In 2016, Pete Dionne explained to us the work of MPC on PASSENGERS. He then took care of the effects of A WRINKLE IN TIME.

How did you get involved on this show?

I was the MPC Supervisor for Rob Letterman’s last film, GOOSEBUMPS, with overall VFX supervisor Erik Nordby and VFX Producer Greg Baxter. We were deep in the trenches together on that one, which was also a CGI creature-heavy film, so it made sense to get the band back together for POKÉMON: DETECTIVE PIKACHU. It’s a gift to be able to start a project with such familiarity, trust, and with a working shorthand from the beginning.

How was the collaboration with director Rob Letterman?

I love working with Rob. He comes equipped with a clear vision, but also welcomes collaboration and outside ideas with open arms. I appreciate his instincts and sensibilities as a filmmaker, both cinematically, and his ability to weave humor, heart, and sincerity into his filmmaking.

What was his expectations and approach about the visual effects?

Rob’s goal was to have the audience connect with these Pokémon, and especially Pikachu, as realistic creatures, and never allowing the cartoon-ness of the character designs break the illusion. He looked to achieve this both in how the characters were developed, but also in their performance, and how they integrate into the world around them. Rob is quite a restrained director when it comes to VFX; he always begins with ‘what’s real’ as a base, and fully embraces the natural constraints which reality poses, rather than pushing effects too far into the realm of impossible or fantasy. I appreciate this about working with him, as it lines up with my own taste and instincts.

How does his experience in animation help him on this massive show?

Rob’s deep experience with both animation and visual effects certainly brought a lot of focus to his vision, and to the entire process in general. He knows exactly where to direct his attention, what to delegate, which high-value aspects to fight for, and which incidental aspects he probably shouldn’t let distract him. The CGI characters and VFX requirements for DETECTIVE PIKACHU were extremely demanding on Rob, but he built a great team around him, and navigated us all to a successful outcome. I specifically think his unwavering vision of the character designs and Pikachu’s performance was an absolute slam-dunk.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

MPC delivered around 850 shot for DETECTIVE PIKACHU, including designing 40 CG characters and building two massive CG environments, so there was quite a lot of work for us all to stay on top of. VFX producer Cecilia Marin and I, along with an amazing team of supervisors and production managers, continually managed how to best distribute the work across MPC’s global studios. The film was led from our Vancouver studio, with a significant amount of design, build, and shot work completed by our studios in Montreal, Bangalore, and London. MPC’s Los Angeles studio also heavily contributed to initial character design and conceptual development, as well as postvis. This project was a serious global effort, but we were fortunate to have quite a lot of experience spread across our creative, production, and support teams to handle the complexities, so generally it was a smooth experience.

How did you work with the art department about the design of Pikachu?

The initial development of the Pokémon characters began as concept artwork. Rob, Erik, and the folks at Legendary Pictures and The Pokémon Company iterated on these at the artwork stage until the concept designs were approved, at which point they were handed off to the character asset and animation teams for further development. However, Pikachu was the exception to this. We discovered that Pikachu’s visual design was too dependent on his personality and motion design to develop on it’s own, so we made the choice to create him as a rigged asset in CG from the ground up, taking more of an overall, holistic approach to his design process. This is generally a very slow and restrictive way to create CGI characters, but we stuck to a development path early on that allowed for a lot of exploration, testing, and broad-stroke development before the schedule required us to focus on any of the finer CG detailing. Looking back, it was the only way we could have realized Pikachu to this level.

Can you explain in detail about his creation?

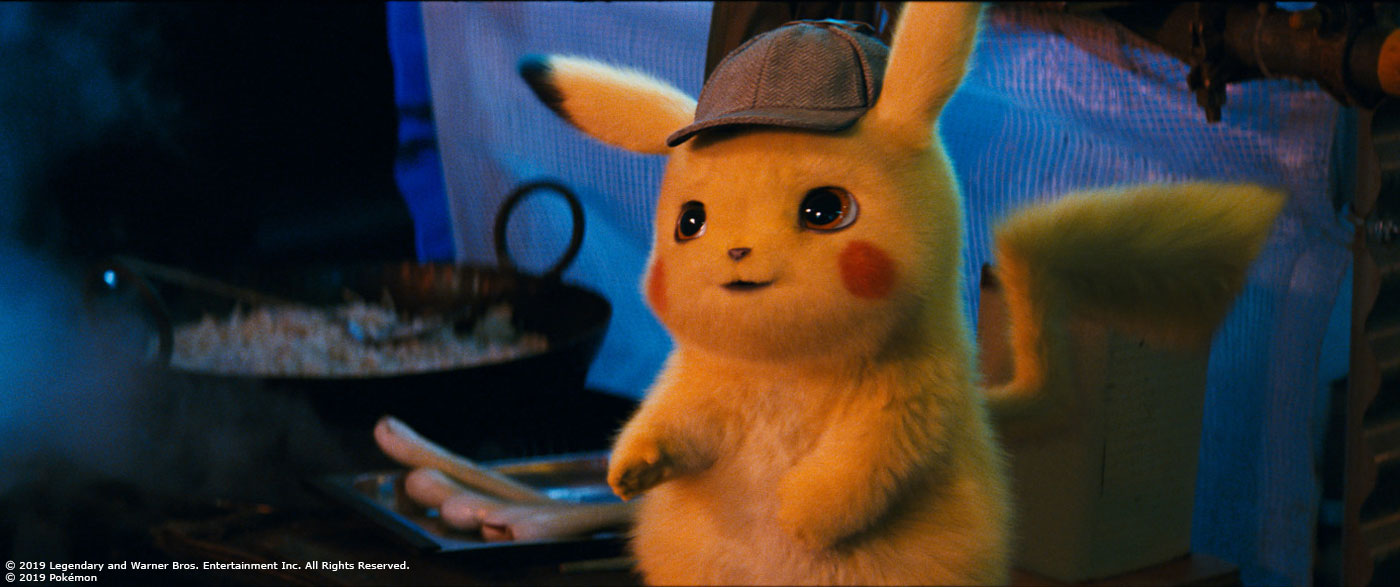

We knew from the start that we didn’t want to depart from the core design of Pikachu’s beloved 2D anime design, but how we interpreted this design as we brought him into the real world proved to be a very delicate and involved process for us. We began by creating a general 3D form that closely matched his iconic 2D silhouette and proportions, and then conformed an anatomically accurate quadruped skeletal and muscle system inside of him, similar to that of a rabbit. We made minor adjustments to his overall form along the way based on anatomical and rigging requirements, but we tried to never compromise the overall connection to his 2D design. We knew that visually, our Detective Pikachu character had to be as adorable as possible to fully sell the comedic juxtaposition of his crusty personality, so we were strategic in which cute animalistic features we embraced, and which unappealing ones we disregarded. For example, we referenced the cutest little kitten noses we could find for Pikachu, and evaluated hundreds of images of various animal paws until we ended up with adorable bunny paws to serve as inspiration for his feet. Features like weird inner-ear detailing and articulated teeth and gums, things that are impossible to make look appealing, we avoided or deemphasized as much as possible.

Can you tell us more about his animation and especially his face?

Rigging and animating Pikachu’s face was perhaps the most challenging task for us, because we were trying to juggle three targets at once; having it resemble 2D Pikachu, using Pikachu’s face as a vessel for Ryan’s comedic and dramatic performance, and having it maintain the feel of a physical animal rather than a CGI cartoon face. We began by building a facial rig for Pikachu that was based on a real-world feline muscle system, which is how we chose to specifically interpret his mouth, muzzle, and brow. For performance reasons, we pushed the range of motion of each muscle group further than that of a common cat, but by strictly following this feline anatomy, it provided us with a sense of realism as well as real-world anatomical reference to pivot from. We then captured a full FACs facial workout session with Ryan Reynolds, which was basically sticking a head-mounted camera on him and running him through every expression and mouth shape you can think of, around 80 in total. With this library of Ryan’s facial shapes, we then poured through hours of Pokémon anime movies and TV shows to curate an equivalent library of 2D Pikachu’s expressions, which were essentially variants of seven highly iconic and recognizable expressions. We then went shape-by-shape, pushing our feline facial rig to find the right balance between Ryan’s expressiveness and Pikachu’s Pikachu-ness. This process gave us a large library of highly nuanced facial expressions for Pikachu which we were very confident in, so when our animators sat down with Ryan’s performance capture video reference for each shot, they were able to quickly achieve an appealing and believable facial performance.

What kind of references and indications did you receive for his animation?

During preproduction, our Animation Supervisor Jason Fittipaldi prepared a vast reference library for all Pokémon characters. This included thousands of anime clips to keep us aware of the personality and motion design of each character, but also a huge library of the most relevant reference from the animal kingdom that he selected for each character. This reference really helped to keep our CGI animation grounded in reality and avoided anything too cartoony or freestyled, and is what really made many of these characters relatable. For example, when we were designing Bulbasaur, Jason found these adorable clips of frolicking bulldog puppies and whipped up a quick motion study by rotoscoping the puppies into a few Bulbasaurs. It made these weird looking creatures become instantly adorable, and that level of animalistic nuance in their performance made them feel completely believable.

Pikachu himself was based on a collection of several different quadruped animals, depending on on the actions performed. We found ourselves referencing bunnies, cats, and bush babies quite often when Pikachu was upright, and red pandas when he was down on all fours. We also referenced raccoons and marmots for Pikachu’s fat and skin simulations.

Can you explain in detail about the creation of his fur and eyes?

When we first added a layer of bright yellow fur overtop of Pikachu’s squishy round body, we were surprised by how much he looked like a child’s stuffed toy, rather than a real animal. In other aspects of Pikachu’s features, we took a very cautious and soft touch in adding real animal detailing, but for his fur, we found that we had to be heavy handed in our approach, and make the qualities and features of his fur as recognizable as real-world animal hair as possible. We focused on kittens and bunnies as our source of inspiration and reference, and we spent a lot of time carefully analyzing and discussing every aspect of their fur, and how to best apply these subtle details to Pikachu. In addition to carefully matching qualities the variation of density, stiffness, length, inclination, and flow patterns that naturally exists across a rabbit and cat’s body, we also looked to the animal kingdom for queues on how to pull off his vibrant yellow fur.

Pikachu’s eyes are most often represented as big black discs in the anime, but it was critical to have visible detailing within our Pikachu’s eyes to better read the depth of his emotion, as well as to help the audience track his eye-line. We found that as long as we maintained a giant black pupil, then sneaking in a thin brown iris, a thin moist meniscus, and a subtle hint of milky sclera in the corner of his eyes gave us the detail and anatomical complexity we needed, without compromising the connection to his anime design.

How did you handle the various interactions of Pikachu with the actors and the environments?

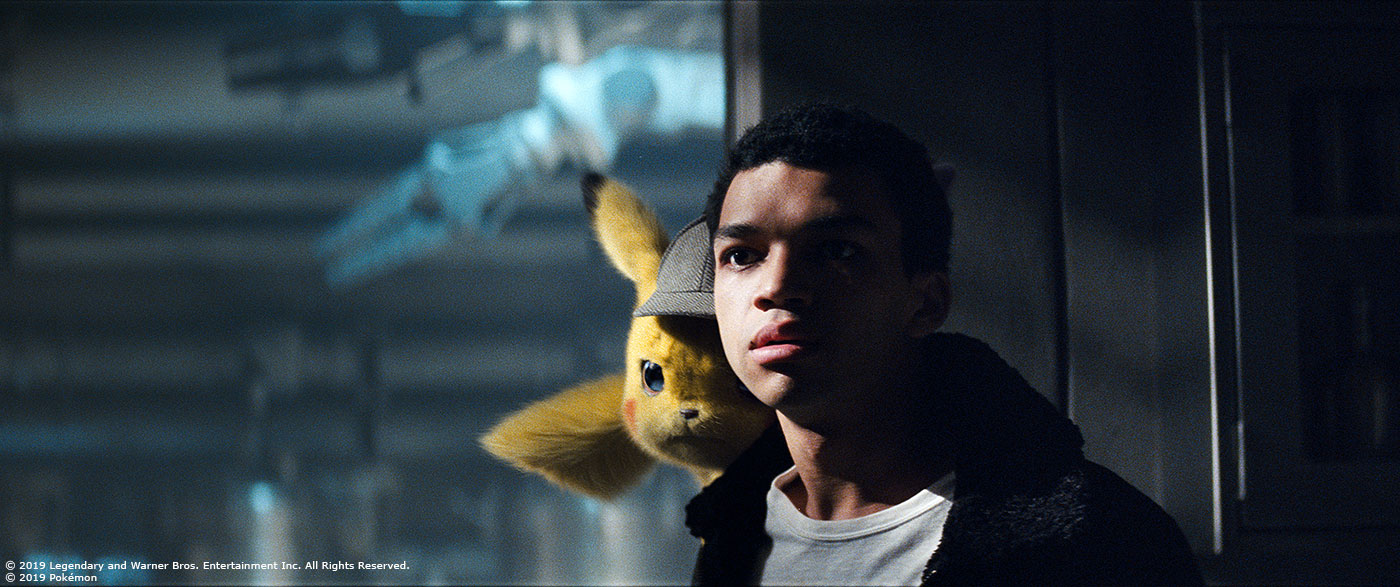

Having robust on-set reference for our Pokémon was critical, to help the actors and crew in their awareness of the intended performance and proximity of our CGI creatures, as well to shoot as reference for our VFX team back at MPC. During pre-production, Erik hired a studio called KM Effects to create practical puppets, stuffies, and ‘material spheres’ for the majority of our Pokémon. As we approved the CG surfacing for each character, they would create real-world equivalents of these materials and apply them to a sphere on the end of a pole, similar to the chrome and grey spheres which have been standard practice for years. For every shot, we would capture these skinned/furried/textured material reference spheres under set lighting conditions through the film cameras, to provide our lighters and compositors with explicit reference to match our CG Pokémon to.

For Pikachu specifically, we used a puppeteer with an articulated foam Pikachu on-set to drive all performance takes. This was gold for us in VFX, as it helped Rob block out Pikachu’s performance with the actors, it allowed our cinematographer John Mathieson to light the scene and make lens and camera choices with Pikachu in mind, and it gave the Editorial and VFX teams additional reference to work with in post-production. We would typically shoot the first few takes with the puppet in-camera, until everyone was comfortable with Pikachu’s performance and placement, then we would take him out and shoot remaining takes without the puppet in the shot. Once Rob had a few takes he was happy with, we then shot clean tiles of the set which were used to remove the puppet from the plates. Next, we would shoot our lighting references of the chrome, grey, and material spheres through the film cameras. Finally, we would shoot 360 degree bracketed HDRI still photography of the set from various locations, which we used to measure the exact placement, intensity, and color temperature for all of the set lighting, for us to recreate in CG.

Can you explain in detail about the iconic lighting used by Pikachu?

Both Pikachu and Mewtwo’s powers were developed to be referential to the stylized effects in the anime and video games, but recreated with real-world elements and physics in mind. For Pikachu’s powers featured in this film, specifically Volt Tackle, Thunderbolt, Iron Tail, Electro Ball, and general ‘charging up’ effects, we gathered dozens of anime and video game clips and broke down the key characteristics for each. We then gathered dozens of amazing clips of real-world elements, like electricity, plasma, vapour, and sparks, and used those as ingredients to recreate the anime effects. To create the glow that is often around Pikachu’s body in the anime when he’s using his powers, which may look cool but is not really photographic, we chose to represent this as an internal illumination from within, rather than an external illumination. Since we already had a CG representation of Pikachu’s internal anatomy modeled and rigged, we were able to drop light sources deep within his body, and allow the physical lighting and shading within RenderMan to provide us with some really cool and complex elements for our compositors to play with.

Beside Pikachu, which one was the most complicated to create and animate?

One of our most challenging Pokémon to create and animate was Mr. Mime, as he followed a different set of rules to the rest. As a humanoid character with bizarre proportions and a creepy face, he had the potential to become quite disturbing if we brought him to life as a human. But the interrogation scene was so hilarious that we knew that we had to find a way to make him appealing! We chose to go in the other direction as the other Pokémon and made Mr Mime feel as inorganic as possible, to swing him firmly into the other end of the ‘uncanny valley’ spectrum. We designed his torso and horns as squishy painted foam, with all of the weathering and cracking you would expect if you left your Nerf foam football outside through the winter. His red shoulder balls we designed as rubber kickballs, emphasizing the traditional hatched texturing that is common on the surface of these balls. We referenced thick latex for his face, with enough deep sub-surface scattering to make it clear that there is no flesh or organic structure below the surface. By recreating Mr Mime with all of these very familiar but non-organic materials, this allowed us to push him into a cartoonish realm, but yet still grounded in reality.

How did you create the various locations and especially Ryme City?

Since our digital Ryme City is featured so heavily and plays such an integral part of the film, we chose to design and build it as one epic monolithic environment, for consistency of look and layout. This covered us for various establishing shots from outside the city looking in, for our CG aerial battle between Pikachu and Mewtwo from within the downtown core, and for all of our street-level plate embellishment and replacement requirements throughout the film. The brief from Rob was to create a city that matched the lived-in grittiness of our London street photography, but with the towering density of Manhattan, and with the vibrant, dense signage of Tokyo. We began with the data capture for our main shooting location in London, which included shutting down Leadenhall Street for an entire day, and using a mix of street, rooftop, drone, and helicopter photography to capture this area at multiple altitudes. From this data, we rebuilt a five-block radius of our core to a very high resolution. To create the vertical density of Manhattan, we designed and built over one hundred towers, which we then dropped into our core and extended throughout our city. As Ryme City is established to be close to a mountainous region, we gathered high-resolution lidar data of Vancouver and the surrounding terrain, and used this as the base for our city beyond the downtown core. Finally, MPC designed and built hundreds of unique Pokémon-themed 3D signs of various scales and purposes, which we then scattered throughout the city following a real-world inspired logic. This full CG build took us over eight months to compete, but once it was done, we were able to drop it into hundreds of shots and quickly turn around a highly detailed and consistent city for every camera angle required. It was a menace to our renderfarm, but the results were fantastic.

Where was filmed the different locations?

The majority of this film was shot on location in London, as well as northern Scotland for the scenes when they are around the lab. The soundstage work was shot at Leavesden Studios and Shepperton Studios near London.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

I have too many! Tim’s first arrival to Ryme City is such a visually dense and breathtaking sequence. I think that the Mr Mime interrogation scene is hilarious. The final battle between Mewtwo and Pikachu looks great. From a pure VFX perspective my favorite is the Torterra Valley sequence, as the amount of CG in that sequence is staggering, and it was incredible to watch the team behind its execution drive it to completion.

What is your best memory on this show?

One of my favorite memories from this show was the day that the first DETECTIVE PIKACHU trailer dropped. I was so confident in our character designs and the overall look and tone of the film, but they were so radically different from what most people were expecting that I honestly had no clue how it was going to be received. I was pretty relieved when the internet blew up with such positive excitement, and that energy and anticipation really fuelled all of us the rest of the way to the finish line.

How long have you worked on this show?

I worked on DETECTIVE PIKACHU for close to two years. We were blessed to have such a long preproduction period for our character design and development, but it also made for quite a lengthy journey from start to finish!

What’s the VFX shots count?

MPC completed around 850 shots and around 40 characters.

What was the size of your team?

We had over 600 people throughout MPC contribute to this film.

What is your next project?

Getting some sleep!

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

MPC: Dedicated page about POKÉMON DETECTIVE PIKACHU on MPC website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2019