Trey Harrell began his career at Mr. X more than 8 years ago. He has worked on many projects such as TRON LEGACY, THE THREE MUSKETEERS, POMPEII and RESIDENT EVIL: THE FINAL CHAPTER. He talks to us today about his work on THE SHAPE OF WATER, his third show with director Guillermo del Toro.

What is your background?

I come from a background in the advertising world where I’d carved myself a niche by focusing on skills that were rare, or absent, in smaller markets at the time. Around eight years ago, I got the call to come up as a 3D Generalist to work on TRON: LEGACY at Mr. X in Toronto, where I’ve been since then, working on nearly 30 shows first as a Lighting & Lookdev TD then CG Supervisor, and now as a VFX Supervisor.

How was this new collaboration with director Guillermo del Toro?

Guillermo is one of my favorite filmmakers on Earth. I’d worked with him before indirectly on CRIMSON PEAK and MAMA and directly I served as CG Supervisor for two seasons of THE STRAIN.

It’s incredibly rare for directors to understand the craft and methodologies of VFX anywhere near as well as he does, and even more rare in that he participates in desk-side and dailies reviews with individual artists quite often.

He’s got an infectious energy that pushes everyone to give their best and he wears his heart on his sleeve. We’re really fortunate that he lives nearby in Toronto and is eager to drop by and jam with the artists at a moment’s notice.

THE SHAPE OF WATER was a bit of a departure from other projects I’d worked on with him — any projects I’d ever worked on, really — it’s at heart a musical, but contains elements of a multitude of genres all in perfect balance. It’s a tonal tightrope that was daunting to say the least. I can’t imagine another director who’d be able to pull it off.

What was his approach and expectations about the visual effects?

Guillermo developed The Amphibian Man creature over the span of close to four years, with Mike Hill, Shane Mahan and the team at Legacy Effects.

From the beginning, it was clear that the creature’s eyes and face would need to be digitally enhanced — the division of labor between the practical and digital disciplines was established early on in preproduction as a “best of both worlds” approach.

In general, Guillermo wants to get as much as possible in-camera and he wants his creatures physically present on-set so the actors have another actor to perform against. It’s rare for him to use any green screen at all. Tracking markers will only go up in the rare event that he’s planning on replacing something entirely in CG — I can count four shots off the top of my head on Water where we had them.

How did you organize the work with VFX Supervisor Dennis Berardi and inside Mr. X?

Dennis Berardi was the overall VFX Supervisor on the show, overseeing the on-set work as well as completed shots when they went out the door during postproduction.

As Digital Effects Supervisor, I served as a hybrid between VFX and CG Supervisor — during preproduction tests and principal photography, I’d establish methodologies and shot approaches, develop the Amphibian Man asset and rigs and make sure the pipeline was ready for our first round of proper turnovers. I’d also handle VFX Supervisor duties in-studio when Dennis was on-set or unavailable.

Guillermo edits as he shoots — the pipeline had to be ready to start making shots on day one of principal photography.

Can you tell us more about your work during the preproduction and the previsualization process?

During preproduction, our creature artists did numerous animated ZBrush sketches, allowing Guillermo to sign off on things like how the creature would blink and how he would eat or hyperextend his jaw – mechanical issues that not only would affect things like topology and rigging downstream, but also how del Toro would approach filming certain scenes.

We also used the preproduction period to film under water reference and run tests on the dry-for-wet filming methodologies.

The movie opens with a beautiful continuous shot underwater. Can you explain in detail about his creation?

The opening shot is over 3,000 frames long and begins in an entirely digital river bed environment. The camera enters a cave, which is revealed to be the hallway leading to our heroine, Elisa’s apartment. From here we hand off to a practical plate filmed with classical dry-for-wet techniques, add multiple layers of underwater bubbles, sea life, particulate and floating props. The shot ends with Elisa gently waking from her dreams of being under water.

In addition to props, volume fog, and particulate and extensive rig removal, we also replaced Elisa’s hair and nightgown to complete the illusion of being under water.

Every blade of grass, fish and prop was timed along with the score of the film — THE SHAPE OF WATER is at heart a musical, set in a heightened reality — and we return to Elisa’s fantasy world several times during the film. It was crucial to establish the tone and aesthetic immediately in the opening shot.

Can you tell us more about the water simulations?

We had two major types of water work on the show. The first being the dry-for-wet aesthetic, selling the illusion of being under water in an abstract dreamscape. This methodology was echoed at the beginning and end of the film, as well as scenes in the OCCAM Lab where the creature is upright in his pressurized tank.

The dry-for-wet work consisted of volumetric lighting, deep holdouts, bubbles, particulate and blood per shot and was comprised of many layers of effects to complete the look.

In addition to the dry-for-wet segments, any time the audience sees the surface of the water, we relied on Houdini’s FLIP solver for extremely high resolution fluid simulations. In the sequence where the creature is introduced when his tank is wheeled in, the sloshing water was driven by our animated creature performance, and in turn drove sims for particulate, algae, foam and condensation on the glass.

We developed a custom path tracer and Cryptomatte extensions within our custom Houdini/Mantra-based lighting pipeline for the show that allowed for fine compositing control through arbitrary layers of refraction such as glass, condensation, water and volumetric effects. We also extended our Amphibian Man-specific SSS model to allow for per-light extraction via primary rays at those same transmission depths.

The movie takes place in the city of Baltimore. Which references and indications did you receive from Guillermo del Toro for the city?

Guillermo and the art department provided a massive amount of reference for specific buildings, signage and period advertising that we combined with our own reference to create look bibles for different areas of the city.

Can you explain in details about the design and the creation of the city?

Our Baltimore environment encompassed four primary locations:

The first was the exterior of Elisa’s apartment above the Orpheum Theatre including signage and the streetscape leading to the burning chocolate factory which included digital crowds and period vehicles.

Secondly was the downtown area of Baltimore, where the Lakeview Diner in Toronto was transformed into Dixie Doug’s pie shop.

Third was the canal environment where we had to replace the Toronto skyline and most of the environment – retaining only the extreme foreground and upper portions of practical barges.

Finally, we did an extensive amount of dressing in of period billboards on the highways during driving sequences.

We would ingest lidar or photogrammetry-based point clouds of the practical shooting locations and establish our master layouts before camera tracking began. Buildings and vehicles near to camera were modeled as extremely hero facades and interiors, brick-by-brick, whereas deep background buildings were dressed from a kit we’d developed during preproduction based on specific buildings Guillermo favored from our look bibles, For Water, we rolled our matte painting team and concept artists into an environments-specific crew with modelers, look development artists and lighters.

Our environments team was also responsible for developing a huge amount of period signage – establishing the tone and heightened reality of this show was extremely important and also a ton of fun.

We have everything from ads for Mexican TV dinners to whiskey billboards to Baltimore-favorite Old Bay Seasoning, complete with a blue crab in a top hat. Blink and you’ll miss them.

Small details like those are part of what Guillermo refers to as “eye protein” — layers upon layers of background detail that reward repeat viewings.

Let’s talk about the Amphibian Man. How did you work with the team of Legacy Effects for the suit?

Mr. X was brought in early at the script stage while the team at Legacy was still at work finalizing the creature’s design. Guillermo knew that the project was going to be limited in budget, and locked down very early in preproduction which portions of the creature would be practical vs. digital.

Over the duration of the project, Legacy built and maintained four versions of the suit and prosthetics, which Mr. X scanned on location with actor Doug Jones in suit at various stages of production.

Mike Hill and Shane Mahan from Legacy would also drop by the Mr. X studio periodically to offer assistance and insight with the digital version of the creature.

From the ground up, this was a highly collaborative effort between the acting, practical and digital visual effects disciplines, and parallels how Guillermo del Toro approaches his creatures in every other film.

Can you explain in detail about the creation of the Amphibian Man?

Working from scans of Doug in various versions of the suit, Mr. X set about creating an idealized version of the Amphibian Man. We decided early on to use Doug Jones’ own face as the template for the range of motion for the creature, where wrinkles would occur and so on.

We scanned Doug dozens of times out of suit to build a library of FACS-based shapes for our facial rig. Artists would sculpt poses for the creature mirroring Doug’s face and personality.

Later in the pipeline, animators and the director could compare our hand-animated performances on our digital Doug Jones facial rig side-by-side with the Amphibian Man rig. This was crucial in keeping his range of motion grounded and plausible.

Can you tell us more about the shader and texture work?

The shader work for the creature was a custom SSS model developed specifically for this show. Our goal wasn’t to realistically render leather or scales — we had to match the look and feel of a foam latex and silicone suit prosthetic appliance as well as very specific properties of the creature’s practical eye design such as lighting angles that would create a sort of “cat eye” glint effect.

I’m a firm believer that there’s an inherent charm in practical makeup effects that audiences accept and suspend disbelief much more quickly than entirely CG solutions. We spent an enormous amount of energy in disguising the seams between the practical and digital portions of the creature differently in each shot. We didn’t want the audience to know where to look for the seams as that can spoil the illusion.

In addition to our fully CG renders from our Houdini-based lighting pipeline, we also utilized a fairly old-school trick at the compositing stage.

In the early days of “talking animal” CG, it was common to project the practical photography on a tracked version of the animal’s muzzle, then deform the plate projection with the animated performance.

We used an update of that technique – entirely at compositing time in Nuke in our case – to help blend our seams between the practical and digital portions of the creature. It also allowed compositors to paint shot-specific blend mattes that were deformed along with the creature’s performance and extract fine details from the original photography such as water droplets.

In every shot in the film featuring the Amphibian Man, some level of animated performance was added, most commonly for his eyes and face.

Later we discover a beautiful bioluminescent effect on the Amphibian Man. How did you create it?

Shane Mahan and the team at Legacy developed some UV-sensitive paints for the creature, drawing inspiration from animals with bioluminescent qualities such as cuttlefish, glow worms and a type of squid prevalent in Toyama Bay in Japan. Screen tests were performed under a practical black light, but ultimately the effect was realized digitally because it allowed for greater flexibility.

Mr. X used a combination of optical flow tracking techniques on the creature’s stripes along with full body and facial tracks. We could either pipe an animated UDIM-based texture sequence through the Amphibian Man’s body track, or use 2D tracks and roto along with a robust custom Nuke toolset we developed to generate the depth of the effect and animation sequencing.

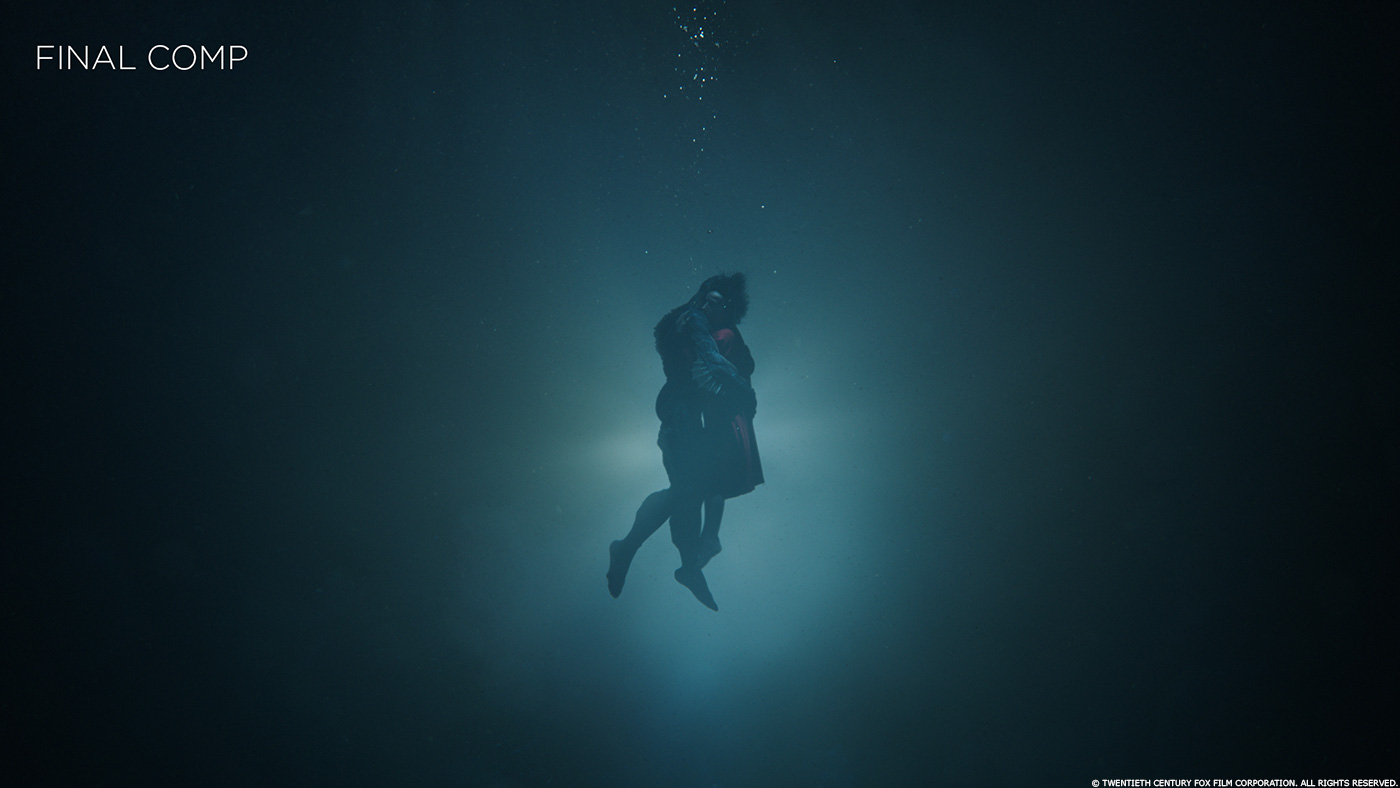

The movie ends with a beautiful picture of the Amphibian Man and Elisa in the water. Can you explain in detail about the creation of this sequence?

This sequence was filmed practically using dry-for-wet techniques. A soundstage was flooded with smoke and the actors were suspended on wires with wind blowing and filmed at high speed.

The creature is entirely CG when swimming — that range of motion couldn’t be achieved practically. Elisa’s hair was pinned back on-set and replaced with a very carefully directed sim. Along with dozens of layers of particulate, bubbles and volumetrics and a digital gill prosthetic for Elisa, we help complete the illusion that they’re under water.

Is there any other invisible effect you want to reveal to us?

The damage to Strickland’s Cadillac was entirely digital — including the rain pouring over the hood and destroyed fender later in the film — inches from camera.

Which sequence or shot was the most complicated to create and why?

The opening and closing segments of the film were the most difficult by far. Not only were the shots extremely long on average but hundreds of different elements had to move in time with the score while we established the tone and aesthetic of the piece.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

After Elisa rescues the creature, she brings him to her apartment. He begins suffocating in her bath tub until she’s able to add enough salt to allow him to breathe. We cut back and forth several times between mostly practical and entirely digital versions of the creature, bath tub and algae as he pulls water in and out of his gills.

What was the main challenge on this film and how did you achieve it?

Our biggest overall challenge was in never affecting the audience’s suspension of disbelief when they’re looking at the creature. He’s our leading man and has an incredible range of emotion to convey non-verbally. The audience needs to fall in love with him alongside Elisa.

What is your best memory on this film?

I’ll give two — I love every chance I get to work with Doug Jones. He’s simply the best in the world at this type of creature performance in addition to being an amazing actor in general. He’s the sweetest guy you’re ever likely to meet and deserves sainthood for his dedication to the craft and hours in the makeup chair every single day. Watching him work is inspirational for me.

The second is seeing the premiere at TIFF with the cast inside the Elgin Theatre where portions of the film were shot. It was a magical moment when the audience realized where they were.

How long did you work on this film?

I personally worked on the film for just under a year total. We had a fairly modest budget for the show, but we did have the luxury of time to get everything just right.

Every single penny ended up on screen and we’re really proud of that.

What is the VFX shots count?

We ended up with nearly 600 shots — many of them quite long — accounting for an hour of the finished film.

What was the size of your on-set team?

Speaking solely for Mr. X, our on-set team varied between five and maybe a dozen people on a given day. Our DSLR-based scanning rig and team were out on-set during the peak periods, scanning all of the main characters and dozens of extras. Because Water was filmed in Toronto near our office, it was a luxury for our lead artists to be able to come to set and survey things like Elisa’s apartment and the creature themselves.

Seeing the insane level of care and detail put into the sets and costumes first-hand was incredibly inspirational to our artists.

What is your next project?

I’m currently in prep for Ad Astra.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

I’m going to skip the obvious ones — at this point we can all take THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK and BLADE RUNNER for granted, I think.

IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE might be the single most beautiful thing ever committed to film. If you have any interest in cinematography, composition, costuming and art direction or lighting design, it’s a masterclass.

Cinematic dystopias have always fascinated me — METROPOLIS (the silent Fritz Lang version) and BRAZIL are great touchstones among many, many others. I prefer my humor pitch black, and Terry Gilliam is a master – he’s also got an incredibly unique voice and eye.

Finally I’m going to throw in some non-specific campy fun. TERROR OF MECHAGODZILLA was one of those movies I caught on a random Sunday afternoon as a kid. To this day, I’ve got a giant soft spot for monster movies in general – but anything with man-in-suit versions of Godzilla, King Ghidorah and Mechagodzilla are at the top of that particular guilty pleasure list.

It occurred to me around the age of six or seven that people made a living playing with monsters because of films like this.

For my young mind, that seemed like a reasonable life goal.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Mr. X: Dedicated page about THE SHAPE OF WATER on Mr. X website.

THE SHAPE OF WATER – VFX BREAKDOWN – Mr. X

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2018

So much 60’s authenticity, but, when I saw the nighttime final plates, especially the one with the bus on the highway, the lighting is sodium vapor rather than mercury vapor. All public lighting then was blue mercury vapor lamps. Orange sodium vapor started in the 80s and was not really widespread till well into the 90’s and you can still see mercury vapor lights around. Some communities only replaced the old mercury vapor lights with sodium after they burned out, leaving towns with a psychedelic mix of both and in case nobody ever explained the color wheel to municipalities orange and blue are complementary colors, and orange/blue is probably the worst of them.