After working on THE MATRIX at the R&D department at Animal Logic, Andrew Chapman moved to London and joined the team of Framestore where he worked on TROY and CHARLIE AND THE CHOCOLATE FACTORY then he worked at Double Negative on films such as HOT FUZZ or HELLBOY II: THE GOLDEN ARMY. He then returned in Animal Logic for SUCKER PUNCH and work at ILM for PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: ON STRANGER TIDES and TRANSFORMERS: DARK OF THE MOON. He then joined Image Engine to work on ELYSIUM.

What is your background?

I came into VFX through a computing science background, my first job was in the R&D department of Animal Logic in Sydney during the original MATRIX. I then ‘crossed the floor’ to the production side and went to London. I was lucky to arrive just as the industry was blossoming there, working initially as a TD at Framestore and eventually a Digital Supervisor for Double Negative. I’ve since been back to Animal Logic, ILM, and now at Image Engine in Vancouver as a Visual Effects Supervisor.

How many shots have you done?

Just under 1000 shots were taken to final for the production, around 70% were created in-house at Image Engine.

What was the size of your team?

I was responsible for the Image Engine team – which was around 102 people at our peak. I was working under the overall Visual Effects Supervisor Peter Muyzers.

Can you describe one of your typical days on-set and then during post?

Working on set and during post are very different, and I love them both for different reasons.

On set is a great experience, being in the middle of this whirlwind of excitement, expensive camera gear, famous faces and explosions, but usually by the end of the shoot I’m itching to get back to the studio and dig into the work.??A typical day at Image Engine would involve a good mix of walking the floor, checking in with the artists on the hot shots and issues we’re trying to get through, some meetings, and a large dose of review time, either at my own workstation or dailies sessions in our nice new 4k theatre with Peter Muyzers. Unlike the on-set side of the job it can be high intensity the whole day, particularly toward the end of production when as a supervisor your time becomes a bottleneck for the entire crew, so there’s a lot of pressure to get everyone the feedback and answers they need to stay productive.

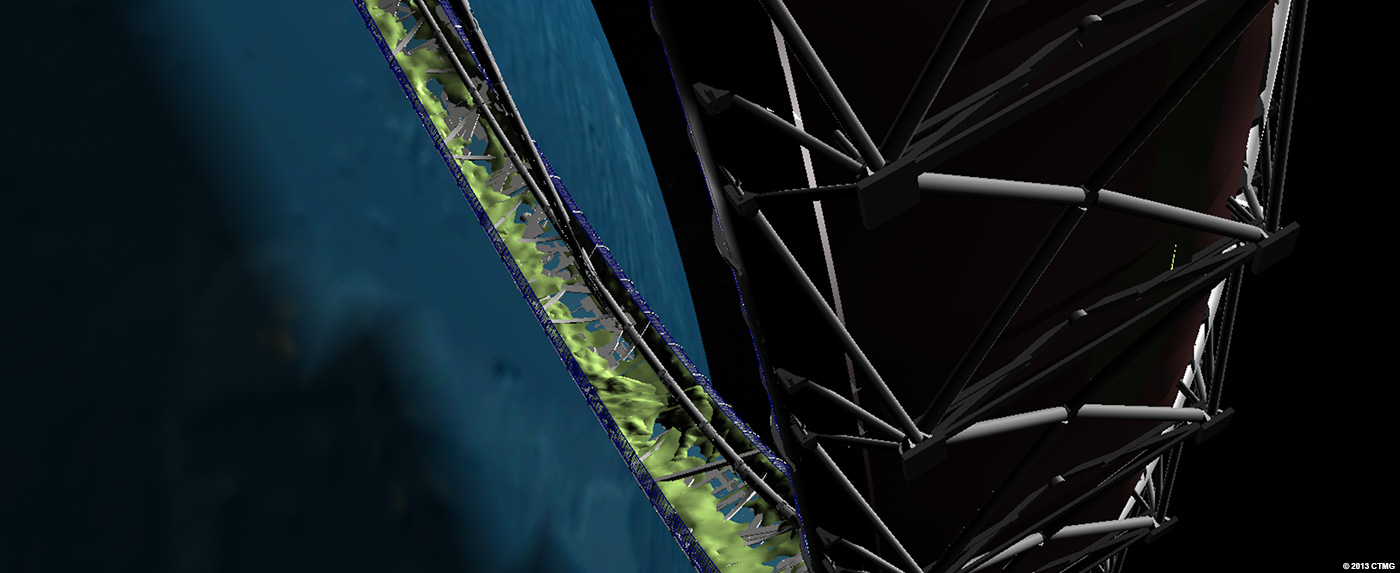

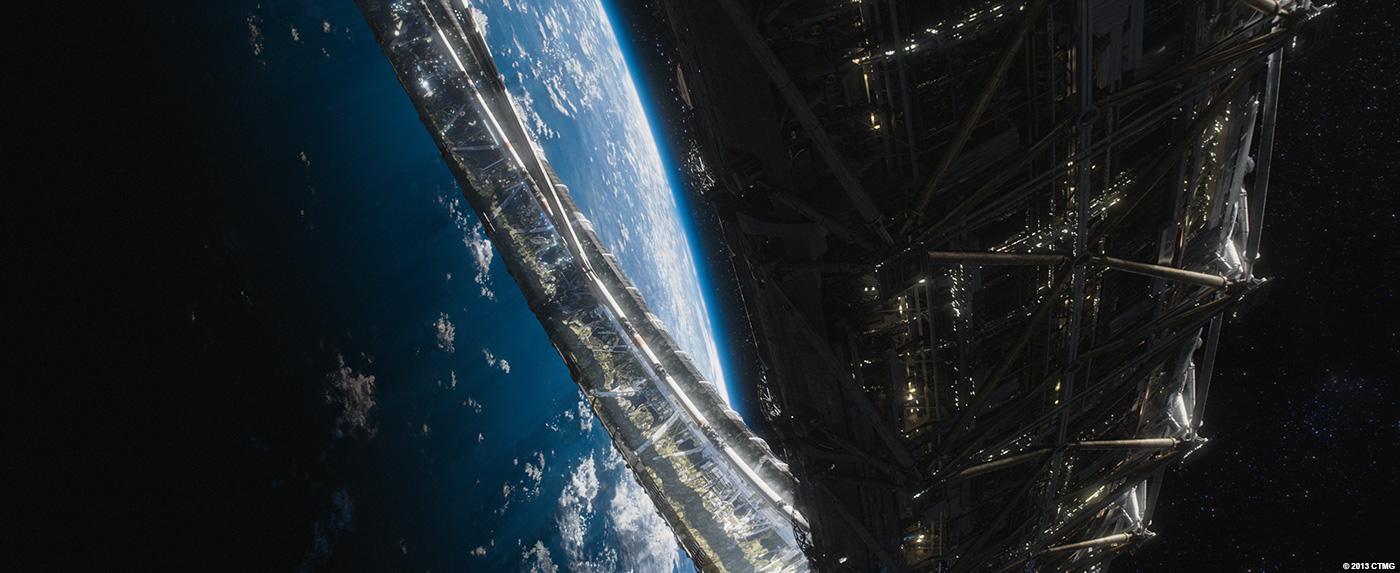

The Elysium station is really impressive. Can you explain in detail about its design and creation? & what were the main challenges?

The design of the Ring was realized by an in-house art department at Image Engine, inspired by drawings by Syd Mead. Peter Muyzers supervised a team of concept designers here: Kent Matheson, Ravi Bansal, Mitchell Stuart, and Ron Turner. They started with the broad strokes like the size of the ring (dictated by population density, mansion acreage and apparent size in the earth sky) through considerations like how many spokes it should have, the location of various utility structures, the layout of the terrain and finally down to the placement of each and every house, tree, pool and cabana.?Neill had a very specific look and feel he was aiming for with the interior living surface of the ring, it had to resemble Beverly Hills and the Hollywood hills, transplanted to the ring to become the ultimate gated community.

There were some broad challenges in achieving this, such as how to reproduce the feeling of that large hilly terrain within the constraints of a ring only 2 kilometres wide, and how to treat the atmosphere, which unlike earth is a narrow band bending in on itself rather than curving away to a vanishing horizon. We had to step a fine line with the lighting and atmosphere, which in theory would have the sky showing the black of space, but we needed to match in with the principal photography and keep that familiarity to portray it as a pleasant place to live rather than a space station.

Once Image Engine was through the broad strokes design effort we began our collaboration with Whiskytree in San Rafael. Whiskytree did an incredible job creating the terrain, they went to town on all that incredible inner surface detail which we then picked up as layers to include alongside the Image Engine elements of the hard-surface structure, flying ships, and effects layers in our final comps of the ring.

The movie features many set extensions. How did you manage this aspect?

There’s possibly less than you might imagine! The future dystopia of earth was shot in the favelas and a giant landfill site on the outskirts of Mexico City. It was a pretty nasty location but resulted in some great looking imagery. We did end up dressing up those earth locations with things like smoke plumes and adding in the future Los Angeles skyline.

Other set extension work was things like the Armadyne Factory, the Elysium Deportation Hangar and the Gantry sequence. The general approach for all this digital matte painting work was to build it out as rough geometry first so we have the real geometry for perspective and lighting, then to project matte painted elements on to that for expediency. It’s rare these days to be able to get away with pure matte painting for set extensions, it tends to be very much a 2.5D or full 3D approach now.

Can you explain in detail about animating the droids?

(Note: For this question, Earl Fast, Senior Animator at Image Engine is providing the answer) :

The first pass animation (often called animation blocking) went very fast for the droid shots, our mandate was to match the greysuit (droid stand-in) actors performance as close as possible head turns, weight shifts, foot falls and all the subtleties that the actors performed on the day of shooting took out all the guess work when it came to breathing life into our CG assets. Knowing and following the directed performances allowed us to get to the 80% mark very quickly.

From this point on we were able to concentrate on all the fine details of both the performance and technical challenges of the droids themselves. Plainly put we were replacing organic actors with mechanical hard surface droids and even though each actor had a uniquely scaled and proportioned droid built to match their bodies, varying levels of interpretation were often required. As a highly detailed mechanical asset the droids had imbedded limitations. For example the droid spine and neck had range of motion limits, a human spine bends and flexes throughout its length however the droid has specific hinges and sockets that provided mobility so each animator had to make subtle adjustments to the entire droid rig in order to create a performance that visually captured the essence of the filmed performance.

Animators were also tasked with trying to cover up as much of the original greysuit actor as possible in order to minimize the amount of paint work that would be required to ‘remove’ the greysuit actor from the scene. This would also require some interpretive work making small adjustments to many body parts to achieve maximum coverage with minimal impact to performance.

As a final design element the droids were equipped with several ‘gadgets’ that could be exposed and occasionally used by the droids. Things like cameras, scanners, lights, and weapons were added, we would often give the director several different versions of these gadgets extending, retracting, and reacting to their environment. Once the behavior of these gadgets was established we had to pay close attention to continuity but the result was quite cool and works well to ground the droids as mechanical task oriented machines.

How did you manage their presence on-set?

We had stunt performers in greysuits for every droid shot, which gave the camera crew something to line up on and Neill something to edit with, as well as being the perfect performance and lighting reference for us later on in VFX. Neill could direct them to get the exact performance he wanted on set, which meant we could match animate our droids to them as the first pass and know that would get us most of the way there.

We ran witness cameras in addition to the main film camera to give the animators an extra perspective on the action and depth of those performances, and captured HDRI images of each lighting setup featuring droids so that we could perfectly match the on-set lighting in the CG scenes.

How did you handle the lighting aspect?

(Note: This is best described by Image Engine Lighting Lead Rob Bourgeault) :

Our fundamental approach to the droids was really no different than how we light all of our assets. The real challenge was how to automate the process so we could light the shots efficiently given the time constraints, as well as maintain consistency in the overall look given that the shots were shared by multiple artists.

The look development of the droids was performed by the Assets Department. There were six droid types in total and all droids were shaded and textured in standardized environments so that they would respond to lighting in a similar way. There were over one hundred shots containing droids in multiple environments. Some of the smaller sequences of shots were performed by one or two artists in order to maintain lighting consistency. The larger sequences, particularly the droid battle sequence, required a more automated approach to lighting scene setup due to the number of shots and artists involved to complete the work.

As Andrew mentions, HDRI serves as the basis for determining the correct lighting environment for all of our assets. With respect to the droids, one of our primary objectives was to ensure that there was a realistic and believable interaction with both the live action and immediate environment. Based on the complexity of each environment and specific shot, the lighting department would analyze each background plate and associated HDRI in order to determine the elements necessary to complete this goal. The HDRI would then be color graded to match the plate or sequence. Having a practical model of the droid present during some of the filming allowed the lighting department to do some initial balancing of the droid asset shading and lighting prior to propagating the shots to multiple artists. Our lighting workflow facilitated the ability to render the asset into Nuke over the background plate, make quick adjustments to the material look of the droid through the use of different mattes, and then push the values back to the shader. Depending on render farm resources, we would sometimes provide adjustment nodes to the compositing department to assist with the final balancing of the droid asset. The material quality of the droid was highly reflective which was advantageous in having the asset more visibly interact with its environment. Multiple reflection cards were used to enhance the droids interaction with close proximity elements.

For those shots requiring interaction with live action actors we would request matchmove on a digital double that was then shaded to approximately match the general look of the actor. This digital double would be rendered with primary visibility off, however still contributing to the reflection, ambient occlusion, and raytraced shadows of the droid beauty render. In the case of the droid battle sequence, many of the shots were centered around a truck element which required heavy interaction with the droid asset. This required the creation of a specific asset that would be shared across all the associated shots which included a PTC file for indirect diffuse, reflection cards, ambient occlusion, and raytraced shadows on to the droid. This asset would also output passes that included cast shadows and reflections of the droid on to the truck surface which would then be used by the compositing department. Additionally, a PTC file was generated for the droid itself to contribute self reflection and indirect diffuse to the final beauty render.

Having established a lighting setup, the lighting department then had to devise a way to automate the process so that multiple artists could inherit the sequence based lighting scene with minimal setup time and technical complications. Senior Lighting TD, Edmond Engelbrecht, created a script that would import and reference the required elements including camera, assets, lighting rig components, and render passes. This allowed lighting artists to build lighting scenes quickly for their shots and focus more on aesthetic aspects of lighting and render management.

Can you tell us more about the work reviews?

Neill would come in a couple of times a week to review with Peter in our 4K theatre. It was incredibly helpful to have him close by and so accessible, it meant our turnaround time and feedback loop was reduced, increasing the efficiency for everyone. This was one of the reasons we could get through all the work in the film as a mid-sized facility.

In between the reviews with Neill, Peter and I would have dailies in the theatre with the crew, which stretched to a few hours per day toward the end of production as there was so much to review. The supervisors and leads would also do less formal reviews at their own workstations or at the artists desks, as it is imperative to avoid keeping the artists waiting on feedback.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

The design of the ring was certainly our biggest challenge, followed by the construction of the ring! If you imagine building the Elysium ring for real you would have teams of hundreds of architects, engineers and city planners designing full time for years, there’s so many details to be worked out.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

For me it was the epic shots of the Elysium ring. Creating all-CG shots of a fantastical environment is enough of a challenge in itself, but it would only work for Neill if it invoked a very specific flavor and likeness to the locations on earth we were attempting to echo. On top of that the collaboration with Whiskytree meant that there was a lot of complexity and data to manage between the two facilities and keep in sync if the two sets of renders were to mesh together as a cohesive final image. I’m very proud of the team for being able to pull it off, and I can now sleep soundly again!

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

Hmm… I’d have to be very predictable and start with BLADE RUNNER, I love science fiction and particularly anything that so completely immerses you in a future believable world. Others would be LOST IN TRANSLATION, THE THIN RED LINE and AMERICAN BEAUTY. This might seem like a bit of a random collection, but I appreciate real films that are truly about something and make you think about how you’re choosing to live your life. It bugs me how much money is spent making flashy films and sequels when there are so many great scripts floating around just begging to be made.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Image Engine: Official website of Image Engine.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2013