked out a first pass using 2D elements just to give our layout team a sense of where we wanted things to be in each moment and also help get initial sign off on things with our director.

Once we showed this, it became clear that he wanted more scope to this shot than the elements alone would allow, so we had our layout team go in and dress out the mid-ground and background with our created animation library of CG soldier vignettes and horses as well as some shot specific animation for the foreground soldiers. We then needed to integrate the soldiers feet into the thick wet mud on the battlefield, and our FX team did some fantastic mud simulation to help get all of this working. It had to hold up pretty close to frame as it was mostly the foreground soldiers that were the problem. Some additional 2D elements were then used to dress out the deep background. This shot ran for the entire duration of the project, and we had a few curve balls to field close to the end of the show, but I’m really pleased with how it turned out.

Did you want to reveal any other invisible effects?

There are lots of invisible effects on this show. Most of the swords, poleaxes and daggers were CG for safety reasons. The arrows that littered the ground were all CG and there are quite a large number of shots where the soldiers and horses were fleshed out with additional CG ones, which I think is pretty seamless. Lots of the trees around the Agincourt battlefield were CG. Lots of bits of bendy armor and swords that needed fixing. There is a large top down shot where the French soldiers are crushing in on Falstaff and a number of the soldiers around him were all CG. They were wonderfully animated, lit and composited by our incredibly hard working and talented DNEG team in Mumbai, led by Kedar Khot (DFX supervisor), Hitesh Barot (Anim supervisor) and John Britto (Comp supervisor). It’s honestly seamless and you would have a hard time knowing the shot contained any CG at all. It is one of my favourite shots in the show because of the intricacy of the work involved. The whole project is one of those pieces of work where you hope almost everything can be considered invisible. If we have all done our job properly no one should even think we did any VFX.

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

There were several that had their fair share of challenges due to the scope of work and short schedule.

Is there anything specific that gave you some really short nights?

Not really. Once we had a solid plan in place in terms of methodology, things started to move at a good pace. There were a few spicy weeks towards the end of delivery but nothing terrible. Our comp teams generally get the brunt of things as they are at the end of the pipeline and scrambling until the 11th hour to get that final layer of polish on shots, but I think we managed to keep things under control for the most part of this show.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

I think it has to be the siege of the castles at Harfleur. The photography is stunning and there was some beautiful environment work created by our team, led by Jeremie Touzery, that sat seamlessly into the scene and added a wonderful amount of scale to army camps, ships and castles.

What is your best memory on this show?

Having a baby! I actually found out my wife was pregnant when I was on my last day of the shoot in Budapest and he was born towards the end of the post schedule so the whole project has amazing memories throughout for me. Work wise though it was seeing everything start to come together and fall into place on some of the bigger shots. Once we had figured out our methodology of how to get some of the large battle scenes working nicely, and we knew what would work, it was a great feeling and exciting to see it all build up in the shots.

How long did you work on this show?

From the very first meeting with Andrew and David to finishing delivery of the VFX came in at around a year for me, but just the post was around five or six months.

What’s the VFX shot count?

We completed around 276 shots in total.

What was the size of your team?

91 in Vancouver, 150 in Mumbai plus around another 50 people for roto and prep.

What is your next project?

I can’t go into specifics but its a project doing some photoreal creature work for a new content platform, which so far has been a really fun and unique experience. We have a great team here and the production side were all incredibly collaborative and understanding of the VFX process during the shoot and prep phase.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

ET, ALIEN, THE GOONIES and TERMINATOR 2.

The first three for narrative and storytelling, but T2 for where cinema was going digitally.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

DNEG: Dedicated page about THE KING on DNEG website.

Netflix: You can watch THE KING on Netflix now.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2019